| Narcissus Temporal range: Late Oligocene – Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Narcissus poeticus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Order: | Asparagales |

| Family: | Amaryllidaceae |

| Subfamily: | Amaryllidoideae |

| Tribe: | Narcisseae |

| Genus: | Narcissus L.[1] |

| Type species | |

| Narcissus poeticus | |

| Subgenera | |

| Floral formula | |

| Br ✶ ☿ P3+3+Corona A3+3 G(3)

Bracteate, Actinomorphic, Bisexual Perianth: 6 tepals in 2 whorls of 3 Stamens: 2 whorls of 3 Ovary: Superior – 3 fused carpels |

Narcissus is a genus of predominantly spring flowering perennial plants of the amaryllis family, Amaryllidaceae. Various common names including daffodil,[Note 1] narcissus and jonquil, are used to describe all or some members of the genus. Narcissus has conspicuous flowers with six petal-like tepals surmounted by a cup- or trumpet-shaped corona. The flowers are generally white and yellow (also orange or pink in garden varieties), with either uniform or contrasting coloured tepals and corona.

Narcissus were well known in ancient civilisation, both medicinally and botanically, but were formally described by Linnaeus in his Species Plantarum (1753). The genus is generally considered to have about ten sections with approximately 36 species. The number of species has varied, depending on how they are classified, due to similarity between species and hybridisation. The genus arose some time in the Late Oligocene to Early Miocene epochs, in the Iberian peninsula and adjacent areas of southwest Europe. The exact origin of the name Narcissus is unknown, but it is often linked to a Greek word (ancient Greek ναρκῶ narkō, "to make numb") and the myth of the youth of that name who fell in love with his own reflection. The English word "daffodil" appears to be derived from "asphodel", with which it was commonly compared.

The species are native to meadows and woods in southern Europe and North Africa with a centre of diversity in the Western Mediterranean, particularly the Iberian peninsula. Both wild and cultivated plants have naturalised widely, and were introduced into the Far East prior to the tenth century. Narcissi tend to be long-lived bulbs, which propagate by division, but are also insect-pollinated. Known pests, diseases and disorders include viruses, fungi, the larvae of flies, mites and nematodes. Some Narcissus species have become extinct, while others are threatened by increasing urbanisation and tourism.

Historical accounts suggest narcissi have been cultivated from the earliest times, but became increasingly popular in Europe after the 16th century and by the late 19th century were an important commercial crop centred primarily in the Netherlands. Today narcissi are popular as cut flowers and as ornamental plants in private and public gardens. The long history of breeding has resulted in thousands of different cultivars. For horticultural purposes, narcissi are classified into divisions, covering a wide range of shapes and colours. Like other members of their family, narcissi produce a number of different alkaloids, which provide some protection for the plant, but may be poisonous if accidentally ingested. This property has been exploited for medicinal use in traditional healing and has resulted in the production of galantamine for the treatment of Alzheimer's dementia. Long celebrated in art and literature, narcissi are associated with a number of themes in different cultures, ranging from death to good fortune, and as symbols of spring.

The daffodil is the national flower of Wales and the symbol of cancer charities in many countries. The appearance of wild flowers in spring is associated with festivals in many places.

Description

.jpg.webp)

General

Narcissus is a genus of perennial herbaceous bulbiferous geophytes, which die back after flowering to an underground storage bulb. They regrow in the following year from brown-skinned ovoid bulbs with pronounced necks, and reach heights of 5–80 centimetres (2.0–31.5 in) depending on the species. Dwarf species such as N. asturiensis have a maximum height of 5–8 centimetres (2.0–3.1 in), while Narcissus tazetta may grow as tall as 80 centimetres (31 in).[3][4]

The plants are scapose, having a single central leafless hollow flower stem (scape). Several green or blue-green, narrow, strap-shaped leaves arise from the bulb. The plant stem usually bears a solitary flower, but occasionally a cluster of flowers (umbel). The flowers, which are usually conspicuous and white or yellow, sometimes both or rarely green, consist of a perianth of three parts. Closest to the stem (proximal) is a floral tube above the ovary, then an outer ring composed of six tepals (undifferentiated sepals and petals), and a central disc to conical shaped corona. The flowers may hang down (pendant), or be erect. There are six pollen bearing stamens surrounding a central style. The ovary is inferior (below the floral parts) consisting of three chambers (trilocular). The fruit consists of a dry capsule that splits (dehisces) releasing numerous black seeds.[4]

The bulb lies dormant after the leaves and flower stem die back and has contractile roots that pull it down further into the soil. The flower stem and leaves form in the bulb, to emerge the following season. Most species are dormant from summer to late winter, flowering in the spring, though a few species are autumn flowering.[4]

Specific

Vegetative

- Bulbs

The pale brown-skinned ovoid tunicate bulbs have a membranous tunic and a corky stem (base or basal) plate from which arise the adventitious root hairs in a ring around the edge, which grow up to 40 mm in length. Above the stem plate is the storage organ consisting of bulb scales, surrounding the previous flower stalk and the terminal bud. The scales are of two types, true storage organs and the bases of the foliage leaves. These have a thicker tip and a scar from where the leaf lamina became detached. The innermost leaf scale is semicircular only partly enveloping the flower stalk (semisheathed).(see Hanks Fig 1.3). The bulb may contain a number of branched bulb units, each with two to three true scales and two to three leaf bases. Each bulb unit has a life of about four years.[4][5]

Once the leaves die back in summer, the roots also wither. After some years, the roots shorten pulling the bulbs deeper into the ground (contractile roots). The bulbs develop from the inside, pushing the older layers outwards which become brown and dry, forming an outer shell, the tunic or skin. Up to 60 layers have been counted in some wild species. While the plant appears dormant above the ground the flower stalk which will start to grow in the following spring, develops within the bulb surrounded by two to three deciduous leaves and their sheaths. The flower stem lies in the axil of the second true leaf.[4]

- Stems

The single leafless Plant stem stem or scape, appearing from early to late spring depending on the species, bears from 1 to 20 blooms.[6] Stem shape depends on the species, some are highly compressed with a visible seam, while others are rounded. The stems are upright and located at the centre of the leaves. In a few species such as N. hedraeanthus the stem is oblique. The stem is hollow in the upper portion but towards the bulb is more solid and filled with a spongy material.[7]

- Leaves

Narcissus plants have one to several basal leaf leaves which are linear, ligulate or strap-shaped (long and narrow), sometimes channelled adaxially to semiterete, and may (pedicellate) or may not (sessile) have a petiole stalk.[8] The leaves are flat and broad to cylindrical at the base and arise from the bulb.[9] The emerging plant generally has two leaves, but the mature plant usually three, rarely four, and they are covered with a cutin containing cuticle, giving them a waxy appearance. Leaf colour is light green to blue-green. In the mature plant, the leaves extend higher than the flower stem, but in some species, the leaves are low-hanging. The leaf base is encased in a colorless sheath. After flowering, the leaves turn yellow and die back once the seed pod (fruit) is ripe.[4]

Jonquils usually have dark green, round, rush-like leaves.[10]

Reproductive

- Inflorescence

The inflorescence is scapose, the single stem or scape bearing either a solitary flower or forming an umbel with up to 20 blooms.[6] Species bearing a solitary flower include section Bulbocodium and most of section Pseudonarcissus. Umbellate species have a fleshy racemose inflorescence (unbranched, with short floral stalks) with 2 to 15 or 20 flowers, such as N. papyraceus (see illustration, left) and N. tazetta (see Table I).[11][12] The flower arrangement on the inflorescence may be either with (pedicellate) or without (sessile) floral stalks.

Prior to opening, the flower buds are enveloped and protected in a thin dry papery or membranous (scarious) spathe. The spathe consists of a singular bract that is ribbed, and which remains wrapped around the base of the open flower. As the bud grows, the spathe splits longitudinally.[13][14] Bracteoles are small or absent.[7][13][12][15]

- Flowers

The flowers of Narcissus are hermaphroditic (bisexual),[16] have three parts (tripartite), and are sometimes fragrant (see Fragrances).[17] The flower symmetry is actinomorphic (radial) to slightly zygomorphic (bilateral) due to declinate-ascending stamens (curving downwards, then bent up at the tip). Narcissus flowers are characterised by their, usually conspicuous, corona (trumpet).

The three major floral parts (in all species except N. cavanillesii in which the corona is virtually absent - Table I: Section Tapeinanthus) are;

- (i) the proximal floral tube (hypanthium),

- (ii) the surrounding free tepals, and

- (iii) the more distal corona (paraperigon, paraperigonium).

All three parts may be considered to be components of the perianth (perigon, perigonium). The perianth arises above the apex of the inferior ovary, its base forming the hypanthial floral tube.

The floral tube is formed by fusion of the basal segments of the tepals (proximally connate). Its shape is from an inverted cone (obconic) to funnel-shaped (funneliform) or cylindrical, and is surmounted by the more distal corona. Floral tubes can range from long and narrow sections Apodanthi and Jonquilla to rudimentary (N. cavanillesii).[18]

Surrounding the floral tube and corona and reflexed (bent back) from the rest of the perianth are the six spreading tepals or floral leaves, in two whorls which may be distally ascending, reflexed (folded back), or lanceolate. Like many monocotyledons, the perianth is homochlamydeous, which is undifferentiated into separate calyx (sepals) and corolla (petals), but rather has six tepals. The three outer tepal segments may be considered sepals, and the three inner segments petals. The transition point between the floral tube and the corona is marked by the insertion of the free tepals on the fused perianth.[5]

The corona, or paracorolla, is variously described as bell-shaped (funneliform, trumpet), bowl-shaped (cupular, crateriform, cup-shaped) or disc-shaped with margins that are often frilled, and is free from the stamens. Rarely is the corona a simple callose (hardened, thickened) ring. The corona is formed during floral development as a tubular outgrowth from stamens which fuse into a tubular structure, the anthers becoming reduced. At its base, the fragrances which attract pollinators are formed. All species produce nectar at the top of the ovary.[11] Coronal morphology varies from the tiny pigmented disk of N. serotinus (see Table I) or the rudimentary structure in N. cavanillesii to the elongated trumpets of section Pseudonarcissus (trumpet daffodils, Table I).[8][11][12][5]

While the perianth may point forwards, in some species such as N. cyclamineus it is folded back (reflexed, see illustration, left), while in some other species such as N. bulbocodium (Table I), it is reduced to a few barely visible pointed segments with a prominent corona.

The colour of the perianth is white, yellow or bicoloured, with the exception of the night flowering N. viridiflorus which is green. In addition the corona of N. poeticus has a red crenulate margin (see Table I).[9] Flower diameter varies from 12 mm (N. bulbocodium) to over 125 mm (N. nobilis=N. pseudonarcissus subsp. nobilis).[18]

Flower orientation varies from pendent or deflexed (hanging down) as in N. triandrus (see illustration, left), through declinate-ascendant as in N. alpestris = N. pseudonarcissus subsp. moschatus, horizontal (patent, spreading) such as N. gaditanus or N. poeticus, erect as in N. cavanillesii, N. serotinus and N. rupicola (Table I), or intermediate between these positions (erecto-patent).[7][9][11][12][15][19][18]

The flowers of Narcissus demonstrate exceptional floral diversity and sexual polymorphism,[15] primarily by corona size and floral tube length, associated with pollinator groups (see for instance Figs. 1 and 2 in Graham and Barrett[11]). Barrett and Harder (2005) describe three separate floral patterns;

- "Daffodil" form

- "Paperwhite" form

- "Triandrus" form.

The predominant patterns are the 'daffodil' and 'paperwhite' forms, while the "triandrus" form is less common. Each corresponds to a different group of pollinators (See Pollination).[15]

The "daffodil" form, which includes sections Pseudonarcissus and Bulbocodium, has a relatively short, broad or highly funnelform tube (funnel-like), which grades into an elongated corona, which is large and funnelform, forming a broad, cylindrical or trumpet-shaped perianth. Section Pseudonarcissus consists of relatively large flowers with a corolla length of around 50 mm, generally solitary but rarely in inflorescences of 2–4 flowers. They have wide greenish floral tubes with funnel-shaped bright yellow coronas. The six tepals sometimes differ in colour from the corona and may be cream coloured to pale yellow.[16]

The "paperwhite" form, including sections Jonquilla, Apodanthi and Narcissus, has a relatively long, narrow tube and a short, shallow, flaring corona. The flower is horizontal and fragrant.

The "triandrus" form is seen in only two species, N. albimarginatus (a Moroccan endemic) and N. triandrus. It combines features of both the "daffodil" and "paperwhite" forms, with a well-developed, long, narrow tube and an extended bell-shaped corona of almost equal length. The flowers are pendent.[15]

There are six stamens in one to two rows (whorls), with the filaments separate from the corona, attached at the throat or base of the tube (epipetalous), often of two separate lengths, straight or declinate-ascending (curving downwards, then upwards). The anthers are basifixed (attached at their base).[8][5]

The ovary is inferior (below the floral parts) and trilocular (three chambered) and there is a pistil with a minutely three lobed stigma and filiform (thread like) style, which is often exserted (extending beyond the tube).[20][5]

- Fruit

The fruit consists of dehiscent loculicidal capsules (splitting between the locules) that are ellipsoid to subglobose (almost spherical) in shape and are papery to leathery in texture.[7]

- Seeds

The fruit contains numerous subglobose seeds which are round and swollen with a hard coat, sometimes with an attached elaiosome. The testa is black[8] and the pericarp dry.[12]

Most species have 12 ovules and 36 seeds, although some species such as N. bulbocodium have more, up to a maximum of 60. Seeds take five to six weeks to mature. The seeds of sections Jonquilla and Bulbocodium are wedge-shaped and matte black, while those of other sections are ovate and glossy black. A gust of wind or contact with a passing animal is sufficient to disperse the mature seeds.

Chromosomes

Chromosome numbers include 2n=14, 22, 26, with numerous aneuploid and polyploid derivatives. The basic chromosome number is 7, with the exception of N. tazetta, N. elegans and N. broussonetii in which it is 10 or 11; this subgenus (Hermione) was in fact characterised by this characteristic. Polyploid species include N. papyraceus (4x=22) and N. dubius (6x=50).[5]

Phytochemistry

Alkaloids

As with all Amarylidaceae genera, Narcissus contains unique isoquinoline alkaloids. The first alkaloid to be identified was lycorine, from N. pseudonarcissus in 1877. These are considered a protective adaptation and are utilised in the classification of species. Nearly 100 alkaloids have been identified in the genus, about a third of all known Amaryllidaceae alkaloids, although not all species have been tested. Of the nine alkaloid ring types identified in the family, Narcissus species most commonly demonstrate the presence of alkaloids from within the Lycorine (lycorine, galanthine, pluviine) and Homolycorine (homolycorine, lycorenine) groups. Hemanthamine, tazettine, narciclasine, montanine and galantamine alkaloids are also represented. The alkaloid profile of any plant varies with time, location, and developmental stage.[21] Narcissus also contain fructans and low molecular weight glucomannan in the leaves and plant stems.

Fragrances

Fragrances are predominantly monoterpene isoprenoids, with a small amount of benzenoids, although N. jonquilla has both equally represented. Another exception is N. cuatrecasasii which produces mainly fatty acid derivatives. The basic monoterpene precursor is geranyl pyrophosphate, and the commonest monoterpenes are limonene, myrcene, and trans-β-ocimene. Most benzenoids are non-methoxylated, while a few species contain methoxylated forms (ethers), e.g. N. bujei. Other ingredient include indole, isopentenoids and very small amounts of sesquiterpenes. Fragrance patterns can be correlated with pollinators, and fall into three main groups (see Pollination).[17]

Taxonomy

History

Genus valde intricatum et numerosissimis dubiis oppressum

A genus that is very complex and burdened with numerous uncertainties— Schultes & Schultes fil., Syst. Veg. 1829[22]

Early

The genus Narcissus was well known to the ancient Greeks and Romans. In Greek literature Theophrastus[23] and Dioscorides[24] described νάρκισσος, probably referring to N. poeticus, although the exact species mentioned in classical literature cannot be accurately established. Pliny the Elder later introduced the Latin form narcissus.[25][26][27][28] These early writers were as much interested in the plant's possible medicinal properties as they were in its botanical features and their accounts remained influential until at least the Renaissance (see also Antiquity). Mediaeval and Renaissance writers include Albert Magnus and William Turner, but it remained to Linnaeus to formally describe and name Narcissus as a genus in his Species Plantarum (1753) at which time there were six known species.[1][29]

Modern

De Jussieu (1789) grouped Narcissus into a "family",[30][31] which he called Narcissi.[32] This was renamed Amaryllideae by Jaume Saint-Hilaire in 1805,[33] corresponding to the modern Amaryllidaceae. For a while, Narcissus was considered part of Liliaceae (as in the illustration seen here of Narcissus candidissimus),[34][35][36] but then the Amaryllidaceae were split off from it.[37][38]

Various authors have adopted either narrow (e.g. Haworth,[39][40] Salisbury[41]) or wide (e.g.Herbert,[42] Spach[43] ) interpretations of the genus.[44] The narrow view treated many of the species as separate genera.[45] Over time, the wider view prevailed with a major monograph on the genus being published by Baker (1875).[46] One of the more controversial genera was Tapeinanthus,[47][45] but today it is included in Narcissus.[19]

The eventual position of Narcissus within the Amaryllidaceae family only became settled in this century with the advent of phylogenetic analysis and the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group system.[29][48] Within Amaryllidaceae the genus Narcissus belongs to the Narcisseae tribe, one of 13 within the Amaryllidoideae subfamily.[21] It is one of two sister clades corresponding to genera in the Narcisseae,[49] being distinguished from Sternbergia by the presence of a paraperigonium,[4] and is monophyletic.[11]

Subdivision

The infrageneric phylogeny of Narcissus still remains relatively unsettled,[21] the taxonomy having proved complex and difficult to resolve,[12][16][19] due to the diversity of the wild species, the ease with which natural hybridization occurs, and extensive cultivation and breeding accompanied by escape and naturalisation.[21][50] Consequently, the number of accepted species has varied widely.[50]

De Candolle, in the first systematic taxonomy of Narcissus, arranged the species into named groups, and those names have largely endured for the various subdivisions since and bear his name as their authority.[35][36] The situation was confused by the inclusion of many unknown or garden varieties, and it was not until the work of Baker that the wild species were all grouped as sections under one genus, Narcissus.[46]

A common classification system has been that of Fernandes [51][52][53] based on cytology, as modified by Blanchard (1990)[54][55] and Mathew (2002).[19] Another is that of Meyer (1966).[56] Fernandes proposed two subgenera based on basal chromosome numbers, and then subdivided these into ten sections as did Blanchard.[55]

Other authors (e.g. Webb[12][45]) prioritised morphology over genetics, abandoning subgenera, although Blanchard's system has been one of the most influential. While infrageneric groupings within Narcissus have been relatively constant, their status (genera, subgenera, sections, subsections, series, species) has not.[19][21] The most cited system is that of the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) which simply lists ten sections. Three of these are monotypic (contain only one species), while two others contain only two species. Most species are placed in section Pseudonarcissus.[57][58] Many of these subdivisions correspond roughly to the popular names for daffodil types, e.g. Trumpet Daffodils, Tazettas, Pheasant's Eyes, Hoop Petticoats, Jonquils.[19]

The most hierarchical system is that of Mathew, illustrated here -

| Subgenus | Section | Subsection | Series | Type species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Narcissus Pax | Narcissus L. |  N. poeticus L. | ||

| Pseudonarcissus DC syn. Ajax Spach |  N. pseudonarcissus L. | |||

| Ganymedes Salisbury ex Schultes and Schultes fil. |  N. triandrus L. | |||

| Jonquillae De Candolle | Jonquillae DC |  N. jonquilla L. | ||

| Apodanthi (A. Fernandes) D. A. Webb |  N. rupicola Dufour | |||

| Chloranthi D. A. Webb |  N. viridiflorus Schousboe | |||

| Tapeinanthus (Herbert) Traub |  N. cavanillesii A. Barra and G. López | |||

| Hermione (Salisbury) Spach | Hermione syn. Tazettae De Candolle | Hermione | Hermione |  N. tazetta L. |

| Albiflorae Rouy. |  N. papyraceus Ker-Gawler | |||

| Angustifoliae (A. Fernandes) F.J Fernándes-Casas | Click for image N. elegans (Haw.) Spach | |||

| Serotini Parlatore |  N. serotinus L. | |||

| Aurelia (J. Gay) Baker |  N. broussonetii Lagasca | |||

| Corbularia (Salisb.) Pax syn. Bulbocodium De Candolle |  N. bulbocodium L. | |||

Phylogenetics

The phylogenetic analysis of Graham and Barrett (2004) supported the infrageneric division of Narcissus into two clades corresponding to Fernandes' subgenera, but did not support monophyly of all sections.[11] A later extended analysis by Rønsted et al. (2008) with additional taxa confirmed this pattern.[59]

A large molecular analysis by Zonneveld (2008) sought to reduce some of the paraphyly identified by Graham and Barrett. This led to a revision of the sectional structure.[50][58][60] While Graham and Barrett (2004)[11] had determined that subgenus Hermione was monophyletic, Santos-Gally et al. (2011)[58] did not. If two species excluded in the former study are removed from the analysis, the studies are in agreement, the species in question instead forming a clade with subgenus Narcissus. Some so-called nothosections have been proposed, to accommodate natural ('ancient') hybrids (nothospecies).[60]

Species

Estimates of the number of species in Narcissus have varied widely, from anywhere between 16 and almost 160,[50][54] even in the modern era. Linnaeus originally included six species in 1753, by 1784 there were fourteen[61] by 1819 sixteen,[62] and by 1831 Adrian Haworth had described 150 species.[39]

Much of the variation lies in the definition of species. Thus, a very wide view of each species, such as Webb's[12] results in few species, while a very narrow view such as that of Fernandes[51] results in a larger number.[19] Another factor is the status of hybrids, with a distinction between "ancient hybrids" and "recent hybrids". The term "ancient hybrid" refers to hybrids found growing over a large area, and therefore now considered as separate species, while "recent hybrid" refers to solitary plants found amongst their parents, with a more restricted range.[50]

Fernandes (1951) originally accepted 22 species,[53] Webb (1980) 27.[12] By 1968, Fernandes had 63 species,[51] Blanchard (1990) 65 species,[54] and Erhardt (1993) 66.[63] In 2006 the Royal Horticultural Society's (RHS) International Daffodil Register and Classified List [57][64][65] listed 87 species, while Zonneveld's genetic study (2008) resulted in only 36.[50] As of September 2014, the World Checklist of Selected Plant Families accepts 52 species, along with at least 60 hybrids,[66] while the RHS has 81 accepted names in its October 2014 list.[67]

Evolution

Within the Narcisseae, Narcissus (western Mediterranean) diverged from Sternbergia (Eurasia) some time in the Late Oligocene to Early Miocene eras, around 29.3–18.1 Ma. Later, the genus divided into the two subgenera (Hermione and Narcissus) between 27.4 and 16.1 Ma. The divisions between the sections of Hermione then took place during the Miocene period 19.9–7.8 Ma.[58] Narcissus appears to have arisen in the area of the Iberian peninsula, southern France and northwestern Italy. Subgenus Hermione in turn arose in the southwestern Mediterranean and Northwest Africa.[58]

Names and etymology

Narcissus

The derivation of the Latin narcissus[68] is from Greek νάρκισσος narkissos.[69][70] According to Plutarch narkissos has been connected because of the plant's narcotic properties, with narkē "numbness";[69][71] it may also be connected with hell.[72] On the other hand, its etymology is considered to be clearly Pre-Greek by Beekes.[73]

It is frequently linked to the myth of Narcissus, who became so obsessed with his own reflection in water that he drowned and the narcissus plant sprang from where he died. There is no evidence for the flower being named after Narcissus. Narcissus poeticus, which grows in Greece, has a fragrance that has been described as intoxicating.[74] Pliny wrote that the plant was named for its fragrance (ναρκάω narkao, "I grow numb" ), rather than Narcissus.[21][25][75][76][77] Furthermore, there were accounts of narcissi growing long before the story of Narcissus appeared (see Greek culture).[72][78][Note 2] It has also been suggested that narcissi bending over streams represent the youth admiring his reflection.[79] Linnaeus used the Latin name "narcissus" for the plant but was preceded by others such as Matthias de l'Obel (1591)[80] and Clusius (1576).[81] The name Narcissus was not uncommon for men in Roman times.

The plural form of the common name "narcissus" has been the cause of some confusion. Dictionaries list "narcissi", "narcissuses" and "narcissus".[74][82][83] However, texts on usage such as Garner[84] and Fowler[85] state that "narcissi" is the preferred form. The common name narcissus should not be capitalised.

Daffodil

The name "daffodil" is derived from "affodell", a variant of asphodel.[86] The narcissus was frequently referred to as the asphodel[75] (see Antiquity). Asphodel in turn appears to come from the Greek "asphodelos" (Greek: ἀσφόδελος).[75][87][88][89] The reason for the introduction of the initial "d" is not known.[90] From at least the 16th century, "daffadown dilly" and "daffydowndilly" have appeared as alternative names.[74] Other names include "Lent lily".[91][92]

In other languages

The Hokkien name for Narcissus, chúi-sian, can be literally translated as "water fairy", where chúi (水) refers to water and sian (仙) refers to immortals. It is the official provincial flower of Fujian.[93]

Distribution and habitat

Distribution

Although the family Amaryllidaceae are predominantly tropical or subtropical as a whole, Narcissus occurs primarily in Mediterranean region, with a centre of diversity in the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal).[19] A few species extend the range into southern France, Italy, the Balkans (N. poeticus, N. serotinus, N. tazetta), and the Eastern Mediterranean (N. serotinus)[19][4] including Israel (N. tazetta).[11][21] The occurrence of N. tazetta in western and central Asia as well as East Asia are considered introductions, albeit ancient[4] (see Eastern cultures). While the exact northern limit of the natural range is unknown, the occurrences of wild N. pseudonarcissus in Great Britain, middle and northern Europe are similarly considered ancient introductions.[19][94][95]

While the Amaryllidaceae are not native to North America, Narcissus grows well in USDA hardiness zones 3B through 10, which encompass most of the United States and Canada.[96]

N. elegans occurs on the North West African Coast (Morocco and Libya), as well as the coastline of Corsica, Sardinia and Italy, and N. bulbocodium between Tangier and Algiers and Tangier to Marrakech, but also on the Iberian Peninsula. N. serotinus is found along the entire Mediterranean coast. N. tazetta occurs as far east as Iran and Kashmir. Since this is one of the oldest species found in cultivation, it is likely to have been introduced into Kashmir. N. poeticus and N. pseudonarcissus have the largest distribution ranges. N. poeticus ranges from the Pyrenees along the Romanian Carpathians to the Black Sea and along the Dalmatian coast to Greece. N. pseudonarcissus ranges from the Iberian Peninsula, via the Vosges Mountains to northern France and Belgium, and the United Kingdom where there are still wild stocks in Southern Scotland. The only occurrence in Luxembourg is located near Lellingen, in the municipality of Kiischpelt. In Germany it is found mainly in the nature reserve at Perlenbach-Fuhrtsbachtal and the Eifel National Park, where in the spring at Monschau the meadows are teeming with yellow blooms.[97] One of the most easterly occurrences can be found at Misselberg near Nassau on the Lahn.

However, unlike the above examples, most species have very restricted endemic ranges[58][98] which may overlap resulting in natural hybrids.[50] For instance in the vicinity of the Portuguese city of Porto where both N. pseudonarcissus and N. triandrus occur there are found various intersections of the two species while in a small area along part of the Portuguese Mondego river are found intersectional hybrids between N. scaberulus and N. triandrus.

The biogeography demonstrates a phylogenetic association, for instance subgenus Hermione having a lowland distribution, but subgenus Narcissus section Apodanthi being montane and restricted to Morocco, Spain and Portugal. The remaining sections within subgenus Narcissus include both lowland and mountain habitats.[58] Section Pseudonarcissus, although widely naturalised, is endemic to the Baetic Ranges of the southeastern Iberian peninsula.[16]

Habitats

Their native habitats are very varied, with different elevations, bioclimatic areas and substrates,[58] being found predominantly in open spaces ranging from low marshes to rocky hillsides and montane pastures, and including grassland, scrub, woods, river banks and rocky crevices.[11][21] Although requirements vary, overall there is a preference for acidic soils, although some species will grow on limestone. Narcissus scaberulus will grow on granite soils where it is moist in the growing season but dry in the summer, while Narcissus dubius thrives best in regions with hot and dry summers.

The Pseudonarcissus group in their natural habitat prefers humid situations such as stream margins, springs, wet pastures, clearings of forests or shrublands with humid soils, and moist hillsides. These habitats tend to be discontinuous in the Mediterranean mountains, producing discrete isolated populations.[16] In Germany, which has relatively little limestone, Narcissus pseudonarcissus grows in small groups on open mountain meadows or in mixed forests of fir, beech, oak, alder, ash and birch trees with well-drained soil.

Ecology

Life cycle

Narcissus are long-lived perennial geophytes with winter-growing and summer-dormant bulbs[16] that are mainly synanthous (leaves and flowers appearing at the same time).[4] While most species flower in late winter to spring, five species are autumn flowering (N. broussonetii, N. cavanillesii, N. elegans, N. serotinus, N. viridiflorus).[11] By contrast, these species are hysteranthous (leaves appear after flowering).[4]

Flower longevity varies by species and conditions, ranging from 5–20 days.[99] After flowering leaf and root senescence sets in, and the plant appears to be 'dormant' until the next spring, conserving moisture. However, the dormant period is also one of considerable activity within the bulb primordia. It is also a period during which the plant bulb may be susceptible to predators . Like many bulb plants from temperate regions, a period of exposure to cold is necessary before spring growth can begin. This protects the plant from growth during winter when intense cold may damage it. Warmer spring temperatures then initiate growth from the bulb. Early spring growth confers a number of advantages, including relative lack of competition for pollinators, and lack of deciduous shading. [4] The exception to requiring cold temperatures to initiate flowering is N. tazetta.[5]

Plants may spread clonally through the production of daughter bulbs and division, producing clumps.[16] Narcissus species hybridise readily, although the fertility of the offspring will depend on the parental relationship.[21]

Pollination

The flowers are insect-pollinated, the major pollinators being bees, butterflies, flies, and hawkmoths, while the highly scented night-flowering N. viridiflorus is pollinated by crepuscular moths. Pollination mechanisms fall into three groups corresponding to floral morphology (see Description - Flowers).[99]

- 'Daffodil' form. Pollinated by bees seeking pollen from anthers within the corona. The broad perianth allows bees (Bombus, Anthophora, Andrena) to completely enter the flower in their search for nectar and/or pollen. In this type, the stigma lies in the mouth of the corona, extending beyond the six anthers, whose single whorl lies well within the corona. The bees come into contact with the stigma before their legs, thorax and abdomen contact the anthers, and this approach herkogamy causes cross pollination.

- 'Paperwhite' form. These are adapted to long-tongued Lepidoptera, particularly sphingid moths such as Macroglossum, Pieridae and Nymphalidae, but also some long-tongued bees, and flies, all of which are primarily seeking nectar. The narrow tube admits only the insect's proboscis, while the short corona serves as a funnel guiding the tip of the proboscis into the mouth of the perianth tube. The stigma is placed either in the mouth of the tube, just above two whorls of three anthers, or hidden well below the anthers. The pollinators then carry pollen on their probosci or faces. The long-tongued bees cannot reach the nectar at the tube base and so collect just pollen.

- 'Triandrus' form. Pollinated by long-tongued solitary bees (Anthophora, Bombus), which forage for both pollen and nectar. The large corona allows the bees to crawl into the perianth but then the narrow tube prevents further progress, causing them to probe deeply for nectar. The pendant flowers prevent pollination by Lepidoptera. In N. albimarginatus there may be either a long stigma with short and mid-length anthers or a short stigma and long anthers (dimorphism). In N. triandrus there are three patterns of sexual organs (trimophism) but all have long upper anthers but vary in stigma position and the length of the lower anthers.[11][15]

Allogamy (outcrossing) on the whole is enforced through a late-acting (ovarian) self-incompatibility system, but some species such as N. dubius and N. longispathus are self-compatible producing mixtures of selfed and outcrossed seeds.[17][15]

Pests and diseases

Diseases of Narcissus are of concern because of the economic consequences of losses in commercial cultivation. Pests include viruses, bacteria, and fungi as well as arthropods and gastropods. For control of pests, see Commercial uses.

Aphids such as Macrosiphum euphorbiae can transmit viral diseases which affect the colour and shape of the leaves, as can nematodes.[100] Up to twenty-five viruses have been described as being able to infect narcissi.[101][102][103] These include the Narcissus common latent virus (NCLV, Narcissus mottling-associated virus[104]),[Note 3] Narcissus latent virus (NLV, Narcissus mild mottle virus[104]) which causes green mottling near leaf tips,[105][106] Narcissus degeneration virus (NDV),[107] Narcissus late season yellows virus (NLSYV) which occurs after flowering, streaking the leaves and stems,[108][109] Narcissus mosaic virus, Narcissus yellow stripe virus (NYSV, Narcissus yellow streak virus[104]), Narcissus tip necrosis virus (NTNV) which produces necrosis of leaf tips after flowering[110] and Narcissus white streak virus (NWSV).[111]

Less host specific viruses include Raspberry ringspot virus, Nerine latent virus (NeLV) =Narcissus symptomless virus,[112] Arabis mosaic virus (ArMV),[113] Broad Bean Wilt Viruses (BBWV)[114] Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV), Tomato black ring virus (TBRV), Tomato ringspot virus (TomRSV) and Tobacco rattle virus (TRV).[114][111]

Of these viruses the most serious and prevalent are NDV, NYSV and NWSV.[111][102] NDV is associated with chlorotic leaf striping in N. tazetta.[107] Infection with NYSV produces light or grayish-green, or yellow stripes or mottles on the upper two-thirds of the leaf, which may be roughened or twisted. The flowers which may be smaller than usual may also be streaked or blotched. NWSV produces greenish-purple streaking on the leaves and stem turning white to yellow, and premature senescence reducing bulb size and yield.[101] These viruses are primarily diseases of commercial nurseries. The growth inhibition caused by viral infection can cause substantial economic damage.[115][116][117]

Bacterial disease is uncommon in Narcissus but includes Pseudomonas (bacterial streak) and Pectobacterium carotovorum sp. carotovorum (bacterial soft rot).[111]

More problematic for non-commercial plants is the fungus, Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. narcissi, which causes basal rot (rotting of the bulbs and yellowing of the leaves). This is the most serious disease of Narcissus. Since the fungus can remain in the soil for many years it is necessary to remove infected plants immediately, and to avoid planting further narcissi at that spot for a further five years. Not all species and cultivars are equally susceptible. Relatively resistant forms include N. triandrus, N. tazetta and N. jonquilla.[118][111][119][120]

Another fungus which attacks the bulbs, causing narcissus smoulder, is Botrytis narcissicola (Sclerotinia narcissicola) and other species of Botrytis, including Botrytis cinerea,[121][122] particularly if improperly stored. Copper sulfate is used to combat the disease, and infected bulbs are burned. Blue mould rot of bulbs may be caused by infection with species of Penicillium, if they have become damaged either through mechanical injury or infestation by mites (see below).[123] Species of Rhizopus (e.g. Rhizopus stolonifer, Rhizopus nigricans) cause bulb soft rot[116][124] and Sclerotinia bulborum, black slime disease.[125] A combination of both Peyronellaea curtisii (Stagonosporopsis curtisii) and Botrytis narcissicola causes neck rot in the bulbs.[111]

Fungi affecting the roots include Nectria radicicola (Cylindrocarpon destructans), a cause of root rot[125] and Rosellinia necatrix causing white root rot,[126] while others affect root and bulb, such as Aspergillus niger (black mold), and species of Trichoderma, including T. viride and T. harzianum (=T. narcissi) responsible for green mold.[124]

Other fungi affect the remainder of the plant. Another Botrytis fungus, Botrytis polyblastis (Sclerotinia polyblastis) causes brown spots on the flower buds and stems (narcissus fire), especially in damp weather and is a threat to the cut flower industry.[127][128] Ramularia vallisumbrosae is a leaf spot fungus found in warmer climates, causing narcissus white mould disease.[129] Peyronellaea curtisii, the Narcissus leaf scorch, also affects the leaves[115][116][130][131][132] as does its synanamorph, Phoma narcissi (leaf tip blight).[133][111] Aecidium narcissi causes rust lesions on leaves and stems.[125]

Arthropods that are Narcissus pests include insects such as three species of fly that have larvae that attack the plants, the narcissus bulb fly Merodon equestris, and two species of hoverflies, the lesser bulb flies Eumerus tuberculatus[134] and Eumerus strigatus. The flies lay their eggs at the end of June in the ground around the narcissi, a single female fly being able to lay up to fifty eggs. The hatching larvae then burrow through the soil towards the bulbs and consume their interiors. They then overwinter in the empty bulb shell, emerging in April to pupate in the soil, from which the adult fly emerges in May.[115][135] The larvae of some moths such as Korscheltellus lupulina (the common swift moth) attack Narcissus bulbs.[136][115]

Other arthropods include Mites such as Steneotarsonemus laticeps (Bulb scale mite),[137] Rhizoglyphus and Histiostoma infest mainly stored bulbs and multiply particularly at high ambient temperature, but do not attack planted bulbs.[115]

Planted bulbs are susceptible to nematodes, the most serious of which is Ditylenchus dipsaci (Narcissus eelworm), the main cause of basal plate disease[138] in which the leaves turn yellow and become misshapen. Infested bulbs have to be destroyed; where infestation is heavy avoiding planting further narcissi for another five years.[115][139][140][141] Other nematodes include Aphelenchoides subtenuis, which penetrates the roots causing basal plate disease[138][142] and Pratylenchus penetrans (lesion nematode) the main cause of root rot in narcissi. [143][111] Other nematodes such as the longodorids (Longidorus spp. or needle nematodes and Xiphinema spp. or dagger nematodes) and the stubby-root nematodes or trichodorids (Paratrichodorus spp. and Trichodorus spp.) can also act as vectors of virus diseases, such as TBRV and TomRSV, in addition to causing stunting of the roots.[100][142]

Gastropods such as snails and slugs also cause damage to growth.[115][116][111]

Conservation

Many of the smallest species have become extinct, requiring vigilance in the conservation of the wild species.[4][21][75][144] Narcissi are increasingly under threat by over-collection and threats to their natural habitats by urban development and tourism. N. cyclamineus has been considered to be either extinct or exceedingly rare[19] but is not currently considered endangered, and is protected.[145] The IUCN Red List describes five species as 'Endangered' (Narcissus alcaracensis, Narcissus bujei, Narcissus longispathus, Narcissus nevadensis, Narcissus radinganorum). In 1999 three species were considered endangered, five as vulnerable and six as rare.[4]

In response a number of species have been granted protected species status and protected areas (meadows) have been established such as the Negraşi Daffodil Meadow in Romania, or Kempley Daffodil Meadow in the UK. These areas often host daffodil festivals in the spring.

Cultivation

History

Magna cura non indigent Narcissi

Most easy of cultivation is the Narcissus

N. serotinus, John Gerard, The Herball 1597

N. serotinus, John Gerard, The Herball 1597_-_Classis_Verna_52.jpg.webp) Narcissi, Hortus Eystettensis 1613

Narcissi, Hortus Eystettensis 1613 N. poeticus, Thomas Hale, Eden: Or, a Compleat Body of Gardening 1757

N. poeticus, Thomas Hale, Eden: Or, a Compleat Body of Gardening 1757 Narcissus, Peter Lauremberg 1632

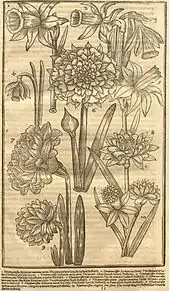

Narcissus, Peter Lauremberg 1632 Narcissi, John Parkinson, Paradisus Terrestris 1629. (8. Great Double Yellow Spanish Daffodil)

Narcissi, John Parkinson, Paradisus Terrestris 1629. (8. Great Double Yellow Spanish Daffodil)

Of all the flowering plants, the bulbous have been the most popular for cultivation.[147] Of these, narcissi are one of the most important spring flowering bulb plants in the world.[148][8] Indigenous in Europe, the wild populations of the parent species had been known since antiquity. Narcissi have been cultivated from at least as early as the sixteenth century in the Netherlands, when large numbers of bulbs where imported from the field, particularly Narcissus hispanicus, which soon became nearly extinct in its native habitat of France and Spain, though still found in the southern part of that country.[149] The only large-scale production at that time related to the double narcissus "Van Sion" and cultivars of N. tazetta imported in 1557.[150]

Cultivation is also documented in Britain at this time,[151][152][153] although contemporary accounts show it was well known as a favourite garden and wild flower long before that and was used in making garlands.[154] This was a period when the development of exotic formal gardens and parks was becoming popular, particularly in what is known as the "Oriental period" (1560–1620). In his Hortus Medicus (1588), the first catalogue of a German garden's plants,[155] Joachim Camerarius the Younger states that nine different types of daffodils were represented in his garden in Nuremberg.[156] After his death in 1598, his plants were moved by Basilius Besler to the gardens they had designed at Willibaldsburg, the bishop's palace at Eichstätt, Upper Bavaria. That garden is described in Besler's Hortus Eystettensis (1613) by which time there were 43 different types present.[157] Another German source at this time was Peter Lauremberg who gives an account of the species known to him and their cultivation in his Apparatus plantarius: de plantis bulbosis et de plantis tuberosis (1632).[158]

While Shakespeare's daffodil is the wild or true English daffodil (N. pseudonarcissus),[154] many other species were introduced, some of which escaped and naturalised, particularly N. biflorus (a hybrid) in Devon and the west of England.[159] Gerard, in his extensive discussion of daffodils, both wild and cultivated ("bastard daffodils") described twenty four species in London gardens (1597),[159][160][161] ("we have them all and every one of them in our London gardens, in great abundance", p. 114).

In the early seventeenth century, Parkinson helped to ensure the popularity of the daffodil as a cultivated plant[159] by describing a hundred different varieties in his Paradisus Terrestris (1629),[162] and introducing the great double yellow Spanish daffodil (Pseudonarcissus aureus Hispanicus flore pleno or Parkinson's Daffodil, see illustration) to England.[163]

I thinke none ever had this kind before myselfe nor did I myself ever see it before the year 1618 for it is of mine own raising and flowering first in my own garden

Although not achieving the sensationalism of tulips, daffodils and narcissi have been much celebrated in art and literature . The largest demand for narcissi bulbs were large trumpet daffodils, N. poeticus and N. bulbocodium, and Istanbul became important in the shipping of bulbs to western Europe. By the early baroque period both tulips and narcissi were an important component of the spring garden. By 1739 a Dutch nursery catalogue listed 50 different varieties. A catalog of a Dutch nursery from 1739 already counted 50 varieties. In 1757 Hill gave an account of the history and cultivation of the daffodil in his edited version of the works of Thomas Hale, writing "The garden does not afford, in its Kind, a prettier plant than this; nor do we know one that has been so early, or so honorably mention'd by all Kinds of Writers" (see illustration).[164] Interest grew further when varieties that could be grown indoors became available, primarily the bunch flowered (multiple flower heads) N. tazetta (Polyanthus Narcissus).[147] However interest varied by country. Maddock (1792) does not include narcissi in his list of the eight most important cultivated flowering plants in England,[165] whereas in the Netherlands van Kampen (1760) stated that N. tazetta (Narcisse à bouquet) is the fifth most important – "Le Narcisse à bouquet est la premiere fleur, après les Jacinthes, les Tulipes les Renoncules, et les Anemones, (dont nous avons déja parlé,) qui merite nôtre attention".[166][167] Similarly Philip Miller, in his Gardeners Dictionary (1731–1768) refers to cultivation in Holland, Flanders and France, but not England,[168] because it was too difficult, a similar observation was made by Sir James Justice at this time.[169] However, for most species of Narcissus Lauremberg's dictum Magna cura non indigent Narcissi was much cited.[170]

Narcissi became an important horticultural crop in Western Europe in the latter part of the nineteenth century, beginning in England between 1835 and 1855 and the end of the century in the Netherlands.[5] By the beginning of the twentieth century 50 million bulbs of N. Tazetta "Paperwhite" were being exported annually from the Netherlands to the United States. With the production of triploids such as "Golden Spur", in the late nineteenth century, and in the beginning of the twentieth century, tetraploids like "King Alfred" (1899), the industry was well established, with trumpet daffodils dominating the market.[149] The Royal Horticultural Society has been an important factor in promoting narcissi, holding the first Daffodil Conference in 1884,[171] while the Daffodil Society, the first organisation dedicated to the cultivation of narcissi was founded in Birmingham in 1898. Other countries followed and the American Daffodil Society which was founded in 1954 publishes The Daffodil Journal quarterly, a leading trade publication.

Narcissi are now popular as ornamental plants for gardens, parks and as cut flowers, providing colour from the end of winter to the beginning of summer in temperate regions. They are one of the most popular spring flowers[172] and one of the major ornamental spring flowering bulb crops, being produced both for their bulbs and cut flowers, though cultivation of private and public spaces is greater than the area of commercial production.[21] Over a century of breeding has resulted in thousands of varieties and cultivars being available from both general and specialist suppliers.[11] They are normally sold as dry bulbs to be planted in late summer and autumn. They are one of the most economically important ornamental plants.[11][21] Plant breeders have developed some daffodils with double, triple, or ambiguously multiple rows and layers of segments.[6] Many of the breeding programs have concentrated on the corona (trumpet or cup), in terms of its length, shape, and colour, and the surrounding perianth[19] or even as in varieties derived from N. poeticus a very reduced form.

In gardens

While some wild narcissi are specific in terms of their ecological requirements, most garden varieties are relatively tolerant of soil conditions,[173] however very wet soils and clay soils may benefit from the addition of sand to improve drainage.[174] The optimum soil is a neutral to slightly acid pH of 6.5–7.0.[173]

Bulbs offered for sale are referred to as either 'round' or 'double nose'. Round bulbs are circular in cross section and produce a single flower stem, while double nose bulbs have more than one bulb stem attached at the base and produce two or more flower stems, but bulbs with more than two stems are unusual.[175] Planted narcissi bulbs produce daughter bulbs in the axil of the bulb scales, leading to the dying off the exterior scales.[173] To prevent planted bulbs forming more and more small bulbs, they can be dug up every 5–7 years, and the daughters separated and replanted separately, provided that a piece of the basal plate, where the rootlets are formed, is preserved. For daffodils to flower at the end of the winter or early spring, bulbs are planted in autumn (September–November). This plant does well in ordinary soil but flourishes best in rich soil. Daffodils like the sun but also accept partial shade exposure.

Narcissi are well suited for planting under small thickets of trees, where they can be grouped as 6–12 bulbs.[176] They also grow well in perennial borders,[173] especially in association with day lilies which begin to form their leaves as the narcissi flowers are fading.[174] A number of wild species and hybrids such as "Dutch Master", "Golden Harvest", "Carlton", "Kings Court" and "Yellow Sun" naturalise well in lawns,[173] but it is important not to mow the lawn till the leaves start to fade, since they are essential for nourishing the bulb for the next flowering season.[173] Blue Scilla and Muscari which also naturalise well in lawns and flower at the same time as narcissus, make an attractive contrast to the yellow flowers of the latter. Unlike tulips, narcissi bulbs are not attractive to rodents and are sometimes planted near tree roots in orchards to protect them.[177]

Propagation

The commonest form of commercial propagation is by twin-scaling, in which the bulbs are cut into many small pieces but with the two scales still connected by a small fragment of the basal plate. The fragments are disinfected and placed in nutrient media. Some 25–35 new plants can be produced from a single bulb after four years. Micropropagation methods are not used for commercial production but are used for establishing commercial stock.[178] [140]

Breeding

For commercial use, varieties with a minimum stem length of 30 centimetres (12 in) are sought, making them ideal for cut flowers. Florists require blooms that only open when they reach the retail outlet. For garden plants the objectives are to continually expand the colour palette and to produce hardy forms, and there is a particular demand for miniature varieties. The cultivars so produced tend to be larger and more robust than the wild types.[4] The main species used in breeding are N. bulbocodium, N. cyclamineus, N. jonquilla, N. poeticus, N. pseudonarcissus, N. serotinus and N. tazetta.[179]

Narcissus pseudonarcissus gave rise to trumpet cultivars with coloured tepals and corona, while its subspecies N. pseudonarcissus subsp. bicolor was used for white tepaled varieties. To produce large cupped varieties, N. pseudonarcissus was crossed with N. poeticus, and to produce small cupped varieties back crossed with N. poeticus. Multiheaded varieties, often called "Poetaz" are mainly hybrids of N. poeticus and N. tazetta.[4]

Classification

For horticultural purposes, all Narcissus cultivars are split into 13 divisions as first described by Kington (1998),[180] for the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS),[6] based partly upon flower form (shape and length of corona), number of flowers per stem, flowering period and partly upon genetic background. Division 13, which includes wild daffodils, is the exception to this scheme.[181] The classification is a useful tool for planning planting. Most commercially available narcissi come from Divisions 1 (Trumpet), 2 (Large cupped) and 8 (Tazetta).

Growers register new daffodil cultivars by name and colour with the Royal Horticultural Society, which is the international registration authority for the genus.[64] Their International Daffodil Register is regularly updated with supplements available online[64] and is searchable.[19][65] The most recent supplement (2014) is the sixth (the fifth was published in 2012).[182] More than 27,000 names were registered as of 2008,[182] and the number has continued to grow. Registered daffodils are given a division number and colour code[183] such as 5 W-W ("Thalia").[184] In horticultural usage it is common to also find an unofficial Division 14: Miniatures, which although drawn from the other 13 divisions, have their miniature size in common.[185] Over 140 varieties have gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit (See List of Award of Garden Merit narcissus).

Colour code

Daffodil breeding has introduced a wide range of colours, in both the outer perianth tepal segment and the inner corona. In the registry, daffodils are coded by the colours of each of these two parts. Thus "Geranium", Tazetta (Division 8) as illustrated here with a white outer perianth and orange corona is classified as 8 W-O.

Toxicity

Pharmacology

All Narcissus species contain the alkaloid poison lycorine, mostly in the bulb but also in the leaves.[186] Members of the monocot subfamily Amaryllidoideae present a unique type of alkaloids, the norbelladine alkaloids, which are 4-methylcatechol derivatives combined with tyrosine. They are responsible for the poisonous properties of a number of the species. Over 200 different chemical structures of these compounds are known, of which 79 or more are known from Narcissus alone.[187]

The toxic effects of ingesting Narcissus products for both humans and animals (such as cattle, goats, pigs, and cats) have long been recognised and they have been used in suicide attempts. Ingestion of N. pseudonarcissus or N. jonquilla is followed by salivation, acute abdominal pains, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, then neurological and cardiac events, including trembling, convulsions, and paralysis. Death may result if large quantities are consumed.

The toxicity of Narcissus varies with species, N. poeticus being more toxic than N. pseudonarcissus, for instance. The distribution of toxins within the plant also varies, for instance, there is a five times higher concentration of alkaloid in the stem of N. papyraceus than in the bulb, making it dangerous to herbivores more likely to consume the stem than the bulb, and is part of the plant's defence mechanisms. The distribution of alkaloids within tissues may also reflect defence against parasites.[21] The bulbs can also be toxic to other nearby plants, including roses, rice, and cabbages, inhibiting growth.[21] For instance placing cut flowers in a vase alongside other flowers shortens the life of the latter.[188]

Poisoning

Many cases of poisoning or death have occurred when narcissi bulbs have been mistaken for leeks or onions and cooked and eaten. Recovery is usually complete in a few hours without any specific intervention. In more severe cases involving ingestion of large quantities of bulbs, activated carbon, salts and laxatives may be required, and for severe symptoms intravenous atropine and emetics or stomach pumping may be indicated. However, ingestion of large quantities accidentally is unusual because of a strong unpleasant taste. When narcissi were compared with a number of other plants not normally consumed by animals, narcissi were the most repellent, specifically N. pseudonarcissus. Consequently, narcissus alkaloids have been used as repellents and may also discourage fungi, molds, and bacteria.[21]

On 1 May 2009, a number of schoolchildren fell ill at Gorseland Primary School in Martlesham Heath, Suffolk, England, after a daffodil bulb was added to soup during a cookery class.[186]

Topical effects

One of the most common dermatitis problems for flower pickers, packers, florists, and gardeners, "daffodil itch", involves dryness, fissures, scaling, and erythema in the hands, often accompanied by subungual hyperkeratosis (thickening of the skin beneath the nails). It is blamed on exposure to calcium oxalate, chelidonic acid or alkaloids such as lycorine in the sap, either due to a direct irritant effect or an allergic reaction.[189][190] It has long been recognised that some cultivars provoke dermatitis more readily than others. N. pseudonarcissus and the cultivars "Actaea", "Camparelle", "Gloriosa", "Grande Monarque", "Ornatus", "Princeps" and "Scilly White" are known to do so.[21][191]

If bulb extracts come into contact with wounds, both central nervous system and cardiac symptoms may result. The scent can also cause toxic reactions such as headaches and vomiting from N. bulbocodium.[21]

Uses

Traditional medicine

Despite the lethal potential of Narcissus alkaloids, they have been used for centuries as traditional medicines for a variety of complaints, including cancer. Plants thought to be N. poeticus and N. tazetta are described in the Bible in the treatment for what is thought to be cancer.[188][192][193][194] In the Classical Greek world Hippocrates (ca. B.C. 460–370) recommended a pessary prepared from narcissus oil for uterine tumors, a practice continued by Pedanius Dioscorides (ca. A.D. 40–90) and Soranus of Ephesus (A.D. 98–138) in the first and second centuries A.D., while the Roman Pliny the Elder (A.D. 23–79), advocated topical use.[188] The bulbs of N. poeticus contain the antineoplastic agent narciclasine. This usage is also found in later Arabian, North African, Central American and Chinese medicine during the Middle Ages.[188] In China N. tazetta var. chinensis was grown as an ornamental plant but the bulbs were applied topically to tumors in traditional folk medicine. These bulbs contain pretazettine, an active antitumor compound.[21][194][195]

Narcissus products have received a variety of other uses. The Roman physician Aulus Cornelius Celsus listed narcissus root in De Medicina among medical herbs, described as emollient, erodent, and "powerful to disperse whatever has collected in any part of the body". N. tazetta bulbs were used in Turkey as a remedy for abscesses in the belief they were antiphlogistic and analgesic. Other uses include the application to wounds, strains, painful joints, and various local ailments as an ointment called 'Narcissimum'. Powdered flowers have also been used medically, as an emetic, a decongestant and for the relief of dysentery, in the form of a syrup or infusion. The French used the flowers as an antispasmodic, the Arabs the oil for baldness and also an aphrodisiac. In the eighteenth century the Irish herbal of John K'Eogh recommended pounding the roots in honey for use on burns, bruises, dislocations and freckles, and for drawing out thorns and splinters. N. tazetta bulbs have also been used for contraception, while the flowers have been recommended for hysteria and epilepsy.[21] In the traditional Japanese medicine of kampo, wounds were treated with narcissus root and wheat flour paste;[196] the plant, however, does not appear in the modern kampo herb list.

There is also a long history of the use of Narcissus as a stimulant and to induce trance like states and hallucinations. Sophocles referred to the narcissus as the "Chaplet of the infernal Gods",[72] a statement frequently wrongly attributed to Socrates (see Antiquity).[21]

Biological properties

Extracts of Narcissus have demonstrated a number of potentially useful biological properties including antiviral, prophage induction, antibacterial, antifungal, antimalarial, insecticidal, cytotoxic, antitumor, antimitotic, antiplatelet, hypotensive, emetic, acetylcholine esterase inhibitory, antifertility, antinociceptive, chronotropic, pheromone, plant growth inhibitor, and allelopathic.[21] An ethanol extract of Narcissus bulbs was found effective in one mouse model of nociception, para-benzoquinone induced abdominal constriction, but not in another, the hot plate test.[197] Most of these properties are due to alkaloids, but some are also due to mannose-binding lectins. The most-studied alkaloids in this group are galantamine (galanthamine),[198] lycorine, narciclasine, and pretazettine.

It is likely that the traditional use of narcissi for the treatment of cancer was due to the presence of isocarbostyril constituents such as narciclasine, pancratistatin and their congeners. N. poeticus contains about 0.12g of narciclasine per kg of fresh bulbs.[188]

Acetylcholine esterase inhibition has attracted the most interest as a possible therapeutic intervention, with activity varying by a thousandfold between species, and the greatest activity seen in those that contain galantamine or epinorgalanthamine.[59]

The rodent repellant properties of Narcissus alkaloids have been utilised in horticulture to protect more vulnerable bulbs.[199]

Therapeutics

Of all the alkaloids, only galantamine has made it to therapeutic use in humans, as the drug galantamine for Alzheimer's disease. Galantamine is an acetylcholine esterase inhibitor which crosses the blood brain barrier and is active within the central nervous system.[21] Daffodils are grown commercially near Brecon in Powys, Wales, to produce galantamine.[200]

Commercial uses

Throughout history the scent of narcissi has been an important ingredient of perfumes, a quality that comes from essential oils rather than alkaloids.[21] Narcissi are also an important horticultural crop,[50][75] and source of cut flowers (floriculture).

The Netherlands, which is the most important source of flower bulbs worldwide is also a major centre of narcissus production. Of 16,700 hectares (ha) under cultivation for flower bulbs, narcissi account for about 1,800 hectares. In the 1990s narcissus bulb production was at 260 million, sixth in size after tulips, gladioli, irises, crocuses and lilies and in 2012 it was ranked third.[148] About two-thirds of the area under cultivation is dedicated to about 20 of the most popular varieties. In the 2009/2010 season, 470 cultivars were produced on 1578 ha. By far the largest area cultivated is for the miniature 'Tête-à-Tête', followed at some distance by 'Carlton'. The largest production cultivars are shown in Table II.[201]

| Cultivar | Division | Colour | Area (ha) |

|---|---|---|---|

| "Tête-à-Tête" | 6: Cyclamineus | Yellow | 663 |

| "Carlton" | 2: Large cup | Yellow | 54 |

| "Bridal Crown" | 4: Double | White–Yellow | 51 |

| "Dutch Master" | 1: Trumpet | Yellow | 47 |

| "Jetfire" | 6: Cyclamineus | Yellow–Orange | 42 |

| "Ice Follies" | 2: Large cup | White | 36 |

"Carlton" and "Ice Follies" (Division 2: Large cup) have a long history of cultivation, together with "Dutch Master" and "Golden Harvest" (1: yellow). "Carlton" and "Golden Harvest" were introduced in 1927, and "Ice Follies" in 1953. "Carlton", with over 9 billion bulbs (350 000 tons), is among the more numerous individual plants produced in the world.[202] The other major areas of production are the United States,[148] Israel which exported 25 million N. tazetta cultivar bulbs in 2003,[201] and the United Kingdom.

In the United Kingdom a total of 4100 ha were planted with bulbs, of which 3800 ha were Narcissi, the UK's most important bulb crop, much of which is for export,[203] making this the largest global production centre, about half of the total production area. While some of the production is for forcing, most is for dry bulb production. Bulb production and forcing occurs in the East, while production in the south west is mainly for outdoor flower production.[204] The farm gate value was estimated at £10m in 2007.[205]

Production of both bulbs and cut flowers takes place in open fields in beds or ridges, often in the same field, allowing adaptation to changing market conditions. Narcissi grow best in mild maritime climates. Compared to the United Kingdom, the harsher winters in the Netherlands require covering the fields with straw for protection. Areas with higher rainfall and temperatures are more susceptible to diseases that attack crops. Production is based on a 1 (UK) or 2 (Netherlands) year cycle. Optimal soil pH is 6.0–7.5. Prior to planting disinfection by hot water takes place, such as immersion at 44.4 °C for three hours.[140]

Bulbs are harvested for market in the summer, sorted, stored for 2–3 weeks, and then further disinfected by a hot (43.5 °C) bath. This eliminates infestations by narcissus fly and nematodes. The bulbs are then dried at a high temperature, and then stored at 15.5 °C.[4] The initiation of new flower development in the bulb takes place in late spring before the bulbs are lifted, and is completed by mid summer while the bulbs are in storage. The optimal temperature for initiation is 20 °C followed by cooling to 13 °C.[5]

Traditionally, sales took place in the daffodil fields prior to harvesting the bulbs, but today sales are handled by Marketing Boards although still before harvesting. In the Netherlands there are special exhibition gardens for major buyers to view flowers and order bulbs, some larger ones may have more than a thousand narcissus varieties on display. While individuals can visit these gardens they cannot buy bulbs at retail, which are only available at wholesale, usually at a minimum of several hundredweight. The most famous display is at Keukenhof, although only about 100 narcissus varieties are on display there.

Forcing

There is also a market for forced blooms, both as cut flowers and potted flowers through the winter from Christmas to Easter, the long season requiring special preparation by growers.

Cut flowers

For cut flowers, bulbs larger than 12 cm in size are preferred. To bloom in December, bulbs are harvested in June to July, dried, stored for four days at 34 °C, two weeks at 30 and two weeks at 17–20 °C and then placed in cold storage for precooling at 9 degrees for about 15–16 weeks. The bulbs are then planted in light compost in crates in a greenhouse for forcing at 13 °C–15 °C and the blooms appear in 19–30 days.[4][140]

Potted flowers

For potted flowers a lower temperature is used for precooling (5 °C for 15 weeks), followed by 16 °C–18 °C in a greenhouse. For later blooming (mid- and late-forcing), bulbs are harvested in July to August and the higher temperatures are omitted, being stored a 17–20 °C after harvesting and placed in cold storage at 9 °C in September for 17–18 (cut flowers) or 14–16 (potted flowers) weeks. The bulbs can then be planted in cold frames, and then forced in a greenhouse according to requirements.[140] N. tazetta and its cultivars are an exception to this rule, requiring no cold period. Often harvested in October, bulbs are lifted in May and dried and heated to 30 °C for three weeks, then stored at 25 °C for 12 weeks and planted. Flowering can be delayed by storing at 5 °C–10 °C.[111]

Culture

Symbols

The daffodil is the national flower of Wales, associated with Saint David's Day (March 1). The narcissus is also a national flower symbolising the new year or Nowruz in the Iranian culture.

In the West the narcissus is perceived as a symbol of vanity, in the East as a symbol of wealth and good fortune , while in Persian literature, the narcissus is a symbol of beautiful eyes.

In western countries the daffodil is also associated with spring festivals such as Lent and its successor Easter. In Germany the wild narcissus, N. pseudonarcissus, is known as the Osterglocke or "Easter bell." In the United Kingdom the daffodil is sometimes referred to as the Lenten lily.[91][92][Note 4]

Although prized as an ornamental flower, some people consider narcissi unlucky, because they hang their heads implying misfortune.[21] White narcissi, such as N triandrus "Thalia", are especially associated with death, and have been called grave flowers.[206][207] In Ancient Greece narcissi were planted near tombs, and Robert Herrick describes them as portents of death, an association which also appears in the myth of Persephone and the underworld .

Art

Antiquity

The decorative use of narcissi dates as far back as ancient Egyptian tombs, and frescoes at Pompeii.[208] They are mentioned in the King James Version of the Bible[209] as the Rose of Sharon[75][210][211][212] and make frequent appearances in classical literature.[164]

Greek culture

The narcissus appears in two Graeco-Roman myths, that of the youth Narcissus who was turned into the flower of that name, and of the Goddess Persephone snatched into the Underworld by the god Hades while picking the flowers. The narcissus is considered sacred to both Hades and Persephone,[213] and grows along the banks of the river Styx in the underworld.[207]

The Greek poet Stasinos mentioned them in the Cypria amongst the flowers of Cyprus.[214] The legend of Persephone comes to us mainly in the seventh century BC Homeric Hymn To Demeter,[215] where the author describes the narcissus, and its role as a lure to trap the young Persephone. The flower, she recounts to her mother was the last flower she reached for before being seized.

Other Greek authors making reference to the narcissus include Sophocles and Plutarch. Sophocles, in Oedipus at Colonus utilises narcissus in a symbolic manner, implying fertility,[216] allying it with the cults of Demeter and her daughter Kore (Persephone),[217] and by extension, a symbol of death.[218] Jebb comments that it is the flower of imminent death with its fragrance being narcotic, emphasised by its pale white colour. Just as Persephone reaching for the flower heralded her doom, the youth Narcissus gazing at his own reflection portended his own death.[217] Plutarch refers to this in his Symposiacs as numbing the nerves causing a heaviness in the limbs.[219] He refers to Sophocles' "crown of the great Goddesses", which is the source of the English phrase "Chaplet of the infernal Gods" incorrectly attributed to Socrates.[72]

A passage by Moschus, describes fragrant narcissi.[220][221][222] Homer in his Odyssey[223][224][225][226] described the underworld as having Elysian meadows carpeted with flowers, thought to be narcissus, as described by Theophrastus.[75][227][Note 5] A similar account is provided by Lucian describing the flowers in the underworld.[228][229][230] The myth of the youth Narcissus is also taken up by Pausanias. He believed that the myth of Persephone long antedated that of Narcissus, and hence discounted the idea the flower was named after the youth.[78]

Roman culture

Virgil, the first known Roman writer to refer to the narcissus, does so in several places, for instance twice in the Georgics.[231] Virgil refers to the cup shaped corona of the narcissus flower, allegedly containing the tears of the self-loving youth Narcissus.[232] Milton makes a similar analogy "And Daffodillies fill their Cups with Tears".[233] Virgil also mentions narcissi three times in the Eclogues.[234][235]

The poet Ovid also dealt with the mythology of the narcissus. In his Metamorphoses, he recounts the story of the youth Narcissus who, after his death, is turned into the flower,[236][237] and it is also mentioned in Book 5 of his poem Fasti.[238][239] This theme of metamorphosis was broader than just Narcissus; for instance see crocus, laurel and hyacinth.[240]

Western culture

William Wordsworth (1804 version)[241]

wandered lonely as a Cloud

That floats on high o'er Vales and Hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd

A host of dancing Daffodils;

Along the Lake, beneath the trees,

Ten thousand dancing in the breeze.

The waves beside them danced, but they

Outdid the sparkling waves in glee: –

A poet could not but be gay

In such a laughing company:

I gaz'd – and gaz'd – but little thought

What wealth the shew to me had brought:

For oft when on my couch I lie

In vacant or in pensive mood,

They flash upon that inward eye

Which is the bliss of solitude,

And then my heart with pleasure fills,

And dances with the Daffodils.

Although there is no clear evidence that the flower's name derives directly from the Greek myth, this link between the flower and the myth became firmly part of western culture. The narcissus or daffodil is the most loved of all English plants,[154] and appears frequently in English literature. Many English writers have referred to the cultural and symbolic importance of Narcissus[242][243][244][245]). No flower has received more poetic description except the rose and the lily, with poems by authors from John Gower, Shakespeare, Milton (see Roman culture, above), Wordsworth, Shelley and Keats. Frequently the poems deal with self-love derived from Ovid's account.[246][247] Gower's reference to the yellow flower of the legend has been assumed to be the daffodil or Narcissus,[248] though as with all references in the older literature to the flower that sprang from the youth's death, there is room for some debate as to the exact species of flower indicated, some preferring Crocus.[249] Spenser announces the coming of the Daffodil in Aprill of his Shepheardes Calender (1579).[250]

Shakespeare, who frequently uses flower imagery,[245] refers to daffodils twice in The Winter's Tale [251] and also The Two Noble Kinsmen. Robert Herrick alludes to their association with death in a number of poems.[252][253] Among the English romantic movement writers none is better known than William Wordsworth's short 1804 poem I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud[241] which has become linked in the popular mind with the daffodils that form its main image.[75][207][246][254] Wordsworth also included the daffodil in other poems.[255] Yet the description given of daffodils by his sister, Dorothy is just as poetic, if not more so,[170] just that her poetry was prose and appears almost an unconscious imitation of the first section of the Homeric Hymn to Demeter (see Greek culture, above).[256][170][257] Among their contemporaries, Keats refers to daffodils among those things capable of bringing "joy for ever".[258]

More recently A. E. Housman, using one of the daffodil's more symbolic names (see Symbols), wrote The Lent Lily in A Shropshire Lad, describing the traditional Easter death of the daffodil.[259]