| Cypro-Minoan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | Syllabary

|

Time period | c. 1550–1050 BC |

| Status | Extinct |

| Direction | left to right |

| Languages | unknown |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Linear A

|

Child systems | Cypriot syllabary |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Cpmn (402), Cypro-Minoan |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Cypro Minoan |

| U+12F90–U+12FFF | |

The Cypro-Minoan syllabary (CM) is an undeciphered syllabary used on the island of Cyprus during the late Bronze Age (c. 1550–1050 BC). The term "Cypro-Minoan" was coined by Arthur Evans in 1909 based on its visual similarity to Linear A on Minoan Crete, from which CM is thought to be derived.[1] Approximately 250 objects—such as clay balls, cylinders, and tablets and votive stands—which bear Cypro-Minoan inscriptions, have been found. Discoveries have been made at various sites around Cyprus, as well as in the ancient city of Ugarit on the Syrian coast.

Emergence

Little is known about how this script originated or about the underlying language. However, its use continued into the early Iron Age, forming a link to the Cypriot syllabary, which has been deciphered as Greek.

Arthur Evans considered the Cypro-Minoan syllabary to be a result of uninterrupted evolution of the Minoan Linear A script. He believed that the script was brought to Cyprus by Minoan colonizers or migrants. Evans' theory was uncritically supported until recently, when it was shown that the earliest Cypro-Minoan inscriptions were separated from the earliest texts in Linear A by less than a century, yet the Cypro-Minoan script at its earliest stage was substantially different from Linear A: it contained only syllabic signs while Linear A and its descendant Linear B both contained multiple ideograms, and its form was adapted to writing on clay while Linear A was better suited to writing with ink. The Linear B script that emerged a century later still retained many more features from, and most of the signary of, Linear A. All this evidence indicates a one-time introduction rather than long-time development.[2]

Varieties and periodization

The earliest inscriptions are dated about 1550 BC.

Although some scholars disagree with this classification,[3] the inscriptions have been classified by Emilia Masson into four closely related groups:[4] archaic CM, CM1 (also known as Linear C), CM2, and CM3, which she considered chronological stages of development of the writing. This classification was and is generally accepted, but in 2011 Silvia Ferrara contested its chronological nature based on the archaeological context. She pointed out that CM1, CM2, and CM3 all existed simultaneously, their texts demonstrated the same statistical and combinatorial regularities, and their character sets should have been basically the same; she also noted a strong correlation between these groups and the use of different writing materials. Only the archaic CM found in the earliest archaeological context is indeed distinct from these three.[2]

Spread and extinction

The Cypro-Minoan script was absent in some Bronze Age cities of Cyprus, yet abundant in others.

Unlike many other neighboring states, the Late Bronze Age collapse had only a slight impact on Bronze Age Cyprus; in fact, the island culture flourished in the period immediately following the dramatic events of the collapse, and there was a visible increase in the use of the script in such centers as Enkomi. On the other hand, as a direct result of this collapse, the script ceased to exist in Ugarit, along with Ugarit itself. After that point, the number of Greek artifacts gradually increased in the Cypriot context, and around 950 BC the Cypro-Minoan script suddenly disappears, being soon substituted by the new Cypriot syllabary, whose inscriptions represent mainly the Greek language, with just a few short texts in Eteocypriot.

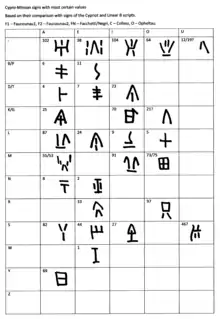

Language and cultural attribution

As long as the script remains undeciphered (with only about 15–20 signs having clear parallels in cognate scripts), it can only be speculated whether the language was the same as Minoan or Eteocypriot, and whether these two were identical or related. However, Silvia Ferrara and A. Bernard Knapp noted that the name "Cypro-Minoan" (based on the origin of the script) is rather deceptive, as the archaeological context of Cyprus was largely different from that of Minoan Crete, even in spite of visible traces of trade with Crete in the archaeological context, as well as the common presence of Cypriot and Cretan writing in Ugarit. There were no visible traces of Minoan invasion, colonization, or even significant cultural influence in Bronze Age Cyprus. At that time, the island was part of the Near-East cultural circle[2] rather than Aegean civilizations.

Based on the above-mentioned classification of the script into several varieties, Emilia Masson hypothesized that they may represent different languages that chronologically supplanted each other. Ferrara, while disproving Masson's hypothesis about these varieties as chronological stages, also indicated that the statistics of use of signs for all the varieties, as well as several noticeable combinations of signs, were the same for all the varieties, which may point to the same language rather than separate languages.

Artifacts

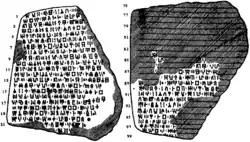

The earliest known CM inscription found in Europe was a clay tablet discovered in 1955 at the ancient site of Enkomi, near the east coast of Cyprus. It was dated to ca. 1500 BC, and bore three lines of writing.[5] Other fragments of clay tablets have been found at Enkomi and Ugarit. Three examples have emerged at Tiryns, a large jug (4 signs), a clay boule (3 signs), and a Canaanite amphora (2 signs).[6][7][8]

Clay balls

Dozens of small clay balls, each bearing 3–5 signs in CM1, have been uncovered at Enkomi and Kition.

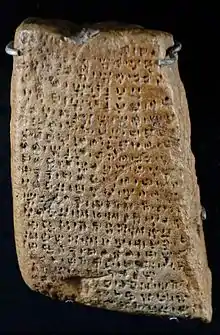

Clay cylinders

Clay cylinders have been uncovered at Enkomi and Kalavassos-Ayios Dimitrios, some of which bear lengthy texts (more than 100 characters). It is likely that the balls and cylinders are related to the keeping of economic records on Minoan Cyprus, considering the large number of cross-references between the texts.[9] The longest legible CM1 inscription is a cylinder found at Enkomi with 217 signs, dated to the 14th century BC.[10]

Stirrup cups

Cypro-Minoan signs were found on stirrup cups in Cannatello, Sicily.[11]

Decipherment

The extant corpus of Cypro-Minoan is not large enough to allow for the isolated use of a cryptographic solution to decipherment.[12] Currently, the total number of signs on formal Cypro-Minoan signs (approx. 2,500) compares unfavorably with the number known from the undeciphered Linear A signs (over 7,000) and the number available in Linear B when it was deciphered (approx. 30,000). Furthermore, different languages may have been represented by the same Cypro-Minoan subsystem, and without the discovery of bilingual texts or many more texts in each subsystem, decipherment is extremely unlikely.[13] According to Thomas G. Palaima, "all past and current schemes of decipherment of Cypro-Minoan are improbable".[3] Silvia Ferrara also believes this to be the case, as she concluded in her detailed analysis of the subject in 2012.[14]

Recent developments

Several attempts to decipher the script (Ernst Sittig, V. Sergeev, Jan Best etc.) were rejected by specialists due to numerous inaccuracies.

In 1998, Joanna S. Smith and Nicolle Hirschfeld received the 1998 Best of Show Poster Award at the annual meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America for their work on the Cypro-Minoan Corpus project, which aims to create a complete and accurate corpus of CM inscriptions, and archaeological and epigraphical discussions of all the evidence.[15] Jean-Pierre Olivier issued an edition in 2007 of all 217 of the inscriptions available to him.

Silvia Ferrara has prepared an even more comprehensive edition of the corpus as a companion volume to her analytic survey of 2012. In 2012–2013, Ferrara published two volumes of her research, where she studied the script in its archaeological context. It contained an additional 27 inscriptions. She also largely used statistical and combinatoric methods to study the structure of large texts and to detect regularities in the use of the signs. Her work is interesting for substantiated contesting of several important hypotheses largely accepted before, namely related to the emergence, chronological classification, language and "non-Minoan" attribution of the texts.[16]

Since then an additional 7 inscriptions have been published.[17]

In his 2016 PhD thesis, M.F.G. Valério produced a revised sign inventory and aimed to leverage previous hypotheses on decipherment and development of signs and values with a distributional analysis and comparative linguistic considerations. Unlike most other approaches on decipherment, he assumes a single script applied to a potentially broader range of languages, including Semitic (in Ugarit) and the indigenous language(s) of Cyprus. For the latter, he discusses a potential relationship with the Eteocypriot language, based on his readings.[18]

Unicode

Cypro-Minoan was added to the Unicode Standard in September 2021, with the release of version 14.0.

The Unicode block for Cypro-Minoan is U+12F90–U+12FFF:

| Cypro-Minoan[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+12F9x | 𒾐 | 𒾑 | 𒾒 | 𒾓 | 𒾔 | 𒾕 | 𒾖 | 𒾗 | 𒾘 | 𒾙 | 𒾚 | 𒾛 | 𒾜 | 𒾝 | 𒾞 | 𒾟 |

| U+12FAx | 𒾠 | 𒾡 | 𒾢 | 𒾣 | 𒾤 | 𒾥 | 𒾦 | 𒾧 | 𒾨 | 𒾩 | 𒾪 | 𒾫 | 𒾬 | 𒾭 | 𒾮 | 𒾯 |

| U+12FBx | 𒾰 | 𒾱 | 𒾲 | 𒾳 | 𒾴 | 𒾵 | 𒾶 | 𒾷 | 𒾸 | 𒾹 | 𒾺 | 𒾻 | 𒾼 | 𒾽 | 𒾾 | 𒾿 |

| U+12FCx | 𒿀 | 𒿁 | 𒿂 | 𒿃 | 𒿄 | 𒿅 | 𒿆 | 𒿇 | 𒿈 | 𒿉 | 𒿊 | 𒿋 | 𒿌 | 𒿍 | 𒿎 | 𒿏 |

| U+12FDx | 𒿐 | 𒿑 | 𒿒 | 𒿓 | 𒿔 | 𒿕 | 𒿖 | 𒿗 | 𒿘 | 𒿙 | 𒿚 | 𒿛 | 𒿜 | 𒿝 | 𒿞 | 𒿟 |

| U+12FEx | 𒿠 | 𒿡 | 𒿢 | 𒿣 | 𒿤 | 𒿥 | 𒿦 | 𒿧 | 𒿨 | 𒿩 | 𒿪 | 𒿫 | 𒿬 | 𒿭 | 𒿮 | 𒿯 |

| U+12FFx | 𒿰 | 𒿱 | 𒿲 | |||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- ↑ Palaima 1989.

- 1 2 3 Ferrara, 2012, vol. 1

- 1 2 Palaima 1989, p. 121.

- ↑ Masson 1971.

- ↑ Chadwick 1987, pp. 50–52.

- ↑ Davis, Brent, Maran, Joseph and Wirghová, Soňa. "A new Cypro-Minoan inscription from Tiryns: TIRY Avas 002" Kadmos, vol. 53, no. 1-2, 2014, pp. 91–109

- ↑ Vetters, M. 2011. A Clay Ball with a Cypro-Minoan Inscription from Tiryns, Archäologischer Anzeiger 2011.2, pp. 1–49

- ↑ Kilian, K. 1988. Ausgrabungen in Tiryns 1982/83: Bericht zu den Grabungen, Archäologischer Anzeiger 1988, pp 105–151

- ↑ Woudhuizen 1992, p. 82.

- ↑ Janko, Richard. "Eteocypriot in the Bronze Age? The Cypro-Minoan cylinder from Enkomi as an accounting document" Kadmos, vol. 59, no. 1-2, 2020, pp. 43–61

- ↑ Day, P. M., & Joyner, L. (2005). Coarseware Stirrup Jars from Cannatello, Sicily: New Evidence from Petrographic Analysis, Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici47, pp. 309–31

- ↑ Billigmeier, Jon C. “Toward a Decipherment of Cypro-Minoan.” American Journal of Archaeology, vol. 80, no. 3, 1976, pp. 295–300

- ↑ Palaima 1989, p. 123.

- ↑ Ferrara, Silvia (2012). Cypro-Minoan Inscriptions: Volume I: Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 271–274. ISBN 978-0-19-960757-0.

- ↑ CAARI News p. 5.

- ↑ Steele, Philippa M.. "Distinguishing between Cypriot scripts: Steps towards establishing a methodology" Kadmos, vol. 53, no. 1-2, 2014, pp. 129–148

- ↑ Valério, Miguel. "Seven uncollected Cypro-Minoan inscriptions" Kadmos, vol. 53, no. 1-2, 2014, pp. 111–127

- ↑ Valério, Miguel Filipe Grandão (2016). Investigating the Signs and Sounds of Cypro-Minoan. PhD thesis, Universitat de Barcelona.

Sources

- Benson, J. L. and Masson, O. 1960. Cypro-Minoan Inscriptions from Bamboula, Kourion: General Remarks and New Documents, American Journal of Archaeology 64/2, pp. 145–151

- Best, Jan; Woudhuizen, Fred (1988). Ancient Scripts from Crete and Cyprus. Leiden: E.J. Brill. pp. 98–131. ISBN 90-04-08431-2.

- Chadwick, John (1987). Linear B and Related Scripts. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 50–56. ISBN 0-520-06019-9.

- Cross, F. M. and Stager, L. E. 2006. Cypro-Minoan Inscriptions Found in Ashkelon, Israel Exploration Journal 56/2, pp. 129–159

- Facchetti, G. & Negri, M. (2014), Riflessioni preliminary sul ciprominoico. Do-so-mo 10, p. 9–25.

- Fauconau, J. (1977), Études chypro-minoennes. Syria 54(3/4), pp. 209–249.

- Fauconau, J. (1980), Études chypro-minoennes. Syria 54(2/4), pp. 375–410.

- Faucounau, J. (1994), The Cypro-Minoan scripts: a reappraisal fifty years after John F. Daniel's paper. Κυπριακή Αρχαιολογία Τόμος ΙΙI (Archaeologia Cypria, Volume III), p. 93–106.

- Faucounau, Jean (2007). Les Inscriptions Chypro-Minoennes I. Paris: Editions L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-296-04862-1.

- Faucounau, Jean (2008). Les Inscriptions Chypro-Minoennes II. Paris: Editions L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-296-06006-7.

- Ferrara, Silvia, Cypro-Minoan Inscriptions. Vol. 1: Analysis (2012); Vol. 2: The Corpus (2013). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-960757-5 and ISBN 0-19-969382-X

- Masson, Emilia (1971). Studies in Cypro-Minoan Scripts. Part 1. Göteborg: Astrom Editions. ISBN 978-91-85058-42-6.

- Nahm, Werner (1981). "Studien zur kypro-minoischen Schrift", Kadmos 20 (1981) 52-63; Kadmos 23, 164-179.

- Olivier, Jean-Pierre (2007), Edition Holistique des Textes Chypro-Minoens, Fabrizio Serra Editore, Pisa-Roma, ISBN 88-6227-031-3

- "CAARI News Number 18" (PDF). Cyprus American Archaeological Research Institute. June 1999. p. 5. Retrieved 2009-05-09.

- Palaima, Thomas G. (1989). "Cypro-Minoan Scripts: Problems of Historical Context". In Duhoux, Yves; Palaima, Thomas G.; Bennet, John (eds.). Problems in Decipherment. Louvain-La-Neuve: Peeters. pp. 121–188. ISBN 90-6831-177-8.

- Steele, P. M. (2013), A linguistic history of ancient Cyprus. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 1-107-04286-0 (hard) and ISBN 1-107-61741-3 (soft)

- Steele, Philippa M. (Ed.) (2013), Syllabic Writing on Cyprus and its Context, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 1-107-02671-7

- Woudhuizen, Fred (1992). The Language of the Sea Peoples. Amsterdam: Najade Press. pp. 81–153. ISBN 90-73835-02-X.

- Duhoux, Yves, "Eteocypriot and Cypro-Minoan 1–3", in: Kadmos 48, 2000, pp. 39-75, doi:10.1515.