The culture of the Maldives is derived from a number of sources, the most important of which is its proximity to the shores of Sri Lanka and South India. The population is mainly Indo-Aryan from the anthropological point of view. Islam is considered the religion of the country and only Muslims can become legal citizens.

Influences

The Dhivehi language is of Indo-Iranian Sanskritic origin and therefore closely related to Sinhala, which points at a later influence from the north of the subcontinent. According to legends, the kingly dynasty that ruled the Maldives in the past has its origin there.

These ancient kings may have brought Buddhism from the subcontinent, but it is not clear. In Sri Lanka, there are similar legends, but it is improbable that the ancient Maldives royals and Buddhism came both from that island, because none of the Sri Lankan chronicles mentions the Maldives. It is unlikely that the ancient chronicles of Sri Lanka would have failed to mention the Maldives, if a branch of its kingdom had extended itself to the Maldive Islands.

Since the 12th century AD, there have also been influences from Arabia in the language and culture of the Maldives, because of the general conversion to Islam at that time, and its location as a crossroads in the central Indian Ocean.

In the islands' culture, there are a few elements of African origin as well, from slaves brought to the court by the Royal family and nobles from their Hajj journeys to Arabia in the past. There are islands like Feridhu and Maalhos in Northern Ari Atoll, and Goidhu in Southern Maalhosmadulhu Atoll where many of the inhabitants trace their ancestry to released African slaves.[1]

Society

The status of women in the Maldives was traditionally fairly high, as attested to in part by the existence of four Sultanas. Women typically wear the veil, but are not required to do so by law nor are they strictly secluded. Special sections are reserved for women in public places, such as stadiums and mosques. Women do not accept their husbands' names after marriage but maintain their maiden names. Inheritance of property is through both males and females.

Women have always had an important role in the family and community. In the early history of Maldives, it was not uncommon to have a woman as a Sultana or ruler and it has been suggested that Maldivian society was once a matriarchy. In today's society women hold strong positions in government and business. A large percentage of government employees are women. The male-to-female ratio of enrollment and completion of education to secondary school standards remains equivalent. Women serve in both the cabinet and the Parliament.

Maldivian culture shares many aspects of a strong matriarchal tradition with ancient Dravidian culture. A unique feature of Maldivian society is a very high divorce rate, which has been attributed by some as due to early marriage. Others have seen this extremely high divorce rate as reflecting the combination of liberal Islamic rules about divorce and the relatively loose marital bonds that may be produced by the lack of a history of fully developed agriculture and the accompanying codes of agrarian honor and property relations.[2]

Polygamy in the Maldives is legal, though such unions have been reported to be very uncommon. Even so, fifty-nine polygamous marriages took place in 1998.[3] Polygamy is also specifically covered by a 2001 Maldivian law, which orders courts to assess a man's finances before letting him take another wife.[4]

Prostitution in the Maldives is illegal and foreigners who engage in prostitution can expect to be deported and Maldivians can expect a prison sentence.[5][6]

Homosexuality in the Maldives was criminalised in the 1880s.[7]

Public holidays in the Maldives include both civilian dates and Islamic religious holidays.[8]

- Family life

Judaage Aminat Didi in 1982, wearing the simple customary libaas worn by all southern Maldivian women before the modern islamification promoted by President Maumoon. First "burugaa" headscarf reached Fuvahmulah only in 1989.

Judaage Aminat Didi in 1982, wearing the simple customary libaas worn by all southern Maldivian women before the modern islamification promoted by President Maumoon. First "burugaa" headscarf reached Fuvahmulah only in 1989. Kashimaage Hakimatu, daughter of an excellent master carpenter boatbuilder, 1983. Fuvahmulah Island

Kashimaage Hakimatu, daughter of an excellent master carpenter boatbuilder, 1983. Fuvahmulah Island Gage Naima dancing while she was a girl at the Royal Court in Male. Based on a picture taken around 1960.

Gage Naima dancing while she was a girl at the Royal Court in Male. Based on a picture taken around 1960. A baby sleeping on a swingbed. The duty of the older siblings is to keep it swinging. 1980

A baby sleeping on a swingbed. The duty of the older siblings is to keep it swinging. 1980 Woman rocking a traditional Maldivian swingbed (un'dholi) holding a baby in local fashion.

Woman rocking a traditional Maldivian swingbed (un'dholi) holding a baby in local fashion.

Cuisine

The cuisine of Maldives is mainly fish as the fishing industry is the second-largest industry in the country. Daily meals include rice and fish, the most common foods, with fish being the most important source of protein in the average diet. In the past very few vegetables were eaten due to a lack of farming land in the country. Most food served in tourist resorts is imported. On ceremonial occasions, meat other than pork is eaten. Alcohol is not permitted except at tourist resorts. Basic commodities such as rice, sugar, and flour are imported. A popular Maldivian dish is garudhiya, a fish broth with rice, typically eaten with rice, fried or grilled fish, chili pepper, lime, onions, garlic and theluli faiy (fried monringa leaves).[9] In addition to this, people in the Maldives eat roshi (flatbread) with different types of curry.

Arts

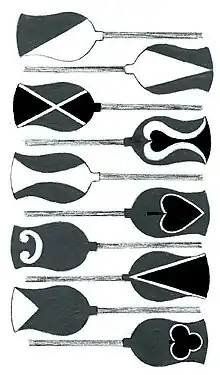

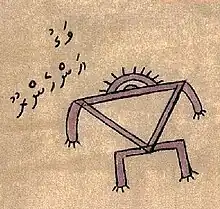

- Fish drawings from astrology books, Fuvahmulah

Crafts

The Maldives holds a rich art and craft heritage such as Mat weaving, rope weaving etc.

Top of a malaafaiy (wooden cover for food items) with Arabic writing. Lacquered wood made in Thulhaadhoo Island, 1985.

Top of a malaafaiy (wooden cover for food items) with Arabic writing. Lacquered wood made in Thulhaadhoo Island, 1985. Quality Mat from Gaddhu, Huvadhu atoll

Quality Mat from Gaddhu, Huvadhu atoll

Sailing

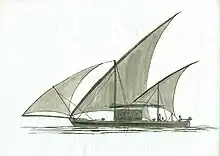

Naalu battheli, a Maldive fishing sailboat transformed into a temporary trading boat.

Naalu battheli, a Maldive fishing sailboat transformed into a temporary trading boat. Hafali doni. A six-oared fishing boat with a detachable mast and a square sail. Fuvahmulah, 1982.

Hafali doni. A six-oared fishing boat with a detachable mast and a square sail. Fuvahmulah, 1982. Ready for the journey. Goods on the beach prepared to be loaded on the boat. The bundle of the trader's bedding is on top of the heap. Fuvahmulah, 1981.

Ready for the journey. Goods on the beach prepared to be loaded on the boat. The bundle of the trader's bedding is on top of the heap. Fuvahmulah, 1981. Loading goods on a boat bound for the capital. Fuvahmulah, 1981.

Loading goods on a boat bound for the capital. Fuvahmulah, 1981. Boat arrival in Fuvahmulah, 1982

Boat arrival in Fuvahmulah, 1982

Folklore

The Maldivian folklore is the body of myths, tales and anecdotes belonging to the oral tradition of Maldivians. Even though some of the Maldivian myths were already mentioned briefly by British commissioner in Ceylon HCP Bell towards the end of the 19th century,[10] their study and publication were carried out only quite recently by Spanish writer and artist Xavier Romero-Frias, at a time when that ancestral worldview was quickly disappearing.[11]

Be. Popular celebration in Holhudu Island. Men dressed like evil spirits walk around the island scaring the children.

Be. Popular celebration in Holhudu Island. Men dressed like evil spirits walk around the island scaring the children. Be. Popular celebration in Holhudu Island. Men dressed like evil spirits beat empty bandiyaa water pots in the night.

Be. Popular celebration in Holhudu Island. Men dressed like evil spirits beat empty bandiyaa water pots in the night.

Music and dance

Culturally, Maldivians feel some affinity to Northern India through their language, which is related to the languages of North India. Most older generation Maldivians like to watch Hindi movies and listen to Hindi songs. Many popular Maldivian songs are based on Hindi tunes. The reason is that out of a similar language, similar rhythms and cadences develop. In fact, it is very easy for Maldivians to fit local lyrics to a Hindi song. Bollywood songs are among the most popular songs in Maldives, especially the old ones from Mohammad Rafi, Mukesh, Lata Mangeshkar, and Asha Bhonsle. Therefore, most local Maldivian dances and songs are based in (or influenced by) North Indian Kathak dances and Hindi songs.

The favourite musical instrument of Maldivians is the bulbul tarang, a kind of horizontal accordion. This instrument is also used to accompany devotional songs, like Maulūd and Maadhaha. The Bodu Beru (literally "Big Drum") drumming performances are said to have African roots.

Gaa odi lava. Popular celebration in Holhudu Island. Dance performed by men, 1991.

Gaa odi lava. Popular celebration in Holhudu Island. Dance performed by men, 1991. Every year peoples of Fuvahmulah Celebrate Maahefun at Fuvahmulah Thoondu area which is the north beach of Fuvahmulah

Every year peoples of Fuvahmulah Celebrate Maahefun at Fuvahmulah Thoondu area which is the north beach of Fuvahmulah Every year peoples of Fuvahmulah Celebrate Maahefun at Fuvahmulah Thoondu area which is the north beach of Fuvahmulah

Every year peoples of Fuvahmulah Celebrate Maahefun at Fuvahmulah Thoondu area which is the north beach of Fuvahmulah Maahefun Festival in Fuvahmulah was held on July 31, 2011, with more than 4000 people from Fuvahmulah and other islands of Maldives.

Maahefun Festival in Fuvahmulah was held on July 31, 2011, with more than 4000 people from Fuvahmulah and other islands of Maldives.

See also

References

- ↑ Xavier Romero-Frias, The Maldive Islanders, A Study of the Popular Culture of an Ancient Ocean Kingdom. Barcelona 1999, ISBN 84-7254-801-5

- ↑ Marcus, Anthony. 2012. “Reconsidering Talaq: Marriage, Divorce and Sharia Reform in the Republic of Maldives” in Chitra Raghavan and James Levine. Self-Determination and Women’s Rights in Muslim Societies. Lebanon, NH: Brandeis University Press Archived 2017-10-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Maldives: Gender and Development Assessment Archived 2012-04-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Maldives divorce rate soars

- ↑ "Prostitution on the rise in the Maldives". Minivan Daily. Archived from the original on 2012-03-12. Retrieved 2011-09-18.

- ↑ "Maldives nab foreigners for prostitution". Lanka Business Online. Archived from the original on 2012-03-23. Retrieved 2011-09-18.

- ↑ "Where is it illegal to be gay?". BBC News. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ↑ List

- ↑ "How to lunch like a true Maldivian – Rice and Garudhiya". timesofaddu.com. Retrieved 27 July 2023.

- ↑ HCP Bell, The Máldive Islands: An account of the Physical Features, History, Inhabitants, Productions and Trade. Colombo, 1883

- ↑ Xavier Romero-Frias, The Maldive Islanders, A Study of the Popular Culture of an Ancient Ocean Kingdom, Barcelona 1999, ISBN 84-7254-801-5

- Divehiraajjege Jōgrafīge Vanavaru. Muhammadu Ibrahim Lutfee. G.Sōsanī. Male' 1999.

- HCP Bell, The Maldive Islands, An account of the physical features, History, Inhabitants, Productions and Trade. Colombo 1883, ISBN 81-206-1222-1

- Xavier Romero-Frias, The Maldive Islanders, A Study of the Popular Culture of an Ancient Ocean Kingdom. Barcelona 1999, ISBN 84-7254-801-5

- Divehi Tārīkhah Au Alikameh. Divehi Bahāi Tārikhah Khidmaiykurā Qaumī Markazu. Reprint 1958 edn. Male’ 1990.