| History of Cuba |

|---|

|

| Governorate of Cuba (1511–1519) |

| Viceroyalty of New Spain (1535–1821) |

|

| Captaincy General of Cuba (1607–1898) |

|

| US Military Government (1898–1902) |

|

| Republic of Cuba (1902–1959) |

|

| Republic of Cuba (1959–) |

|

| Timeline |

|

|

| Topical |

|

|

| Military of Cuba |

|---|

|

| Branches |

| Related articles |

The military history of Cuba is an aspect of the history of Cuba that spans several hundred years and encompasses the armed actions of Spanish Cuba while it was part of the Spanish Empire and the succeeding Cuban republics.

From the 16th to 18th centuries, organized militia companies made up the bulk of Cuba's armed forces. These forces helped maintain the territorial integrity of Spanish Cuba, and later, assisted the Spanish Army in its expeditionary action throughout North America. These forces were later supplanted by Spanish regulars in the 19th century, with Cuba being used as a major base of operations for Spain during the Spanish American wars of independence.

The latter half of the 19th century saw three Cuban wars of independence launched against the Spanish colonial government. The final conflict for independence escalated to the Spanish–American War and resulted in the American occupation of Cuba from 1898 to 1902.

After the Cuban Revolution in 1959 and communist takeover by Fidel Castro, Cuba became involved in several Cold War conflicts in Africa and the Middle East, where it supported Marxist governments and fought against Western proxies. Castro's Cuba had some 39,000–40,000 military personnel abroad by the late 1970s, with the bulk of the forces in Sub-Saharan Africa but with some 1,365 stationed in the Middle East and North Africa.[1] Cuban forces in Africa were mainly black and mulatto (mixed-race Spanish/African).[2] The loss of East European subsidies at the end of the Cold War weakened the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces.

16th and 17th centuries

Due to its strategic location along the Europe-Americas trade route, Spanish Cuba served as a crucial gateway to the Caribbean. Consequently, Cuba faced attacks from Spain's major colonial rivals to seize the "gateway", with attempts to seize control intensifying from the mid-16th century onward. In addition to other colonial rivals, the relatively undefended coastline resulted in privateers and pirates to raid the colony as well.[3]

Spanish territories in the Caribbean, including Cuba, relied on private individuals to preserve the internal peace and defend the colony's territorial integrity. These individuals initially came from privately financed conquistador armies, followed by organizations of volunteer troops and locally organized militia companies among the settlers at the end of the 16th century. Recognizing the vital role played by volunteer civilian militias in safeguarding its colonies, Spanish authorities in Cuba went out of their way to guarantee free white colonists and the free Black and multiracial population the right to bear arms.[3]

The first formal militia companies were organized in 1586, responding to the threat against English privateers.[3] From the 16th to the end of the 18th century, organized civilian militias formed the bulk of the Spanish Empire's fighting force in Cuba,[3] with the number of permanent militia companies in Cuba having increased in the late 17th century to match the number of attacks on the colony.[3]

Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604)

The Anglo-Spanish War (1585–1604) was an intermittent undeclared war between England and Spain, marked by naval engagements and military campaigns in Europe and the Americas, including the blockade of Western Cuba by English privateers in 1591.[4] In March 1596, a naval engagement occurred in Cuban waters between Spanish and English forces, where a squadron of 13 Spanish galleons intercepted an English squadron of 14 ships resupplying at Isla de la Juventud in Cuba. As a result of that battle, the Spanish squadron captured an English vessel with 300 sailors, and its captives were forced to work on Havana's defensive structures.[5]

Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War was an intermittent conflict between the rebels in the Spanish Netherlands (later the Dutch Republic), and the Spanish Empire. In 1628, the Dutch West India Company sent a fleet of 30 ships, commanded by Piet Pieterszoon Hein, to capture the Spanish treasure fleets. Having been made aware of the Dutch fleet, the treasure fleet initially remained in port at Cartagena and Veracruz. However, the treasure fleet later set sail, after Spanish authorities mistook the movement of a few Dutch ships back to Europe for the entirety of Hein's fleet.[6] Hein's fleet waited nearby Havana for the treasure fleet to arrive, as the ships from South America and Mexico typically rendezvous at that city before crossing the Atlantic Ocean.[7]

The treasure fleet was intercepted on 8 September at the Battle in the Bay of Matanzas. The Spanish galleons escorting the fleet abandoned the merchantmen capture, instead seeking refuge at bay of Matanzas. However, all four galleons ran aground as they were too laden with cargo and passengers, and were forced to surrender. The Dutch seized over 90 tonnes of gold and silver, valued at 11.5 million guilders.[7] The incident remained the only time an entire treasure fleet's cargo was taken.[6]

18th century

Cuba's militia system was expanded during the 18th century, growing from one company in 1600 to three full batallions and 16 separate companies by 1770.[8] Several Cuban militia units partook in military campaigns beyond the confines of Cuba during the 18th century.[9]

Auxillary labour battalions manned by Black slaves were also formed to augment Cuban forces. Slaves were initially pressed into service only for construction work, although by 1765, select slaves were also pressed into service with the artillery corps.[8]

War of Jenkin's Ear

The War of Jenkin's Ear was a conflict between the British and Spanish and was the first major European war to be fought expressively for Caribbean aims, with both colonial powers looking to secure their trade routes in the Caribbean. Early in the conflict, British forces in Jamaica concentrated their attacks on the Spanish Main instead of Cuba, as Havana lay too far windward from Jamaica to attack quickly and return in the shortest time possible.[10] Although the Spanish Havana squadron was reinforced at the onset of the conflict, the sizable British force in the Caribbean forced the Spanish to maintain a defensive posture in the region.[11]

In July 1741, British forces seized Guantánamo Bay largely unopposed, in preparation for their attack on Santiago de Cuba.[12] British attempts to invade Cuba from the bay failed, and its forces were withdrawn from Guantánamo by December.[12] Spain's military situation in the Caribbean improved as the failed British attacks on Guantánamo and Panama had effectively weakened the British position in the region, and the subsumption of the conflict into the wider War of the Austrian Succession had shifted British focus to Europe.[12] From 1741 to 1748, the Havana squadron's primary responsibility was the protection of the Spanish treasure fleet that sailed from Havana, with the defence of the Cuban coast and harassment of British privateers and illicit traders being a secondary concern.[13][14] Although the Havana squadron had rarely left its port after 1741, it had effectively become a fleet in being, threatening British convoys in the Straits of Florida and preventing any potential offensive operations against the French colony of Saint-Domingue.[15]

_-_Sir_Charles_Knowles's_Engagement_with_the_Spanish_Fleet_off_Havana._-_RCIN_406654_-_Royal_Collection.jpg.webp)

The British squadron in Jamaica resumed its offensive operations shortly after the arrival of Sir Charles Knowles in January 1748. His squadron attacked Santiago de Cuba in April 1748, although withdrew after experiencing some resistance. Anticipating the departure of Spanish treasure ships from Veracruz to Havana, Knowles mobilized all available forces in Jamaica to capture these ships. The commander of the Havana squadron, Andrés Reggio, initially sailed to intercept them but later ordered a return to port due to the enemy's superior numbers.[16] On their return, the Havana squadron encountered a British convoy and gave chase, although one British escort broke off from the convoy to alert Knowles of their location. On 12 October, near Havana, the Spanish and British squadrons clashed until the Spanish were compelled to withdraw. British forces pursued the Havana squadron's flagship until 15 October, when the British anchored just outside Havana Harbour. The following day, Spanish officials notified Knowles of a preliminary peace agreement between Britain and Spain, and that all hostilities were to cease immediately.[17]

Seven Years' War

In August 1761, Spain and France entered into the Third Bourbon Family Compact, where the former agreed to enter the Seven Years' War on the side of the latter by May 1762. War between the British and Spanish ensued in January 1762 when Spain disregarded a British ultimatum to abandon its commitment to the Bourbon Compact. Facing financial strain from its ongoing war with France and support for Prussia, the British, recognized the impracticality of prolonged conflict with the Spanish Empire and instead opted to capture Havana in Cuba and Manila in the Philippines to deliver a "decisive blow" against Spain's trading economy and force them to negotiate for peace.[18]

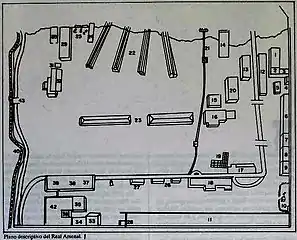

Havana was chosen as the target for the attack due to its significance as a rendezvous point for the Spanish treasure fleet and because of its military infrastructure, including the Royal Shipyard of Havana—one of three pivotal naval shipbuilding and repair yards Spain possesses in the region. The British set sail for Havana on 26 May 1762, with the invasion fleet capturing four Spanish naval vessels at the Old Bahama Channel on 2 June.[18]

The siege of Havana began on 6 June, with the city being defended by a 4.8-kilometre-long (3 mi) circuit wall and forts spread throughout it and manned by Spanish regulars and Cuban militiamen, while the harbour itself was protected by Spanish ships anchored within. Throughout the siege, British forces were reinforced by garrisoned soldiers from North America. By August, Havana's defenders faced a shortage of manpower and ammunition needed to prolong the siege. Don Juan de Prado, the captain-general of Cuba, surrendered Havana to the British on 13 August, beginning an 11-month occupation. Havana, along with Manila, was returned at the end of the war in 1763, with the signing of the Treaty of Paris.

As a result of the peace, Spain was forced to cede Spanish Florida to the British, although received the Louisiana territory of New France as compensation.[18] In the years after the war, several Native American delegations from Florida sought assistance from Spanish officials in Cuba to support their war effort against British colonists. However, these requests were refused by Spanish officials in Cuba, as they lacked the authority to fulfill these requests and would have been unable to provide any support against the British due to the recent peace treaty.[19]

Louisiana Rebellion

Tensions between dissenting French Creoles in Louisiana against the newly appointed Spanish governor, Antonio de Ulloa, took place in the years after the territory was handed over to the French, and a petition for Ulloa's expulsion was made after he introduced restrictive trade regulations. Nicolas Chauvin de La Frénière, the territory's attorney general, played a crucial role in rallying French Creole merchants against Spain's trade restrictions.

The Spanish government, with consent from the French royal court, sent General Alejandro O'Reilly to suppress the rebellion. O'Reilly arrived in 1769 with a force of nearly 2,000 men, including 240 Cuban militiamen.[8] O'Reilly's force took control of New Orleans without bloodshed and executed Lafrénière and his coconspirators. O'Reilly then proceeded to institute several changes, including new trade restrictions that made Havana the chief entrepôt for Spanish and French traders in New Orleans and effectively made the governor of Louisiana dependent on Cuba.

American Revolutionary War

During the first few years of the American Revolutionary War, the Spanish Empire used Havana as a port to support American revolutionaries, with Spanish authorities granting merchants and vessels associated with the revolution access to Havana's trade and treating them as a "most favoured nation". As Cuba had a substantial supply of Mexican silver on hand, typically used to subsidize the island's administrative and military expenses, the Spanish government authorized the transfer of this silver from Havana to the revolutionaries to help finance their war.[19]

Spain formally entered the conflict against the British in 1779, after the enactment of the Treaty of Aranjuez. Cuban soldiers fought alongside Mexicans, Spaniards, Puerto Ricans, and Dominicans under General Bernardo de Gálvez' command as far north as present-day Michigan.[20] Cuban militias later took part in the capture of the Bahamas during the twilight of the conflict in 1783, with the Spanish attacking the Bahamas in a bid to gain some territorial concessions from the British during peace negotiations.[19]

The resulting conflict led to the growth of Cuban-US trade relations, although trade between the emerging American republic and Cuba ceased for a brief period after the war between 1783 to 1789, owing to Spanish officials' apprehension towards the growth in Cuban-US trading relations during the war and the perceived threat of the United States against Spain's territorial holdings in North America.[19]

19th century

During the Spanish American wars of independence, a significant number of Spanish soldiers were based in Cuba, with the colony being transformed into a hub for Spanish counterrevolutionary operations.[21] A large Spanish garrison of 15,000 to 20,000 soldiers was maintained in Cuba following the end of the Spanish American wars for independence.[22]

As a result of the wars of independence throughout Spanish America, Cuba's organized militia companies experienced a decline throughout the 19th century. By 1830, soldiers from Spain made up the majority of Cuba's armed battalions.[21] The establishment of a paid insular police force in 1851, akin to the Spanish Civil Guard, further reduced the importance of the militia.[23] Although Cuban-based units were less prominent in the 19th century, several Cuban military units still saw overseas service, with Cuban regiments sent to the Dominican Republic to support the Spanish occupation of that country in 1861.[24] However, by the onset of the Ten Years' War, the militia no longer played a significant role in the armies of the Cuban royal government, with many of these militiamen forming the bulk of revolutionary armies.[25]

Ten Years' War

The Ten Years' War (1868–78) was the first of three wars that Cuba fought against Spain for its independence. The Ten Years' War began when Carlos Manuel de Céspedes and his followers of patriots from his sugar mill La Demajagua began an uprising. Dominican exiles, including Máximo Gómez, Luis Marcano and Modesto Díaz, joined the new Revolutionary Army and provided its initial training and leadership.[26] With reinforcements and guidance from the Dominicans, the Cuban rebels defeated Spanish detachments, cut railway lines, and gained dominance over vast sections of the eastern portion of the island.[27] On 19 February 1874, Gómez and 700 other rebels marched westward from their eastern base and defeated 2,000 Spanish troops at El Naranjo. The Spaniards lost 100 killed and 200 wounded and the rebels a total of 150 killed and wounded. The most significant rebel victory came at the Battle of Las Guasimas, which took place from 16–20 March 1874. During the battle, 2,050 rebels, led by Antonio Maceo and Gómez, defeated 5,000 Spanish troops with 6 cannons. The five-day battle cost the Spanish 1,037 casualties and the rebels 174 casualties.[26]

The Spanish built a fortified line (La Trocha) to prevent Gómez to move westward from Oriente province;[28] it consisted of numerous small forts, wire fences and a parallel railroad line. It was the largest Spanish fortification in the New World.[29] Gómez began an invasion of Western Cuba in 1875; he burned 83 plantations around Sancti Spíritus within a six-week period and freed their slaves.[26] However, the vast majority of slaves and wealthy sugar producers in the region did not join the revolt. After his most trusted general, the American Henry Reeve, was killed in 1876, the invasion was over. The war ended with the signing of the Pact of Zanjón. The Spanish lost 27,000 troops in battle and another 54,000 dead from disease.[30] The rebels sustained 40,000 dead and the island sustained over $300 million in property damage.[26]

Little War

The Little War (1879–1889) was the second of three conflicts between Cuban rebels and Spanish forces.

Cuban War of Independence

The Cuban War of Independence (1895–1898) was the last major uprising by Cuban Nationalists against the Spanish Colonial Government. The conflict culminated with American intervention during the Spanish–American War.

Spanish–American War

.jpg.webp)

The Spanish–American War in 1898 was a major war fought by the United States and the Kingdom of Spain in the Spanish territories of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines. The war was triggered with the sinking of the USS Maine in Havana Harbour. Cuban rebels fought alongside American troops throughout the war on the Cuban island. The war lasted for 10 weeks.

From 22–24 June, the U.S. V Corps under General William R. Shafter landed at Daiquirí and Siboney, east of Santiago, and established an American base of operations. A contingent of Spanish troops, having fought a skirmish with the Americans near Siboney on 23 June, had retired to their lightly entrenched positions at Las Guasimas. An advance guard of U.S. forces under former Confederate General Joseph Wheeler ignored Cuban scouting parties and orders to proceed with caution. They caught up with and engaged the Spanish rearguard of 1,500 soldiers led by General Antero Rubín who effectively ambushed them, in the Battle of Las Guasimas on 24 June. The Americans lost 16 killed and 52 wounded. The Spanish lost 12 dead and 24 wounded. On 1 July, a force of 15,065 American troops in regular infantry and cavalry regiments attacked 1,320 entrenched Spaniards in dangerous Civil War-style frontal assaults at the Battle of El Caney and Battle of San Juan Hill outside of Santiago, which cost the Americans 225 killed in action, 1,384 wounded in action, and 72 missing in action. At all battle sites on 1 July, the Spanish lost 215 killed, 376 wounded, and 200 captured.

After the battles of San Juan Hill and El Caney, the American advance halted. Spanish troops successfully defended Fort Canosa, allowing them to stabilize their line and bar the entry to Santiago. The Americans and Cubans forcibly began a siege of the city. During the nights, Cuban troops dug successive series of "trenches" (raised parapets), toward the Spanish positions. Once completed, these parapets were occupied by U.S. soldiers and a new set of excavations went forward. The Spanish forces surrendered on 17 July. In the Treaty of Paris (1898), Spain renounced its sovereignty over Cuba without naming a receiving country. Cuba then established its own civil government, which was recognized by the United States as the legal government of Cuba upon the announcement of the termination of United States Military Government (USMG) jurisdiction over the island on May 20, 1902. This date is celebrated as Independence day for the Republic of Cuba.

20th century

World War II

Cuba entered World War II in December 1941. The Cuban Navy performed convoy escort duties and antisubmarine patrols during the Battle of the Caribbean; despite its small size, the Cuban Navy quickly developed a reputation for being extremely efficient. The most notable success of Cuban forces was the sinking of German submarine U-176 by a Cuban submarine chaser squadron. Six Cuban merchant vessels were sunk by German submarines in the conflict and 79 Cuban sailors were killed.

1952 coup

Military strongman Fulgencio Batista staged a coup on 10 March 1952, removing Carlos Prío Socarrás from power. Cubans in general were stunned, but they were reluctant to fight. Batista created a consultative council from pliable political personalities of all parties who appointed him President months before elections were to be held in 1952. Batista’s past democratic and pro-labor tendencies and the fear of another episode of bloody violence gained him tenuous support from the bankers, and the leader of the major labor confederation.

The Cuban Revolution

The Cuban Revolution started as an uprising that resulted in the overthrow of the Fulgencio Batista government on 1 January 1959 by Fidel Castro and other revolutionary elements in the country. The Revolution began on 26 July 1953, when a group of armed guerrillas attacked the Moncada Barracks. From 1956 through the middle of 1958, Castro and his forces staged successful attacks on Batista garrisons in the Sierra Maestra mountains. Che Guevara and Raúl Castro helped to consolidate rebel political control in the mountains through guerrilla fighting, building trust with campesinos, and severely punishing traitors and informers. The irregular and poorly armed rebels harassed the Batista forces in the forests and mountains of Oriente Province.

Batista's troops were defeated by Castro's fighters at the Battle of La Plata (11–21 July 1958). Although Batista's army gained a victory at the Battle of Las Mercedes (29 July–8 August 1958), the army commander Eulogio Cantillo allowed the rebels to escape back into the Sierra Maestra mountains. As the rebels emerged from the Sierra Maestra into more populated areas, they seized significant amounts of Dominican-made Cristóbal Carbines and hand grenades; these became the rebels' standard weapons. The final blow to Batista's government came during the Battle of Yaguajay (19–30 December 1958). After suffering a crucial defeat at the Battle of Santa Clara, Batista fled the country and Castro came into power.

Dominican Republic invasion attempt

Cuban military intervention abroad began on 14 June 1959 with an attempted invasion of the Dominican Republic by a mixed group of Cuban soldiers and Cuban-trained Dominican irregulars.[31] The expeditionary force was massacred just hours after having disembarked.[32]

Castro feared a possible attack from the Dominican Republic and was determined to acquire jet aircraft as a preventive measure: Cuba's ability to repel an air attack was very precarious, since the Dominicans possessed 40 jet aircraft whereas Cuba had only one.[33] The Dominican Air Force had the theoretical ability to reach and bomb Havana within 3 hours.[34]

Escambray rebellion

Militant anti-Castro groups, funded by exiles, by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and by Rafael Trujillo's Dominican government, carried out armed attacks and set up guerrilla bases in the Escambray Mountains. This led to a failed rebellion, which lasted longer and involved more soldiers than the Cuban Revolution. Near 1,000 families were forcibly uprooted from the Escambray countryside, leaving the rebels without their habitat to support them; the uprooted men were sent to prisons or executed after trial.

Bay of Pigs Invasion

The Bay of Pigs Invasion (known as La Batalla de Girón in Cuba), was an unsuccessful attempt by a U.S.-trained force of Cuban exiles to invade southern Cuba with support from U.S. armed forces to overthrow the Cuban government of Fidel Castro. The plan was launched in April 1961, less than three months after John F. Kennedy assumed the presidency in the United States. The Cuban armed forces, trained and equipped by Eastern Bloc nations, defeated the exile combatants in three days. Bad Cuban-American relations were exacerbated the following year by the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis (October Crisis in Cuba) was a confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union over nuclear missiles that were deployed in Cuba and Turkey. The Russian missiles were placed both to protect Cuba from further attacks by the United States after the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion, and in response to the U.S. deploying Thor missiles with nuclear warheads on the Soviet border in Turkey.

The situation reached the crisis point when U.S. reconnaissance imagery revealed Soviet nuclear missile installations on the island, and ended fourteen days later when the Americans and Soviets each agreed to dismantle their installations, and the Americans agreed not to invade Cuba.

Congo Crisis

The Congo Crisis was a period of turmoil in the Congo that began with national independence from Belgium and ended with the seizing of power by Joseph Mobutu. During the Congo Crisis, a Cuban expedition led by Che Guevara trained the Simba rebels to fight against the weak central government of Joseph Kasa-Vubu and the forces of Mobutu Sese Seko. This would be Cuba's first military action in Africa. The rebellion failed, leading the Cuban mission to withdraw.

Sand War

In 1963, Cuba assisted Algeria in the Sand War against Morocco.[35] Cuba sent 300–400 tank troops and some 40 Russian-built T-34 tanks, which engaged in combat.[36]

Guinea-Bissau War of Independence

Some 40–50 Cubans fought against Portugal in Guinea-Bissau each year from 1966 until independence in 1974; several Cubans were killed in the field by Portuguese troops.[31]

Bolivian campaign

During the 1960s, the National Liberation Army began a Communist insurgency in Bolivia. The National Liberation Army was established and funded by Cuba and led by Che Guevara.

The National Liberation Army was defeated and Che Guevara was captured by the Bolivia government aided by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency. Bolivian Special Forces were informed of the location of Guevara's guerrilla encampment. On 8 October 1967, the encampment was encircled, and Guevara was captured and later executed by Bolivian forces.

Eritrean War

Cubans trained Eritreans but later, in a political reversal, trained Ethiopian Marxist forces who were fighting against Eritreans.

War of Attrition

Cuba deployed 2,000 troops to support the Syrian forces fighting against Israel during the War of Attrition (November 1973–May 1974) that followed the Yom Kippur War (October 1973).[37] Cuban tank units engaged in artillery duels with the Israelis in the Golan Heights. Precise Cuban casualty numbers are unknown.[38]

Cuban intervention in Angola

Between 1975 and 1991, the Cuban military provided support for the left wing MPLA movement in a series of civil wars. During these conflicts the MPLA emerged victorious due in part to the substantial aid received from Cuba.

The Angolan War of Independence was a struggle for control of Angola between guerilla movements and Portuguese colonial authority. Cuba supplied the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) rebels with weapons and soldiers to fight. The Cuban military would fight alongside the MPLA in major battles.

The Angolan Civil War was a 27-year civil war that devastated Angola following the end of Portuguese colonial rule in 1974. The conflict was fought by the MPLA against UNITA and the National Liberation Front of Angola (FNLA). MPLA was aided by Cuba and the Soviet Union, and UNITA and FNLA were supported by South Africa, United States and Zaire. It became Africa's longest running conflict. Cuban forces were instrumental in the defeat of South African and Zairian troops.[39] Cuban forces also defeated the FNLA and UNITA armies in conventional warfare and established MPLA control over most of Angola.[40]

In 1987–88, South Africa again sent military forces to Angola, and several inconclusive battles were fought between Cuban and apartheid forces. Cuba, Angola and South Africa signed the Tripartite Accord on 22 December 1988, in which Cuba agreed to withdraw troops from Angola in exchange for South Africa withdrawing soldiers from Angola and South West Africa. Cuba suffered up to 18,000 casualties (2,000-3,000 dead and 15,000 wounded) during the Angolan intervention.[41] Regular South African forces may have suffered only 1,000 dead, excluding losses among paramilitary units and other irregular formations.[42]

Angola paid a huge cost for the conflict: 800,000 dead,[43] 4 million displaced, a rural infrastructure and economy virtually destroyed, the majority of the population impoverished, almost two million facing a famine, and human rights abuses becoming the norm. Hundreds of thousands of anti-personnel mines were laid across the country and are still in place, causing thousands of deaths and mutilating 70,000 people.

Ogaden War

The Ogaden War was a conflict between Somalia and Ethiopia between 1977 and 1978. Fighting erupted in the Ogaden region as Somalia attempted to annex it. When the Soviet Union began to support the Ethiopian Derg government instead of the Somali government, other Communist nations followed. In late 1977, the Cuban military deployed 16,000 combat troops along with aircraft to support the Derg government and the USSR military advisors in the region.

By March 1978, following months of tank warfare, a combined force of Ethiopian and Cuban troops (led by Russian and Cuban officers) repulsed the enemy. The Somali army, which had taken a severe beating from Cuban artillery and air attacks,[44] was destroyed as a fighting force.[45] Cuban losses were 160 killed,[46] 11 tanks and 3 planes.

Invasion of Grenada

A 748-person count of Cuban workers (all but 43 of whom were construction workers) was present in Grenada at the time of the invasion of Grenada by the U.S. in 1983. Cuba was involved in the construction of a civil airport in Saint John, Grenada. Cuban losses during the conflict were 24 killed (only 2 of whom were professional soldiers), 59 wounded, and 606 made prisoners (later repatriated to Cuba). In 2008, the Government of Grenada announced the construction of a monument to honor the Cubans killed during the invasion by Genelle Figuroa. At the time of the announcement the Cuban and Grenadian government are still seeking to locate a suitable site for the monument.

Salvadoran Civil War

The Salvadoran Civil War was fought by the El Salvador government waging a vicious crackdown against various left-wing rebels, as well as committing war crimes against civilians, one example of which being the El Mozote massacre. Cuba supplied the rebels with weapons and advisors.

Nicaraguan Civil War

During the Sandinista revolution and the following Civil War, Cuba gave aid and support to the Sandinista government of Daniel Ortega. The Sandinista government was fighting the American backed rebels (aka) Contras. The conflict ended with the 1990 presidential election where Ortega lost to Violeta Barrios de Chamorro.

See also

References

- ↑ Suchlicki, Jaime (1989). The Cuban Military Under Castro. Transaction Publishers. p. 41.

- ↑ Eckstein, Susan (1994). Back from the Future: Cuba Under Castro. Princeton University Press. p. 187.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Klein 1966, p. 17.

- ↑ Andrews, Kenneth R. (2017). English Privateering Voyages to the West Indies, 1588-1595. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781317142959.

- ↑ Marley, David (2008). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the Western Hemisphere. ABC-CLIO. p. 137. ISBN 9781598841015.

- 1 2 Bremden, D. Van. "The Capture of the Spanish Silver Fleet Near Havana, 1628". snr.org.uk. Royal Museums, Grenwich.

- 1 2 Grant, R. G. (2011). Battle at Sea: 3,000 Years of Naval Warfare. DK Publishing. p. 127. ISBN 9780756657017.

- 1 2 3 Klein 1966, p. 20.

- ↑ Klein 1966, p. 19.

- ↑ Ogelsby 1969, p. 475.

- ↑ Ogelsby 1969, p. 479.

- 1 2 3 Ogelsby 1969, p. 480.

- ↑ Ogelsby 1969, p. 481.

- ↑ Ogelsby 1969, p. 488.

- ↑ Ogelsby 1969, p. 484.

- ↑ Ogelsby 1969, p. 486.

- ↑ Ogelsby 1969, p. 487.

- 1 2 3 Phifer, Mike (2022). "Daring Strike on Havana". warfarehistorynetwork.com. Sovereign Media. Retrieved 11 December 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Ferrer, Ada (2021). Cuba: An American History. Scribner. ISBN 9781501154577.

- ↑ "General Bernardo Galvez in the American Revolution".

- 1 2 Klein 1966, p. 22.

- ↑ Klein 1966, p. 23.

- ↑ Klein 1966, p. 24.

- ↑ Conway, Christopher (2015). Nineteenth-Century Spanish America: A Cultural History. Vanderbilt University Press. p. 187. ISBN 9780826520616.

- ↑ Klein 1966, p. 25.

- 1 2 3 4 Scheina, Robert L. (2003). Latin America's Wars: Volume 1. Potomac Books.

- ↑ Foner, Philip S. (1989). Antonio Maceo: The "Bronze Titan" of Cuba's Struggle for Independence. NYU Press. p. 21.

- ↑ Editions, Dupont Circle; Chao, Raúl Eduardo (2009). Baraguá: Insurgents and Exiles in Cuba and New York During the Ten Year War on Independence (1868-1878). p. 293.

- ↑ Cecil, Leslie (2012). New Frontiers in Latin American Borderlands. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 37.

- ↑ "Victimario Histórico Militar".

- 1 2 "Foreign Intervention by Cuba" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 22, 2017.

- ↑ Castañeda, Jorge G. (2009). Companero: The Life and Death of Che Guevara. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 147.

- ↑ Cuban Studies 33. University of Pittsburgh Pre. 2003. p. 77.

- ↑ "The Most Powerful Air Force In The Caribbean".

- ↑ "Cuba and Algerian revolutions: an intertwined history".

- ↑ To Make a World Safe for Revolution: Cuba's Foreign Policy. Harvard University Press. 2009. p. 175.

- ↑ Karsh, Efraim. Soviet Policy towards Syria since 1970. p. 45.

- ↑ Perez, Cuba, Between Reform and Revolution, p. 377-379

- ↑ Holloway, Thomas H. (2011). A Companion to Latin American History. John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ Africa, Problems & Prospects: A Bibliographic Survey. U.S. Department of the Army. 1977. p. 221.

- ↑ Bawden, John R. (2019). Latin American Soldiers: Armed Forces in the Region's History. Routledge.

- ↑ Tillema, Herbert K. (2019). International Armed Conflict Since 1945: A Bibliographic Handbook Of Wars And Military Interventions. Routledge.

- ↑ "Angola (1975 - 2002)" (PDF).

- ↑ Kirk, J.; Erisman, H. Michael (2009). Cuban Medical Internationalism: Origins, Evolution, and Goals. Springer. p. 75.

- ↑ Clodfelter, Micheal (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015, 4th ed. McFarland. p. 566. ISBN 978-0786474707.

- ↑ "La Fuerza Aérea de Cuba en la Guerra de Etiopía (Ogadén)".

Further reading

- Klein, Herbert S. (1966). "The Colored Militia of Cuba: 1568–1868" (PDF). Caribbean Studies. 6 (1): 17–27.

- Ogelsby, J. C. M. (1969). "Spain's Havana Squadron and the Preservation of the Balance of Power in the Caribbean, 1740-1748". Hispanic American Historical Review. 49 (3): 473–488. doi:10.1215/00182168-49.3.473.