The Crimea Germans (German: Krimdeutsche) were ethnic German settlers who were invited to settle in the Crimea as part of the East Colonization.

History

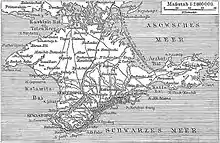

From 1783 onwards, there was a systematic settlement of Russians, Ukrainians, and Germans to the Crimean Peninsula (in what was then the Crimean Khanate) in order to weaken the Crimean Tatar population.

The first planned settlements of Germans in Crimea were founded over 1805–1810 with the support of Czar Alexander I. The first settlements were:

- Friedental – in the district of Simferopol; formed in 1806 by Lutherans

- Heilbrunn – in the district of Feodosiya; formed in 1809 by Lutherans

- Kronental – in the district of Simferopol; formed in 1810 by Lutherans and Catholics

- Neusatz – in the district of Simferopol; formed in 1806 by Lutherans

- Rosental – in the district of Simferopol; formed in 1806 by Catholics

- Staryj Krim (old Crimea) – in the district Feodosiya; formed in 1805 by Lutherans and Catholics

- Sudak – in the district of Feodosiya; formed in 1805 by Lutherans

- Zuerichtal – in the district of Feodosiya; formed in 1805 by Swiss and Lutherans

All of these early colonies were located in the Yayla-mountains of Crimea and were mostly Swabian wine-farmers. However over time only Sudak produced quality wine and the other settlements soon turned to agriculture. The second generation didn't have enough land and soon young men started buying land from the Russian aristocracy and creating new ("daughter") colonies.

Later Mennonites began to move from Ukraine into Crimea.

Details are vague but during the 19th century a "German hospital" and dispensary arose in the Simferopol suburb of Nowyj gorod (called Neustadt or new city—now this is Kyivskyi District of Simferopol).[1]

Soviet Persecution

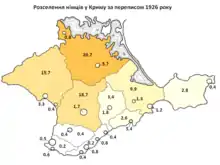

On 18 October 1921, the so-called Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was created as part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (i.e. part of Russia). In place of today Krasnohvardiiske Raion there were created two national districts for Germans Biyuk-Onlar and Telman. Under the Soviet regime many Volksdeutsche were persecuted by gangs of Russian peasants as landowning Kulaks or class enemy bourgeoisie. In 1939, two years before their deportation to Central Asia, around 60,000 of the 1.1 million inhabitants of Crimea were German and "they had their own administrative raion in the Crimean Republic.".[2]

Exiles dispersed all over the world. In Canada, Reynold Rapp, a farmer and Lutheran immigrant from the Crimea, became a Progressive Conservative Member of Parliament. A strong supporter of the British heritage of freedom in his adoptive country, Rapp opposed the replacement of the Canadian Red Ensign with a new Maple leaf flag in 1964. He told reporters: "I may be the only man in this House who has lived under the Hammer & Sickle. A flag is not just a bunting: it represents so much more than that."[3]

Nazi invasion, deportation and exile

In late 1941, following the Axis invasion of the western regions of the USSR, Soviet authorities forcibly removed almost 53,000 native Germans of Crimea eastwards to Siberia and Central Asia on entirely spurious allegations that they were spies for the Third Reich. Consequently, many died in transit, although later they could not be seriously blamed for Nazi crimes in the region.

"Stalin had no doubts about the loyalty of the ethnic German minority. He considered them all potential traitors, and in line with his inherent "Great Russian" chauvinism, had already decided to deport the entire community to internal exile in case of war. Therefore, when Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, a decision was made by Stalin to evacuate all ethnic Germans from the Western Regions of the Soviet Union. The first evacuations, which, in reality, were expulsions, as the inhabitants were never allowed to return to their homes, were decreed by the Supreme Soviet already on June 22. Action to deport every ethnic German from the Crimea began on August 15. Although the decree stated that old people would not have to leave, everyone was expelled—first to Stavropol, and then Rostov in Southern Ukraine, near Crimea; but then all were sent on to forced labor camps and special settlements in Kazakhstan, Central Asia. The deportees were not told where they were going, how long they would stay there and how much food to take; they were given only three or four hours to pack. The result was starvation for many and, due to the confusion, the separation of a large number of families. In all, as many as 60,000 ethnic Germans were expelled from the Crimea at this time."[4]

It is unclear whether any Crimea Germans remained at all during the Nazi occupation—German policy involved evacuating all surviving Soviet Volksdeutsche to settlements in Poland.[5] The Nazi Generalkommissar for Crimea, the Austrian Alfred Frauenfeld, toyed with the idea of resettling ethnic Germans (Volksdeutsche) here from Italian South Tyrol after the war, and several cities of the envisaged Gotengau were renamed with spurious German names (Simferopol became Gotenburg and Sevastopol became Theodorichhafen for example).[6]

Perestroika and post-Soviet times

Crimean Germans were only allowed to return to the peninsula after Perestroika. The German reunification brought a rebirth of Crimean-German culture and, in 1994, they had a small representation in the Crimean Parliament.

The 1991 RSFSR law On the Rehabilitation of Repressed Peoples addressed rehabilitation of all ethnicities repressed in the Soviet Union. However the law had various deficiencies, including unclear legal status of a number of peoples, such as Crimean Tatars and Crimean Germans moved across the borders of Soviet republics, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.[7] After the annexation of Crimea by Russia, on April 21, 2014 Vladimir Putin signed the decree No 268 "О мерах по реабилитации армянского, болгарского, греческого, крымско-татарского и немецкого народов и государственной поддержке их возрождения и развития". ("On the Measures for the Rehabilitation of Armenian, Bulgarian, Greek, Crimean Tatar and German Peoples and the State Support of Their Revival and Development"),[8] amended by Decree no. 458 of September 12, 2015.[9] The decree addressed the status of the mentioned peoples which resided in Crimean ASSR and were deported from there.

See also

References

- ↑ "Die deutschen Kolonien in der Krim". Heimutbuch der Landsmannschaft der Deutschen aus Russland (in German). 1960.

- ↑ Lumans, Valdis O. (1993). Himmler's Auxiliaries: the Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle and the German minorities of Europe, 1939–1945. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 128. ISBN 0-8078-2066-0.

- ↑ The Globe and Mail, October 3, 1964

- ↑ Merten, Ulrich (2015). Voices from the Gulag; the Oppression of the German Minority in the Soviet Union. Lincoln, Nebraska: American Historical Society of Germans from Russia. pp. 158–159. ISBN 978-0-692-60337-6.

- ↑ Lumans, Valdis O. (1993). Himmler's Auxiliaries: the Volksdeutsche Mittelstelle and the German minorities of Europe, 1939–1945. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 250. ISBN 0-8078-2066-0.

- ↑ Toynbee, Arnold; Toynbee, Veronica, eds. (1954). "Ukraine, under German Occupation, 1941–44". Hitler's Europe. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 316–337. OCLC 4355796.

- ↑ Правовые вопросы реабилитации репрессированных народов, in Pravo i Zhizn, 1994, no 4, p. 26.

- ↑ Внесены изменения в указ о мерах по реабилитации армянского, болгарского, греческого, крымско-татарского и немецкого народов и государственной поддержке их возрождения и развития

- ↑ Указ Президента Российской Федерации от 12.09.2015 г. № 458

Further reading

- Conquest, Robert (1970). The Nation Killers: The Soviet Deportation of Nationalities. London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-10575-3.