| Cricoid cartilage | |

|---|---|

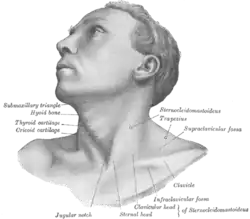

Anterolateral view of head and neck (cricoid cartilage labeled at center left) | |

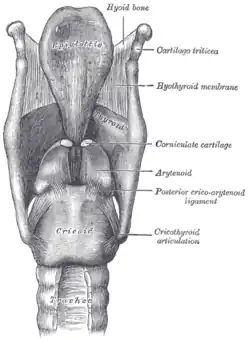

Antero-lateral view of the ligaments of the larynx (cricoid cartilage visible near bottom center) | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | 4th and 6th branchial arch |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Cartilago cricoidea |

| MeSH | D003413 |

| TA98 | A06.2.03.001 |

| TA2 | 978 |

| FMA | 9615 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The cricoid cartilage /ˌkraɪkɔɪd ˈkɑːrtɪlɪdʒ/, or simply cricoid (from the Greek krikoeides meaning "ring-shaped") or cricoid ring, is the only complete ring of cartilage around the trachea. It forms the back part of the voice box and functions as an attachment site for muscles, cartilages, and ligaments involved in opening and closing the airway and in producing speech.

Anatomy

The cricoid cartilage is the only laryngeal cartilage to form a complete circle around the airway. It is smaller yet thicker and tougher than the thyroid cartilage above.[1]

It articulates superiorly with the thyroid cartilage, and the paired arytenoid cartilage. Inferiorly, the trachea attaches onto it.[1] It occurs at the level of the C6 vertebra.

Structure

The posterior part of the cricoid cartilage (cricoid lamina) is somewhat broader than the anterior and lateral part (cricoid arch). Its shape is said to resemble a signet ring.[2]

Cricoid arch

The cricoid arch is the curved and vertically narrow anterior portion of the cricoid cartilage. Anteriorly, it measures 5-7 mm superoinferiorly; it becomes wider on eithers side towards its transition into the cricoid lamina of that side.[1]

The superior margin of the cricoid arch is rather elliptical in outline; the inferior margin is nearly horizontal and circular in outline.[1]

The cricoid arch is palpable inferior to the laryngeal prominence, with an interval containing a depression (beneath which is the conus elasticus) between the two.[1]

Cricoid lamina

The cricoid lamina is the roughly quadrilateral broader and flatter posterior portion of the cricoid cartilage. It measures 2-3 cm superoposteriorly.[1]

The cricoid lamina exhibits a midline vertical ridge posteriorly; the ridge creates posterior concavities to either side.[1]

Relations

It is anatomically related to the thyroid gland; although the thyroid isthmus is inferior to it, the two lobes of the thyroid extend superiorly on each side of the cricoid as far as the thyroid cartilage above.

Attachments

The thyroid cartilage and cricoid cartilage are connected medially by the median cricothyroid ligament, and postero-laterally by the cricothyroid joints.

The cricoid is joined with the first tracheal ring inferiorly by the cricotracheal ligament.

The cricothyroid muscle attaches to the anterior and lateral external aspects of the cricoid arch.[1]

The cricopharyngeus part of inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle attaches onto the cricoid arch posterior to the attachment of the cricothyroid muscle.[1]

Histology

It is made of hyaline cartilage, and so can become calcified or even ossified, particularly in old age.

Function

The function of the cricoid cartilage is to provide attachments for the cricothyroid muscle, posterior cricoarytenoid muscle and lateral cricoarytenoid muscle muscles, cartilages, and ligaments involved in opening and closing the airway and in speech production.

Clinical significance

When intubating a patient under general anesthesia prior to surgery, the anesthesiologist will press on the cricoid cartilage to compress the esophagus behind it so as to prevent gastric reflux from occurring: this is known as the Sellick manoeuvre. The Sellick Manoeuvre is typically only applied during a Rapid Sequence Induction (RSI), an induction technique reserved for those at high risk of aspiration.

The Sellick maneuver was considered the standard of care during rapid sequence induction for many years.[3] The American Heart Association still advocates the use of cricoid pressure during resuscitation using a BVM, and during emergent oral endotracheal intubation.[4] However, recent research increasingly suggests that cricoid pressure may not be as advantageous as once thought. The initial article by Sellick was based on a small sample size at a time when high tidal volumes, head-down positioning, and barbiturate anesthesia were the rule.[5]

Cricoid pressure may frequently be applied incorrectly.[6][7][8][9][10] Cricoid pressure may frequently displace the esophagus laterally, instead of compressing it as described by Sellick.[11][12] Several studies demonstrate some degree of glottic compression[13][14][15] reduction in tidal volume and increase in peak pressures.[16] Based on the current literature, the widespread recommendation that cricoid pressure be applied during every rapid sequence intubation is quickly falling out of favor.

Gastric reflux could cause aspiration if this is not done considering the general anesthesia can cause relaxation of the gastroesophageal sphincter allowing stomach contents to ascend through the esophagus into the trachea.

A medical procedure known as a cricoidectomy can be performed in which part or all of the cricoid cartilage is removed. This is commonly done to relieve blockages within the trachea.[17]

Fractures of the cricoid cartilage can be seen after manual strangulation also known as throttling.

Additional images

Cricoid cartilage.

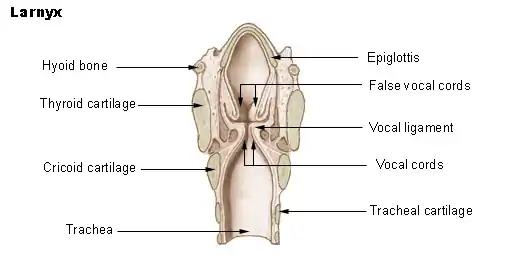

Cricoid cartilage. Larynx

Larynx The cartilages of the larynx. Posterior view.

The cartilages of the larynx. Posterior view. Ligaments of the larynx. Posterior view.

Ligaments of the larynx. Posterior view. Sagittal section of the larynx and upper part of the trachea.

Sagittal section of the larynx and upper part of the trachea. Cricoid cartilage

Cricoid cartilage

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Standring, Susan (2020). Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (42th ed.). New York. p. 719. ISBN 978-0-7020-7707-4. OCLC 1201341621.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Vashishta, Rishi (7 December 2017). "Larynx Anatomy". Medscape. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ↑ Salem MR, Sellick BA, Elam JO. The historical background of cricoid pressure in anesthesia and resuscitation. Anesth Analg 1974;53(2):230-232.

- ↑ American Heart Association (2006). Textbook of Advanced Cardiac Life Support. Dallas, TX: American Heart Association.

- ↑ Maltby, J. M., & Berialt, M. T. (2002). Science, pseudoscience and Sellick. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia, 49(5), 443-447

- ↑ Escott MEA, Owen H, Strahan AD, Plummer JL. Cricoid pressure training: how useful are descriptions of force? Anaesth Intensive Care 2003;31:388-391

- ↑ Owen H, Follows V, Reynolds KJ, Burgess G, Plummer J. Learning to apply effective cricoid pressure using a part task trainer. Anaesthesia 2002;57(11):1098-1101

- ↑ Walton S, Pearce A. Auditing the application of cricoid pressure. Anaesthesia 2000;55:1028-1029

- ↑ Koziol CA, Cuddleford JD, Moos DD. Assessing the force generated with the application of cricoid pressure. AORN J 2000;72:1018-1030

- ↑ Meek T, Gittins N, Duggan JE. Cricoid pressure: knowledge and performance amongst anaesthetic assistants. Anaesthesia 1999;54(1):59-62.

- ↑ Smith, K. J., Dobranowski, J., Yip, G., Dauphin, A., & Choi, P. T. (2003). Cricoid pressure displaces the esophagus: an observational study using magnetic resonance imaging. Anesthesiology, 99(1), 60-64;

- ↑ Smith, K. J., Ladak, S., Choi, Pt L., & Dobranowski, J. (2002). The cricoid cartilage and the oesophagus are not aligned in close to half of adult patients. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia, 49(5), 503-507.

- ↑ Palmer, JHM, Ball, D.R. The effect of cricoids pressure on the cricoids cartilage and vocal cords: An endoscopic study in anaesthetized patients. Anaesthesia (2000): 55; 260-287

- ↑ Hartsilver, E. L., Vanner, R. G. Airway obstruction with cricoids pressure. Anesthesia (2000): 55: 208-211

- ↑ Haslam, N., Parker, L., and Duggan, J.E. Effect of cricoid pressure on the view at laryngoscopy. Anesthesia (2005): 60: 41-47

- ↑ Hocking, G., Roberts, F.L., Thew, M.E. Airway obstruction with cricoids pressure and lateral tilt. Anesthesia (2001), 56; 825-828

- ↑ Michihiko Sonea1; Tsutomu Nakashimaa1; Noriyuki Yanagita (1995) "Laryngotracheal separation under local anaesthesia for intractable salivary aspiration: cricoidectomy with fibrin glue support" The Journal of Laryngology & Otology:Cambridge University Press

External links

- Illustration at nda.ox.ac.uk

- Anatomy figure: 32:04-06 at Human Anatomy Online, SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Skeleton of the larynx."

- lesson11 at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (larynxsagsect)