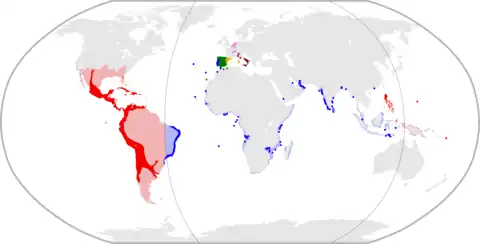

The Council of the Indies (Spanish: Consejo de las Indias), officially the Royal and Supreme Council of the Indies (Spanish: Real y Supremo Consejo de las Indias, pronounced [reˈal i suˈpɾemo konˈsexo ðe las ˈindjas]), was the most important administrative organ of the Spanish Empire for the Americas and those territories it governed, such as the Spanish East Indies. The crown held absolute power over the Indies and the Council of the Indies was the administrative and advisory body for those overseas realms. It was established in 1524 by Charles V to administer "the Indies", Spain's name for its territories. Such an administrative entity, on the conciliar model of the Council of Castile, was created following the Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire in 1521, which demonstrated the importance of the Americas. Originally an itinerary council that followed Charles V, it was subsequently established as an autonomous body with legislative, executive and judicial functions by Philip II of Spain and placed in Madrid in 1561.[2]

.jpg.webp)

The Council of the Indies was abolished in 1812 by the Cortes of Cádiz, briefly restored in 1814 by Ferdinand VII of Spain, and definitively abolished in 1834 by the regency, acting on behalf of the four-year-old Isabella II of Spain.[3][4]

History

Queen Isabella had granted extensive authority to Christopher Columbus, but then withdrew that authority, and established direct royal control, putting matters of the Indies in the hands of her chaplain, Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca in 1493. The Catholic Monarchs (Isabella and Ferdinand) designated Rodríguez de Fonseca to study the problems related to the colonization process arising from what was seen as tyrannical behavior of Governor Christopher Columbus and his misgovernment of Natives and Iberian settlers. Rodríguez de Fonseca effectively became minister for the Indies and laid the foundations for the creation of a colonial bureaucracy. He presided over a committee or council, which contained a number of members of the Council of Castile (Consejo de Castilla), and formed a Junta de Indias of about eight counselors. Emperor Charles V was already using the term "Council of the Indies" in 1519.

The Council of the Indies was formally created on August 1, 1524.[5] The king was informed weekly, and sometimes daily, of decisions reached by the Council, which came to exercise supreme authority over the Indies at the local level and over the Casa de Contratación ("House of Trade") founded in 1503 at Seville as a customs storehouse for the Indies. Civil suits of sufficient importance could be appealed from an audiencia in the New World to the Council, functioning as a court of last resort.[6] There were two secretaries of the Council, one in charge of the Viceroyalty of New Spain, encompassing Mexico, Nueva Galicia, Guatemala, Hispaniola, and their dependencies in the Spanish East Indies; the other in charge of Peru, Chile, Tierrafirme (northern South America), and the Kingdom of New Granada. The name of the Council did not change with the addition of the indias orientales of the East Indies and other Pacific territories claimed by Spain to the original indias occidentales.[7]

Internecine fighting and political instability in Peru and the untiring efforts of Bartolomé de las Casas on behalf of the natives' rights resulted in Charles's overhaul of the structure of the Council in 1542 with issuing of the "New Laws", which put limits on the rights of Spanish holders of encomiendas, grants of indigenous labor. Under Charles II the Council undertook the project to formally codify the large volume of Council and Crown's decisions and legislation for the Indies in the 1680 publication, the Laws of the Indies (es:Recopilación de las Leyes de Indias) and re-codified in 1791.[8]

The Council of the Indies was usually headed by an ecclesiastic, but the councilors were generally non-clerics trained in law. In later years, nobles and royal favorites were in the ranks of councilors, as well as men who had experience in the high courts (Audiencias) of the Indies. A key example of such an experienced councilor was Juan de Solórzano Pereira, author of Política Indiana, who served in Peru prior to being named to the Council of the Indies[9] and led the project on the Laws of the Indies. Other noteworthy Presidents of the Council were es:Francisco Tello de Sandoval; es:Juan de Ovando y Godoy; Pedro Moya de Contreras, former archbishop of Mexico; and Luis de Velasco, marqués de Salinas, former viceroy of both Mexico and Peru.

Although initially the Council had responsibility for all aspects of the Indies, under Philip II the financial aspects of the empire were shifted to the Council on Finance in 1556-57, a source of conflict between the two councils, especially since Spanish America came to be the source of the empire's wealth. When the Holy Office of the Inquisition was established as an institution in Mexico and Lima in the 1570s, the Council of the Indies was removed from control. The head of the Supreme Council of the Inquisition, es:Juan de Ovando y Godoy became president of the Council of the Indies 1571-75. He was appalled by the ignorance of the Indies by those serving on the Council. He sought the creation of a general description of the territories, which was never completed, but the Relaciones geográficas were the result of that project.[10]

The height of the Council's power was in the sixteenth century. Its power declined and the quality of the councillors decreased. In the final years of the Habsburg dynasty, some appointments were sold or were accorded to people obviously unqualified, such as a nine-year-old boy, whose father had rendered services to the crown.[11]

With the ascension of the Bourbon dynasty at the start of the eighteenth century, a series of administrative changes, known as the Bourbon reforms, were introduced. In 1714 Philip V created a Secretariat of the Navy and the Indies (Secretaría de Marina e Indias) with a single Minister of the Indies, which superseded the administrative functions of the Council, although the Council continued to function in a secondary role until the nineteenth century. Fifty years later Charles III set up a separate Secretary of State for the Indies (Secretarío del Estado del Despacho Universal de Indias).[12] In the late eighteenth century, the Council became powerful and prestigious again, with a great number of well qualified councillors with experience in the Indies.[13] In 1808 Napoleon invaded Spain placed his brother, Joseph Napoleon on the throne. The Cortes of Cádiz, the body Spaniards considered the legitimate government in Spain and its overseas territories in the absence of their Bourbon monarch, abolished the Council in 1812. It was restored in 1814 upon Ferdinand VII's restoration, and the autocratic monarch appointed a great number of Councillors with American experience.[14] The Council was finally abolished in 1834, a year after Ferdinand VII's death and after most of Spain's empire in the Americas declared independence.

The archives of the Council, the Archivo General de Indias one of the major centers of documentation for Spanish, Spanish American, and European history, are housed in Seville.

See also

References

- ↑ "LAS INDIAS - Spanish Indies". Hubert Herald.

- ↑ Scott, Hamish M. (2015). The Oxford Handbook of Early Modern European History, 1350-1750: Cultures and power. ISBN 978-0-19-959726-0.

- ↑ Fernando Cervantes, "Council of the Indies" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, vol. 1, p. 36163. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997.

- ↑ El Consejo Real de Castilla y la Ley

- ↑ Gibson, Charles (1966). Spain in America. New York: Harper & Row. pp. 92.

- ↑ Gibson, 94-95.

- ↑ Recopilación de las leyes de Indias, Libro II, Título VI.

- ↑ Gibson, 109-110, note 24.

- ↑ Cervantes, "Council of the Indies" p. 361.

- ↑ Cervantes, "Council of the Indies", p. 362.

- ↑ Burkholder, Mark A. "Council of the Indies", vol. 2, p. 293. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- ↑ Gibson, 167-168.

- ↑ Burkholder, "Council of the Indies" p. 293.

- ↑ Burkholder, "Council of the Indies" p. 293.

Further reading

- Burkholder, Mark A. Biographical Dictionary of Councilors of the Indies, 1717-1808. Westport: Greenwood Press, 1986. ISBN 0-313-24024-8

- Burkholder, Mark A. "Council of the Indies" in Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture, vol. 2, p. 293. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons 1996.

- Cervantes, Fernando. "Council of the Indies" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, vol. 1, pp. 361–3. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997.

- Haring, Clarence H. The Spanish Empire in America. New York: Oxford University Press 1947.

- Merriman, R.G. The Rise of the Spanish Empire in the Old World and the New, 4 vols. New York: Cooper Square 1962.

- Parry, J.H. The Spanish Theory of Empire in the Sixteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1940.

- Schäfer, Ernesto. El consejo real y supremo de las Indias. vol 1. Seville: M. Carmona 1935.

- Solórzano y Pereira, Juan de. Política Indiana. 2 vols. Mexico City: Secretaria de Programación y Presupuesto 1979.

- Zavala, Silvio. Las instituciones jurídicas en la conquista de América. 3rd. ed. Mexico City: Porrúa 1935.

.svg.png.webp)