The favourable conservation status of wolves is the definition of a wolf population that is no longer threatened with extinction, that is capable of long-term survival. In Europe the favourable conservation status is defined by the Guidelines for Population Level Management Plans for Large Carnivores. It is the minimum viable population, that can be of different numbers of wolves depending on their connectivity with neighbouring populations. According to the IUCN guidelines, at least 1000 adult animals are required for isolated populations. If a wolf population is effectively linked genetically and demographically with other wolf populations, more than 250 mature wolves may be sufficient.[1]

Developments

Before the entry into force of the Bern Convention of 1979 in 1982,[2] wolves had been decimated to isolated relict populations in some of their formerly extensive distribution areas to end the damage caused by predation to livestock. Populations in Europe have recovered during the four decades of strict protection and are largely in a favourable conservation status. The innate instinctive behaviour of the wolf, with its enormous potential for long-distance migration, favours both its rapid expansion and the genetic connectivity of the various populations.[3] Using satellite telemetry, it has been measured that some wolves travel over 1000 kilometres within a few months. They can colonise new areas relatively quickly.[4][5] Population genetic analyses by Maris Hindrikson et al. showed a range of 650 to 850 km when using spatial autocorrelation based on three characteristics of genetic diversity. This suggests that the genetic diversity of a wolf population can be influenced by populations up to 850 km away.[6]

Population genetics criteria

Both the number of individuals and the gene flow between populations are important for the conservation status for which a viable population must be available. Luigi Boitani means a minimum number of individuals in an area of minimum size that provides sufficient resources for the animals so that the population is not at risk of extinction.[7]

According to an IUCN guideline for unspecified animal species, at least 1000 sexually mature individuals are required in an isolated population to ensure its survival and avoid possible inbreeding depression. Connectivity with neighbouring populations has the effect that far fewer individuals are required to avoid inbreeding depression. According to the Guidelines for Management Plans for Large Carnivores at Population Level of the Large Carnivore Initiative for Europe, a division of the IUCN, a population of more than 250 adult wolves may be sufficient to be classified as "Least Concern" if the wolf population in question has connectivity with others in such a way that the immigrants have genetic and demographic effects.[8][9][10][11][12][13]

"Since the object of any conservation planning should be the entire biological unit, i.e. the population, the guidelines recommend an assessment at population level".[14]

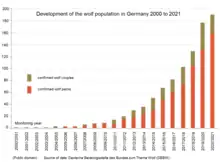

Ilka Reinhardt and Gesa Kluth write in the BfN Script 201 for an independent population: "If one assumes the conservation of 95% of the genetic variation ... is taken as the target value, this means that at least 100 reproducing wolf packs correspond to a favourable conservation status."[15] For example, the German-Western Polish population as a sub-population of the Baltic Population, with the current population in Poland west of the Vistula of at least 95 packs together with five packs belonging to the same sub-population in Germany, would already be in a favourable conservation status, even without the existing exchange with the Baltic and other neighbouring populations.[16] In the monitoring year 2020/21, there were a total of 157 wolf packs registered in Germany.[17]

Wolf monitoring[18] is used to determine the extent to which the genetic exchange between the various wolf populations or subpopulations is taking place again.[19] So today, immigration of wolves from Poland to Germany but also return migration to the east is frequent. Wolves from the Carpathians are migrating into the German-Western Polish population.[20][21] In Bavaria, there were eight records of wolves migrating from the Alpine population in the period 2009 to 2020. In Baden-Württemberg there were five records of wolves from the Alpine and Italian populations in the period 2015 to 2020.[22][23] In September 2020, a wolf (GW 1832 m) from the Alps arrived in the Neckar-Odenwald-Kreis.[24] Individual wolves from the Dinarides-Balkans population have also migrated as far as the German Alpine region.[25][26][27] In early summer 2020 a male wolf (GW 1706 m) from the Dinaric population was detected at Traunstein.[28] The Eastern-, Central-, Western- and Southern European wolf subpopulations are all parts of a rapidly growing Metapopulation.

Situation in Europe

Henryk Okarma said in November 2020 at a conference of the European Parliament: "Although the range of the wolf has increased at least sevenfold since 2006 ... by at least seven times and the number of wolves has increased by four to five times, the conservation status ... was still assessed as unfavourable in the most recent report from 2018. Does this mean that we will have to wait until this species is everywhere before designating a favourable conservation status? until this species is everywhere? If the wolf is everywhere, this can cause conflicts and lead to a decrease in the social acceptance of this species and an increase in illegal actions against wolves. Is such a 'favourable conservation status' then our true conservation goal?"[29]

Commitments of the EU Member States

The EU Member States monitor the conservation status of natural habitats with their priority species and set up a monitoring system to record the listing of animal species listed in Annex II, IV and V and illegal and exceptionally legal killings.[30] The wolf monitoring records serve as feedback to the IUCN, where entries in the Red List are made in appropriate categories,[31] and to the European Commission (Natura 2000).[32] The EU member states are obliged to pass on the current data to the European Commission so that the latter can adapt the protection status in the Habitats Directive accordingly.[33][34] A transfer from the list of strictly protected species in Annex IV of the Habitats Directive to the list of protected species in Annex V requires coordination at federal level with neighbouring countries and requires the approval of the European Commission.

The Habitats Directive does not prescribe any protection measures for the individual habitats, it prescribes no listing in Annex II with Sites of Community Importance,[35] but it requires the guarantee of a favourable conservation status as defined above.[36][37]

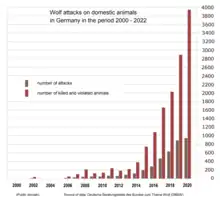

The obligation to provide up-to-date data (beyond the usual six-year cycle for species other than large carnivores derives from Article 16.1.c of the Habitats Directive: "(c) in the interests of public health and public safety, or for other imperative reasons of overriding public interest, including those of a social or economic nature and beneficial consequences of primary importance for the environment;"[38] in this case to save pastoral farming with species-appropriate free-range husbandry, which also fulfils an important function for the preservation of biodiversity in open-land biotopes worthy of protection.

References

- ↑ Large Carnivore Initiative for Europe: Guidelines for Population Level Management Plans for Large Carnivores page 19: "For classifications based on criteria D the appropriate downgrading would imply that if a population has sufficient connectivity to allow enough immigrants to have a demographic impact there would in principle only need to be more than 250 mature individuals in the population for it to be of "least concern"."

- ↑ Europarat: Details of Treaty No. 104

- ↑ D. P. J. Kuijper, E. Sahlén, B. Elmhagen: Paws without claws? Ecological effects of large carnivores in anthropogenic landscapes

- ↑ Biology and ecology of the wolf - potential for expansion Page 19

- ↑ Merill and L. David Mech: The usefulness of GPS telemetry to study wolfcircadian and social activity

- ↑ Maris Hindrikson, Jaanus Remm, Malgorzata Pilot et al.: Wolf population genetics in Europe: a systematic review, meta-analysis and suggestions for conservation and management

- ↑ Luigi Boitani: Wolves: Behavior, Ecology, and Conservationpage 332

- ↑ Large Carnivore Initiative for Europe: pdf Guidelines for Population Level Management Plans for Large Carnivores Page 19: "For classifications based on criteria D the appropriate downgrading would imply that if a population has sufficient connectivity to allow enough immigrants to have a demographic impact there would in principle only need to be more than 250 mature individuals in the population for it to be of "least concern"."

- ↑ Guidelines for Population Level Management Plans for Large Carnivores Archived 2020-10-16 at the Wayback Machine Page 20

- ↑ R. Wayne, P. Hedrick: Genetics and wolf conservation in the American West: Lessons and challenges

- ↑ European Commission Environment: Large carnivores in the EU - the Commission's activity on large carnivores

- ↑ Laikre L, Olsson F. et al.: com/articles/hdy201644 Metapopulation effective size and conservation genetic goals for the Fennoscandian wolf (Canis lupus) population Archived 2013-07-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Guillaume Chapron, Stéphane Legendre et al.: pdf Conservation and control strategies for the wolf (Canis lupus)in western Europe based on demographic models

- ↑ Ilka Reinhardt, Petra Kaczensky, Felix Knauer,Georg Rauer, Gesa Kluth, Sybille Wölflmar, Huckschlag, Ulrich Wotschikowsky: Monitoring von Wolf, Luchs und Bär in Deutschland page 12

- ↑ Life with wolves Guide for dealing with a conflict-prone species in Germany - 2.4. Viable population Page 15 and 16

- ↑ IFAW: Neue Zahlen: Mehr Wolfsrudel in Westpolen

- ↑ DBBW: Wolf territories in Germany - summary by federal states

- ↑ Ilka Reinhardt, Gesa Kluth, Sabina Nowak, Robert W. Mysłajek: Standards for the monitoring of the Central European wolf population in Germany and Poland 2015

- ↑ Maris Hindrikson, Jaanu Remm et al.: Wolf population genetics in Europe: a systematic review, meta-analysis and suggestions for conservation and management

- ↑ Sylwia Czarnomska, Bogumiła Jedrzejewska, Henryk Okarma and others: Concordant mitochondrial and microsatellite DNA structuring between Polish lowland and Carpathian Mountain wolves. Conservation Genetics 14 (3). June 2013, retrieved on 1 July 2015 (PDF; p. 573-588).

- ↑ Freundeskreis freilbender Wölfe: Wolves and Science - Central Poland, a genetic melting pot for wolves

- ↑ Bavarian State Office for the Environment: First records of category C1 wolves in Bavaria 2006 to 2018

- ↑ Ministry for the Environment, Climate and Energy Baden-Württemberg: Clear evidence (C1) of wolves in Baden-Württemberg Archived 2019-04-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Ministry of the Environment, Climate and Energy of Baden-Württemberg: Wolf suspicion in the Neckar-Odenwald-Kreis-confirmed Archived 2020-10-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Management Plan Wolves in Bavaria - Stage 1. StMUGV Munich 2007. Retrieved on 20 January 2018.

- ↑ Management Plan Wolves in Bavaria - Stage 2. Bayerisches Landesamt für Umwelt. Court 2014. Retrieved on 20 January 2018.

- ↑ The return of the wolf to Baden-Württemberg. Guidelines for action for the emergence of individual wolves. Ministry for Rural Areas and Consumer Protection Baden-Württemberg. Stuttgart 2013. Retrieved on 17 January 2018.

- ↑ Bavarian State Office for the Environment: Monitoring of wolves

- ↑ Koexistenz mit Großraubtieren: nächste Schritte zur Erhaltung und Bewirtschaftung

- ↑ Large Carnivore Initiative for Europe: pdf Guidelines for Population Level Management Plans for Large Carnivores page 22

- ↑ IUCN: Canis lupus assessment information

- ↑ Natura 2000: Species of Annexes IV and V of the Fauna Flora Habitats Directive

- ↑ Salvatori, V. and Linnell, J.: pdf Report on the conservation status and threats for wolf (Canis lupus) in Europe Archived 2020-10-24 at the Wayback Machine Council of Europe, Strasbourg 2005

- ↑ European Commission: Conservation Status of large Carnivores

- ↑ The Habitats Directive: Species protection under the Habitats Directive

- ↑ Henryk Okarma, Sven Herzog: Handbuch Wolf. Kosmos, Stuttgart 2019, ISBN 978-3-440-16433-4, page 201.

- ↑ Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora

- ↑ Council Directive 92/43/EEC of 21 May 1992 on the conservation of natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora