| Formation | 1876 |

|---|---|

| Founder | Renaud Oscar d'Adelswärd, Jean-Joseph Labbé |

| Founded at | Longwy, Meurthe-et-Moselle |

| Type | Cartel |

| Legal status | Defunct |

| Purpose | Control iron and steel prices |

Region | Lorraine |

Official language | French |

The Comptoir Métallurgique de Longwy (=Longwy Metal Sales Counter; often only named as “Comptoir de Longwy”) was a cartel of iron smelters seated in Longwy, a town in Lorraine, department Meurthe-et-Moselle, France. In a narrower sense of the term, the ‘Comptoir de Longwy’ was only the ‘’sales agency’’ of the respectively underlying cartel, which also enclosed its member firms and possible other cartel organs. As a legal entity, the Comptoir Métallurgique de Longwy existed from December 10, 1876, to February 1, 1921. It should not be mixed up with the (Société des) Aciéries de Longwy, which was temporarily a member firm of the cartel not earlier than 1880 and survived the cartel up to 1978.

Industrial location and geology

The Comptoir Métallurgique de Longwy was situated in Longwy Bas, which was the productive center of the East-French heavy industry district of the 19th and 20th century. This was true, although Longwy lay at the very north of this region and only some kilometers far from the borders to Belgium, Luxembourg and to the German empire of 1871 to 1918. The development of the heavy industry in Eastern France was triggered by the proximity of both iron ore and coal. Longwy was lying at the northern edge of the Minette district with its extensive iron ore deposits. This area was located almost exclusively in France; only a smaller share of it belonged to the southwest of Luxembourg. Since 1871, the new formed German Empire took a share of Minette by the annexed “German Lorraine”. The supply situation with coal was not as good as with the ore, but viable: Rich coal mines were located in the Prussian Saarland and in Belgium, some also in the initially French and later German Lorraine. Substantial amounts of coal, in particular coke, were obtained from the Rhenish Ruhr district in Germany and from Belgium. Because the Longwy area had no direct connection to navigation, its transportations depended heavily on rail. The success of the iron production in Lorraine was dependent on technology. Because of the high phosphorus content of the ore, the produced pig iron was initially of poor quality and unsuited for many uses. From 1879 on, the smelting process was improved by the Thomas-Gilchrist procedure, which allowed to reduce the embedded phosphorus.

Origin and development by 1914

Iron smelting began in the department Meurthe-et-Moselle in 1834. In Longwy Bas, the first blast furnace was established not earlier than in 1848. Generally, the number and the size of the smelting firms in the region had increased, which led to a more vigorous competition.[1] In the mid-1870s, the French industry was affected by an economic baisse. Thus, on 10 December 1876, owners of four iron smelting establishments founded the Comptoir Metallurgique de Longwy as a common device to operate their sales. This type of organization was not novel for the French economy; nevertheless, the Comptoir de Longwy was the first joint sales organization of the French iron and steel industry.[2] Another comptoir was founded in Nancy in 1879, but was soon absorbed by the rival establishment in Longwy.[3] By this, the Nancy area became the second productive area of the cartel. In 1891, the member firms of the Comptoir de Longwy comprised 12 factories with 31 blast furnaces. By the end of the 19th century, the comptoir controlled 30% of pig iron produced in Meurthe et Moselle while having 14 members. It had an effective monopoly of sales to metallurgical companies that did not make their own pig iron.[3] In 1899-1900, there was a crisis in the supply of coke from Belgium and Westphalia.[4] In response, the comptoir installed a battery of coke ovens at Auby beside the Deule canal that could produce 250,000 tons, rising to 500,000 tons the next year.[5]

Organizational structure

Internally, the Comptoir de Longwy consisted of three main bodies:

- the member assembly, which negotiated and decided upon all important issues (Article 7-16 Status de 1905).

- the executive director (“Directeur-gérant”), who was elected by the member assembly. This office could be given to an adherent of a member firm or to external personalities (Article 17).

- a supervisory commissioner („Commissaire de surveillance“), who was to be appointed every year (Article 20). His duty was a comprehensive auditing of the commercial society by checking all its accounts and inventories.

Membership

The number of members varied over the time span. This was because of the entries of new participants, mergers between them and exits from the cartel. Also the quality of the members changed: Over the decades, there was a development from pure smelters with concessions of ore exploitation to combined establishments of smelting and further processing.

The members of 1876

The Comptoir Metallurgique de Longwy was founded by the four heavy industrialist Jean-Joseph Labbé, Baron Oscar d’Adelswärd (1811–98), Theophile Ziane und Gustave Raty.[1] These entrepreneurs led pure smelting establishments, which sold their whole output to industrial further processors. Two of the cartel founders – Labbé and Adelswärd in 1880 merged possessions of themselves to create the Aciéries de Longwy, which was only sometimes, not constantly a regular member of the Comptoir de Longwy.

The changes of the 1880s and 1890s

In 1891, the Comptoir comprised 12 establishments, by the end of the 19th century, it had 14 members.

The members of 1904

The member firms of the state of 1904 can be displayed by the following list:[6]

- Métallurgique de Gorcy

- Marc Raty et Cie. Hussigny

- Métallurgique de Senelle-Maubeuge

- F. de Saintignon et Cie, Longwy

- Métallurgique d’Aubrives et Villerupt

- Lorraine Industrielle (siege: Nancy, usine: Hussigny)

- Des Hauts-Fourneaux de la Chiers

- Des Hauts-Fourneaux et Forges de Villerupt Laval-Dieu

- Compagnie des Forges de Châtillon, Commentry et Neuves Maisons

- Des Forges et Fonderies de Montataire

- Des Hauts-Fourneaux et Aciéries de Pompey

- Des Hauts-Fourneaux de Maxéville

- Compagnie des Forges et Aciéries de la Marine et d’Homécourt

- Des Hauts-Fourneaux et Fonderies de Pont-à-Mousson

Most of these firms had their industrial activities within the department of Meurthe et Moselle. However, this area featured not so much one integrated business region, but rather two: the surroundings of Longwy-Bas on the one hand (true for no. 1, 2, 4 to 9) and that of Nancy on the other hand (true for no. 11 to 14). Four companies (No. 3, 5, 9 and 10) had premises far away from the axis Longwy-Nancy: No. 9 comprised with “Commentry” a location ca. 590 km south of Longwy near the Massif Central. No. 10 had its plants in “Montataire”, ca. 320 km west of Longwy in the Paris region. No. 3 and 5 had premises 210 km or, respectively, 130 km in the west near the Belgian south border.

Three cartel members (no. 5, 9 and 13) consisted of two or three remote business units mentioned in their company names: No. 5 was active in the Longwy area as well as in Aubrives 130 km in the west; each No. 9 and 13 had locations near Longwy and Nancy, while No. 13 additionally comprised a site far off in the south (“Commentry”).

The informal members

A speciality of the Comptoir de Longwy was the existence of hidden, i.e. only informal members.[1] In 1913, the seven associated firms reached the half of the number of the regular participants:

- Forges et Acieries du Nord et de l’Est, Jarville

- Laminoirs, Hauts Fourneaux, Forges, Fonderies et Usines de la Providence, Réhon

- Hauts Fourneaux, Forges et Acieries de Pompey

- Acieries de Micheville

- Forges et Acieries de la Marine et d’Homecourt

- Societe des Aciéries de Longwy

- de Wendel et Cie, Jœuf, Hayingen

These firms had their business in the narrower area of the department Meurthe et Moselle, that is to say: the surroundings of Longwy (true for no. 2, 4 to 7) and Nancy (true for no. 1, 3 and 5).

From World War I to 1921

Already at the beginning of WWI, in August 1914, the region of Longwy Bas was partly destroyed by German bombardment. The industrial structures were set out of function and further production was almost impossible. During the war, German heavy industrialist like Hermann Röchling dismantled still operable machines and installations. In late 1918, the French responded on this with postcards of the ruins and the comment “Le Départ des Boche”. The reconstruction of the blast furnaces and the reestablishment of the supply lines took at least to 1920.[7] In 1921, by consent of the member assembly on January 21, 1921, the Comptoir de Longwy was formally terminated effective for February 1.[8] Due to the war events and results, the economic environment had strongly changed: The French gains of the formerly German Eastern Lorraine and of the now occupied Sarre region brought along a lot of new competitors. Also in the old territories, outsider competition came up: Firms formerly being loyal informal members of the cartel began selling below the comptoir prices. Some companies even cancelled their long existing membership to do this. A strong motivation for this came from the war demolitions: The French state was reluctant to compensate the enterprises for this quickly, and so the firms sold off their ore stocks to be able to finance the necessary repairs.[9] The failure of the Comptoir de Longwy was also a failure of the newly founded Comptoir Sidérurgique de la France. This had been established soon after the end of the war on January 16, 1919. The latter was designed as a general cartel organizing and fostering sub-cartels for distinct product groups.[10] In this concept, the Comptoir de Longwy had been designated for a national instead of a regional approach of regulating the pig iron production.

Aims and functions

The purpose of the Comptoir de Longwy was the sales of pig iron that was produced by its members and not needed for exportation or further processing by them. During the late 19th century and early 20th century the Comptoir had a virtual monopoly on the pig iron market of Eastern France. The cartel administration allocated shares of domestic sales to each of its members. The effects of this means is disputed since long. While some authors suggested a control almost as by setting production quotas,[11] other scholars expressed doubts about such a far reaching impact. The Comptoir de Longwy proved sustainable despite some serious internal tensions.[12] This was an achievement, since in neighboring Germany and Belgium the iron cartels had been more prone to conflicts and disruptions.

Marketing and advertising

The Comptoir de Longwy made some efforts to get more attention and notice in the business world. This was limited to the sales of pig iron, while for by-products and further manufactured products the member firms took the initiative, so for instance in 1889 the Acieries de Longwy for slag phosphate. So the advertising of the Comptoir had to be more general and mediate. At the Paris Exposition Universelle (1900) the Comptoir showed an elegant salon decorated with paintings by Édouard Rosset-Granger that mainly depicted the picturesque aspects of iron ore mining, although one showed the casting of a blast furnace. At the 1909 Exposition Internationale de l'Est de la France in Nancy the booth held three large paintings by Rosset-Granger that were usually hung in the Comptoir's directorial office. They represented exploitation of Côte Rouge ore, a view of a blast furnace and a casting of metal.[13]

Cost reduction and balancing of demand and supply

The operation of Comptoir led to sustained economies, which was internationally recognized. It reduced the sales cost by 15-20 French centimes per ton.[14] This could have been between 2 and 30% of the product value ex works depending on the value of the chosen pig iron sort (prices of 1904).

From an American point of view, economies by cartels were of particular interest. In June 1916 Edward N. Hurley, vice chairman of the US Federal Trade Commission, summarized the opinions and findings on this in front of an audience of the American Iron and Steel Institute. He said,

”Official Government investigations in several European countries make it clear that cartels have succeeded in reducing both the cost of production and the selling expenses, which permits the consumer to purchase the finished product at a lower figure. In the case of the French Comptoir de Longwy, cooperation in selling has reduced selling expenses to from 3 to 4 [U.S.] cents per ton. It is maintained that the cartel organization also enables manufacturers to equalize supply and demand, to adapt their prices to demand, and to regulate the prices of their products in accordance with the cost of raw materials.”[15]

Leadership and personnel

The Comptoir de Longwy was led and operated by a qualified management staff, which was true for the representatives of the member firms as well as for externally acquired professionals. Both went hand in hand: By its founders, the Comptoir had four experienced entrepreneurs, in particular Baron Renaud Oscar d' Adelswärd (1811–98) and Jean-Joseph Labbé. Effective for 1877, they made Alexandre Dreux to the first executive director. Dreux was a poor farmer's son who made a remarkable career: Initially, he worked as a clerk at a foundry in Le Mans, then as an accountant for the foundry owner Armand Chappée, who recommended him.[16][lower-alpha 1] In 1888 Alexandre Dreux became the Director General of the Aciéries de Longwy.[17] In the Comptoir, he was succeeded by Philippe Aubé as the managing director.[3] The geologist and industrialist Georges Rolland (1852–1910) worked as an administrator of the Comptoir métallurgique de Longwy, around and after 1900.[18] In 1909, Rémi Jacquemart (1860-1909) of the Société métallurgique d'Aubrives et Villerupt became administrating director of the Comptoir, but died soon after.[19] Count Fernand de Saintignon (1846–1921) of the Société des Aciéries de Longwy was often found in the role of the president (of the member assembly) of the Comptoir Métallurgique de Longwy.[20] Nevertheless, for the membering entrepreneurs their functions in the Comptoir were only of secondary importance in comparison to their own ventures.

Social and capital relationships

The foundry entrepreneurs of French Lorrain had the consciousness of a distinct group, but were open for the entrance of technical specialists.[21] These industrialists, including their families, also run their private lives predominantly with each other. By personal, kinship, professional and capital relationships they were intensely interconnected. The iron companies of French Lorraine were also linked by mutual interest to those of neighboring countries. On the eve of World War I (1914–18) eight of the seventeen directors of the comptoir represented German or Belgian companies.[22]

Political and scientific opinions about the Comptoir

The Comptoir de Longwy was the subject of a heated but inconclusive debate in the Chamber of Deputies in July 1891 about whether the cartel caused any damage.[23] The socialist deputy Jean Jaurès attacked the pricing fixing practices of the comptoir, which was defended by the moderate right Jules Méline. Jaurès noted that Méline was opposed to labour unions, but saw nothing wrong with a cartel of manufacturers.[24] The trade-unionist Alphonse Merrheim publicized the power that the Comptoir de Longwy and the Comité des Forges exerted in breaking strikes.[25] However, two well-publicized court cases in 1902 confirmed that the Comptoir was acting legally.[3] In the scientific and economic-political debates of around 1900, the Comptoir de Longwy was regarded as a prototype cartel of the French economy.[26] This was not only true for the domestic, inner-French setting, but also for the discussions in the Anglosphere and in the German speaking countries. So, renowned cartel authors of that epoch like the German Robert Liefmann or the American James Jeans respectfully mentioned this organization.[27][28] In France, authors like Paul de Rousiers, P. Obrin and Étienne Martin Saint-Léon[29] more or less concentrated on this entrepreneurial union. For the French economic politician Jules Méline, the Comptoir de Longwy was the most efficient French cartel (but regrettably not as efficient as German cartels).[30] Even among the Socialists, the Comptoir de Longwy was known: In 1914, the Austrian Otto Bauer mentioned it as an example of cartelization by raw material monopolization.[31]

Headquarters and material remains

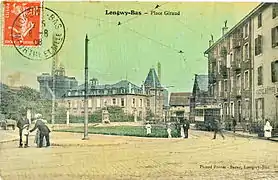

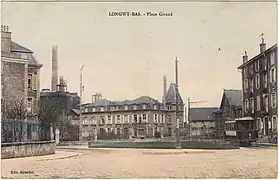

Comptoir building in the center of Place Giraud. Longwy Bas, pre-1914

Comptoir building in the center of Place Giraud. Longwy Bas, pre-1914 Comptoir building in the center of Place Giraud. Longwy Bas, pre-1914

Comptoir building in the center of Place Giraud. Longwy Bas, pre-1914 Former Comptoir building from the frontside left, 2017

Former Comptoir building from the frontside left, 2017 Former Comptoir building from the frontside right, 2017

Former Comptoir building from the frontside right, 2017 Former Comptoir building from the backside, 2017

Former Comptoir building from the backside, 2017

In its first association contracts (“statuts”), the seat of the Comptoir had been designated with “Longwy, Meurthe et Moselle” only. From 1905 on, you find two additional specifications; it is now determined as “Longwy Bas” and “Place Giraud”. ‘Longwy Bas’ was the industrial quarter of the town Longwy, where the blast furnaces were standing. ‘Place Giraud’ was a central location within Longwy Bas in proximity of the railway station. In postcards stamped in 1908 and later, you find a handsome (new?) building at this spot presented as a sight of the community. To some extent, this construction has survived up to the present, but is in a poor and unprotected condition.

Notes

- ↑ Adelswärd controlled the Usine du Prieuré of Mont-Saint-Martin and the concession of the iron mines of Herserange.

- 1 2 3 Bühler 1934, p. 26.

- ↑ Moine 1990, p. 71.

- 1 2 3 4 Smith 2006, p. 322.

- ↑ Léon 1902, p. 69.

- ↑ Léon 1902, p. 70.

- ↑ Obrin 1908, p. 54.

- ↑ Aciéries de Longwy – industrie.lu.

- ↑ Bühler 1934, p. 152.

- ↑ Bühler 1934, p. 151.

- ↑ Bühler 1934, pp. 152, 267, 309.

- ↑ Smith 2006, p. 321.

- ↑ Moine 1987, p. 10.

- ↑ Paul Édouard Rosset-Granger.

- ↑ Baumgarten & Meszlény 1906, p. 171.

- ↑ Hurley 1916, p. 6.

- ↑ Smith 2006, p. 341.

- ↑ Moine 1987, p. 8.

- ↑ Leger 2017, p. 1.

- ↑ Longwy (Comptoir Métallurgique) – Patrons.

- ↑ Guillet 1921, p. 240.

- ↑ Moine 1989.

- ↑ Jackson 2013, p. 72.

- ↑ Assemblée nationale 1891, p. 1095.

- ↑ Jaurès 2016, PT190.

- ↑ Monatte 1925.

- ↑ Leonhardt 2018, pp. 43, 48/49.

- ↑ Liefmann 1903, p. 679.

- ↑ Jeans 1906, p. 198.

- ↑ Martin Saint-Léon 1903, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Méline 1903, p. XIII.

- ↑ Bauer 1914, p. 20.

Main literature

- Comptoir Métallurgique de Longwy: Status [de 1892, 1905, 1909]. Longwy or Paris.

- Obrin, P. (1908): Le Comptoir métallurgique de Longwy. Paris: Giard & Brière.

- Rousiers, Paul de (1901): Les syndicats industriels de producteurs en France et à l'étranger. Trusts-Cartells-Comptoirs. Paris: Colin, p. 196–256.

- Rousiers, Paul de (1912): Les syndicats industriels de producteurs en France et à l'Étranger. Trusts-Cartells-Comptoirs-Ententes internationales. Paris: Colin, p. 173-217.

- Bühler, Rolf (1934): Die Roheisenkartelle in Frankreich. Ihre Entstehung, Entwicklung und Bedeutung von 1876 bis 1934. Zürich: Girsberger, p. 142-172.

Additional sources

- "Aciéries de Longwy", industrie.lu - D'Industriegeschicht vu Lëtzebuerg

- Assemblée nationale (1891), Annales de la Chambre des députés: débats parlementaires (in French), Impr. du Journal Officiel., retrieved 2017-10-29

- Bauer, Otto (1914), Die Teuerung. In: Internationaler Sozialistenkongress in Wien (23. bis 29. August 1914). Dokumente. 2. Kommission. Wien, 23. bis 29. August. (in German), Brussels

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Baumgarten, Ferdinand; Meszlény, Artur (1906), Kartelle und Trusts. Ihre Stellung im Wirtschafts- und Rechtssystem der wichtigsten Kulturstaaten. Eine nationalökonomisch-juristische Studie (in German), Berlin/Budapest: Liebmann

- Bühler, Rolf (1934), Die Roheisenkartelle in Frankreich. Ihre Entstehung, Entwicklung und Bedeutung von 1876 bis 1934 (in German), Zürich

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Guillet, L. (April 1921), "Notice Biographique : Comte Fernand de Saintignon" (PDF), Revue de la métallurgie (in French), no. 4, retrieved 2017-07-22

- Hurley, Edward N. (1916), Cooperation and Efficiency in Developing Our Foreign Trade (PDF), Government Printing Office, retrieved 2017-10-29

- Jackson, Peter (2013-12-05), Beyond the Balance of Power: France and the Politics of National Security in the Era of the First World War, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-78303-4, retrieved 2017-10-29

- Jaurès, Jean (2016-11-23), Oeuvres: Bloc des gauches (in French), Fayard, ISBN 978-2-213-70349-7, retrieved 2017-10-29

- Jeans, James S. (1906), The Iron Trade of Great Britain, London: Methuen

- Leger, Alain Y. (22 July 2017), "Société agricole et industrielle du Sud-Algérien (SAISA)" (PDF), Les entreprises coloniales françaises (in French), retrieved 2017-07-30

- Léon, Paul (1902), "Le canal du Nord-Est" (PDF), Annales de Géographie (in French), 11 (55), retrieved 2017-10-29

- Leonhardt, Holm A. (2018), The Development of Cartel Theory between 1883 and the 1930s - from International Diversity to Convergence, retrieved 2019-04-28

- Liefmann, Robert (1903), "Neuere französische Kartelliteratur", Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik 26 (3. Folge) (in German)

- "Longwy (Comptoir Métallurgique)", Patrons de France (in French), retrieved 2017-10-29

- Martin Saint-Léon, Étienne (1903), Cartells et trusts (in French), Paris: Lecoffre

- Méline, Jules (1903), "Preface", Francis Laur: Les cartels et syndicats en Allemagne. Essai documentaire. De l'accaparement. Bd. 2. (in French), Préface par Jules Méline, Paris: Publ. scient. & industr.

- Moine, Jean-Marie (16 October 1987), Les Maîtres de Forges en Lorraine du Milieu du Xixe Siècle aux Années Trente (PDF) (Doctoral thesis in History, Université de Nancy II) (in French), retrieved 2017-10-29

- Moine, Jean-Marie (1989), Les barons du fer. Les maîtres de forges en Lorraine du milieu du 19e siècle aux années trente, histoire sociale d'un patronat sidérurgique (in French), Metz: Serpenoise

- Moine, Jean-Marie (1990), "Une aristocratie industrielle : les maîtres de forges en Lorraine" (PDF), Romantisme (in French), 20 (70. La noblesse): 69–79, doi:10.3406/roman.1990.5700, retrieved 2017-10-29

- Monatte, Pierre (November 1925), "Alphonse Merrheim", La Révolution prolétarienne (11), retrieved 2017-10-29

- Obrin, P. (1908), Le Comptoir métallurgique de Longwy (in French), Paris: Giard & Brière.

- Paul Édouard Rosset-Granger (in French), 22 October 2016, retrieved 2017-10-29

- Savoye, Antoine (1988), "Paul de Rousiers, sociologue et praticien du syndicalisme", Cahiers Georges Sorel (in French), 6 (1): 52–77, doi:10.3406/mcm.1988.959

- Smith, Michael Stephen (2006), The Emergence of Modern Business Enterprise in France, 1800-1930, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-01939-3, retrieved 2017-07-17