| Comedo | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Plural: comedones[1] |

| |

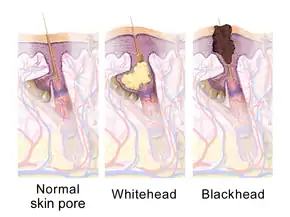

| Illustration comparing a normal skin pore with a whitehead and a blackhead | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

A comedo is a clogged hair follicle (pore) in the skin.[2] Keratin (skin debris) combines with oil to block the follicle.[3] A comedo can be open (blackhead) or closed by skin (whitehead) and occur with or without acne.[3] The word "comedo" comes from the Latin comedere, meaning "to eat up", and was historically used to describe parasitic worms; in modern medical terminology, it is used to suggest the worm-like appearance of the expressed material.[1]

The chronic inflammatory condition that usually includes comedones, inflamed papules, and pustules (pimples) is called acne.[3][4] Infection causes inflammation and the development of pus.[2] Whether a skin condition classifies as acne depends on the number of comedones and infection.[4] Comedones should not be confused with sebaceous filaments.

Comedo-type ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is not related to the skin conditions discussed here. DCIS is a noninvasive form of breast cancer, but comedo-type DCIS may be more aggressive, so may be more likely to become invasive.[5]

Causes

Oil production in the sebaceous glands increases during puberty, causing comedones and acne to be common in adolescents.[3][4] Acne is also found premenstrually and in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome.[3] Smoking may worsen acne.[3]

Oxidation rather than poor hygiene or dirt causes blackheads to be black.[2] Washing or scrubbing the skin too much could make it worse, by irritating the skin.[2] Touching and picking at comedones might cause irritation and spread infection.[2] What effect shaving has on the development of comedones or acne is unclear.[2]

Some skin products might increase comedones by blocking pores,[2] and greasy hair products (such as pomades) can worsen acne.[3] Skin products that claim to not clog pores may be labeled noncomedogenic or nonacnegenic.[6] Make-up and skin products that are oil-free and water-based may be less likely to cause acne.[6] Whether dietary factors or sun exposure make comedones better, worse, or neither is unknown.[3]

A hair that does not emerge normally, an ingrown hair, can also block the pore and cause a bulge or lead to infection (causing inflammation and pus).[4]

Genes may play a role in the chances of developing acne.[3] Comedones may be more common in some ethnic groups.[3][7] People of Latino and recent African descent may experience more inflammation in comedones, more comedonal acne, and earlier onset of inflammation.[3][7]

Pathophysiology

Comedones are associated with the pilosebaceous unit, which includes a hair follicle and sebaceous gland. These units are mostly on the face, neck, upper chest, shoulders, and back.[3] Excess keratin combined with sebum can plug the opening of the follicle.[3][8] This small plug is called a microcomedo.[8] Androgens increase sebum (oil) production.[3] If sebum continues to build up behind the plug, it can enlarge and form a visible comedo.[8]

A comedo may be open to the air ("blackhead") or closed by skin ("whitehead").[2] Being open to the air causes oxidation of the melanin pigment, which turns it black.[9][2] Cutibacterium acnes is the suspected infectious agent in acne.[3] It can proliferate in sebum and cause inflamed pustules (pimples) characteristic of acne.[3] Nodules are inflamed, painful, deep bumps under the skin.[3]

Comedones that are 1 mm or larger are called macrocomedones.[10] They are closed comedones and are more frequent on the face than neck.[11]

Solar comedones (sometimes called senile comedones) are related to many years of exposure to the sun, usually on the cheeks, not to acne-related pathophysiology.[12]

Management

Using nonoily cleansers and mild soap may not cause as much irritation to the skin as regular soap.[13][14] Blackheads can be removed across an area with commercially available pore-cleansing strips (which can still damage the skin by leaving the pores wide open and ripping excess skin) or the more aggressive cyanoacrylate method used by dermatologists.[15]

Squeezing blackheads and whiteheads can remove them, but can also damage the skin.[2] Doing so increases the risk of causing or transmitting infection and scarring, as well as potentially pushing any infection deeper into the skin.[2] Comedo extractors are used with careful hygiene in beauty salons and by dermatologists, usually after using steam or warm water.[2]

Complementary medicine options for acne in general have not been shown to be effective in trials.[3] These include aloe vera, pyridoxine (vitamin B6), fruit-derived acids, kampo (Japanese herbal medicine), ayurvedic herbal treatments, and acupuncture.[3]

Some acne treatments target infection specifically, but some treatments are aimed at the formation of comedones, as well.[16] Others remove the dead layers of the skin and may help clear blocked pores.[2][3][4]

Dermatologists can often extract open comedones with minimal skin trauma, but closed comedones are more difficult.[3] Laser treatment for acne might reduce comedones,[17] but dermabrasion and laser therapy have also been known to cause scarring.[10]

Macrocomedones (1 mm or larger) can be removed by a dermatologist using surgical instruments or cauterized with a device that uses light.[10][11] The acne drug isotretinoin can cause severe flare-ups of macrocomedones, so dermatologists recommend removal before starting the drug and during treatment.[10][11]

Some research suggests that the common acne medications retinoids and azelaic acid are beneficial and do not cause increased pigmentation of the skin.[18] If using a retinoid, sunscreen is recommended.

Rare conditions

Favre–Racouchot syndrome occurs in sun-damaged skin and includes open and closed comedones.[19]

Nevus comedonicus or comedo nevus is a benign hamartoma (birthmark) of the pilosebaceous unit around the oil-producing gland in the skin.[20] It has widened open hair follicles with dark keratin plugs that resemble comedones, but they are not actually comedones.[20][21]

Dowling–Degos disease is a genetic pigment disorder that includes comedo-like lesions and scars.[22][23]

Familial dyskeratotic comedones are a rare autosomal-dominant genetic condition, with keratotic (tough) papules and comedo-like lesions.[24][25]

References

- 1 2 "Comedo". Oxford Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on December 21, 2013. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Informed Health Online. "Acne". Fact sheet. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Williams, HC; Dellavalle, RP; Garner, S (Jan 28, 2012). "Acne vulgaris". Lancet. 379 (9813): 361–72. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60321-8. PMID 21880356. S2CID 205962004.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Purdy, Sarah; De Berker, David (2011). "Acne vulgaris". BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2011: 1714. PMC 3275168. PMID 21477388.

- ↑ National Cancer Institute (2002). "Breast cancer treatment". Physician Desk Query. National Cancer Institute. PMID 26389187. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- 1 2 British Association of Dermatologists. "Acne". Patient information leaflet. British Association of Dermatologists. Archived from the original on 2013-10-04. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- 1 2 Davis, EC; Callender, VD (April 2010). "A review of acne in ethnic skin: pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, and management strategies". The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology. 3 (4): 24–38. PMC 2921746. PMID 20725545.

- 1 2 3 Burkhart, CG; Burkhart, CN (October 2007). "Expanding the microcomedone theory and acne therapeutics: Propionibacterium acnes biofilm produces biological glue that holds corneocytes together to form plug". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 57 (4): 722–4. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.05.013. PMID 17870436.

- ↑ Kumar, Vinay; Abbas, Abul K.; Aster, Jon C.; Turner, Jerrold R.; Perkins, James A.; Robbins, Stanley L.; Cotran, Ramzi S., eds. (2021). Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (10th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier. p. 1165. ISBN 978-0-323-53113-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Wise, EM; Graber, EM (November 2011). "Clinical pearl: comedone extraction for persistent macrocomedones while on isotretinoin therapy". The Journal of Clinical and Aesthetic Dermatology. 4 (11): 20–1. PMC 3225139. PMID 22132254.

- 1 2 3 Primary Care Dermatology Society. "Acne: macrocomedones". Clinical Guidance. Primary Care Dermatology Society. Retrieved 12 June 2013.

- ↑ DermNetNZ. "Solar comedones". New Zealand Dermatological Society. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ↑ Poli, F (Apr 15, 2002). "[Cosmetic treatments and acne]". La Revue du Praticien. 52 (8): 859–62. PMID 12053795.

- ↑ Korting, HC; Ponce-Pöschl, E; Klövekorn, W; Schmötzer, G; Arens-Corell, M; Braun-Falco, O (Mar–Apr 1995). "The influence of the regular use of a soap or an acidic syndet bar on pre-acne". Infection. 23 (2): 89–93. doi:10.1007/bf01833872. PMID 7622270. S2CID 39430391.

- ↑ Pagnoni, A; Kligman, AM; Stoudemayer, T (1999). "Extraction of follicular horny impactions the face by polymers. Efficacy and safety of a cosmetic pore-cleansing strip (Bioré)". Journal of Dermatological Treatment. 10 (1): 47–52. doi:10.3109/09546639909055910.

- ↑ Gollnick, HP; Krautheim, A (2003). "Topical treatment in acne: current status and future aspects". Dermatology. 206 (1): 29–36. doi:10.1159/000067820. PMID 12566803. S2CID 11179291.

- ↑ Orringer, JS; Kang, S; Hamilton, T; Schumacher, W; Cho, S; Hammerberg, C; Fisher, GJ; Karimipour, DJ; Johnson, TM; Voorhees, JJ (Jun 16, 2004). "Treatment of acne vulgaris with a pulsed dye laser: a randomized controlled trial". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 291 (23): 2834–9. doi:10.1001/jama.291.23.2834. PMID 15199033.

- ↑ Woolery-Lloyd, HC; Keri, J; Doig, S (Apr 1, 2013). "Retinoids and azelaic Acid to treat acne and hyperpigmentation in skin of color". Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 12 (4): 434–7. PMID 23652891.

- ↑ Rapini, Ronald P.; Bolognia, Jean L.; Jorizzo, Joseph L. (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. p. 1847. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- 1 2 Zarkik, S; Bouhllab, J; Methqal, A; Afifi, Y; Senouci, K; Hassam, B (Jul 15, 2012). "Keratoacanthoma arising in nevus comedonicus". Dermatology Online Journal. 18 (7): 4. doi:10.5070/D38XZ7951S. PMID 22863626.

- ↑ DermNetNZ. "Comedo Naevus". New Zealand Dermatological Society. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- ↑ Bhagwat, PV; Tophakhane, RS; Shashikumar, BM; Noronha, TM; Naidu, V (Jul–Aug 2009). "Three cases of Dowling Degos disease in two families" (PDF). Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology. 75 (4): 398–400. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.53139. PMID 19584468.

- ↑ Khaddar, RK; Mahjoub, WK; Zaraa, I; Sassi, MB; Osman, AB; Debbiche, AC; Mokni, M (January 2012). "[Extensive Dowling-Degos disease following long term PUVA therapy]". Annales de Dermatologie et de Vénéréologie. 139 (1): 54–7. doi:10.1016/j.annder.2011.10.403. PMID 22225744.

- ↑ Hallermann, C; Bertsch, HP (Jul–Aug 2004). "Two sisters with familial dyskeratotic comedones". European Journal of Dermatology. 14 (4): 214–5. PMID 15319152.

- ↑ OMIM. "Comedones, familial dyskeratotic". OMIM database. OMIM. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

External links

- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). . Encyclopedia Americana.

- What causes blackheads, Treatment and Prevention Archived 2020-01-27 at the Wayback Machine