Province of Angola Província de Angola | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1575–1975 | |||||||||||||||

| Anthem: "Hymno Patriótico" (1808–34) Patriotic Anthem "Hino da Carta" (1834–1910) Hymn of the Charter "A Portuguesa" (1910–75) The Portuguese | |||||||||||||||

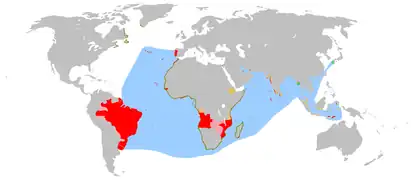

Portuguese West Africa in 1905–1975 | |||||||||||||||

| Status | Colony of the Portuguese Empire (1575–1951) Overseas Province of Portugal (1951–1972) State of the Portuguese Empire (1972–1975) | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Luanda | ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Portuguese (official) Umbundu, Kimbundu, Kikongo, Chokwe | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism[1] Protestantism Traditional religions | ||||||||||||||

| Government | Colonial government | ||||||||||||||

| Head of State | |||||||||||||||

• 1575–78 | King Sebastian I of Portugal | ||||||||||||||

• 1974–75 | President Francisco da Costa Gomes | ||||||||||||||

| Governor General | |||||||||||||||

• 1575–1589 | Paulo Dias de Novais[2] | ||||||||||||||

• 1975 | Leonel Alexandre Gomes Cardoso | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Imperialism | ||||||||||||||

• Establishment of Luanda | 1575 | ||||||||||||||

• Independence of Angola | 11 November 1975 | ||||||||||||||

| Currency | Portuguese real (1575-1911) Portuguese escudo (1911–14) Angolan escudo (1914–28; 1958–77) Angolan angolar (1926–58) | ||||||||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | AO | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Angola | ||||||||||||||

| History of Angola | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||

| Post-war Angola’s | ||||||||||||||||

| See also | ||||||||||||||||

| Years in Angola | ||||||||||||||||

Portuguese Angola refers to Angola during the historic period when it was a territory under Portuguese rule in southwestern Africa. In the same context, it was known until 1951 as Portuguese West Africa (officially the State of West Africa).

Initially ruling along the coast and engaging in military conflicts with the Kingdom of Kongo, in the 18th century Portugal gradually managed to colonise the interior Highlands. Full control of the entire territory was not achieved until the beginning of the 20th century, when agreements with other European powers during the Scramble for Africa fixed the colony's interior borders. On 11 June 1951, its name was changed to the Overseas Province of Angola and in 1973, the State of Angola. In 1975, Portuguese Angola became the independent People's Republic of Angola.

History

The history of Portuguese presence on the territory of contemporary Angola lasted from the arrival of the explorer Diogo Cão in 1484[3] until the decolonisation of the territory in November 1975. Over these five centuries, several different situations existed.

Colony

When Diogo Cão and other explorers reached the Kongo Kingdom at the end of the 15th century, Angola as such did not exist. Its present territory comprised a number of separate peoples, some organized as kingdoms or tribal federations of varying sizes. The Portuguese were interested in trade, principally in slaves. They therefore maintained a peaceful and mutually profitable relationship with the rulers and nobles of the Kongo Kingdom. Kings such as João I and Afonso I studied Christianity and learned Portuguese, in turn Christianising their nation and sharing the benefits from the slave trade. The Portuguese established small trading posts on the lower Congo, in the area of the present Democratic Republic. A more important trading settlement on the Atlantic coast was erected at Soyo in the territory of the Kongo Kingdom. It is now Angola's northernmost town, apart from the Cabinda exclave.

In 1575, the settlement of Luanda was established on the coast south of the Kongo Kingdom, and in the 17th century the settlement of Benguela, even farther to the south. From 1580 to the 1820s, well over a million people from present-day Angola were exported as slaves to the New World, mainly to Brazil, but also to North America.[4] According to Oliver and Atmore, "for 200 years, the colony of Angola developed essentially as a gigantic slave-trading enterprise".[5] Portuguese sailors, explorers, soldiers and merchants had a long-standing policy of conquest and establishment of military and trading outposts in Africa with the conquest of Muslim-ruled Ceuta in 1415 and the establishment of bases in present-day Morocco and the Gulf of Guinea. The Portuguese had Catholic beliefs and their military expeditions included from the very beginning the conversion of foreign peoples.

In the 17th century, conflicting economic interests led to a military confrontation with the Kongo Kingdom. Portugal defeated the Kongo Kingdom in the Battle of Mbwila on 29 October, 1665, but suffered a disastrous defeat at the Battle of Kitombo when they tried to invade Kongo in 1670. Control of most of the central highlands was achieved in the 18th century. Further reaching attempts at conquering the interior were undertaken in the 19th century.[6] However, full Portuguese administrative control of the entire territory was not achieved until the beginning of the 20th century.

In 1884, the United Kingdom, which up to that time refused to acknowledge that Portugal possessed territorial rights north of Ambriz, concluded a treaty recognising Portuguese sovereignty over both banks of the lower Congo. However, the treaty, meeting with opposition there and in Germany, was not ratified. Agreements concluded with the Congo Free State, the German Empire and France in 1885–1886 fixed the limits of the province, except in the south-east, where the frontier between Barotseland (north-west Rhodesia) and Angola was determined by an Anglo-Portuguese agreement of 1891 and the arbitration award of King Vittorio Emanuele III of Italy in 1905.[3]

During the period of Portuguese colonial rule of Angola, cities, towns and trading posts were founded, railways were opened, ports were built, and a Westernised society was being gradually developed, despite the deep traditional tribal heritage in Angola which the minority European rulers were neither willing nor interested in eradicating. From the 1920s, Portugal's administration showed an increasing interest in developing Angola's economy and social infrastructure.[7]

Between 1939 and 1943 the Portuguese army carried out operations against the nomadic Mucubal people, accused of rebellion, which led to the death of half their population. The survivors were incarcerated in concentration camps, sent to forced labor camps, where the great majority of them perished due to the brutality of the work system, undernourishment and executions.[8]

The beginning of the war

In 1951, the Portuguese Colony of Angola became an overseas province of Portugal. In the late 1950s the National Front for the Liberation of Angola (FNLA) and the People's Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) began to organize strategies and action plans to fight Portuguese rule and the remunerated system which affected many of the native African people from the countryside, who were relocated from their homes and made to perform compulsory work, almost always unskilled hard labour, in an environment of economic boom. Organised guerrilla warfare began in 1961, the same year that a law was passed to improve the working conditions of the largely unskilled native workforce, which was demanding more rights. In 1961, the Portuguese Government indeed abolished a number of basic legal provisions which discriminated against black people, like the Estatuto do Indigenato (Decree-Law 43: 893 of 6 September 1961). However, the conflict, conversely known as the Colonial War or the War of Liberation, erupted in the North of the territory when UPA rebels based in Republic of the Congo massacred both white and black civilians in surprise attacks in the countryside. After visiting the United Nations, rebel leader Holden Roberto returned to Kinshasa and organised Bakongo militants.[9]

Holden Roberto launched an incursion into Angola on 15 March 1961, leading 4,000 to 5,000 militants. His forces took farms, government outposts, and trading centres, killing everyone they encountered. At least 1,000 whites and an unknown number of blacks were killed.[10] Commenting on the incursion, Roberto said, "this time the slaves did not cower". They massacred everything.[11] The effective military in Angola were composed of approximately 6,500 men: 5,000 black Africans and 1,500 white Europeans sent from Portugal. After these events the Portuguese Government, under the dictatorial Estado Novo regime of António de Oliveira Salazar and later Marcelo Caetano, sent thousands of troops from Europe to perform counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations. In 1963 Holden Roberto established the Revolutionary Government of Angola in Exile (Portuguese: Governo revolucionário de Angola no exílio, GRAE) in Kinshasa in an attempt to claim on the international scene the sole representation of forces fighting Portuguese rule in Angola. The National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) also started pro-independence guerrilla operations in 1966. Despite the overall military superiority of the Portuguese Army in the Angolan theatre, the independence guerrilla movements were never fully defeated. However, by 1972, after the Frente Leste, a successful military campaign in the East of Angola, complemented by a pragmatic hearts and minds policy, the military conflict in Angola was effectively won for the Portuguese.

From 1966 to 1970, the pro-independence guerrilla movement MPLA expanded their previously limited insurgency operations to the East of Angola. This vast countryside area was far away from the main urban centres and close to foreign countries where the guerrillas were able to take shelter. The UNITA, a smaller pro-independence guerrilla organisation established in the East, supported the MPLA. Until 1970, the combined guerrilla forces of MPLA and UNITA in the East Front were successful in pressuring Portuguese Armed Forces (FAP) in the area to the point that the guerrillas were able to cross the Cuanza River and could threaten the territory of Bié, which included an important urban centre in the agricultural, commercial and industrial town of Silva Porto. In 1970, the guerrilla movement decided to reinforce the Eastern Front by relocating troops and armament from the North to the East.

Campaign in the Eastern Front

In 1971, the FAP started a successful counter-insurgency military campaign that expelled the three guerrilla movements operating in the East to beyond the frontiers of Angola. The last guerrillas lost hundreds of soldiers and left tons of equipment behind, disbanding chaotically to neighbouring countries or, in some cases, joining or surrendering to the Portuguese. In order to gain the confidence of the local rural populations, and to create conditions for their permanent and productive settlement in the region, the Portuguese authorities organised massive vaccination campaigns, medical check-ups, and water, sanitation and alimentary infrastructure as a way to better contribute to the economic and social development of the people and dissociate the population from the guerrillas and their influence. On 31 December 1972, the Development Plan of the East (Plano de Desenvolvimento do Leste) included in its first stage 466 development enterprises (150 were completed and 316 were being built). Nineteen health centres had been built and 26 were being constructed. 51 new schools were operating and 82 were being constructed[12][13]

Federated state

In June 1972, the Portuguese National Assembly approved a new version of its Organic Law on Overseas Territories, in order to grant its African overseas territories a wider political autonomy and to tone down the increasing dissent both internally and abroad. It changed Angola's status from an overseas province to an “autonomous state” with authority over some internal affairs, while Portugal was to retain responsibility for defense and foreign relations. However, the intent was by no means to grant Angolan independence, but was instead to "win the hearts and minds" of the Angolans, convincing them to remain permanently a part of an intercontinental Portugal. Renaming Angola (like Mozambique) in November 1972 (in effect 1 January 1973)[14] "Estado" (state) was part of an apparent effort to give the Portuguese Empire a sort of federal structure, conferring some degree of autonomy to the "states". In fact, the structural changes and increase in autonomy were extremely limited. The government of the "State of Angola" was the same as the old provincial government, except for some cosmetic changes to personnel and titles. As in Portugal itself, the government of the "State of Angola" was entirely composed of people aligned with the Estado Novo regime's establishment. While these changes were taking place, a few guerrilla nuclei stayed active inside the territory, and continued to campaign outside of Angola against Portuguese rule. The idea of having the independence movements take part in the political structure of the revamped territory's organization was absolutely unthinkable (on both sides).[15]

Carnation Revolution and independence

However, the Portuguese authorities were unable to defeat the guerrillas as a whole during the Portuguese Colonial War, particularly in Portuguese Guinea, and suffered heavy casualties in the 13 years of conflict. Throughout the war Portugal faced increasing dissent, arms embargoes and other punitive sanctions from most of the international community. The war was becoming even more unpopular in Portuguese society due to its length and costs, the worsening of diplomatic relations with other United Nations members, and the role it played as a factor in the perpetuation of the Estado Novo regime. It was this escalation that would lead directly to the mutiny of members of the FAP in the Carnation Revolution of April 1974 – an event that would lead to the independence of all of the former Portuguese colonies in Africa.

.jpg.webp)

On 25 April 1974, the Portuguese Government of the Estado Novo regime under Marcelo Caetano, the corporatist and authoritarian regime established by António de Oliveira Salazar that had ruled Portugal since the 1930s, was overthrown in the Carnation Revolution, a military uprising in Lisbon. In May of that year, the Junta de Salvação Nacional (the new revolutionary government of Portugal) proclaimed a truce with the pro-independence African guerrillas in an effort to promote peace talks and independence.[16] The military-led coup returned democracy to Portugal, ending the unpopular Colonial War where hundreds of thousands of Portuguese soldiers had been conscripted into military service, and replacing the authoritarian Estado Novo (New State) regime and its secret police which repressed elemental civil liberties and political freedoms. It started as a professional class[17] protest of Portuguese Armed Forces captains against the 1973 decree law Dec. Lei n.o 353/73.[18][19]

These events prompted a mass exodus of Portuguese citizens, overwhelmingly white but some mestiço (mixed race) or black, from Portugal's African territories, creating hundreds of thousands destitute refugees — the retornados.[20] Angola became a sovereign state on 11 November 1975 in accordance with the Alvor Agreement and the newly independent country was proclaimed the People's Republic of Angola.

Government

.svg.png.webp)

In the 20th century, Portuguese Angola was subject to the Estado Novo regime. In 1951, the Portuguese authorities changed the statute of the territory from a colony to an overseas province of Portugal. Legally, the territory was as much a part of Portugal as Lisbon but as an overseas province enjoyed special derogations to account for its distance from Europe. Most members of the government of Angola were from Portugal, but a few were Angolan. Nearly all members of the bureaucracy were from Portugal, as most Angolans did not have the necessary qualifications to obtain positions.

The government of Angola, as it was in Portugal, was highly centralised. Power was concentrated in the executive branch, and all elections where they occurred were carried out using indirect methods. From the Prime Minister's office in Lisbon, authority extended down to the most remote posts of Angola through a rigid chain of command. The authority of the government of Angola was residual, primarily limited to implementing policies already decided in Europe. In 1967, Angola also sent a number of delegates to the National Assembly in Lisbon.

The highest official in the province was the governor-general, appointed by the Portuguese cabinet on recommendation of the Overseas Minister. The governor-general had both executive and legislative authority. A Government Council advised the governor-general in the running of the province. The functional cabinet consisted of five secretaries appointed by the Overseas Minister on the advice of the governor. A Legislative Council had limited powers and its main activity was approving the provincial budget. Finally, an Economic and Social Council had to be consulted on all draft legislation, and the governor-general had to justify his decision to Lisbon if he ignored its advice.

In 1972, the Portuguese National Assembly changed Angola's status from an overseas province to an “autonomous state” with authority over some internal affairs; Portugal was to retain responsibility for defense and foreign relations. Elections were held in Angola for a legislative assembly in 1973.[16]

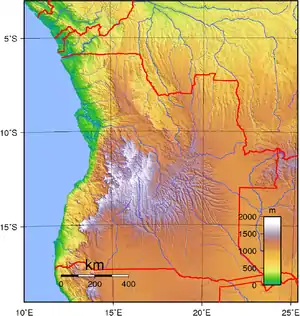

Geography

Portuguese Angola was a territory covering 1,246,700 km2, an area greater than France and Spain put together. It had 5,198 km of terrestrial borders and a coastline with 1,600 km. Its geography was diverse. From the coastal plain, ranging in width from 25 kilometres in the south to 100–200 kilometers in the north, the land rises in stages towards the high inland plateau covering almost two-thirds of the country, with an average altitude of between 1,200 and 1,600 metres. Angola's two highest peaks were located in these central highlands. They were Moco Mountain (2,620 m) and Meco Mountain (2,538 m).

Most of Angola's rivers rose in the central mountains. Of the many rivers that drain to the Atlantic Ocean, the Cuanza and Cunene were the most important. Other major streams included the Kwango River, which drains north to the Congo River system, and the Kwando and Cubango Rivers, both of which drain generally southeast to the Okavango Delta. As the land drops from the plateau, many rapids and waterfalls plunge downward in the rivers. Portuguese Angola had no sizable lakes, besides those formed by dams and reservoirs built by the Portuguese administration.

The Portuguese authorities established several national parks and natural reserves across the territory: Bicauri, Cameia, Cangandala, Iona, Mupa, Namibe and Quiçama. Iona was Angola's oldest and largest national park, it was proclaimed as a reserve in 1937 and upgraded to a national park in 1964.

Angola was indeed a territory that underwent a great deal of progress after 1950. The Portuguese government built dams, roads, schools, etc. There was also an economic boom that led to a huge increase of the European population. The white population increased from 44,083 in 1940 to 172,529 in 1960. With around 1,000 immigrants arriving each month. On the eve of the end of the colonial period, the ethnic European residents numbered 400,000 (1974) (excluding enlisted and commissioned soldiers from the mainland) and the mixed race population was at around 100,000 (many were Cape Verdian migrants working in the territory). The total population was around 5.9 million at that time.

Luanda grew from a town of 61,208 with 14.6% of those inhabitants being white in 1940, to a major cosmopolitan city of 475,328 in 1970 with 124,814 Europeans (26.3%) and around 50,000 mixed race inhabitants. Most of the other large cities in Angola had around the same ratio of Europeans at the time, with the exception of Sá da Bandeira (Lubango), Moçâmedes (Namibe) and Porto Alexandre (Tombua) in the south where the white population was more established. All of these cities had European majorities from 50% to 60%.

The capital of the territory was Luanda,[21][22] officially called São Paulo de Luanda. Other cities and towns were:[23]

- Porto Amboim

- Vila Teixeira da Silva

- São Felipe de Benguela[24]

- Vila Robert Williams

- Duque de Bragança

- Vila General Machado

- Vila João de Almeida

- Vila Mariano Machado

- Nova Lisboa[25]

- Silva Porto

- Vila da Ponte

- Lobito[26]

- Sá da Bandeira[27]

- Vila Luso

- Malanje[28]

- Forte República

- São Salvador do Congo

- Serpa Pinto

- Moçâmedes[29]

- Vila Salazar

- Vila Pereira d'Eça

- Vila Henrique de Carvalho

- Santo António do Zaire

- Novo Redondo

- Porto Alexandre

- Carmona[30]

The exclave of Cabinda was to the north.[31] Portuguese Congo (Cabinda) was established a Portuguese protectorate by the 1885 Treaty of Simulambuco. Sometime during the 1920s, it became incorporated into the larger colony (later the overseas province) of Portuguese Angola. The two colonies had initially been contiguous, but later became geographically separated by a narrow corridor of land, which Portugal ceded to Belgium, allowing the Belgian Congo access to the Atlantic Ocean. Following the decolonisation of Portuguese Angola with the 1975 Alvor Agreement, the short-lived Republic of Cabinda unilaterally declared its independence. However, Cabinda was soon overpowered and re-annexed by the newly proclaimed People's Republic of Angola and never achieved international recognition.

Economy

Portuguese explorers and settlers founded trading posts and forts along the coast of Africa beginning in the 15th century, and reached the Angolan coast in the 16th. Portuguese explorer Paulo Dias de Novais founded Luanda in 1575 as "São Paulo de Loanda", and the region developed a slave trade with the help of local Imbangala and Mbundu peoples, who were notable slave hunters. Trade was mostly with the Portuguese colony of Brazil in the New World. Brazilian ships were the most numerous in the ports of Luanda and Benguela. By this time, Angola, a Portuguese colony, was in fact more like a colony of Brazil, another Portuguese colony. A strong Brazilian influence was also exercised by the Jesuits in religion and education.[32]

The philosophy of war gradually gave way to the philosophy of trade. The great trade routes and the agreements that made them possible were the driving force for activities between the different areas; warlike states become states ready to produce and to sell.[32] In the Planalto, or high plains, the most important states were those of Bié and Bailundo, the latter being noted for its production of foodstuffs and rubber. The colonial power, Portugal, becoming ever richer and more powerful, would not tolerate the growth of these neighbouring states and subjugated them one by one, enabling Portuguese hegemony over much of the area. During the period of the Iberian Union (1580–1640), Portugal lost influence and power and made new enemies. The Dutch, a major enemy of Castile, invaded many Portuguese overseas possessions, including Luanda. The Dutch ruled Luanda from 1640 to 1648 as Fort Aardenburgh. They were seeking black slaves for use in sugarcane plantations of Northeastern Brazil (Pernambuco, Olinda and Recife), which they had also seized from Portugal. John Maurice, Prince of Nassau-Siegen, conquered the Portuguese possessions of Saint George del Mina, Saint Thomas, and Luanda on the west coast of Africa. After the dissolution of the Iberian Union in 1640, Portugal reestablished its authority over the lost territories of the Portuguese Empire.[32]

The Portuguese started to develop townships, trading posts, logging camps, and small processing factories. From 1764 onwards, there was a gradual change from a slave-based society to one based on production for domestic consumption and export. Brazil became independent in 1822 and the slave trade was abolished in 1836. In 1844, Angola's ports were opened to legal foreign shipping. By 1850, Luanda was one of the most developed cities outside Europe in the Portuguese Empire: it was full of trading companies, exporting (together with Benguela) palm and peanut oil, wax, copal, timber, ivory, cotton, coffee, and cocoa, among many other products. Maize, tobacco, dried meat and cassava flour also began to be produced locally. The Angolan bourgeoisie was born.[32] From the 1920s to the 1960s, strong economic growth, abundant natural resources and development of infrastructure, led to the arrival of even more Portuguese settlers from the metropole.[32]

Diamond mining began in 1912, when the first gems were discovered by Portuguese prospectors in a stream of the Lunda region, in the northeast. In 1917 the Companhia de Diamantes de Angola (Diamang) was granted the concession for diamond mining and prospecting in Portuguese Angola. Diamang had exclusive mining and labor procurement rights in a huge concession in Angola and used this monopoly to become the colony's largest commercial operator and also its leading revenue generator. Its wealth was generated by African laborers, many of whom were forcibly recruited to work on the mines with Lunda's aggressive state-company recruitment methods (See also chivalo/shibalo).[33] Work was done with shovels into the 1970s, and as late as 1947, the company saw no benefit to mechanizing its operations, because local labour was so inexpensive.[33] Even the voluntary contract workers, or contratados, were exploited and had to build their own housing and often cheated of their wages. However Diamang, which was exempt from taxes, grew affluent in the 1930s and also realized that in a remote area like Lunda, the supply of workers was not inexhaustible and so the workers there were somewhat better treated than on some of the other mines or on the sugar plantations.

On the whole African laborers performed brutal work in poor conditions for very little pay that they were frequently cheated of. The American sociologist Edward Ross visited rural Angola in 1924 on behalf of the Temporary Slavery Commission of the League of Nations and wrote a scathing report describing the labor system as "virtually state serfdom", that did not allow Africans time to produce their own food. In addition, when their wages were embezzled and they were denied access to the colonial judicial system.[34]

From the mid-1950s until 1974, iron ore was mined in Malanje, Bié, Huambo, and Huíla provinces, and production reached an average of 5.7 million tons per year between 1970 and 1974. Most of the iron ore was shipped to Japan, West Germany, and the United Kingdom, and earned almost US$50 million a year in export revenue. During 1966–67 a major iron ore terminal was built by the Portuguese at Saco, the bay just 12 km North of Moçâmedes (Namibe). The client was the Compania Mineira do Lobito, the Lobito Mining Company, which developed an iron ore mine inland at Cassinga. The construction of the mine installations and a 300 km railway were commissioned to Krupp of Germany and the modern harbour terminal to SETH, a Portuguese company owned by Højgaard & Schultz of Denmark. The small fishing town of Moçâmedes hosted construction workers, foreign engineers and their families for two years. The Ore Terminal was completed on time within one year and the first 250,000 ton ore carrier docked and loaded with ore in 1967.[29][35] The Portuguese discovered petroleum in Angola in 1955. Production began in the Cuanza basin in the 1950s, in the Congo basin in the 1960s, and in the exclave of Cabinda in 1968. The Portuguese government granted operating rights for Block Zero to the Cabinda Gulf Oil Company, a subsidiary of ChevronTexaco, in 1955. Oil production surpassed the exportation of coffee as Angola's largest export in 1973.

By the early 1970s, a variety of crops and livestock were produced in Portuguese Angola. In the north, cassava, coffee, and cotton were grown; in the central highlands, maize was cultivated; and in the south, where rainfall is lowest, cattle herding was prevalent. In addition, there were large plantations run by Portuguese that produced palm oil, sugarcane, bananas, and sisal. These crops were grown by commercial farmers, primarily Portuguese, and by peasant farmers, who sold some of their surplus to local Portuguese traders in exchange for supplies. The commercial farmers were dominant in marketing these crops, however, and enjoyed substantial support from the overseas province's Portuguese government in the form of technical assistance, irrigation facilities, and financial credit. They produced the great majority of the crops that were marketed in Angola's urban centres or exported for several countries.[36]

Fishing in Portuguese Angola was a major and growing industry. In the early 1970s, there were about 700 fishing boats, and the annual catch was more than 300,000 tons. Including the catch of foreign fishing fleets in Angolan waters, the combined annual catch was estimated at over 1 million tons. The Portuguese territory of Angola was a net exporter of fish products, and the ports of Moçâmedes, Luanda and Benguela were among the most important fishing harbours in the region.

Education

Non-urban black African access to educational opportunities was very limited for most of the colonial period, most were not able to speak Portuguese and did not have knowledge of Portuguese culture and history.[37] Until the 1950s, educational facilities run by the Portuguese colonial government were largely restricted to the urban areas.[37] Responsibility for educating rural Africans were commissioned by the authorities to several Roman Catholic and Protestant missions based across the vast countryside, which taught black Africans in Portuguese language and culture.[37] As a consequence, each of the missions established its own school system, although all were subject to ultimate control and support by the Portuguese.[37]

In mainland Portugal, the homeland of the colonial authorities who ruled in the territory from the 16th century until 1975, by the end of the 19th century the illiteracy rates were at over 80 percent and higher education was reserved for a small percentage of the population. 68.1 percent of mainland Portugal's population was still classified as illiterate by the 1930 census. Mainland Portugal's literacy rate by the 1940s and early 1950s was low by North American and Western European standards at the time. Only in the 1960s did the country make public education available for all children between the ages of six and twelve, and the overseas territories profited from this new educational developments and change in policy at Lisbon.

Starting in the early 1950s, the access to basic, secondary and technical education was expanded and its availability was being increasingly opened to both the African indigenes and the ethnic Portuguese of the territories. Education beyond the primary level became available to an increasing number of black Africans since the 1950s, and the proportion of the age group that went on to secondary school in the early 1970s was an all-time record high enrolment.[37] Primary school attendance was also growing substantially.[37] In general, the quality of teaching at the primary level was acceptable, even with instruction carried on largely by black Africans who sometimes had substandard qualifications.[37] Most secondary school teachers were ethnically Portuguese, especially in the urban centers.[37]

Two state-run university institutions were founded in Portuguese Africa in 1962 by the Portuguese Ministry of the Overseas Provinces headed by Adriano Moreira—the Estudos Gerais Universitários de Angola in Portuguese Angola and the Estudos Gerais Universitários de Moçambique in Portuguese Mozambique—awarding a wide range of degrees from engineering to medicine.[38] In the 1960s, the Portuguese mainland had four public universities, two of them in Lisbon (which compares with the 14 Portuguese public universities today). In 1968, the Estudos Gerais Universitários de Angola was renamed Universidade de Luanda (University of Luanda).

Sports

From the 1940s onward, city and town expansion and modernization included the construction of several sports facilities for football, rink hockey, basketball, volleyball, handball, athletics, gymnastics and swimming. Several sports clubs were founded across the entire territory, among them were some of the largest and oldest sports organizations of Angola. Several sportsmen, especially football players, that achieved wide notability in Portuguese sports were from Angola. José Águas, Rui Jordão and Jacinto João were examples of that, and excelled in the Portugal national football team. Since the 1960s, with the latest developments on commercial aviation, the highest ranked football teams of Angola and the other African overseas provinces of Portugal, started to compete in the Taça de Portugal (the Portuguese Cup). Other facilities and organizations for swimming, nautical sports, tennis and wild hunting became widespread. Beginning in the 1950s, motorsport was introduced to Angola. Sport races were organized in cities like Nova Lisboa, Benguela, Sá da Bandeira and Moçâmedes. The International Nova Lisboa 6 Hours sports car race became noted internationally.[39]

Football became very popular in Angola during the 20th century. Football was mostly spread to Angola by the Portuguese people who settled in the colonies. This was mostly due to the fact that immigration to the colonies was encouraged, both Angola and Mozambique saw an influx of Portuguese migrants. Football became very popular in Angola and people started to follow teams that were from the Portuguese mainland. In the latter half of the 20th century, Portugal would recruit many players form Angola. Miguel Arcanjo was one such player who played in Portugal. The colonial players would help Portuguese teams win many championships.[40]

Famous people

See also

- Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino (archives in Lisbon documenting Portuguese Empire, including Angola)

- Estado Novo (Portugal)

- History of Angola

- List of colonial governors of Angola

- Portuguese Cape Verde

- Portuguese Guinea

- Portuguese Mozambique

- Portuguese São Tomé and Príncipe

Notes

- ↑ James, Martin W. (2004). Historical Dictionary of Angola. Scarecrow Press. p. 140. ISBN 9780810865600.

- ↑ as Captain-Governor

- 1 2 Chisholm 1911.

- ↑ Joseph C. Miller, Way of Death: Merchant Capitalism and the Angolan Slave Trade, 1730–1830, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988

- ↑ Medieval Africa, 1250–1800 (pp174) By Roland Anthony Oliver, Anthony Atmore

- ↑ René Pélissier, Les guerres grises. Résistance et revoltes en Angola (1845–1941), Montamets/Orgeval: self-published, 1977

- ↑ More Power to the People, 2006.

- ↑ Rafael Coca de Campos Kakombola. O genocídio dos Mucubais na Angola colonial, 1930-1943, Ponta Grossa, 2021.

- ↑ Tvedten, Inge (1997). Angola: Struggle for Peace and Reconstruction. p. 31.

- ↑ Edgerton, Robert Breckenridge (2002). Africa's Armies: From Honor to Infamy. Westview Press. p. 72. ISBN 9780813339474.

- ↑ Walker, John Frederick (2004). A Certain Curve of Horn: The Hundred-Year Quest for the Giant Sable Antelope of Angola. p. 143. ISBN 9780802140685.

- ↑ (in Portuguese) António Pires Nunes, Angola Vitória Militar no Leste

- ↑ António Pires Nunes, Angola, 1966–74: vitória militar no leste, ISBN 9728563787, 9789728563783, Publisher: Prefácio, 2002

- ↑ Jorge Bacelar Gouveia (September–December 2017). "The Constitutionalism of Angola and its 2010 Constitution". Revista de Estudos Constitucionais, Hermenêutica e Teoria do Direito (RECHTD) 9(3). pp. 221–239. Retrieved 28 October 2020. (in Portuguese)

- ↑ John A. Marcum, The Angolan Revolution, vol. II, Exile Politics and Guerrilla Warfare (1962–1976), Cambridge/Mass. & London, MIT Press, 1978

- 1 2 Angola, History, The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th ed. Copyright © 2007, Columbia University Press

- ↑ (in Portuguese) Cronologia: Movimento dos capitães, Centro de Documentação 25 de Abril, University of Coimbra

- ↑ (in Portuguese) Arquivo Electrónico: Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho, Centro de Documentação 25 de Abril, University of Coimbra

- ↑ (in Portuguese) A Guerra Colonial na Guine/Bissau (07 de 07), Otelo Saraiva de Carvalho on the Decree Law, RTP 2 television, youtube.com.

- ↑ Dismantling the Portuguese Empire, Time Magazine (Monday, 7 July 1975) NB: The figures in this source are too high, as the total number of whites in the colonies did not reach 700,000.

- ↑ Angola antes da Guerra, a film of Luanda, Portuguese Angola (before 1975), youtube.com

- ↑ LuandaAnosOuro.wmv, a film of Luanda, Portuguese Angola (before 1975), youtube.com

- ↑ Angola no outro lado do tempo 🇦🇴, Angola – O Outro Lado do Tempo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=33x7u7Ijm7Y&list=PLZWwV_k3xAIaium0MhHB-6bhu9BX2OP8S&t=1s

- ↑ BenguelaAnosOuro.wmv, a film of Benguela, Overseas Province of Angola, before 1975.

- ↑ NovaLisboaAnosOuro.wmv, a film of Nova Lisboa, Overseas Province of Angola, before 1975.

- ↑ LobitoAnosOuro.wmv, a film of the Lobito in Portuguese Angola, before independence from Portugal.

- ↑ SáDaBandeiraAnosOuro.wmv, a film of Sá da Bandeira, Overseas Province of Angola, before 1975.

- ↑ MalanjeAnosOuro.wmv, a film of Malanje, Overseas Province of Angola (before 1975).

- 1 2 (in Portuguese) Angola de outros tempos Moçamedes, Moçâmedes under Portuguese rule before 1975, youtube.com

- ↑ Angola-Carmona (Viagem ao Passado)-Kandando Angola, a film of Carmona, Portuguese Angola (before 1975).

- ↑ CabindaAnosOuro.wmv, a film of Cabinda, Portuguese Angola (before 1975).

- 1 2 3 4 5 History of Angola Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Republic of Angola Embassy in the United Kingdom

- 1 2 Todd Cleveland (2015). Diamonds in the Rough: Corporate Paternalism and African Professionalism on the Mines of Colonial Angola, 1917–1975. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0821445211.

- ↑ Jeremy Ball (2006). ""I escaped in a coffin": Remembering Angolan Forced Labor from the 1940s". Cadernos de Estudos Africanos (9/10): 61–75. doi:10.4000/cea.1214. Retrieved 15 May 2016.

- ↑ (in Portuguese) Angola – Moçâmedes, minha terra, eu te vi crescer... (Raul Ferreira Trindade), history of Moçâmedes/Namibe

- ↑ Louise Redvers, POVERTY-ANGOLA: NGOs Sceptical of Govt’s Rural Development Plans Archived 12 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine, [Inter Press Service News Agency] (6 June 2009)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Warner, Rachel. "Conditions before Independence". A Country Study: Angola (Thomas Collelo, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (February 1989). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ (in Portuguese) 52. UNIVERSIDADE DE LUANDA

- ↑ 6h Huambo 1973, Nova Lisboa Internacional Sports Race

- ↑ Cleveland, Todd (2017). Following the Ball : The Migration of African Soccer Players Across the Portuguese Colonial Empire, 1949–1975. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-89680-499-9.

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Angola". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 38–40.

Bibliography

- Gerardo Augusto Pery, ed. (1875). "Angola". Geographia e estatistica geral de Portugal e colonias (in Portuguese). Lisbon: Imprensa Nacional.

- Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (9th ed.). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 45.

- Esteves Pereira; Guilherme Rodrigues, eds. (1904). "Angola". Portugal: Diccionario Historico... (in Portuguese). Vol. 1. Lisbon: Joao Romano Torres. hdl:2027/gri.ark:/13960/t2x38qb1f. OCLC 865826167 – via HathiTrust.

.svg.png.webp)