A lighthouse is a tower, building, or other type of physical structure designed to emit light from a system of lamps and lenses and to serve as a beacon for navigational aid, for maritime pilots at sea or on inland waterways.

Lighthouses mark dangerous coastlines, hazardous shoals, reefs, rocks, and safe entries to harbors; they also assist in aerial navigation. Once widely used, the number of operational lighthouses has declined due to the expense of maintenance and has become uneconomical since the advent of much cheaper, more sophisticated and effective electronic navigational systems.

History

Ancient lighthouses

Before the development of clearly defined ports, mariners were guided by fires built on hilltops. Since elevating the fire would improve visibility, placing the fire on a platform became a practice that led to the development of the lighthouse.[1] In antiquity, the lighthouse functioned more as an entrance marker to ports than as a warning signal for reefs and promontories, unlike many modern lighthouses. The most famous lighthouse structure from antiquity was the Pharos of Alexandria, Egypt, which collapsed following a series of earthquakes between 956 CE and 1323 CE.

The intact Tower of Hercules at A Coruña, Spain gives insight into ancient lighthouse construction; other evidence about lighthouses exists in depictions on coins and mosaics, of which many represent the lighthouse at Ostia. Coins from Alexandria, Ostia, and Laodicea in Syria also exist.

Modern construction

The modern era of lighthouses began at the turn of the 18th century, as the number of lighthouses being constructed increased significantly due to much higher levels of transatlantic commerce. Advances in structural engineering and new and efficient lighting equipment allowed for the creation of larger and more powerful lighthouses, including ones exposed to the sea. The function of lighthouses was gradually changed from indicating ports to the providing of a visible warning against shipping hazards, such as rocks or reefs.

The Eddystone Rocks were a major shipwreck hazard for mariners sailing through the English Channel.[2] The first lighthouse built there was an octagonal wooden structure, anchored by 12 iron stanchions secured in the rock, and was built by Henry Winstanley from 1696 to 1698. His lighthouse was the first tower in the world to have been fully exposed to the open sea.[3]

The civil engineer John Smeaton rebuilt the lighthouse from 1756 to 1759;[4] his tower marked a major step forward in the design of lighthouses and remained in use until 1877. He modeled the shape of his lighthouse on that of an oak tree, using granite blocks. He rediscovered and used "hydraulic lime", a form of concrete that will set under water used by the Romans, and developed a technique of securing the granite blocks together using dovetail joints and marble dowels.[5] The dovetailing feature served to improve the structural stability, although Smeaton also had to taper the thickness of the tower towards the top, for which he curved the tower inwards on a gentle gradient. This profile had the added advantage of allowing some of the energy of the waves to dissipate on impact with the walls. His lighthouse was the prototype for the modern lighthouse and influenced all subsequent engineers.[6]

One such influence was Robert Stevenson, himself a seminal figure in the development of lighthouse design and construction.[7] His greatest achievement was the construction of the Bell Rock Lighthouse in 1810, one of the most impressive feats of engineering of the age. This structure was based upon Smeaton's design, but with several improved features, such as the incorporation of rotating lights, alternating between red and white.[8] Stevenson worked for the Northern Lighthouse Board for nearly fifty years[7] during which time he designed and oversaw the construction and later improvement of numerous lighthouses. He innovated in the choice of light sources, mountings, reflector design, the use of Fresnel lenses, and in rotation and shuttering systems providing lighthouses with individual signatures allowing them to be identified by seafarers. He also invented the movable jib and the balance-crane as a necessary part for lighthouse construction.

Alexander Mitchell designed the first screw-pile lighthouse – his lighthouse was built on piles that were screwed into the sandy or muddy seabed. Construction of his design began in 1838 at the mouth of the Thames and was known as the Maplin Sands lighthouse, and first lit in 1841.[9] Although its construction began later, the Wyre Light in Fleetwood, Lancashire, was the first to be lit (in 1840).[9]

Lighting improvements

Until 1782 the source of illumination had generally been wood pyres or burning coal. The Argand lamp, invented in 1782 by the Swiss scientist Aimé Argand revolutionized lighthouse illumination with its steady smokeless flame. Early models used ground glass which was sometimes tinted around the wick. Later models used a mantle of thorium dioxide suspended over the flame, creating a bright, steady light.[10] The Argand lamp used whale oil, colza, olive oil[11] or other vegetable oil as fuel, supplied by a gravity feed from a reservoir mounted above the burner. The lamp was first produced by Matthew Boulton, in partnership with Argand, in 1784, and became the standard for lighthouses for over a century.[12]

South Foreland Lighthouse was the first tower to successfully use an electric light in 1875. The lighthouse's carbon arc lamps were powered by a steam-driven magneto.[13] John Richardson Wigham was the first to develop a system for gas illumination of lighthouses. His improved gas 'crocus' burner at the Baily Lighthouse near Dublin was 13 times more powerful than the most brilliant light then known.[14]

The vaporized oil burner was invented in 1901 by Arthur Kitson, and improved by David Hood at Trinity House. The fuel was vaporized at high pressure and burned to heat the mantle, giving an output of over six times the luminosity of traditional oil lights. The use of gas as illuminant became widely available with the invention of the Dalén light by Swedish engineer Gustaf Dalén. He used Agamassan (Aga), a substrate, to absorb the gas, allowing the gas to be stored, and hence used, safely. Dalén also invented the 'sun valve', which automatically regulated the light and turned it off during the daytime. The technology was the predominant light source in lighthouses from the 1900s to the 1960s, when electric lighting had become dominant.[15]

Optical systems

With the development of the steady illumination of the Argand lamp, the application of optical lenses to increase and focus the light intensity became a practical possibility. William Hutchinson developed the first practical optical system in 1763, known as a catoptric system. This rudimentary system effectively collimated the emitted light into a concentrated beam, thereby greatly increasing the light's visibility.[16] The ability to focus the light led to the first revolving lighthouse beams, where the light would appear to the mariners as a series of intermittent flashes. It also became possible to transmit complex signals using the light flashes.

French physicist and engineer Augustin-Jean Fresnel developed the multi-part Fresnel lens for use in lighthouses. His design allowed for the construction of lenses of large aperture and short focal length, without the mass and volume of material that would be required by a lens of conventional design. A Fresnel lens can be made much thinner than a comparable conventional lens, in some cases taking the form of a flat sheet. A Fresnel lens can also capture more oblique light from a light source, thus allowing the light from a lighthouse equipped with one to be visible over greater distances.

The first Fresnel lens was used in 1823 in the Cordouan lighthouse at the mouth of the Gironde estuary; its light could be seen from more than 20 miles (32 km) out.[17] Fresnel's invention increased the luminosity of the lighthouse lamp by a factor of four and his system is still in common use.

Modern lighthouses

The introduction of electrification and automatic lamp changers began to make lighthouse keepers obsolete. For many years, lighthouses still had keepers, partly because lighthouse keepers could serve as a rescue service if necessary. Improvements in maritime navigation and safety such as satellite navigation systems such as GPS led to the phasing out of non-automated lighthouses across the world.[18] In Canada, this trend has been stopped and there are still 50 staffed light stations, with 27 on the west coast alone.[19]

Remaining modern lighthouses are usually illuminated by a single stationary flashing light powered by solar-charged batteries mounted on a steel skeleton tower.[20] Where the power requirement is too great for solar power, cycle charging by diesel generator is used: to save fuel and to increase periods between maintenance the light is battery powered, with the generator only coming into use when the battery has to be charged.[21]

Famous lighthouse builders

John Smeaton is noteworthy for having designed the third and most famous Eddystone Lighthouse, but some builders are well known for their work in building multiple lighthouses. The Stevenson family (Robert, Alan, David, Thomas, David Alan, and Charles) made lighthouse building a three-generation profession in Scotland. Richard Henry Brunton designed and built 26 Japanese lighthouses in Meiji Era Japan, which became known as Brunton's "children".[22] Blind Irishman Alexander Mitchell invented and built a number of screw-pile lighthouses. Englishman James Douglass was knighted for his work on the fourth Eddystone Lighthouse.[23]

United States Army Corps of Engineers Lieutenant George Meade built numerous lighthouses along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts before gaining wider fame as the winning general at the Battle of Gettysburg. Colonel Orlando M. Poe, engineer to General William Tecumseh Sherman in the siege of Atlanta, designed and built some of the most exotic lighthouses in the most difficult locations on the U.S. Great Lakes.[24]

French merchant navy officer Marius Michel Pasha built almost a hundred lighthouses along the coasts of the Ottoman Empire in a period of twenty years after the Crimean War (1853–1856).[25]

Technology

In a lighthouse, the source of light is called the "lamp" (whether electric or fuelled by oil) and the light is concentrated, if needed, by the "lens" or "optic". Power sources for lighthouses in the 20th–21st centuries vary.

Power

Originally lit by open fires and later candles, the Argand hollow wick lamp and parabolic reflector were introduced in the late 18th century.

Whale oil was also used with wicks as the source of light. Kerosene became popular in the 1870s and electricity and carbide (acetylene gas) began replacing kerosene around the turn of the 20th century.[20] Carbide was promoted by the Dalén light which automatically lit the lamp at nightfall and extinguished it at dawn.

In the second half of the 20th century, many remote lighthouses in Russia (then Soviet Union) were powered by radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs). These had the advantage of providing power day or night and did not need refuelling or maintenance. However, after the collapse of the Soviet government in 1990s, most of the official records on the locations, and condition, of these lighthouses were reportedly lost.[26] Over time, the condition of RTGs in Russia degraded; many of the fell victim to vandalism and scrap metal thieves, who may not have been aware of the dangerous radioactive contents.[27]

Energy-efficient LED lights can be powered by solar panels, with batteries instead of a diesel generator for backup.[28]

Light source

Many Fresnel lens installations have been replaced by rotating aerobeacons which require less maintenance.

In modern automated lighthouses, the system of rotating lenses is often replaced by a high intensity light that emits brief omnidirectional flashes, concentrating the light in time rather than direction. These lights are similar to obstruction lights used to warn aircraft of tall structures. Later innovations were "Vega Lights", and experiments with light-emitting diode (LED) panels.[20]

LED lights, which use less energy and are easier to maintain, had come into widespread use by 2020. In the United Kingdom and Ireland about a third of lighthouses had been converted from filament light sources to use LEDs, and conversion continued with about three per year. The light sources are designed to replicate the colour and character of the traditional light as closely as possible. The change is often not noticed by people in the region, but sometimes a proposed change leads to calls to preserve the traditional light, including in some cases a rotating beam. A typical LED system designed to fit into the traditional 19th century Fresnel lens enclosure was developed by Trinity House and two other lighthouse authorities and costs about €20,000, depending on configuration, according to a supplier; it has large fins to dissipate heat. Lifetime of the LED light source is 50,000 to 100,000 hours, compared to about 1,000 hours for a filament source.[28]

Laser light

Experimental installations of laser lights, either at high power to provide a "line of light" in the sky or, utilising low power, aimed towards mariners have identified problems of increased complexity in installation and maintenance, and high power requirements. The first practical installation, in 1971 at Point Danger lighthouse, Queensland, was replaced by a conventional light after four years because the beam was too narrow to be seen easily.[29][30]

Light characteristics

In any of these designs an observer, rather than seeing a continuous weak light, sees a brighter light during short time intervals. These instants of bright light are arranged to create a light characteristic or pattern specific to a lighthouse.[31] For example, the Scheveningen Lighthouse flashes are alternately 2.5 and 7.5 seconds. Some lights have sectors of a particular color (usually formed by colored panes in the lantern) to distinguish safe water areas from dangerous shoals. Modern lighthouses often have unique reflectors or Racon transponders so the radar signature of the light is also unique.

Lens

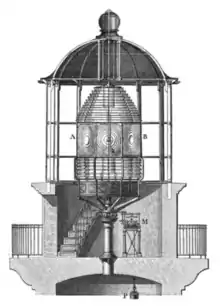

Before modern strobe lights, lenses were used to concentrate the light from a continuous source. Vertical light rays of the lamp are redirected into a horizontal plane, and horizontally the light is focused into one or a few directions at a time, with the light beam swept around. As a result, in addition to seeing the side of the light beam, the light is directly visible from greater distances, and with an identifying light characteristic.

This concentration of light is accomplished with a rotating lens assembly. In early lighthouses, the light source was a kerosene lamp or, earlier, an animal or vegetable oil Argand lamp, and the lenses rotated by a weight driven clockwork assembly wound by lighthouse keepers, sometimes as often as every two hours. The lens assembly sometimes floated in liquid mercury to reduce friction. In more modern lighthouses, electric lights and motor drives were used, generally powered by diesel electric generators. These also supplied electricity for the lighthouse keepers.[20]

Efficiently concentrating the light from a large omnidirectional light source requires a very large diameter lens. This would require a very thick and heavy lens if a conventional lens were used. The Fresnel lens (pronounced /freɪˈnɛl/) focused 85% of a lamp's light versus the 20% focused with the parabolic reflectors of the time. Its design enabled construction of lenses of large size and short focal length without the weight and volume of material in conventional lens designs.[32]

Fresnel lighthouse lenses are ranked by order, a measure of refracting power, with a first order lens being the largest, most powerful and expensive; and a sixth order lens being the smallest. The order is based on the focal length of the lens. A first order lens has the longest focal length, with the sixth being the shortest. Coastal lighthouses generally use first, second, or third order lenses, while harbor lights and beacons use fourth, fifth, or sixth order lenses.[33]

Some lighthouses, such as those at Cape Race, Newfoundland, and Makapuu Point, Hawaii, used a more powerful hyperradiant Fresnel lens manufactured by the firm of Chance Brothers.

Building

Components

While lighthouse buildings differ depending on the location and purpose, they tend to have common components.

A light station comprises the lighthouse tower and all outbuildings, such as the keeper's living quarters, fuel house, boathouse, and fog-signaling building. The Lighthouse itself consists of a tower structure supporting the lantern room where the light operates.

The lantern room is the glassed-in housing at the top of a lighthouse tower containing the lamp and lens. Its glass storm panes are supported by metal muntins (glazing bars) running vertically or diagonally. At the top of the lantern room is a stormproof ventilator designed to remove the smoke of the lamps and the heat that builds in the glass enclosure. A lightning rod and grounding system connected to the metal cupola roof provides a safe conduit for any lightning strikes.

Immediately beneath the lantern room is usually a Watch Room or Service Room where fuel and other supplies were kept and where the keeper prepared the lanterns for the night and often stood watch. The clockworks (for rotating the lenses) were also located there. On a lighthouse tower, an open platform called the gallery is often located outside the watch room (called the Main Gallery) or Lantern Room (Lantern Gallery). This was mainly used for cleaning the outside of the windows of the Lantern Room.[34]

Lighthouses near to each other that are similar in shape are often painted in a unique pattern so they can easily be recognized during daylight, a marking known as a daymark. The black and white barber pole spiral pattern of Cape Hatteras Lighthouse is one example. Race Rocks Light in western Canada is painted in horizontal black and white bands to stand out against the horizon.

Design

For effectiveness, the lamp must be high enough to be seen before the danger is reached by a mariner. The minimum height is calculated by trigonometry (see Distance to the horizon) as , where H is the height above water in feet, and D is the distance from the lighthouse to the horizon in nautical miles, the lighthouse range.[35]

Where dangerous shoals are located far off a flat sandy beach, the prototypical tall masonry coastal lighthouse is constructed to assist the navigator making a landfall after an ocean crossing. Often these are cylindrical to reduce the effect of wind on a tall structure, such as Cape May Light. Smaller versions of this design are often used as harbor lights to mark the entrance into a harbor, such as New London Harbor Light.

Where a tall cliff exists, a smaller structure may be placed on top such as at Horton Point Light. Sometimes, such a location can be too high, for example along the west coast of the United States, where frequent low clouds can obscure the light. In these cases, lighthouses are placed below the clifftop to ensure that they can still be seen at the surface during periods of fog or low clouds, as at Point Reyes Lighthouse. Another example is in San Diego, California: the Old Point Loma lighthouse was too high up and often obscured by fog, so it was replaced in 1891 with a lower lighthouse, New Point Loma lighthouse.

As technology advanced, prefabricated skeletal iron or steel structures tended to be used for lighthouses constructed in the 20th century. These often have a narrow cylindrical core surrounded by an open lattice work bracing, such as Finns Point Range Light.

Sometimes a lighthouse needs to be constructed in the water itself. Wave-washed lighthouses are masonry structures constructed to withstand water impact, such as Eddystone Lighthouse in Britain and the St. George Reef Light of California. In shallower bays, Screw-pile lighthouse ironwork structures are screwed into the seabed and a low wooden structure is placed above the open framework, such as Thomas Point Shoal Lighthouse. As screw piles can be disrupted by ice, steel caisson lighthouses such as Orient Point Light are used in cold climates. Orient Long Beach Bar Light (Bug Light) is a blend of a screw pile light that was converted to a caisson light because of the threat of ice damage.[36] Skeletal iron towers with screw-pile foundations were built on the Florida Reef along the Florida Keys, beginning with the Carysfort Reef Light in 1852.[37]

In waters too deep for a conventional structure, a lightship might be used instead of a lighthouse, such as the former lightship Columbia. Most of these have now been replaced by fixed light platforms (such as Ambrose Light) similar to those used for offshore oil exploration.[33]

Range lights

Aligning two fixed points on land provides a navigator with a line of position called a range in North America and a transit in Britain. Ranges can be used to precisely align a vessel within a narrow channel such as a river. With landmarks of a range illuminated with a set of fixed lighthouses, nighttime navigation is possible.

Such paired lighthouses are called range lights in North America and leading lights in the United Kingdom. The closer light is referred to as the beacon or front range; the further light is called the rear range. The rear range light is almost always taller than the front.

When a vessel is on the correct course, the two lights align vertically, but when the observer is out of position, the difference in alignment indicates the direction of travel to correct the course.

Location

There are two types of lighthouses: ones that are located on land, and ones that are offshore.

Offshore Lighthouses are lighthouses that are not close to land.[38] There can be a number of reasons for these lighthouses to be built. There can be a shoal, reef or submerged island several miles from land.

The current Cordouan Lighthouse was completed in 1611, 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) from the shore on a small islet, but was built on a previous lighthouse that can be traced back to the 880s and is the oldest surviving lighthouse in France. It is connected to the mainland by a causeway. The oldest surviving oceanic offshore lighthouse is Bell Rock Lighthouse in the North Sea, off the coast of Scotland.[39]

Maintenance

Asia and Oceania

In Australia, lighthouses are conducted by the Australian Maritime Safety Authority.

In India, lighthouses are maintained by the Directorate General of Lighthouses and Lightships, an office of the Ministry of Ports, Shipping and Waterways.[40]

Europe

The former Soviet government built a number of automated lighthouses powered by radioisotope thermoelectric generators in remote locations in northern Russia. They operated for long periods without external support with great reliability.[41] However, numerous installations deteriorated, were stolen, or vandalized. Some cannot be found due to poor record-keeping.[42]

The United Kingdom and the Republic of Ireland together have three bodies: lighthouses around the coasts of England and Wales are looked after by Trinity House, those around Scotland and the Isle of Man by the Northern Lighthouse Board and those around Ireland by the Commissioners of Irish Lights.

North America

In Canada, lighthouses are managed by the Canadian Coast Guard.

In the United States, lighthouses are maintained by the United States Coast Guard, into which the United States Lighthouse Service was merged in 1939.[33]

Preservation

As lighthouses became less essential to navigation, many of their historic structures faced demolition or neglect. In the United States, the National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000 provides for the transfer of lighthouse structures to local governments and private non-profit groups, while the USCG continues to maintain the lamps and lenses. In Canada, the Nova Scotia Lighthouse Preservation Society won heritage status for Sambro Island Lighthouse, and sponsored the Heritage Lighthouse Protection Act to change Canadian federal laws to protect lighthouses.[43]

Many groups formed to restore and save lighthouses around the world, including the World Lighthouse Society and the United States Lighthouse Society,[44] as well as the Amateur Radio Lighthouse Society, which sends amateur radio operators to publicize the preservation of remote lighthouses throughout the world.[45]

See also

References

- Notes

- ↑ Trethewey, K. R.:Ancient Lighthouses, Jazz-Fusion Books (2018), 326pp. ISBN 978-0-99265-736-9

- ↑ Smiles, Samuel (1861), The Lives of the Engineers, vol. 2, p. 16

- ↑ "lighthouse". Retrieved 17 December 2012.

- ↑ Majdalany, Fred: The Eddystone Light. 1960

- ↑ "Eddystone – Gallery". Trinity House. Archived from the original on 9 September 2006. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ↑ Douglass, James Nicholas (1878). "Note on the Eddystone Lighthouse". Minutes of proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers. Vol. 53, part 3. London: Institution of Civil Engineers. pp. 247–248.

- 1 2 "NLB – Robert Stevenson". Retrieved 28 January 2013.

- ↑ Boucher, Cyril Thomas Goodman (1963), John Rennie, 1761–1821: The Life and Work of a Great Engineer, p. 61

- 1 2 Tomlinson, ed. (1852–1854). Tomlinson's Cyclopaedia of Useful Arts. London: Virtue & Co. p. 177.

[Maplin Sands] was not, however, the first screw-pile lighthouse actually erected, for during the long preparation process which was carried on at Maplin Sands, a structure of the same principle had been begun and completed at Port Fleetwood...

- ↑ "Lamp Glass Replacement Glass Lamp Shades, Oil Lamp Shades, Oil Lamp Chimneys, Oil Lamp Spares". Archived from the original on 6 January 2014.

- ↑ "Lamp." Encyclopædia Britannica: or, a dictionary of Arts, Science, and Miscellaneous Literature. 6th ed. 1823 Web. 5 December 2011

- ↑ "Modern Lighthouses". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 4 August 2021.

- ↑ Baird, Spencer Fullerton (1876). Annual record of science and industry. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 460.

- ↑ "John Richardson Wigham 1829–1906" (PDF). BEAM. Commissioners of Irish Lights. 35: 21–22. 2006–2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 March 2012.

- ↑ "The Linde Group - Gases Engineering Healthcare -". Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ↑ "Lighthouse". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- ↑ Watson, Bruce. "Science Makes a Better Lighthouse Lens." Smithsonian. August 1999 v30 i5 p30. produced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Thomson Gale. 2005.

- ↑ "Maritime Heritage Program - National Park Service". Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ↑ "Lighthouses of British Columbia". Archived from the original on 3 November 2011. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Crompton & Rhein (2002)

- ↑ Nicholson, Christopher (2000). Rock lighthouses of Britain : the end of an era?. Caithness, Scotland: Whittles. p. 126. ISBN 978-1870325417.

- ↑ "Obituary - Richard Henry Brunton". Minutes of the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers. Vol. 145, no. 1901. 1901. pp. 340–341. doi:10.1680/imotp.1901.18577. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ↑

Beare, Thomas Hudson (1901). "Douglass, James Nicholas". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

Beare, Thomas Hudson (1901). "Douglass, James Nicholas". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co. - ↑ "Maritime Heritage Program - National Park Service". Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ↑ Guigueno, Vincent (January 2006). "Review of Thobie, Jacques, L'administration generale des phares de l'Empire ottoman et la societe Collas et Michel, 1860–1960. H-Mediterranean, H-Net Reviews. January, 2006". Humanities and Social Sciences Net Online. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

- ↑ "Nuclear lighthouses to be replaced - Bellona". June 23, 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-06-23.

- ↑ "Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators - Bellona". March 15, 2011. Archived from the original on 2011-03-15.

- 1 2 Baraniuk, Chris (15 September 2020). "When changing a light bulb is a really big deal". BBC News. Archived from the original on Jun 19, 2023.

- ↑ "Point Danger Lighthouse". Lighthouses of Australia Inc. 26 January 2018. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- ↑ "Lasers". Aids to Navigation Manual. St Germain en Laye, France: International Association of Marine Aids to Navigation and Lighthouse Authorities: 43. March 2010.

- ↑ "Aids To Navigation Abbreviations". Archived from the original on September 25, 2008.

- ↑ "Lighthouses: An Administrative History". Maritime Heritage Program – Lighthouse Heritage. U.S. National Park Service. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- 1 2 3 "Maritime Heritage Program | National Park Service". www.nps.gov.

- ↑ "Light Station Components". nps.gov.

- ↑ "How to Calculate the Distance to the Horizon".

- ↑ "Maritime Heritage Program - National Park Service". Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ↑ Dean, Love (1982). Reef Lights. Key West, Florida: The Historic Key West Preservation Board. ISBN 0-943528-03-8.

- ↑ "Lighthouse Terminology Part 2", Sea Girt Lighthouse, archived from the original on 4 April 2013, retrieved 15 February 2013,

A lighthouse located offshore, built on a foundation of pilings, rocks or caissons.

- ↑ Cadbury, Deborah (2012), Seven Wonders of the Industrial World (Text only ed.), HarperCollins UK, p. 106, ISBN 978-0007388929.

- ↑ R.K. Bhanti. "Indian Lighthouses - An Overview" (PDF). Directorate General of Lighthouses and Lightships. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- ↑ "RTG Heat Sources: Two Proven Materials - Atomic Insights". 1 September 1996. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- ↑ "Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators – Bellona". Archived from the original on June 13, 2006.

- ↑ Douglas Franklin. "Lighthouse Bill Protecting Our Lighthouses – The Icons of Canada's Maritime Heritage". Featured Heritage Buildings. Canadian Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008. Retrieved 10 June 2008.

- ↑ "Home | United States Lighthouse Society". uslhs.org.

- ↑ "Amateur Radio Lighthouse Society – Contacting the Light Beacons of the World". Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- Bibliography

- Bathurst, Bella. The lighthouse Stevensons. New York: Perennial, 2000. ISBN 0-06-093226-0

- Beaver, Patrick. A History of Lighthouses. London: Peter Davies Ltd, 1971. ISBN 0-432-01290-7.

- Crompton, Samuel, W; Rhein, Michael, J. The Ultimate Book of Lighthouses. San Diego, CA: Thunder Bay Press, 2002. ISBN 1-59223-102-0.

- Jones, Ray; Roberts, Bruce. American Lighthouses. Globe Pequot, 1998. 1st ed. ISBN 0-7627-0324-5.

- Stevenson, D. Alan. The world's lighthouses before 1820. London: Oxford University Press, 1959.

- Further reading

- Noble, Dennis. Lighthouses & Keepers: U. S. Lighthouse Service and Its Legacy. Annapolis: U.S. Naval Institute Press, 1997. ISBN 1-55750-638-8.

- Putnam, George R. Lighthouses and Lightships of the United States. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1933.

- Rawlings, William. 2021. Lighthouses of the Georgia Coast. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press.

- Weiss, George. The Lighthouse Service, Its History, Activities and Organization. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1926.

External links

- United States Lighthouses

- "Lighthouses Of Strange Designs, December 1930, Popular Science

- Rowlett, Russ. "The Lighthouse Directory". University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Research tool with details of over 14,700 lighthouses and navigation lights around the world with photos and links.

- Pharology Website: Pharology: The Study of Lighthouses . Reference source for the history and development of lighthouses of the world.

- Douglass, W. T.; Gedye, N. G. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). pp. 627–651. Includes 54 diagrams and photographs.

_-_cropped.jpg.webp)