Sir Cloudesley Shovell | |

|---|---|

Sir Cloudesley Shovell by Michael Dahl | |

| Born | November 1650 Cockthorpe, Norfolk |

| Died | 22 October or 23 October 1707 Off the coast of Scilly |

| Buried | St Mary's, Isles of Scilly, later moved to Westminster Abbey |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1664–1707 |

| Rank | Admiral of the Fleet |

| Commands held | HMS Sapphire HMS Phoenix HMS Nonsuch HMS James Galley HMS Anne HMS Dover HMS Edgar HMS Monck Irish Squadron Lisbon Station Mediterranean Fleet |

| Battles/wars | |

| Other work | MP for the city of Rochester |

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Cloudesley Shovell (c. November 1650 – 22 or 23 October 1707) was an English naval officer. As a junior officer he saw action at the Battle of Solebay and then at the Battle of Texel during the Third Anglo-Dutch War. As a captain he fought at the Battle of Bantry Bay during the Williamite War in Ireland.

As a flag officer Shovell commanded a division at the Battle of Barfleur during the Nine Years' War, and during the battle distinguished himself by being the first to break through the enemy's line. Along with Admiral Henry Killigrew and Admiral Ralph Delaval, Shovell was put in joint command of the fleet shortly afterwards.

During the War of the Spanish Succession, Shovell commanded a squadron which served under Admiral George Rooke at the capture of Gibraltar and the Battle of Málaga. Working in conjunction with a landing force under the Earl of Peterborough, his forces undertook the siege and capture of Barcelona. He was appointed commander-in-chief of the Navy while at Lisbon the following year. He also commanded the naval element of a combined attack on Toulon, base of the main French fleet, in coordination with the Austrian army under Prince Eugene of Savoy in the summer of 1707. Later that year, on the return voyage to England, Shovell and more than 1,400 others perished in a disastrous shipwreck off the Isles of Scilly.

Along with his naval service, Shovell served as MP for Rochester from 1695 to 1701 and from 1705 until his death in 1707.

Early career

Born in Cockthorpe,[1] the son of John Shovell, a Norfolk gentleman, and Anne Shovell (née Jenkinson), Shovell was born into a family "of property and distinction"[2] which, although not poor, was by no means wealthy.[3] He was baptised on 25 November 1650.[4] The unusual first name of Cloudesley derives from the surname of his maternal grandmother Lucy Cloudisley, who was the daughter of Thomas Cloudisley.[5]

He went to sea as a cabin boy in the care of a paternal relative, Admiral Sir Christopher Myngs, in 1663. After Myngs' death in 1666 he remained at sea in the care of Admiral Sir John Narborough.[5] He set himself to study navigation, and, owing to his able seamanship and brave disposition, became a general favourite and obtained quick promotion.[4] Promoted to midshipman on 22 January 1672, he was assigned to the first-rate HMS Royal Prince, flagship of the Duke of York, and saw action when a combined British and French fleet was surprised and attacked by the Dutch, led by Admiral Michiel de Ruyter, at the Battle of Solebay off the Suffolk coast in May 1672, during the Third Anglo-Dutch War.[5]

Promoted to master's mate on 17 September 1672, Shovell transferred to the third-rate HMS Fairfax later that month and then moved to the third-rate HMS Henrietta in November 1672. He saw action again when a combined British and French fleet attempting to land troops in the Netherlands was repelled by a smaller Dutch force, again led by Admiral de Ruyter, at the Battle of Texel in August 1673.[3] Promoted to lieutenant on 25 September 1673, he transferred to the third-rate HMS Harwich in 1675 and took part in an action against the pirate stronghold at Tripoli. Shovell led a surprise attack on the pirates, sinking a number of their ships in January 1676. For this action he received the sum of £80 from Narborough. Two months later he undertook a second raid against the pirates, for which he was awarded a gold medal from King Charles II. In a letter from the Admiralty, Samuel Pepys recorded the King's satisfaction with Shovell's actions; he transferred to the third-rate HMS Plymouth in May 1677 and was sent to the Mediterranean.[3]

.png.webp)

Promoted to captain 17 September 1677, Shovell was given command of the fifth-rate HMS Sapphire. He transferred to the fourth-rate HMS Phoenix in April 1679 and returned to HMS Sapphire in May 1679 before transferring to the fifth-rate HMS Nonsuch in July 1680. He returned to HMS Sapphire again in September 1680 and then transferred to the sixth-rate HMS James Galley in April 1681, to the third-rate HMS Anne in April 1687 and to the fourth-rate HMS Dover in April 1688. Throughout this period Shovell was engaged in the defence of Tangier from Salé raiders.[3]

Shovell transferred to the command of the third-rate HMS Edgar in April 1689 and saw action at the Battle of Bantry Bay in May 1689, when a French fleet tried to land troops in Southern Ireland to fight Prince William of Orange during the Williamite War in Ireland. After the battle, Commodore John Ashby and Shovell were knighted. He transferred to the third-rate HMS Monck in October 1689 and ordered to patrol the area between Ireland and the Isles of Scilly. In June 1690 he was commodore of a small squadron, which convoyed King William across St George's Channel to Carrickfergus.[3]

Senior command

Promoted to rear-admiral on 3 June 1690, Shovell hoisted his flag in the first-rate HMS Royal William. He provided naval support for Percy Kirke's Capture of Waterford in July 1690 commanding the Irish Squadron. He commanded a division of the Red squadron at the Battles of Barfleur and La Hogue in May 1692, in which Russell's Anglo-Dutch fleet intercepted and defeated the French fleet under Tourville, on its way along the Channel to provide an escort for an invasion of England. At Barfleur Shovell's flagship was the first ship to break through the enemy's line, and in the latter stages of the battle he organised a fireship attack. He received a wound in the thigh during the action, which later incapacitated him during preparations for the attack which destroyed the French ships that had taken refuge at La Hogue. Along with Admirals Henry Killigrew and Ralph Delaval, Shovell was put in joint command of the fleet in January 1693. After the disastrous attack on the Smyrna convoy off Lagos, Portugal, in June 1693, all three admirals were dismissed from their joint command. Promoted to vice admiral on 16 April 1694, Shovell commanded a squadron on expeditions to Dieppe and Dunkirk, later in the year.[3]

Shovell set up residence with his wife at May Place in Crayford in 1694 and was elected Member of Parliament for Rochester in 1695.[6] He was responsible for the restoration of St. Paulinus' Church in Crayford and was a great benefactor to Rochester, providing at his own expense the fine decorated plaster ceilings in the Guildhall and the market bell, clock and decorated brick facade for the Butchers' Market (now the Corn Exchange).[7][8] He was also Commissioner of the Sewers, responsible for the upkeep of the embankments of the Thames between Deptford and Gravesend.[7] He did not stand for re-election to Parliament in December 1701.[6]

War of the Spanish Succession

Promoted to full admiral on 6 May 1702, Shovell brought home the spoils of the French and Spanish fleets, which had been captured by Admiral George Rooke at the Battle of Vigo at an early stage of the War of the Spanish Succession,[4] arriving in England in late 1702. After commanding a fleet dispatched to take troops to Lisbon in Spring 1703, he commanded a squadron which served under Rooke at the capture of Gibraltar in August 1704 and also repulsed the French fleet at the Battle of Málaga later that month. He was appointed a member of the council of the Lord High Admiral (an office vested at that time in Prince George of Denmark) in December 1704, appointed Rear-Admiral of England on 26 December 1704 and promoted to Admiral of the Fleet on 13 January 1705.[3][6]

He was elected Member of Parliament for Rochester again in 1705.[6] In May 1705 he was given command of the Mediterranean Fleet in partnership with Earl of Peterborough. Peterborough's forces undertook the siege and capture of Barcelona in September 1705. Shovell was given complete control of the Mediterranean Fleet while at Lisbon in November 1706.[3] He commanded the naval element of a combined attack on Toulon, base of the main French fleet, in coordination with the Austrian army under Prince Eugene of Savoy in the summer of 1707. The allies failed to capture the city, but bombardment by Shovell's forces panicked the French into scuttling their own fleet. Shovell was subsequently ordered to bring his fleet home in late October 1707.[3]

Death in the Scilly naval disaster

.jpg.webp)

While returning with the fleet to England after the campaign at Toulon, Shovell's flagship, the second-rate HMS Association, struck the rocks near the Isles of Scilly at 8 pm on 22 October (2 November, by the modern calendar) 1707. HMS Association went down in three or four minutes, with none of the 800 men that were on board saved,[4] according to sailors watching on the first-rate HMS St George. Four large ships, HMS Association, the third-rate HMS Eagle, the fourth-rate HMS Romney and the fire ship HMS Firebrand all sank.[9]

With nearly 2,000 sailors lost that night, the Scilly naval disaster was recorded as one of the greatest maritime disasters in British history.[9] The cause of the disaster has often been represented as the navigators' inability to accurately calculate their longitude, although no public discussion of the events specifically raising the question of longitude is known, prior to a pamphlet published on the eve of Parliament's vote on the Longitude Act, seven years later.[10][11]

Shovell's body and those of both his stepsons were all found in Porthellick Cove on St Mary's, almost 7 miles (11 km) from where his ship was wrecked. It was possible that Shovell left his flagship in one of its boats along with his two stepsons and the captain of HMS Association, Edmund Loades, and that they were drowned while trying to get to shore.[3]

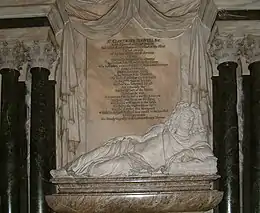

Shovell's body was identified by the purser of the third-rate HMS Arundel, who knew the admiral well. It was identified by "a black mole under his left ear, also by the first joint of one of his forefingers being broken inwards. He had likewise a shot in his right arm, another in his left thigh".[12] Shovell was temporarily buried on the beach at Porthellick Cove.[13] By order of Queen Anne the body was later exhumed and brought back in the fourth-rate HMS Salisbury to Plymouth, where it was embalmed by Dr James Yonge. It was later carried in state to London. During the journey from the West Country, large crowds turned out to pay their respects. He was interred in Westminster Abbey on 22 December 1707: his large marble monument in the south choir aisle was sculpted by Grinling Gibbons.[14] Meanwhile, his two stepsons were buried in Old Town Church on St Mary's.[3]

Local legend has it that Shovell was alive, at least barely, when he reached the shore of Scilly at Porthellick Cove but was murdered by a woman for the sake of his priceless emerald ring, which had been given to him by a close friend, Captain James Lord Dursley. At that time, the Scillies had a wild and lawless reputation. It is claimed that the murder came to light only some thirty years later when the woman, on her deathbed, confessed to a clergyman to having killed the admiral and produced the stolen ring, which was sent back to Dursley.[3][10] Several historians doubt the murder story as there is no indication that the ring was recovered and the legend stems from a romantic and unverifiable deathbed confession.[15][16]

Another legend alleges that a common sailor on the flagship tried to warn Shovell that the fleet was off course but Shovell had him hanged at the yardarm for inciting mutiny. The story first appeared in the Scilly Isles in 1780, with the common sailor being a Scilly native, who recognized the waters as being close to home but was punished for warning the admiral.[12] While it is possible that a sailor may have debated the vessel's location and feared for its fate (such debates were common upon entering the English Channel, as noted by Samuel Pepys in 1684), the story has been repeatedly discredited by naval scholars, who noted the lack of any evidence in contemporary documents and its fanciful stock conventions and dubious origins.[12] After his death Shovell became a popular British hero.[17]

Family

In 1691 Shovell married Elizabeth Hill, Lady Narborough (1661–1732), the widow of his former commander, Rear Admiral Sir John Narborough. Through her, he had two stepsons (Sir John Narborough, 1st Baronet, and James Narborough), who both entered naval careers and died, aged 23 and 22, at the sinking of HMS Association in October 1707.[12] Shovell and his wife also had two daughters: Elizabeth and Anne. Elizabeth married Lord Romney, whilst Anne married John Blackwood.[7]

In popular media

Actor Jonathan Coy was cast as Shovell in the Channel 4 TV series, Longitude in 2000.[18]

References

- ↑ "Sir Cloudesley Shovell - Lord of the Manor of Crayford". Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- ↑ Le Fevre and Harding, p. 44

- 1 2 3 4 Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 24 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 1014.

- 1 2 3 "Cloudesley Shovell". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/25470. Retrieved 24 May 2015. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 3 4 "Shovell, Sir Clowdesley (1650-1707), of Soho Square, London and May Place, Crayford, Kent". History of Parliament. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 Thomas, E.O., Slade Green and the Crayford Marshes, Bexley Education and Leisure Services Directorate, 2001, ISBN 0-902541-55-2

- ↑ "Guilfhall Museum". Medway Council. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- 1 2 Sobel, p. 6

- 1 2 Sobel, p. 11–16

- ↑ Dunn, Richard (27 October 2014). "The 1707 Isles of Scilly Disaster – Part 2". Board of Longitude Project, Royal Museums Greenwich. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Cooke, James (1883). "Shipwreck of Sir Cloudesley Shovel". Society of Antiquaries. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ↑ "Sir Clowdisley Shovell and The Association". Submerged. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ↑ "Sir Clowdisley Shovell's tomb and memorial in Westminster Abbey". Westminster Abbey. Archived from the original on 16 October 2009. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- ↑ Powell, p. 333–336

- ↑ Pickwell, p. 221–223

- ↑ Nicholls, p. 25-30

- ↑ "Longitude (1999)". movie-dude.com. Retrieved 22 June 2021.

Sources

- Le Fevre, Peter; Harding, Richard (2000). Precursors of Nelson: British admirals of the eighteenth century. London: Chatham. ISBN 978-0-81172-901-7.

- Nicholls, Mark (2008). Norfolk Maritime Heroes and Legends. Cromer: Poppyland Publishing. ISBN 978-0-946148-85-1.

- Pickwell, J G (1973). "Improbable Legends surrounding the Shipwreck of Sir Clowdisley Shovell". The Mariner's Mirror. London: Society for Nautical Research. 59 (2): 221–223. doi:10.1080/00253359.1973.10657899. ISSN 0025-3359.

- Powell, Damer (1957). "The Wreck of Sir Cloudesley Shovell". The Mariner's Mirror. Glasgow: Society for Nautical Research. 43. ISSN 0025-3359.

- Sobel, Dava (1998). Longitude: The True Story of a Lone Genius Who Solved the Greatest Scientific Problem of His Time. London: Fourth Estate. ISBN 1-85702-571-7.

Further reading

- Campbell, John (1744). "Memoirs of Sir Cloudesley Shovel, Knt. Rear-Admiral of England, Etc.". Lives of the Admirals. London: J. and H. Pemberton and T. Waller. OCLC 28075391. Archived from the original on 19 October 2009.

- Harris, Simon (2000). Sir Cloudesley Shovell: Stuart Admiral. Staplehurst: Spellmount. ISBN 1-86227-099-6.

- McBride, Peter; Larn, Richard (1999). Admiral Shovell's Treasure and Shipwreck in the Isles of Scilly. Shipwreck & Marine. ISBN 0-9523971-3-7.

- The Life and Glorious Actions of Sir C. Shovel, Admiral of the Confederate Fleet in the Mediterranean Sea, etc. D. Brown. 1707.

External links

- "A Biographical Memoir of Sir Cloudesly Shovel" – Originally printed in the March 1815 issue of The Naval Chronicle

- Cloudesley Shovell Three Decks