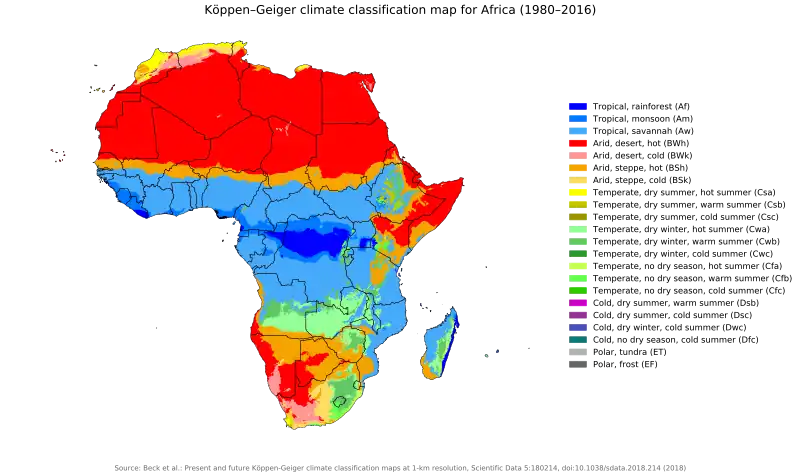

The climate of Africa is a range of climates such as the equatorial climate, the tropical wet and dry climate, the tropical monsoon climate, the semi-arid climate (semi-desert and steppe), the desert climate (hyper-arid and arid), the humid subtropical climate, and the subtropical highland climate. Temperate climates are rare across the continent except at very high elevations and along the fringes. In fact, the climate of Africa is more variable by rainfall amount than by temperatures, which are consistently high. African deserts are the sunniest and the driest parts of the continent, owing to the prevailing presence of the subtropical ridge with subsiding, hot, dry air masses. Africa holds many heat-related records: the continent has the hottest extended region year-round, the areas with the hottest summer climate, the highest sunshine duration, and more.

Owing to Africa's position across equatorial and subtropical latitudes in both the northern and southern hemisphere, several different climate types can be found within it. The continent mainly lies within the intertropical zone between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn, hence its interesting density of humidity. Precipitation intensity is always high, and it is a hot continent. Warm and hot climates prevail all over Africa, but mostly the northern part is marked by aridity and high temperatures. Only the northernmost and the southernmost fringes of the continent have a Mediterranean climate. The equator runs through the middle of Africa, as do the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn, making Africa the most tropical continent.

Temperatures

Globally, heating of the earth near the equator leads to large amounts of upward motion and convection along the monsoon trough or Intertropical Convergence Zone. The divergence over the near-equatorial trough leads to air rising and moving away from the equator aloft. As it moves towards the Mid-Latitudes, the air cools and sinks, which leads to subsidence near the 30th parallel of both hemispheres. This circulation is known as the Hadley cell and leads to the formation of the subtropical ridge.[2] Many of the world's deserts are caused by these climatological high-pressure areas,[3] including the Sahara Desert.

Temperatures are hottest within the Sahara regions of Algeria and Mali,[4] and coolest across the south and at elevation within the topography across the eastern and northwest sections of the continent. The hottest average temperature on Earth is at Dallol, Ethiopia, which averages a temperature of 33.9 °C (93.0 °F) throughout the year.[5] The hottest temperature recorded within Africa, which was also the world record, was 57.8 °C (136.0 °F) at 'Aziziya, Libya, on 13 September 1922. This was later proven to be false, being derived from an inaccurate reading of a thermometer. The world's hottest place is in fact Death Valley, in California.[6][7][8] Apparent temperatures, combining the effect of the temperature and humidity, along the Red Sea coast of Eritrea and Gulf of Aden coast of Somalia range between 57 °C (135 °F) and 63 °C (145 °F) during the afternoon hours.[4] The lowest temperature measured within Africa was −24 °C (−11 °F) at Ifrane, Morocco, on 11 February 1935.[9] Nevertheless, the major part of Africa experiences extreme heat during much of the year, especially the deserts, semi-deserts, steppes and savannas. The African deserts are arguably the hottest places on Earth, especially the Sahara Desert and the Danakil Desert, located in the Horn of Africa.

Wind

The mid-level African easterly jet stream north of the equator is considered to play a crucial role in the West African monsoon,[10] and helps form the tropical waves which march across the tropical Atlantic and the eastern part of the Pacific during the warm season.[11] The jet exhibits both barotropic and baroclinic instability, which produces synoptic-scale, westward-propagating disturbances in the jet known as African easterly waves, or tropical waves. A small number of mesoscale storm systems embedded in these waves develop into tropical cyclones after they move from west Africa into the tropical Atlantic, mainly during August and September. When the jet lies south of normal during the peak months of the Atlantic hurricane season, tropical cyclone formation is suppressed.[12]

Low-level jets are fast winds which form close to the surface (within 1.5 km). They affect a number of climate processes across Africa. The Somali Low-level Jet,[13] which forms of the coast of East Africa, contributes to the existence of the Somali Desert.[14][15] Low-level jets of the Sahara are known to be important for raising dust off the dry desert surface. For example, the low-level jet over Chad,[16] is the driver of dust emission from the Bodélé Depression, the largest source of atmospheric dust on the planet.[17] Easterly low-level jets which form in river valleys across the East African Rift System supply millions of tonnes of water vapour originating from the Indian Ocean across East Africa and to the Congo rainforest.[18] In doing so, they leave East Africa unusually dry for its latitude.[19] Low-level southwesterlies emanating from the Gulf of Guinea are the key moisture source for the West African monsoon in northern hemisphere summer.[20]

The Tropical Easterly Jet, which forms high up in the atmosphere, 15-17 km above the surface, is another important factor. Variations to the speed and position of this jet stream can affect rainfall in the Congo Basin and the Sahel.[21]

Precipitation

Great parts of North Africa and Southern Africa as well as the whole Horn of Africa mainly have a hot desert climate, or a hot semi-arid climate for the wetter locations. The Sahara Desert in North Africa is the largest hot desert in the world and is one of the hottest, driest and sunniest places on Earth. Located just south of the Sahara is a narrow semi-desert steppe (a semi-arid region) called the Sahel, while Africa's most southern areas contain both savanna plains, and its central portion, including the Congo Basin, contains very dense jungle (rainforest) regions. The western equatorial region is the wettest portion of the continent. Annually, the rain belt across the continent moves northward into Sub-Saharan Africa by August, then passes back southward into south-central Africa by March.[22] Areas with a savannah climate in Sub-Saharan Africa, such as Ghana, Burkina Faso,[23][24] Darfur,[25] Eritrea,[26] Ethiopia,[27] and Botswana have a distinct rainy season.[28] El Nino results in drier-than-normal conditions in Southern Africa from December to February, and wetter-than-normal conditions in equatorial East Africa over the same period.[29]

In Madagascar, trade winds bring moisture up the eastern slopes of the island, which is deposited as rainfall, and bring drier downsloped winds to areas south and west, leaving the western sections of the island in a rain shadow. This leads to significantly more rainfall over northeast sections of Madagascar than its southwestern portions.[30] Southern Africa receives most of its rainfall from summer convective storms, tropical lows, mesoscale convective systems. Extratropical cyclones moving through the Westerlies, can also bring significant rainfall. Once a decade, tropical cyclones lead to excessive rainfall across the region.[31]

Snow and glaciers

Snow is an almost annual occurrence on some of the mountains of South Africa, including those of the Cedarberg and around Ceres in the South-Western Cape, and on the Drakensberg in Natal and Lesotho. Tiffendell Resort, in the Drakensberg, is the only commercial ski resort in South Africa, and has "advanced snow-making capability" allowing skiing for three months of the year.[32] The Mountain Club of South Africa (MCSA) and the Mountain and Ski Club (MSC)[33] of the University of Cape Town both have equipped ski huts in the Hex River mountains. Skiing including snowboarding in the Cape is a hit-and-miss affair, both in terms of timing of snowfalls, and whether there is sufficient snow to cover the rocks.

Table Mountain gets a light dusting of snow on the Front Table and also at Devil's Peak every few years. Snowfalls on Table Mountain took place on 20 September 2013;[34] 30 August 2013;[35] 5 August 2011;[36] and on 15 June 2010.[37]

Snow is a rare occurrence in Johannesburg; it fell in May 1956, August 1962, June 1964, September 1981, August 2006, and on 27 June 2007,[38] accumulating up to 10 centimetres (3.9 in) in the southern suburbs.

Additionally, snow regularly falls in the Atlas Mountains in the Maghreb, as well as the Mediterranean regions and Sinai peninsula of Egypt. Snowfall is also a regular occurrence at Mount Kenya and Mount Kilimanjaro in Tanzania.

There have been permanent glaciers on the Rwenzori Mountains, on the border of Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. However, by the 2010s, the glaciers were in retreat, and they are under threat of disappearing through rising temperatures.[39]

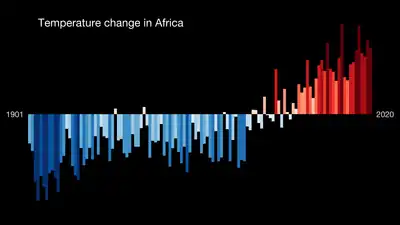

Climate change

Climate change in Africa is an increasingly serious threat as Africa is among the most vulnerable continents to the effects of climate change.[40][41][42] Some sources even classify Africa as "the most vulnerable continent on Earth".[43][44] This vulnerability is driven by a range of factors that include weak adaptive capacity, high dependence on ecosystem goods for livelihoods, and less developed agricultural production systems.[45] The risks of climate change on agricultural production, food security, water resources and ecosystem services will likely have increasingly severe consequences on lives and sustainable development prospects in Africa.[41] With high confidence, it was projected by the IPCC in 2007 that in many African countries and regions, agricultural production and food security would probably be severely compromised by climate change and climate variability.[46] Managing this risk requires an integration of mitigation and adaptation strategies in the management of ecosystem goods and services, and the agriculture production systems in Africa.[47]

Over the coming decades, warming from climate change is expected across almost all the Earth's surface, and global mean rainfall will increase.[48] Currently, Africa is warming faster than the rest of the world on average. Large portions of the continent may become uninhabitable as a result of the rapid effects of climate change, which would have disastrous effects on human health, food security, and poverty.[49][50][51] Regional effects on rainfall in the tropics are expected to be much more spatially variable and the sign of change at any one location is often less certain, although changes are expected. Consistent with this, observed surface temperatures have generally increased over Africa since the late 19th century to the early 21st century by about 1 °C, but locally as much as 3 °C for minimum temperature in the Sahel at the end of the dry season.[52] Observed precipitation trends indicate spatial and temporal discrepancies as expected.[53][41] The observed changes in temperature and precipitation vary regionally.[54][53]

For instance, Kenya experiences high vulnerability to the impacts of climate change. The main climate hazards include droughts and floods with current projects forecasting more intense and less predictable rainfall. In addition, other projections anticipate temperatures rising by 0.5 to 2 °C.[55] In crowded, urban settlements in Nairobi, Kenya, the conditions of informal settlements or "slums" may exacerbate the impacts of climate change and disaster-related risk.[56] In particular, the living conditions of large informal settlements often create a warmer "micro-climate" due to home construction materials, lack of ventilation, sparse green space, and poor access to electrical power and other services.[57] To mitigate climate change-related risks in these informal neighborhood settlements, it will be important to upgrade these settlements through urban development interventions that are built for climate resilience.

In terms of adaptation efforts, regional-level actors are making some progress. This includes the development and adoption of several regional climate change adaptation strategies[58] e.g. SADC Policy Paper Climate Change,[59] and the adaptation strategy for the water sector.[60] In addition, there have been other efforts to enhance climate change adaptation, such as the Programme on Climate Change Adaptation, Mitigation in Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA-EAC-SADC).[61]

As a supranational organisation of 55 member states, the African Union has put forward 47 goals and corresponding actions in a 2014 draft report[62] to combat and mitigate climate change on the continent. The Secretary General of the United Nations has also declared a need for close cooperation with the African Union to tackle climate change, in accordance with the UN's sustainable development goals. The United Nations estimates that, considering the continent's population growth, yearly funding of $1.3 trillion would be needed to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals in Africa. The International Monetary Fund also estimates that $50 billion may be needed only to cover the expenses of climate adaptation.[63][64][65]In chapter 9 of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, it is reported that although greenhouse gas emissions are among the lowest in Africa, anthropogenic climate change has severely threatened daily life. People experience extreme food insecurity, high mortality rates, major biodiversity loss, and more as a result of global warming. Additionally, because of reduced economic activity and growth and inequities in funding, the ability for adaptation to these conditions is also reduced.[66]

See also

References

- ↑ Beck, Hylke E.; Zimmermann, Niklaus E.; McVicar, Tim R.; Vergopolan, Noemi; Berg, Alexis; Wood, Eric F. (30 October 2018). "Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps at 1-km resolution". Scientific Data. 5: 180214. Bibcode:2018NatSD...580214B. doi:10.1038/sdata.2018.214. ISSN 2052-4463. PMC 6207062. PMID 30375988.

- ↑ Thompson, Owen E. (1996). "Hadley Circulation Cell". Archived 5 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine Channel Video Productions. Retrieved 11 February 2007.

- ↑ ThinkQuest team 26634 (1999). "The Formation of Deserts". Archived 17 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Oracle ThinkQuest Education Foundation. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- 1 2 Burt, Christopher C. (2004). Extreme Weather: a guide & record book. W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. pp. 24–28. ISBN 978-0-393-32658-1.

- ↑ Wagner, Ronald L.; Bill Adler, Jr. (1997). The Weather Sourcebook. Adler & Robin Books, Inc. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-76270-080-6.

- ↑ "NCDC: Global Measured Extremes of Temperature and Precipitation". Archived from the original on 22 June 2007.

- ↑ El Fadli, K. I.; et al. (September 2012). "World Meteorological Organization Assessment of the Purported World Record 58°C Temperature Extreme at El Azizia, Libya (13 September 1922)". Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society. 94 (2): 199–204. Bibcode:2013BAMS...94..199E. doi:10.1175/BAMS-D-12-00093.1. (The 136 °F (57.8 °C), claimed by 'Aziziya, Libya, on 13 September 1922, has been officially deemed invalid by the World Meteorological Organization.)

- ↑ "World Meteorological Organization World Weather / Climate Extremes Archive". Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- ↑ "Global Measured Extremes of Temperature and Precipitation". National Climatic Data Center. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- ↑ Cook, Kerry H. "Generation of the African Easterly Jet and Its Role in Determining West African Precipitation". Retrieved 8 May 2008.

- ↑ Landsea, Chris. AOML Frequently Asked Questions. "Subject: A4) What is an easterly wave?" Retrieved 8 May 2008.

- ↑ Climate Prediction Center (November 1997). "Figure 7". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- ↑ Findlater, J. (1969), A major low-level air current near the Indian Ocean during the northern summer. Q.J.R. Meteorol. Soc., 95: 362-380. https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.49709540409

- ↑ Yang, W., R. Seager, M. A. Cane, and B. Lyon, 2015: The Annual Cycle of East African Precipitation. J. Climate, 28, 2385–2404, https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-14-00484.1.

- ↑ Nicholson, S. E., 2011: Dryland Climatology. Cambridge University Press, 528 pp.

- ↑ Washington, R., and Todd, M. C. (2005), Atmospheric controls on mineral dust emission from the Bodélé Depression, Chad: The role of the low level jet, Geophys. Res. Lett., 32, L17701, doi:10.1029/2005GL023597.

- ↑ Bristow, Charlie S.; Drake, Nick; Armitage, Simon (2009-04-01). "Deflation in the dustiest place on Earth: The Bodélé Depression, Chad". Geomorphology. Contemporary research in aeolian geomorphology. 105 (1): 50–58. Bibcode:2009Geomo.105...50B

- ↑ Munday, C., and Coauthors, 2022: Observations of the Turkana Jet and the East African Dry Tropics: The RIFTJet Field Campaign. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 103, E1828–E1842, https://doi.org/10.1175/BAMS-D-21-0214.1.

- ↑ Munday, C., Savage, N., Jones, R.G. et al. Valley formation aridifies East Africa and elevates Congo Basin rainfall. Nature 615, 276–279 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05662-5

- ↑ Thorncroft, C. D., H. Nguyen, C. Zhang, and P. Payrille (2011), Annual cycle of the West African monsoon: Regional circulations and associated water vapour transport, Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc., 137, 129–147.

- ↑ Nicholson, SE, Klotter, D. The Tropical Easterly Jet over Africa, its representation in six reanalysis products, and its association with Sahel rainfall. Int J Climatol. 2021; 41: 328– 347. https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.6623

- ↑ Mitchell, Todd (October 2001). "Africa Rainfall Climatology". University of Washington. Archived from the original on 4 September 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ↑ Laux, Patrick; et al. (2008). "Predicting the regional onset of the rainy season in West Africa". International Journal of Climatology. 28 (3): 329–342. Bibcode:2008IJCli..28..329L. doi:10.1002/joc.1542. S2CID 129309284.

- ↑ Laux, Patrick; et al. (2009). "Modelling daily precipitation features in the Volta Basin of West Africa". International Journal of Climatology. 29 (7): 937–954. Bibcode:2009IJCli..29..937L. doi:10.1002/joc.1852. S2CID 129107711.

- ↑ Vandervort, David (2009). "Darfur: getting ready for the rainy season". International Committee of the Red Cross. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- ↑ Mebrhatu, Mehari Tesfazgi; M. Tsubo, and Sue Walker (2004). "A Statistical Model for Seasonal Rainfall Forecasting over the Highlands of Eritrea". New directions for a diverse planet: Proceedings of the 4th International Crop Science Congress. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ↑ Alex Wynter (2009). Ethiopia: March rainy season "critical" for southern pastoralists. Thomson Reuters Foundation. Retrieved on 6 February 2009.

- ↑ The Voice (2009). "Botswana: Rainy Season Fills Up Dams". allAfrica.com. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

- ↑ "La Niña Weather Likely to Last for Months | Scoop News".

- ↑ Arivelo, T. Andry; A. Ratiarison; M. Bessafi; Rodolphe Ramiharijafy (19 December 2007). "Madagascar rainfall climatology: Extreme Phenomena" (PDF). Stanford University. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- ↑ Mngadi, Pearl; Petrus J. M. Visser; Elizabeth Ebert (October 2006). "Southern Africa Satellite Derived Rainfall Estimates Validation" (PDF). International Precipitation Working Group. p. 1. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ↑ "Skiing and Snowboarding". Tiffendell. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ↑ "UCT Mountain and Ski Club". Archived from the original on 3 June 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ↑ "Snow on Table Mountain". 20 September 2013. Archived from the original on 30 June 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ↑ "Snow Doubt…There's Snow on Table Mountain Today". 30 August 2013. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ↑ "Snow on Table Mountain: August Chill Sets In". Archived from the original on 4 June 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ↑ "Icy Weather Brings Snow to Table Mountain". Retrieved 16 February 2014.

- ↑ SABCnews.com. "Joburg covered by snow as temperature drops". Archived from the original on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 16 July 2007.

- ↑ Carrington, Dalsy (2014). "Last chance to see: Disappearing glaciers in the 'Mountains of the Moon'". 3 April 2014 CNN.

- ↑ Schneider, S. H.; et al. (2007). "19.3.3 Regional vulnerabilities". In Parry, M. L.; et al. (eds.). Chapter 19: Assessing Key Vulnerabilities and the Risk from Climate Change. Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability: contribution of Working Group II to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, UK: Print version: CUP. This version: IPCC website. ISBN 978-0-521-88010-7. Archived from the original on 12 March 2013. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- 1 2 3 Niang, I.; O. C. Ruppel; M. A. Abdrabo; A. Essel; C. Lennard; J. Padgham, and P. Urquhart, 2014: Africa. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part B: Regional Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Barros, V. R.; C. B. Field; D. J. Dokken et al. (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 1199–1265. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/WGIIAR5-Chap22_FINAL.pdf

- ↑ Kendon, Elizabeth J.; Stratton, Rachel A.; Tucker, Simon; Marsham, John H.; Berthou, Ségolène; Rowell, David P.; Senior, Catherine A. (2019). "Enhanced future changes in wet and dry extremes over Africa at convection-permitting scale". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 1794. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.1794K. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-09776-9. PMC 6478940. PMID 31015416.

- ↑ "More Extreme Weather in Africa's Future, Study Says | The Weather Channel – Articles from The Weather Channel | weather.com". The Weather Channel. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ↑ United Nations, UNEP (2017). "Responding to climate change". UNEP – UN Environment Programme. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ↑ Ofoegbu, Chidiebere; Chirwa, P. W. (19 May 2019). "Analysis of rural people's attitude towards the management of tribal forests in South Africa". Journal of Sustainable Forestry. 38 (4): 396–411. Bibcode:2019JSusF..38..396O. doi:10.1080/10549811.2018.1554495. hdl:2263/75471. S2CID 92282095.

- ↑ Boko, M. (2007). "Executive summary". In Parry, M. L.; et al. (eds.). Chapter 9: Africa. Climate change 2007: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability: contribution of Working Group II to the fourth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, UK: Print version: CUP. This version: IPCC website. ISBN 978-0-521-88010-7. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ↑ Ofoegbu, Chidiebere; Chirwa, P. W.; Francis, J.; Babalola, F. D. (3 July 2019). "Assessing local-level forest use and management capacity as a climate-change adaptation strategy in Vhembe district of South Africa". Climate and Development. 11 (6): 501–512. Bibcode:2019CliDe..11..501O. doi:10.1080/17565529.2018.1447904. hdl:2263/64496. S2CID 158887449.

- ↑ "Global Warming of 1.5 °C —". Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- ↑ European Investment Bank (6 July 2022). EIB Group Sustainability Report 2021. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5237-5.

- ↑ "Climate change triggers mounting food insecurity, poverty and displacement in Africa". public.wmo.int. 18 October 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ↑ "Global warming: severe consequences for Africa". Africa Renewal. 7 December 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ↑ Rural societies in the face of climatic and environmental changes in West Africa. Marseille: IRD éditions. 2017. ISBN 978-2-7099-2424-5. OCLC 1034784045. Impr. Jouve.

- 1 2 Collins, Jennifer M. (15 July 2011). "Temperature Variability over Africa". Journal of Climate. 24 (14): 3649–3666. Bibcode:2011JCli...24.3649C. doi:10.1175/2011JCLI3753.1.

- ↑ Conway, Declan; Persechino, Aurelie; Ardoin-Bardin, Sandra; Hamandawana, Hamisai; Dieulin, Claudine; Mahé, Gil (February 2009). "Rainfall and Water Resources Variability in Sub-Saharan Africa during the Twentieth Century". Journal of Hydrometeorology. 10 (1): 41–59. Bibcode:2009JHyMe..10...41C. doi:10.1175/2008JHM1004.1.

- ↑ World Bank Climate Change Knowledge Portal. "Kenya (Vulnerability)". Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- ↑ Sverdlik, A.; et al. (2019). "Realising the Multiple Benefits of Climate Resilience and Inclusive Development in Informal Settlements" (PDF). Retrieved 29 January 2021.

- ↑ Hirch, Aurther (November 2017). "Effects of climate change likely to be more deadly in poor African settlements".

- ↑ "Southern African Development Community: Climate Change Adaptation". www.sadc.int. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ↑ Lesolle, D. (2012). SADC policy paper on climate change: Assessing the policy options for SADC member stated (PDF).

- ↑ Climate change adaptation in SADC: A Strategy for the water sector (PDF).

- ↑ "Programme on Climate Change Adaptation, Mitigation in Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA-EAC-SADC)". Southern African Development Community. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- ↑ AFRICAN STRATEGY ON CLIMATE CHANGE (PDF). African Union. 2014.

- ↑ European Investment Bank (19 October 2022). Finance in Africa - Navigating the financial landscape in turbulent times. European Investment Bank. ISBN 978-92-861-5382-2.

- ↑ "Financing for Sustainable Development Report 2021" (PDF). UN.

- ↑ United Nations. "Population growth, environmental degradation and climate change". United Nations. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ↑ Trisos, Christopher H. "Chapter 9: Africa" (PDF). IPCC Sixth Assessment Report.