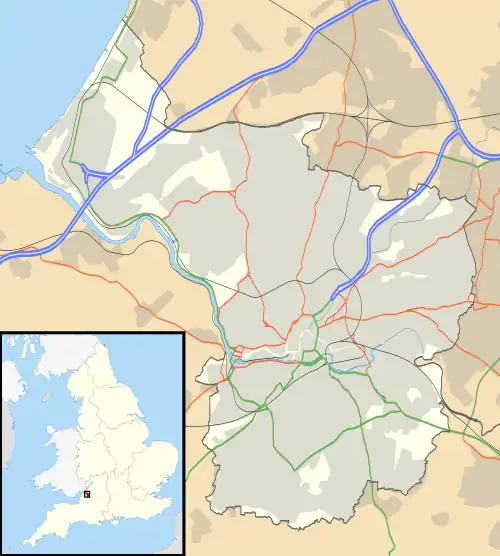

Clifton Suspension Bridge | |

|---|---|

Clifton Suspension Bridge | |

| Coordinates | 51°27′18″N 2°37′40″W / 51.4549°N 2.6279°W |

| Carries | B3129 road, cars, pedestrians and cyclists |

| Crosses | River Avon |

| Locale | Bristol |

| Maintained by | Clifton Suspension Bridge Trust |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Suspension bridge |

| Total length | 1,352 ft (412 m) |

| Width | 31 ft (9.4 m) |

| Height | 331 ft (101 m) above high water level (86 ft (26 m) above deck) |

| Longest span | 702 ft 3 in (214.05 m) |

| Clearance below | 245 ft (75 m) above high water level |

| History | |

| Opened | 1864 |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 8,800[1] |

| Toll | Vehicles £1.00 |

| Location | |

The Clifton Suspension Bridge is a suspension bridge spanning the Avon Gorge and the River Avon, linking Clifton in Bristol to Leigh Woods in North Somerset. Since opening in 1864, it has been a toll bridge, the income from which provides funds for its maintenance. The bridge is built to a design by William Henry Barlow and John Hawkshaw,[2] based on an earlier design by Isambard Kingdom Brunel. It is a Grade I listed building and forms part of the B3129 road.

The idea of building a bridge across the Avon Gorge originated in 1753. Original plans were for a stone bridge and later iterations were for a wrought iron structure. In 1831, an attempt to build Brunel's design was halted by the Bristol riots, and the revised version of his designs was built after his death and completed in 1864. Although similar in size and design, the bridge towers are not identical, the Clifton tower having side cut-outs, the Leigh tower more pointed arches atop a 110-foot (34 m) red sandstone-clad abutment. Roller-mounted "saddles" at the top of each tower allow movement of the three independent wrought iron chains on each side when loads pass over the bridge. The bridge deck is suspended by 162 vertical wrought-iron rods in 81 matching pairs.

The Clifton Bridge Company initially managed the bridge under licence from a charitable trust. The trust subsequently purchased the company shares, completing this in 1949 and took over the running of the bridge using the income from tolls to pay for maintenance. The bridge is a distinctive landmark, used as a symbol of Bristol on postcards, promotional materials, and informational web sites. It has been used as a backdrop to several films and television advertising and programmes. It has also been the venue for significant cultural events such as the first modern bungee jump in 1979, the last Concorde flight in 2003 which flew over the bridge, and a handover of the Olympic Torch relay in 2012.

History

Plans

It is unknown when the first bridge was constructed across the Avon in Bristol, but the first stone bridge, Bristol Bridge, was built in the 13th century. It had houses with shopfronts built on it to pay for its maintenance. A 17th-century illustration shows that these bridge houses were five storeys high, including the attic rooms, and that they overhung the river much as Tudor houses would overhang the street.[3] In the 1760s a bill to replace the bridge was carried through parliament by the Bristol MP Sir Jarrit Smyth.[4] By the early 18th century, increase in traffic and the encroachment of shops on the roadway made the bridge fatally dangerous for many pedestrians. A new bridge, designed by James Bridges and finished by Thomas Paty was built in 1769 and 1776. Resentment at the tolls exacted to cross the new bridge occasioned the Bristol Bridge Riot of 1793.[5] Other crossings were considered, but were restricted by Admiralty rules that stipulated that any bridge had to be at least 100 feet (30 m) above the water to allow the passage of tall-masted warships to Bristol Harbour. To achieve this, any bridge constructed between Bristol Bridge and Avon Gorge, from Hotwells to Ashton Gate, would require massive embankments and viaducts.[6] The alternative was to build across the narrowest point of the Avon Gorge, well above the height required for shipping.

In 1753 Bristolian merchant William Vick had left a bequest in his will of £1,000 (equivalent to £160,000 in 2021),[7] invested with instructions that when the interest had accumulated to £10,000 (£1,620,000), it should be used for the purpose of building a stone bridge between Clifton Down (which was in Gloucestershire, outside the City of Bristol, until the 1830s) and Leigh Woods in Somerset.[8] Although there was little development in the area before the late 18th century, as Bristol became more prosperous, Clifton became fashionable and more wealthy merchants moved to the area.[9] In 1793 William Bridges published plans for a stone arch with abutments containing factories, which would pay for the upkeep of the bridge. The French Revolutionary Wars broke out soon after the design was published, affecting trade and commerce, so the plans were shelved.[6][10] In 1811 Sarah Guppy patented a design for a suspension bridge across the gorge but this was never realised and was not submitted to the later competition.[11][12]

By 1829, Vick's bequest had reached £8,000, but it was estimated that a stone bridge would cost over ten times that.[13] A competition was held to find a design for the bridge with a prize of 100 guineas.[14] Entries were received from 22 designers, including Samuel Brown, James Meadows Rendel, William Tierney Clark and William Hazledine. Several were for stone bridges and had estimated costs of between £30,000 and £93,000. Brunel submitted four entries.[14] The judging committee rejected 17 of the 22 plans submitted, on the grounds of appearance or cost.[15] They then called in Scottish civil engineer Thomas Telford to make a final selection from the five remaining entries.[15] Telford rejected all the remaining designs, arguing that 577 feet (176 m) was the maximum possible span. Telford was then asked to produce a design himself, which he did, proposing a 110-foot-wide (34 m) suspension bridge, supported on tall Gothic towers, costing £52,000.[15][8][16]

The Bridge Committee which had been set up to look at the designs sponsored the Clifton Bridge Bill which became an Act when the Bill received the Royal Assent on 29 May 1830. The Act appointed three Trustees to carry through the purposes of the Act, with powers to appoint more up to a total not exceeding thirty five or less than twenty. The three Trustees named in the Act were the Master of the Society of Merchant Venturers, the Senior Sheriff of the City and County of Bristol and Thomas Daniel. The Act allowed a wrought iron suspension bridge to be built instead of stone, and tolls levied to recoup the cost.[16][17]

The three Trustees named in the Act met on 17 June 1830 and appointed further Trustees, bringing the total up to 23. There were additions to this number in the weeks which followed, so by early July 1830 there were 31 in all, although not everyone had been formally sworn in by that date. Others included Thomas Durbin Brice, Master of the Society of Merchant Venturers, George Daubeny, John Cave, John Scandrett Harford, George Hilhouse, Henry Bush, and Richard Guppy.[17]

The first full meeting of the Trustees was held on 22 June 1830 in the Merchants Hall in Bristol. Alderman Thomas Daniel was in the chair. 86 people had committed £17,350, an average of just over £200 each.[17]

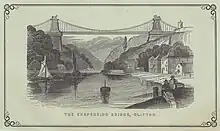

These funds raised during the first few months of 1830 were not sufficient for the construction. Despite this Brunel produced a new proposal costing £10,000 less than Telford's design and gained support for it in the local press. James Meadows Rendel, William Armstrong and William Hill also submitted new, cheaper proposals, complaining that the committee had not set a budget.[18] In 1831 a second competition was held, with new judges including Davies Gilbert and John Seaward examining the engineering qualities of the proposals. Thirteen designs were submitted; Telford's was the only one in which the chains achieved the weight per square inch required by the judges but it was rejected as being too expensive. The winner was declared to be a design by Smith and Hawkes of the Eagle Foundry in Birmingham.[19] Brunel had a personal meeting with Gilbert and persuaded him to change the decision. The committee then declared Brunel the winner and he was awarded a contract as project engineer.[20] The winning design was for a suspension bridge with fashionably Egyptian-influenced towers.[8] In 2010, newly discovered letters and documents revealed that, in producing his design, Brunel had not taken advice from his father, Sir Marc Isambard Brunel, who had offered to help. The elder Brunel had recommended including a central support for the bridge, as he did not believe a single-span bridge of such length could be constructed. His son chose to ignore his advice.[21][22]

Construction

A ceremony to mark the start of the construction works was held Monday 20 June 1831. Work started on blasting of St. Vincent's Rock, on the Clifton side of the gorge. Four months later work was halted by the Bristol riots, which took place after the House of Lords rejected the second Reform Bill, which aimed to eliminate some of the rotten boroughs and give parliamentary seats to Britain's fast growing industrial towns such as Bristol.[23] Five to six hundred young men were involved in the riots and Brunel was sworn in as a special constable. The riots severely dented commercial confidence in Bristol; subscriptions to the bridge company ceased, and along with it, further construction of the bridge.[24]

After the passing of the Act for the Great Western Railway reestablished financial confidence, work resumed in 1836, but subsequent investment proved woefully inadequate.[25] Despite the main contractors going bankrupt in 1837, the towers were built in unfinished stone.[26] To enable the transfer of materials, a 1,000-foot-long (300 m) iron bar, which was 1.25 inches (32 mm) in diameter, had been drawn by capstan across the gorge. A contract was placed with Dowlais Ironworks to supply 600 tons of bar iron, which was to be transported to the Copperhouse foundry to be forged into bar chains.[25] By 1843 funds were exhausted and another £30,000 was needed. As the work had exceeded the time limit stated in the Act, all work stopped.[27] Brunel suggested building a deep water pier at Portbury, which would make the bridge an essential road link, but funds for this scheme were not forthcoming.[25] In 1851, the ironwork was sold and used to build the Brunel-designed Royal Albert Bridge on the railway between Plymouth and Saltash.[28] The towers remained and during the 1850s intrepid passengers could cross the gorge in a basket slung from the iron bar.[27]

Brunel died in 1859, without seeing the completion of the bridge. His colleagues in the Institution of Civil Engineers felt that completion of the Bridge would be a fitting memorial, and started to raise new funds.[29] In 1860, Brunel's Hungerford suspension bridge over the Thames in London was demolished to make way for a new railway bridge to Charing Cross railway station. Its chains were purchased for use at Clifton.[30]

A revised design was made by William Henry Barlow and Sir John Hawkshaw, with a wider, higher and sturdier deck than Brunel intended, with triple chains instead of double.[29]

It has been argued that the size and technology of these revisions was so great that the credit for its design should go to Barlow and Hawkshaw.[31] The towers remained in rough stone, rather than being finished in the Egyptian style. Work on the bridge was restarted in 1862. Initially a temporary bridge was created by pulling ropes across the gorge and making a footway of wire ropes with wood planks held together with iron hoops. This was used by the workers to move a "traveller", consisting of a light frame on wheels, to transport each link individually, which would eventually make up the chains supporting the bridge.[32] The chains are anchored in tapering tunnels, 25 metres (82 ft) long,[33] on either side of the bridge and plugs of Staffordshire blue brick infilled to prevent the chains being pulled out of the narrower tunnel mouth. After completion of the chains, vertical suspension rods were hung from the links in the chains and large girders hung from these. The girders on either side then support the deck, which is 3 feet (0.91 m) higher at the Clifton end than at Leigh Woods so that it gives the impression of being horizontal. The strength of the structure was tested by spreading 500 tons of stone over the bridge. This caused it to sag by 7 inches (180 mm), but within the expected tolerances.[34] During this time a tunnel was driven through the rocks on the Leigh Woods side beneath the bridge to carry the Bristol Port Railway to Avonmouth.[32] The construction work was completed in 1864–111 years after a bridge at the site was first planned.[35]

Operation

On 8 December 1864, the bridge was lit by a combination of four electric arc lamps, magnesium flares and limelights for its ceremonial opening ceremony.[36] This was the earliest use of external electric lighting in Bristol. However, the lighting levels were inconsistent and the magnesium lamps were blown out by the wind.[37] The custom of lighting the bridge has continued with more recent events, although later thousands of electric light bulbs were attached to the bridge instead of flares.[38]

In 1860 the Clifton Bridge Company was set up to oversee the final stages of completion and manage the operation of the bridge. They paid £50 each year to the trustees who gradually purchased the shares in the company. The revenues from tolls were minimal initially as there was not much traffic; however, this increased after 1920 with greater car ownership. In 1949 the trustees purchased all the outstanding shares and debentures.[39] The bridge is managed by a charitable trust, originally formed by the Society of Merchant Venturers following Vick's bequest.[40] The trust was authorised to manage the bridge and collect tolls by Acts of Parliament in 1952, 1980 and 1986.[41] A toll of £0.50 has been levied on vehicles since 2007,[42] but the £0.05 toll that the Act allows for cyclists or pedestrians is not collected.[43] Human toll collectors were replaced by automated machines in 1975. The tolls are used to pay for the upkeep of the bridge, including the strengthening of the chain anchor points, which was done in 1925 and 1939, and regular painting and maintenance, which is carried out from a motorised cradle slung beneath the deck.[44] By 2008 over 4 million vehicles crossed the bridge each year.[39] In February 2012, the bridge trustees applied to the Department for Transport to increase the toll to £1,[42] subsequently implemented on 24 April 2014.[45]

On 1 April 1979, the first modern bungee jumps were made from the bridge by members of the University of Oxford Dangerous Sports Club.[46] In 2003 and 2004, the weight of crowds travelling to and from the Ashton Court Festival and Bristol International Balloon Fiesta put such great strain on the bridge that it was decided to close the bridge to all motor traffic and pedestrians during the events. The closure of the bridge for major annual events has continued each year since then.[47]

On 26 November 2003, the last Concorde flight (Concorde 216) flew over the bridge before landing at Filton Aerodrome.[48] In April 2006, the bridge was the centrepiece of the Brunel 200 weekend, celebrating the 200th anniversary of the birth of Isambard Kingdom Brunel. At the climax of the celebration a firework display was launched from the bridge.[49] The celebrations also saw the activation of an LED-based lighting array to illuminate the bridge.[50]

On 4 April 2009, the bridge was shut for one night to allow a crack in one of the support hangers to be repaired.[51] On 23 May 2012, the London 2012 Olympic Torch relay crossed over the bridge, where two of the torchbearers came together in a "kiss" to exchange the flame in the middle of Brunel's iconic landmark.[52] The bridge carries four million vehicles per year,[53] along part of the B3129 road.[54][55] The bridge is a Grade I listed building.[56]

In November 2011 it was announced that a new visitor centre, costing nearly £2 million, was to be built at the Leigh Woods end of the bridge to replace the temporary building currently being used. The new facilities were scheduled to be completed before the 150th anniversary of the opening, which was celebrated on 8 December 2014.[57][58] In December 2012 it was announced that the bridge had received £595,000 of funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund to improve the visitor centre.[59]

Archives

The University of Bristol Special Collections holds substantial records related to the bridge.[60] Letter books of the trustees of Clifton Suspension Bridge dated 1831–1862 are held at Bristol Archives (Ref. 12167/42-44) (online catalogue).

Engineering

Although similar in size the bridge towers are not identical in design, the Clifton tower having side cut-outs whilst the Leigh tower has more pointed arches and chamfered edges. Brunel's original plan proposed they be topped with then-fashionable sphinxes, but the ornaments were never constructed.[61]

.jpg.webp)

The 85-foot-tall (26 m) Leigh Woods tower stands atop a 110-foot (34 m) red sandstone-clad abutment. In 2002 it was discovered that this was not a solid structure but contained 12 vaulted chambers up to 35 feet (11 m) high, linked by shafts and tunnels.[62]

Roller-mounted "saddles" at the top of each tower allow movement of the chains when loads pass over the bridge. Though their total travel is minuscule, their ability to absorb forces created by chain deflection prevents damage to both tower and chain.[61][62]

The bridge has three independent wrought iron chains per side, from which the bridge deck is suspended by eighty-one matching vertical wrought-iron rods ranging from 65 feet (20 m) at the ends to 3 feet (0.91 m) in the centre.[63] Composed of numerous parallel rows of eyebars connected by bolts, the chains are anchored in tunnels in the rocks 60 feet (18 m) below ground level at the sides of the gorge.[62] The deck was originally laid with wooden planking, later covered with asphalt, which was renewed in 2009.[62] The weight of the bridge, including chains, rods, girders and deck is approximately 1,500 tons.[64]

Dimensions

Incidents

Two men were killed during the construction of the bridge.[64] In 1885, a 22-year-old woman named Sarah Ann Henley survived a suicide attempt off the bridge when her billowing skirts acted as a parachute and she landed in the thick mud banks of the tidal River Avon at low tide; she subsequently lived into her eighties.[68]

The Clifton Suspension Bridge is well known as a suicide bridge and is fitted with plaques that advertise the telephone number of Samaritans. Between 1974 and 1993, 127 people fell to their deaths from the bridge.[69] In 1998 barriers were installed on the bridge to prevent people jumping. In the four years after installation this reduced the suicide rate from eight deaths per year to four.[70] Nicolette Powell, the wife of UK rhythm and blues singer Georgie Fame, formerly the Marchioness of Londonderry, jumped to her death from the bridge on 13 August 1993.[71]

In 1957 a Filton-based RAF Vampire jet from 501 Squadron piloted by Flying officer John Greenwood Crossley flew under the deck while performing a victory roll[72] before crashing in Leigh Woods, killing the pilot.[73] The accident caused a landslip that led to the temporary closure of the nearby Bristol to Portishead railway line.[74] A helicopter from National Police Air Service Filton flew under the bridge during a search in 1997.[64][75]

On 12 February 2014 the bridge was closed to traffic due to wind for the first time in living memory.[76]

Gallery

SUSPENSA VIX VIA FIT, "The road becomes barely suspended"; Latin inscription atop Leigh Woods pier expressing the amazement of Victorian travellers on first seeing the bridge

SUSPENSA VIX VIA FIT, "The road becomes barely suspended"; Latin inscription atop Leigh Woods pier expressing the amazement of Victorian travellers on first seeing the bridge Avon Gorge and Clifton Suspension Bridge, with Giants Cave

Avon Gorge and Clifton Suspension Bridge, with Giants Cave Clifton Suspension Bridge photographed from above and north east with Clifton Observatory in the foreground

Clifton Suspension Bridge photographed from above and north east with Clifton Observatory in the foreground

Notes

- ↑ "Suspension bridge toll may double to £1". Bristol Evening Post. 12 November 2010. Archived from the original on 14 November 2010. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- ↑ Beaumont, Martin (2015). Sir John Hawkshaw 1811–1891. The Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway Society www.lyrs.org.uk. pp. 108–111. ISBN 978-0-9559467-7-6.

- ↑ Lynch 1999, p. 10.

- ↑ Bantock 2004, p. 29.

- ↑ Andrews & Pascoe 2008, p. 12.

- 1 2 Andrews & Pascoe 2008, p. 10.

- ↑ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- 1 2 3 Vaughan 2003, pp. 37–39.

- ↑ McIlwain 1996, p. 3.

- ↑ "Clifton Suspension Bridge, Gloucestershire". Heritage Trail. Archived from the original on 18 April 2012. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- ↑ Cork, Tristan (27 May 2016). "Recognition at last for the mum-of-six who designed Bristol's Clifton Suspension Bridge – not Brunel". Bristol Post. Archived from the original on 28 May 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ↑ "Did Sarah Guppy Design the Clifton Suspension Bridge?". Clifton Suspension Bridge Trust. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ↑ "The Clifton Suspension Bridge". Brunel 200. Archived from the original on 20 May 2013. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- 1 2 Andrews & Pascoe 2008, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 Andrews & Pascoe 2008, p. 18.

- 1 2 McIlwain 1996, p. 4-5.

- 1 2 3 Portman, Derek (2002). "A Business History of the Clifton Suspension Bridge". Construction History. 18: 3–20. JSTOR 41613843 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Andrews & Pascoe 2008, p. 20.

- ↑ Andrews & Pascoe 2008, p. 22.

- ↑ McIlwain 1996, p. 6-7.

- ↑ Savill, Richard (17 December 2010). "Clifton suspension bridge – with added pagoda". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ↑ Brown, Christopher. "Brunel rejected father's pagoda plan for Clifton Suspension Bridge". Bristol 24-7. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ↑ "Bristol riots". Spartacus Education. Archived from the original on 5 February 2007. Retrieved 7 March 2007.

- ↑ "Revolting riots in Queen Square". BBC Bristol. BBC. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 Andrews & Pascoe 2008, p. 32.

- ↑ Andrews & Pascoe 2008, p. 30.

- 1 2 McIlwain 1996, p. 13.

- ↑ "Royal Albert Bridge, Saltash". Engineering Timelines. Archived from the original on 4 April 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- 1 2 McIlwain 1996, p. 16.

- ↑ Andrews & Pascoe 2008, p. 34.

- ↑ Elton, Julia (13 May 2014). "Great Lives". BBC Radio 4. BBC. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

- 1 2 Andrews & Pascoe 2008, p. 36.

- ↑ Richards 2010.

- ↑ McIlwain 1996, p. 14-19.

- ↑ "Clifton Suspension Bridge". Engineering Timelines. Archived from the original on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ↑ Peter G. Lamb, Electricity in Bristol 1863-1948 (Bristol Historical Association pamphlets, no. 48, 1981), p. 1

- ↑ Christopher 2013, p. 11.

- ↑ McIlwain 1996, p. 22-25.

- 1 2 Andrews & Pascoe 2008, p. 42.

- ↑ "Brunel Collection: Clifton Suspension Bridge Trust (1830 – present) Papers". Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ↑ "Clifton Suspension Bridge Trust". Open Charities. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2013.

- 1 2 "Clifton Suspension Bridge toll to rise to £1". BBC News. 14 February 2012. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- ↑ "How much is the toll to cross the Bridge?". Clifton Suspension Bridge. Archived from the original on 14 November 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ↑ McIlwain 1996, p. 24-25.

- ↑ "Clifton Suspension Bridge toll to rise from 50p to £1". BBC News. 9 April 2014. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ↑ "History of Bungee". Aerial Extreme Sports. 2008. Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ↑ "Suspension bridge shut for events". BBC News. 29 June 2005. Retrieved 25 March 2007.

- ↑ "The Last Flight Home". Aviation Art. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ↑ "Brunel 200 Fireworks". BBC Bristol. Archived from the original on 21 April 2006. Retrieved 25 March 2007.

- ↑ "LEDs help to light Clifton Suspension Bridge". LEDs magazine. Archived from the original on 24 August 2007. Retrieved 17 May 2007.

- ↑ "Suspension bridge closed by fault". BBC. 4 April 2009. Archived from the original on 5 April 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2009.

- ↑ "Fireworks mark Olympic torch's suspension bridge crossing". BBC. 23 April 2012. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ↑ "Clifton Suspension Bridge". PBS LearningMedia. Archived from the original on 15 April 2015. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- ↑ "Bristol to Portishead Loop Cycle Route". Cycle Route. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ↑ "B3129". SABRE. Archived from the original on 13 October 2012. Retrieved 8 March 2013.

- ↑ Historic England. "Clifton Suspension Bridge (1205734)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 9 May 2006.

- ↑ "New heritage and learning centre". Clifton Suspension Bridge. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ↑ "New Clifton Suspension Bridge visitor centre planned". BBC. 8 November 2011. Archived from the original on 11 November 2011. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ↑ "£1.3m lottery windfall to enhance two of our finest Victorian landmarks". This is Bristol. Archived from the original on 23 December 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ↑ "National Archives Discovery Catalogue page, University of Bristol Special Collections". Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- 1 2 Farvis 2003.

- ↑ "Clifton Suspension Bridge". Brantacan. Archived from the original on 23 June 2007. Retrieved 17 May 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - 1 2 3 "Suspension Bridge Frequently Asked Questions". Clifton Suspension Bridge Trust. Archived from the original on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Structurae 2012.

- ↑ Andrews & Pascoe 2008, p. 5.

- ↑ "What are the dimensions of the Clifton Suspension Bridge?". Clifton Suspension Bridge Trust. Archived from the original on 21 March 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ↑ "Stories from the archives". Clifton Suspension Bridge Trust. Archived from the original on 22 October 2016. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- ↑ Nowers, M; Gunnell, D (1996). "Suicide from the Clifton Suspension Bridge in England". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 50 (1): 30–2. doi:10.1136/jech.50.1.30. PMC 1060200. PMID 8762350. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012.

- ↑ Bennewith, O; Nowers, M; Gunnell, D (2007). "Effect of barriers on the Clifton suspension bridge". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 190 (3): 266–7. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.027136. PMID 17329749. Archived from the original on 28 June 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ↑ "Pop star's wife died in fall from bridge". The Independent. 24 August 1993. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ↑ Griffiths 2012, p. 61.

- ↑ Whittell 2007, p. 151.

- ↑ "The Railway Gazette". 106. 1957: 74.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Wilkes-som, Joseph; Ballinger, Alex (7 August 2017). "Coastguard helicopter and police at Suspension Bridge incident". bristolpost.co.uk.

- ↑ "Brunel's Clifton Suspension Bridge swings in high wind". BBC News BBC News. Archived from the original on 4 March 2014.

References

- Andrews, Adrian; Pascoe, Michael (2008). Clifton Suspension Bridge. Bristol: Broadcast Books. ISBN 978-1-874092-49-0.

- Bantock, Anton (2004). Ashton Court. Stroud: Tempus/The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-3213-7.

- Christopher, John (2013). Brunel in Bristol. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1445618852.

- Griffiths, Gerald (2012). The Autobiography of an Ex-Grenadier Guardsman: Gerald Griffiths His Life and Military Background. S.l: Authorhouse. ISBN 978-1-4772-4721-1.

- Lynch, John (1999). For King and for Parliament:Bristol and the English Civil War. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7509-2021-6.

- McIlwain, John (1996). Clifton Suspension Bridge. Andover: Pitkin Guides. ISBN 978-0-85372-758-3.

- Richards, D (2010). "A critical analysis of the Clifton Suspension Bridge" (PDF). Proceedings of Bridge Engineering 2 Conference 2010 April 2010, University of Bath, Bath, UK. University of Bath. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- Structurae (2012). "Clifton Suspension Bridge". International Database and Gallery of Structures. Wilhelm Ernst & Sohn. Retrieved 10 January 2012.

- Farvis (2003). "Clifton Suspension Bridge". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- Vaughan, Adrian (2003). Isambard Kingdom Brunel: engineering knight-errant. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-5748-4.

- Whittell, Giles (2007). Spitfire Women of World War II. London: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-00-723535-3.

External links

- Official website

- "Clifton Suspension Bridge Trust, registered charity no. 205658". Charity Commission for England and Wales.

- "Brunel 200 Weekend" provided by BBC Bristol

- Clifton Suspension Bridge at www.ikbrunel.org.uk Archived 9 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Time-lapse video showing the bridge as the tide changes and night time arrives on YouTube

- Clifton Suspension Bridge Trust papers, 1829–1939 University of Bristol Library Special Collections

- 1953 newsreel of Clifton Suspension Bridge

- "Puente de Clifton en Puentemanía" (in Spanish). Retrieved 24 November 2013.