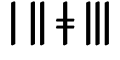

Various letters have been used to write the click consonants of southern Africa. The precursors of the current IPA letters, ⟨ǀ⟩ ⟨ǁ⟩ ⟨ǃ⟩ ⟨ǂ⟩, were created by Karl Richard Lepsius[1][2] and used by Wilhelm Bleek[3] and Lucy Lloyd, who added ⟨ʘ⟩.

Also influential were Daniel Jones, who created the letters ⟨ʇ⟩ ⟨ʖ⟩ ⟨ʗ⟩ ⟨ʞ⟩ which were promoted by the IPA from 1921 to 1989, and were used by Clement Doke[4][5] and Douglas Beach.[6]

Individual languages have had various orthographies, usually based on either the Lepsius alphabet or on the Latin alphabet. They may change over time or between countries. Latin letters, such as ⟨c⟩ ⟨x⟩ ⟨q⟩ ⟨ç⟩, have case forms; the pipe letters, ⟨ǀ⟩ ⟨ǁ⟩ ⟨ǃ⟩ ⟨ǂ⟩, do not.[7]

Multiple systems

.png.webp)

By the early 19th century, the otherwise unneeded letters ⟨c⟩ ⟨x⟩ ⟨q⟩ were used as the basis for writing clicks in Zulu by British and German missions.[8] However, for general linguistics this was confusing, as each of these letters had other uses. There were various ad hoc attempts to create letters—often iconic symbols—for click consonants, with the most successful being those of the Standard Alphabet by Lepsius, which were based on a single symbol (pipe, double pipe, pipe-acute, pipe-sub-dot) and from which the modern Khoekhoe letters ⟨ǀ⟩ ⟨ǁ⟩ ⟨ǃ⟩ ⟨ǂ⟩ descend.

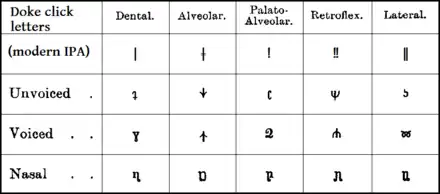

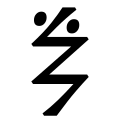

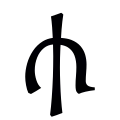

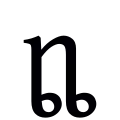

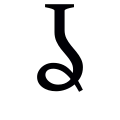

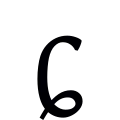

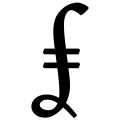

Though not clear from this image, the descenders on the nasal clicks that bend to the right bear rings, while those that bend to the left are tails as in IPA ŋ and ɲ. That is, the nasal click letters are, respectively, n with a ring on the right leg, ŋ with a ring on the left leg, n with a ring on the left leg, ɲ with a ring on the right leg, and n with rings on both legs, or, in the order of the main table,

During the First World War, Daniel Jones created the equivalent letters ⟨ʇ⟩ ⟨ʖ⟩ ⟨ʗ⟩ ⟨ʞ⟩ in response to a 1914 request to fill this gap in the IPA, and these were published in 1921 (see history of the International Phonetic Alphabet).[9]

In 1875, if not earlier, Wilhelm Bleek used the letter ⟨ʘ⟩ for bilabial clicks[10]. It was also used 1911 by Lucy Lloyd.[11]

Clement Doke expanded on Jones' letters in 1923. Based on an empirically informed conception of the nature of click consonants, he analyzed voiced and nasal clicks as separate consonants, much as voiced plosives and nasals are considered separate consonants from voiceless plosives among the pulmonic consonants, and so added letters for voiced and nasal clicks. (Jones' palatal click letter was not used, however. Jones had called it "velar", and Doke called palatal clicks "alveolar".) Doke was the first to report retroflex clicks.

Douglas Beach would publish a somewhat similar system in his phonetic description of Khoekhoe. Because Khoekhoe had no voiced clicks, he only created new letters for the four nasal clicks. Again, he didn't use Jones' "velar" click letter, but created one of his own, ⟨𝼋⟩, based on the Lepsius letter ⟨ǂ⟩ but graphically modified to better fit the design of the IPA.

| bilabial | dental | lateral | alveolar | palatal | retroflex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wuras[12] | 8 | ∧ | ⨅ | ∩ | ⅂ | |

| Boyce (1834)[13] | c | x | q | qc[14] | ||

| Knudsen (1846)[15] | ꞏ | ʼ | ʻ | ꞉ | ||

| Schreuder (1850)[16] | ||||||

| Lepsius (1853) | ǀc | ǀx | ǀʞ | ǀɔ | ||

| Lepsius (1854)[17] | ǀ | ǀǀ | ǀ̣ | ǀ́ [18] | ||

| Bleek (1857) | c | x | q | ɔ | ||

| Tindall (1858)[19] | c | x | q | v | ||

| Palaeotype (1869) | 5 | 7 | ↊ | 4 | ||

| Anthropos (1907) | p | ʇ̯ (ʇ) | ʇ (ʇ̣) | ɔ +velar ʞ | (ʇ̣) | |

| Lloyd (1911) | ʘ | ǀ | ǁ | ǃ | ǂ | |

| Jones (1921)[20] | ʇ | ʖ | ʗ | ʞ ('velar') | ||

| Doke (1925) | ʇ | ʖ | ʗ | 🡣 | ψ | |

| Engelbrecht (1928)[21] | c | x | q | ç | ||

| Beach (1938) | ʇ | ʖ | ʗ | 𝼋[22] | ||

| current IPA (1989) | ʘ | ǀ | ǁ | ǃ | ǂ | 𝼊[23] |

| typewriter substitutions | @ | / | // | ! | = | !! |

| ARA proposal (1982) | ω | ʈ | λ | ɖ | ç | |

| Linguasphere (1999) | p' | c' | l' | q' | t' | |

| Lingvarium (ca. 2005) | пъ | цъ | лъ | къ | чъ |

The African reference alphabet proposal has apparently never been used, while the Linguasphere and Lingvarium transcriptions are typewriter substitutions specific to those institutions.[24]

Besides the difference in letter shape (variations on a pipe for Lepsius, modifications of Latin letters for Jones), there was a conceptual difference between them and Doke or Beach: Lepsius used one letter as the base for all click consonants of the same place of articulation (called the 'influx'), and added a second letter or diacritic for the manner of articulation (called the 'efflux'), treating them as two distinct sounds (the click proper and its accompaniment),[25] whereas Doke used a separate letter for each tenuis, voiced, and nasal click, treating each as a distinct consonant, following the example of the Latin alphabet, where the voiced and nasal occlusives also treated as distinct consonants (p b m, t d n, c j ñ, k g ŋ).

Doke's nasal-click letters were based on the letter ⟨n⟩, continuing the pattern of the pulmonic nasal consonants ⟨m ɱ n ɲ ɳ ŋ ɴ⟩. For example, the letter for the dental nasal click is ⟨ȵ⟩; the alveolar is similar but with the curl on the left leg, the lateral has a curl on both legs, and the palatal and retroflex are ⟨ŋ⟩ ⟨ɲ⟩ with a curl on their free leg: ⟨![]() ⟩ ⟨

⟩ ⟨![]() ⟩ ⟨

⟩ ⟨![]() ⟩ ⟨

⟩ ⟨![]() ⟩ ⟨

⟩ ⟨![]() ⟩. The voiced-click letters are more individuated, a couple were simply inverted versions of the tenuis-click letters. The tenuis–voiced pairs were dental ⟨ʇ ɣ⟩ (the letter ⟨ɣ⟩ had not yet been added to the IPA for the voiced velar fricative), alveolar ⟨ʗ 𝒬⟩, retroflex ⟨ψ ⫛⟩,[26] palatal ⟨🡣 🡡⟩) and lateral ⟨ʖ ➿︎⟩. A proposal to add Doke's letters to Unicode was not approved.[27]

⟩. The voiced-click letters are more individuated, a couple were simply inverted versions of the tenuis-click letters. The tenuis–voiced pairs were dental ⟨ʇ ɣ⟩ (the letter ⟨ɣ⟩ had not yet been added to the IPA for the voiced velar fricative), alveolar ⟨ʗ 𝒬⟩, retroflex ⟨ψ ⫛⟩,[26] palatal ⟨🡣 🡡⟩) and lateral ⟨ʖ ➿︎⟩. A proposal to add Doke's letters to Unicode was not approved.[27]

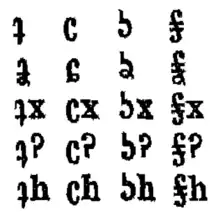

Beach wrote on Khoekhoe and so had no need for letters for the voiced clicks; he created letters for nasal clicks by adding a curl to the bottom of the tenuis-click letters: ⟨𝼌 𝼏 𝼍 𝼎⟩.

Doke and Beach both wrote aspirated clicks with an h, ⟨ʇh ʗh ʖh 𝼋h⟩, and the glottalized nasal clicks as an oral click with a glottal stop, ⟨ʇʔ ʗʔ ʖʔ 𝼋ʔ⟩. Beach also wrote the affricate contour clicks with an x, ⟨ʇx ʗx ʖx 𝼋x⟩.

Transcribing voicing, nasalization and the velar–uvular distinction

Doke had run "admirable" experiments establishing the nature of click consonants as unitary sounds. Nonetheless, Bleek in his highly influential work on Bushman languages rejected Doke's orthography on theoretical grounds, arguing that each of Doke's letters stood for two sounds, "a combination of the implosive sound with the sound made by the expulsion of the breath" (that is, influx plus efflux), and that it was impossible to write the clicks themselves in Doke's orthography, as "we cannot call [the implosive sounds] either unvoiced, voiced, or nasal."[28] Bleek therefore used digraphs based on the Lepsius letters, as Lepsius himself had done for the same reason. However, linguists have since come down on the side of Doke and take the two places of articulation to be inherent in the nature of clicks, because both are required to create a click: the 'influx' cannot exist without the 'efflux', so a symbol for an influx has only theoretical meaning just as a symbol like ⟨D⟩ for 'alveolar consonant' does not indicate any actual consonant. Regardless, today separate letters like Doke's are not provided by the IPA (or other systems), and linguists resort to diacritics that would not be used for non-click consonants. (For example, no-one transcribes a alveolar nasal stop [n] as ⟨ⁿt⟩ or ⟨t̃⟩ analogous to the way one writes a dental nasal click as ⟨ⁿǀ⟩ or ⟨ǀ̃⟩ in current IPA or as ⟨ⁿʇ⟩ or ⟨ʇ̃⟩ in pre-Kiel IPA.)

Summarized below are the common means of representing voicing, nasalization and dorsal place of articulation, from Bleek's digraphs reflecting an analysis as co-articulated consonants, to those same letters written as superscripts to function as diacritics, reflecting an analysis as unitary consonants, to the more common IPA combining diacritics for voicing and nasalization. Because the last option cannot indicate the posterior place of articulation, it does not distinguish velar from uvular clicks. The letter Ʞ is used here as a wildcard for any click letter.

| Velar | Uvular | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tenuis | Voiced | Nasal | Tenuis | Voiced | Nasal | |

| Coarticulation analysis | k͡Ʞ | ɡ͡Ʞ | ŋ͡Ʞ | q͡Ʞ | ɢ͡Ʞ | ɴ͡Ʞ |

| Superscript diacritics, unitary analysis | ᵏꞰ | ᶢꞰ | ᵑꞰ | 𐞥Ʞ | 𐞒Ʞ | ᶰꞰ |

| Combining diacritics, unitary analysis | Ʞ | Ʞ̬ | Ʞ̬̃ | |||

A distinction may be made between ⟨ᵏꞰ⟩ for an inaudible rear articulation, ⟨Ʞᵏ⟩ for an audible one, and ⟨Ʞ͡k⟩ for a notably delayed release of the rear articulation.

Historical orthographies

Written languages with clicks generally use an alphabet either based on the Lepsius alphabet, with multigraphs based on the pipe letters for clicks, or on the Zulu alphabet, with multigraphs based on c q x for clicks. In the latter case, there have been several conventions for the palatal clicks. Some languages have had more than one orthography over the years. For example, Khoekhoe has had at least the following, using dental clicks as an example:

| Modern | ǀguis | ǀa | ǀham | ǀnu |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beach (1938) | ʇuis | ʇʔa | ʇham | 𝼍u |

| Tindall (1858) | cguis | ca | cham | cnu |

Historical roman orthographies have been based on the following sets of letters:

| dental | alveolar | lateral | palatal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xhosa (1834)[13] | c | q | x | qc[29] |

| Khoekhoe (1858) | c | q | x | v |

| Juǀʼhoan (1987–1994) | c | q | x | ç |

| Naro (2001–present) | c | q | x | tc[30] |

There are two principal conventions for writing the manners of articulation (the 'effluxes'), which are used with both the Lepsius and Zulu orthographies. One uses g for voicing and x for affricate clicks; the other uses d for voicing and g for affricate clicks. Both use n for nasal clicks, but these letters may come either before or after the base letter. For simplicity, these will be illustrated across various orthographies using the lateral clicks only.

| tenuis | voiced | nasal | glottalized | aspirated | affricated | affricated ejective | voiceless nasal | murmured | murmured nasal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zulu | > ca. 1850 | x | xg[31] | xn | xh | ||||||

| Khoekhoe | modern | ǁg | ǁn | ǁ | ǁkh | ǁh | |||||

| 1858 | xg[32] | xn | x | xkh | xh | ||||||

| Naro | > 2001 | x | dx | nx | xʼ | xh | xg | xgʼ | |||

| Juǀʼhoan | modern | ǁ | gǁ | nǁ | ǁʼ | ǁh | ǁx, gǁx | ǁk, gǁk | ǁʼh | gǁh | nǁh |

| 1975 | ǁxʼ, gǁxʼ | nǁʼh | |||||||||

| 1987 | x | dx | nx | xʼ | xh | xg, dxg | xgʼ, dxgʼ | xʼh | dxh | nxh | |

| Hadza | x | nx | xx | xh | |||||||

| Sandawe | x | gx | nx | xʼ | xh | ||||||

Gallery

The Zulu click letters of the Norwegian mission:

c

c x

x q

q

Doke's letters for voiceless clicks:

c

c x

x q

q v

v

Doke's letters for voiced clicks:

gc

gc gx

gx gq

gq gv

gv

Doke's letters for nasal clicks:

nc

nc nx

nx nq

nq nv

nv

Beach's letters for voiceless clicks:

c

c x

x q

q v

v

Beach's letters for nasal clicks:

nc

nc nx

nx nq

nq nv

nv

Post-Kiel IPA:

c

c x

x q

q v

v

Long and short glyphs:

References

- ↑ Lepsius, C. R. (1855). Das allgemeine linguistische Alphabet: Grundsätze der Übertragung fremder Schriftsysteme und bisher noch ungeschriebener Sprachen in europäische Buchstaben. Berlin: Verlag von Wilhelm Hertz.

- ↑ Lepsius, C. R. (1863). Standard Alphabet for Reducing Unwritten Languages and Foreign Graphic Systems to a Uniform Orthography in European Letters (2nd ed.). London/Berlin.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Bleek, Wilhelm. A Comparative Grammar of South African Languages. Vol. (1862: Part I, 1869: Part II). London: Trübner & Co.

- ↑ Doke, Clement M. (1925). "An outline of the phonetics of the language of the ʗhũ̬꞉ Bushman of the North-West Kalahari". Bantu Studies. 2: 129–166. doi:10.1080/02561751.1923.9676181.

- ↑ Doke, Clement M. (1969) [1926]. The phonetics of the Zulu language. Johannesburg: University of the Witwatersrand Press.

- ↑ Beach, Douglas Martyn (1938). The phonetics of the Hottentot language. London: W. Heffer & Sons.

- ↑ The original Lepsius letters actually did have case forms. For example, Lepsius (1855, p. 49) wrote Amaxhosa and Xhosa as Amaııósa and 𝖨𝖨ósa.

- 1 2 3 The Norwegian mission to the Zulu used ⟨ϟ⟩ (a z-like zig-zag) for c (perhaps related to the use of both z and c for dental affricates), a double ϟ (a ξ-like zigzag) for x (perhaps not coincidentally, Greek ξ is transcribed x), and the same letter with an umlaut for q.

Zulu click letters of the Norwegian mission

Zulu click letters of the Norwegian mission - ↑ Breckwoldt, G. H. (1972). "A Critical Investigation of Click Symbolism". In Rigault, André; Charbonneau, René (eds.). Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress of Phonetic Sciences. The Hague and Paris: Mouton. p. 285. doi:10.1515/9783110814750-017. ISBN 9783110814750.

- ↑ Bleek, W. H. I (1875). A brief account of Bushman folk-lore and other texts. London: Trübner & Co.

- ↑ Bleek, Wilhelm H. I.; Lloyd, L. C. (1911). Specimens of Bushman Folklore. London: George Allen & Company.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ↑ Katechismus (Catechism of the !Kora language), undated manuscript revision of 1815 edition, which did not have a coherent transcription for clicks.

- 1 2 William Binnington Boyce (1834). A grammar of the Kafir language. London.

- ↑ Identified by Lepsius as equivalent to his ⟨𝗅́⟩

- ↑ Hans Christian Knudsen (1846). .ʻGai.꞉Hoas sada ʻKub Jesib Kristib dis, .zi ʼNaizannati. Cape Town.

- ↑ HPS Schreuder (1850). Grammatik for Zulu-Sproget. Christiania.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ The Lepsius letter is a short vertical pipe, with neither ascender nor descender—that is, of the same height as the letter n–nor serifs. In Krönlein it has a short ascender, the height of the letter t, and moreover in Krönlein the four pipe letters are always inclined, like the letters in italic type.

- ↑ The double-barred pipe was proposed by the Rhenish Mission Conference in 1856 and quickly replaced Lepsius's pipe with acute accent. (Brugman, 2009, Segments, Tones and Distribution in Khoekhoe Prosody. PhD dissertation, Cornell.)

- ↑ Tindall (1858) A grammar and vocabulary of the Namaqua-Hottentot language

Tindall's full paradigm is,- c ch ck cg ckh cn

- q qh qk qg qkh qn

- x xh xk xg xkh xn

- v vh vk vg vkh vn

- ↑ L'écriture phonétique internationale (2nd ed.)

- ↑ J.A. Engelbrecht, 1928, Studies oor Korannataal. Annale van die Universiteit van Stellenbosch. Cape Town.

- ↑ Approximately ⨎.

- ↑ The letter ⟨𝼊⟩ (ǃ̢) is 'implicit' in the IPA but is not included in the summary IPA chart. It is uncommon, and ad hoc ⟨‼⟩ is often used in the literature.

- ↑ Linguasphere found the Khoisanist/IPA letters to be impractical for sorting and with their database, and so substituted them with p', c', q', l', t'. These occur with the usual accompaniments, for sequences such as L'xegwi, Nc'hu, C'qwi, and Q'xung. Lingvarium did something similar for Cyrillic.

- ↑ Lepsius explained his system as follows:

Essential to the [clicks] is the peculiarity of stopping in part, and even drawing back the breath, which appears to be most easily expressed by a simple bar 𝗅. If we connect with this our common marks for the cerebral [i.e. retroflex: the sub-dot] or the palatal [i.e. the acute accent], a peculiar notation is wanted only for the lateral, which is the strongest sound. We propose to express it by two bars 𝗅𝗅. As the gutturals [i.e. posterior articulations] evidently do not unite with the clicks into one sound, but form a compound sound, we may make them simply to follow, as with the diphthongs.

— Lepsius (1863:80–81)

— Lepsius (1863:80–81) - ↑ In Doke's publications there is no ascender on the middle stroke, as was common in sans-serif ('grotesk') fonts of the day, and as seen in modern Arial font.

- ↑ Michael Everson (2004-06-10). "Proposal to add phonetic click characters to the UCS" (PDF). ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2, Document N2790. Retrieved 2013-10-07.

- ↑ D. F. Bleek (1923). "Note on Bushman Orthography". Bantu Studies. 2 (1): 71–74. doi:10.1080/02561751.1923.9676174.

- ↑ reported from a few words, not used in modern publication

- ↑ a typewriter-friendly variant of the Juǀʼhoan convention of ç, which had initially been used for Naro as well.

- ↑ slack voiced

- ↑ and possible ⟨xk⟩, which is conflated with xg in the modern language