| Clerkenwell explosion | |

|---|---|

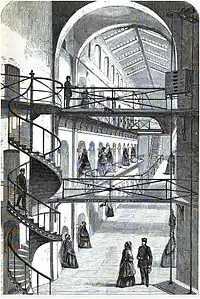

The House of Detention in Clerkenwell after the bombing; seen from within the prison yard | |

| Location | Clerkenwell, London |

| Date | 13 December 1867 (GMT) |

Attack type | Explosion |

| Weapons | 200–548 pounds (91–249 kg) Gunpowder kegs[1] |

| Deaths | 12 |

| Injured | 120 |

| Perpetrator | Irish Republican Brotherhood |

The Clerkenwell explosion, also known as the Clerkenwell Outrage, was a bombing in London on 13 December 1867. The Irish Republican Brotherhood, nicknamed the "Fenians", exploded a bomb to try to free one of their members being held on remand at Clerkenwell Prison. The explosion damaged nearby houses, killed 12 people and left 120 injured.[2] None of the prisoners escaped. The event was described by The Times the following day as "a crime of unexampled atrocity", and compared to the "infernal machines" used in Paris in 1800 and 1835 and the Gunpowder Treason of 1605. The bombing was later described as the most infamous action carried out by the Fenians in Britain in the 19th century. It enraged the public, causing a backlash of hostility in Britain which undermined efforts to establish home rule or independence for Ireland.

Background

The whole of Ireland had been under British rule since the end of the Nine Years' War in 1603. The Irish Republican Brotherhood was founded on 17 March 1858 with the aim of establishing an independent democratic republic in Ireland, and the Fenian Brotherhood, ostensibly the American wing of the Irish Republican Brotherhood, was founded in New York in 1859. The Irish Republican Brotherhood was a revolutionary fraternal organisation, rather than an insurrectionary conspiracy. It had an estimated 100,000 members by 1865, and was carrying out frequent acts of violence in metropolitan Britain.

In 1867, the Fenians were preparing to launch an armed uprising against British rule in Ireland, but their plans became known to the authorities, and members of the movement's leadership were arrested and convicted. Two succeeded in evading the police and fled to England, but they were arrested in Manchester and held in custody. On 18 September 1867, while they were being transferred from the courthouse to Belle Vue Gaol, the police van in which they were being transported was intercepted and they were freed. Police Sergeant Charles Brett was shot dead during the escape. Five suspected of involvement in the escape were tried for murder and sentenced to death. One was pardoned, and one had his sentence commuted, but the remaining three were hanged at Salford Gaol on the morning of Saturday 23 November 1867.

Three days earlier, on 20 November 1867, Ricard O'Sullivan Burke and his companion Joseph Casey were arrested in Woburn Square in London. Burke had purchased weapons for the Fenians in Birmingham. Burke was charged with treason and Casey with assaulting a constable. They were remanded in custody pending trial, and imprisoned at the Middlesex House of Detention, also known as Clerkenwell Prison (formerly the site of Clerkenwell Bridewell and the New Prison). (The prison was demolished in 1890; the Hugh Myddleton School building now stands on the site and has been converted into flats; a plaque commemorates the events.) In the previous weeks, a series of meetings of thousands of people regarding the three men convicted of Brett's murder had been held nearby on Clerkenwell Green, with a deputation sent to the Home Office and petition to Queen Victoria seeking clemency. A march from Clerkenwell Green to Hyde Park was held on Sunday 24 November, preceded by a black banner quoting from Robert Burns's 1784 poem Man was made to mourn: A Dirge: "Man's inhumanity to man makes countless thousands mourn."

Bombing

Burke's Republican colleagues tried to free him on Thursday 12 December, without success. They tried to blow a hole in the prison wall while the prisoners were exercising in the prison yard, but their bomb failed to explode. They tried again at about 3:45 pm the following day, 13 December, using a barrel of gunpowder concealed on a costermonger's barrow. The explosion demolished a 60 feet (18 m) section of the wall, but no one escaped: the prison authorities had been forewarned and the prisoners were exercised earlier in the day, so they were locked in their cells when the bomb exploded. The blast also damaged several nearby tenement houses on Corporation Lane (now Corporation Row) on the opposite side of the road, killing 12 people and causing many injuries, with estimates ranging from around 30 to over 120.

Trial

Charges were laid against eight, but two turned Queen's evidence. Michael Barrett and five others were tried at the Old Bailey from Monday 20 to Monday 27 April 1868. Lord Chief Justice Cockburn and Mr Baron Bramwell presided with a jury. The prosecution was led by the Attorney General Sir John Karslake and the Solicitor General Sir Baliol Brett supported by Hardinge Giffard QC and two junior counsel. Defence barristers included Montagu Williams and Edward Clarke.

Barrett, a native of County Fermanagh, protested his innocence, and some witnesses testified that he was in Scotland on 13 December, but another identified him as being present at the scene. Two defendants were acquitted on the instructions of the presiding judges in the course of the trial, leaving four before the jury. After deliberating for 2½ hours, three of the defendants were acquitted, but Barrett was convicted of murder at around 6:30pm on 27 April, and sentenced to death. Further enquiries into his claim to have been in Glasgow at the time of the bombing were unable to disturb the sentence, and Barrett was hanged by William Calcraft on the morning of Tuesday 26 May 1868 outside Newgate Prison. He was the last man to be publicly hanged in England, with the practice being ended from 29 May 1868 by the Capital Punishment Amendment Act 1868.

The trial of Burke and Casey, and a third defendant, Henry Shaw aka Mullady, began on 28 April, all charged with treason, before Mr Baron Bramwell and Mr Justice Keating and a jury. The prosecution claimed that Burke had been involved in finding arms for the Fenians in Birmingham in late 1865 and early 1866, where he was using the name "Edward C Winslow".

After a period in the USA, he returned to Liverpool to take part in the preparations for a plan to storm Chester Castle, and then in Ireland. After court hearings on 28, 29 and 30 April, the case against Casey was withdrawn, but Burke and Mullady were found guilty of treason on 30 April, and sentenced to 15 years and 7 years of penal servitude respectively. Burke protested that he was not a subject of the Queen, but a soldier of the United States, but evidence was provided that his mother and sister lived in Ireland, and he was convicted nonetheless.

Aftermath

This bombing enraged the British public, souring relations between England and Ireland and causing a panic over the Fenian threat. The radical, Charles Bradlaugh, condemned the incident in his newspaper the National Reformer as an act "calculated to destroy all sympathy, and to evoke the opposition of all classes". The bombing had a traumatic effect on British working-class opinion. Karl Marx, then living in London, observed:

The London masses, who have shown great sympathy towards Ireland, will be made wild and driven into the arms of a reactionary government. One cannot expect the London proletarians to allow themselves to be blown up in honour of Fenian emissaries.

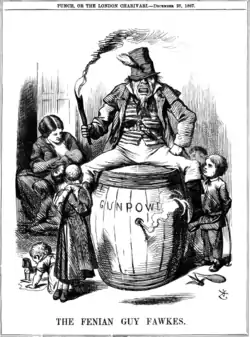

A cartoon by John Tenniel published in Punch magazine on 28 December 1867 shows the "Fenian Guy Fawkes" sitting on a barrel of gunpowder with a lighted match, surrounded by innocent women and children.

The day before the explosion, the Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, had banned all political demonstrations in London in an attempt to put a stop to the weekly meetings and marches that were being held in support of the Fenians, with a similar vice-regal declaration in Ireland. Disraeli had feared that the ban might be challenged, but the explosion had the effect of turning public opinion in his favour. After the explosion, he advocated the suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act in Britain, as was already the case in Ireland, and wider security measures were introduced. Thousands of special constables were enlisted to assist the police.

The Metropolitan Police formed a Special Irish Branch at Scotland Yard in March 1883, initially as a small section of the Criminal Investigation Department, to monitor Fenian activity. Queen Victoria, reportedly irritated that only one man was convicted for the bombing, wrote to Home Secretary Gathorne Hardy observing that she was "beginning to wish" that perpetrators of such crimes "be lynch-lawed on the spot".[3]

Liberal leader William Ewart Gladstone, then in opposition, announced his concern about Irish grievances within days of the explosion, and said that it was the duty of the British people to remove them. This act powerfully influenced Gladstone in deciding that the Anglican Church of Ireland should be disestablished as a concession to Irish disaffection. Later, he said that it was the Fenian action at Clerkenwell that turned his mind towards Home Rule. When Gladstone discovered at Hawarden later that year that Queen Victoria had invited him to form a government he famously stated, "my mission is to pacify Ireland".

In April 1867, the supreme council of the Irish Republican Brotherhood condemned the Clerkenwell Outrage as a "dreadful and deplorable event",[4] but the organisation returned to bombings in Britain in 1881 to 1885, with the Fenian dynamite campaign.[5] The impact of the event was referred to over 50 years later, when a review of James Joyce's novel Ulysses in the Quarterly Review in October 1922 described the book as "an attempted Clerkenwell explosion in the well-guarded, well-built, classical prison of English literature".[6]

On 24 September 1877 Charles Stewart Parnell MP opined to his constituents that "No amount of eloquence could achieve what the fear of an impending insurrection, what the Clerkenwell explosion and the shot in the police van [Manchester Martyrs incident] had achieved."[7] Parnell also attributed the explosion and the Manchester Martyrs incident as leading to "some measure of protection being given to the Irish tenant" and the Church of England being "disestablished and disendowed" in Ireland.[8]

References

- ↑ Bonner, David (2007). Executive Measures, Terrorism and National Security: Have the Rules of the Game Changed?. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 9. ISBN 9780754647560.

- ↑ "London Today - 1867: Twelve killed in prison break blast". Archived from the original on 13 October 2013. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- ↑ Quoted in Can Human Rights Survive? Archived 8 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Conor Gearty, p.99

- ↑ The Making of Ireland: A History, James Lydon, p. 308

- ↑ Whelehan, Niall (2012). The Dynamiters: Irish Nationalism and Political Violence in the Wider World 1867–1900. Cambridge.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Hand, Derek (2011). "A History of the Irish Novel: Interchapter 4 - James Joyce's Ulysses". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 5 April 2023.

- ↑ The Life of Charles Stewart Parnell 1846-1891 by R. Barry O'Brien, page 150

- ↑ Lyons, F. S. L. (1973). "The Political Ideas of Parnell". The Historical Journal. 16 (4): 749–775. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00003939. JSTOR 2638281. S2CID 153781140. Archived from the original on 12 November 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2021.

Sources

- thevictorianist.blogspot.co.uk

- victoriancalendar.blogspot.co.uk

- nowrigglingoutofwriting.wordpress.com

- Irish Freedom, Richard English, p. 181-2

- Victorian Sensation: Or the Spectacular, the Shocking and the Scandalous in Nineteenth-Century Britain, Michael Diamond, p. 56-7

- Ireland's Terrorist Dilemma, Yonah Alexander, Alan O'Day, 53-6

- An explosive trial, part 1

- An explosive trial, part 2

- The last public hanging, information-britain.co.uk

- Victorian Hangings: Michael Barrett, truecrimelibrary.com

- The Fenian Prisoners at the Bow Street Police Court , Museum of London

- Fenian explosion at Clerkenwell Prison, Museum of London

- House of detention, Clerkenwell after an explosion, Museum of London

- History of the Metropolitan Police: The Fenians and the IRA Archived 27 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Metropolitan Police

- Irish Political Prisoners, 1848–1922: Theatres of War, Seán McConville, p. 136-138, 260–261

- Joyce's Ulysses: A Reader's Guide, Sean Sheehan, p. 99

- The Making of Ireland: From Ancient Times to the Present, James Lydon, p. 308

- Contemporary news reports:

- London, Saturday, 14 December 1867 – The Times, Saturday, 14 Dec 1867; pg. 6; Issue 25994; col D

- Central Criminal Court, 20 April: The Fenian Trials – The Times, Tuesday, 21 Apr 1868; pg. 11; Issue 26104; col A

- Central Criminal Court, 21 April: The Fenian Trials – The Times, Wednesday, 22 Apr 1868; pg. 11; Issue 26105; col B

- Central Criminal Court, 20 April [sic]: The Fenian Trials – The Times, Thursday, 23 Apr 1868; pg. 11; Issue 26106; col B

- Central Criminal Court, 23 April: The Fenian Trials – The Times, Friday, 24 Apr 1868; pg. 11; Issue 26107; col C

- Central Criminal Court, 24 April: The Fenian Trials – The Times, Saturday, 25 Apr 1868; pg. 11; Issue 26108; col A

- Central Criminal Court, 25 April: The Fenian Trials – The Times, Monday, 27 Apr 1868; pg. 11; Issue 26109; col B

- Central Criminal Court, 27 April: The Fenian Trials – The Times, Tuesday, 28 Apr 1868; pg. 11; Issue 26110; col C

- Central Criminal Court, 28 April: The Fenian Trials – The Times, Wednesday, 29 Apr 1868; pg. 11; Issue 26111; col B

- Central Criminal Court, 29 April. The Fenian Trials – The Times, Thursday, 30 Apr 1868; pg. 11; Issue 26112; col C

- Central Criminal Court, 30 April. The Fenian Trials – The Times, Friday, 1 May 1868; pg. 11; Issue 26113; col B