| Cleomenean War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

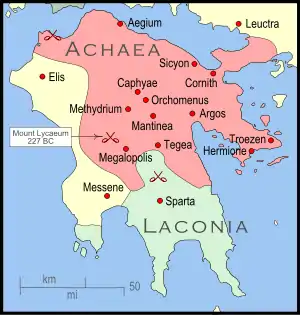

Greece at around the time of the Cleomenean War | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Sparta, Elis |

Achaean League, Macedonia | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Cleomenes III |

Aratus, Antigonus III Doson | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| ~20,000 (at largest muster) | ~30,000 (at largest muster) | ||||||||

The Cleomenean War[3] (229/228–222 BC) was fought between Sparta and the Achaean League for the control of the Peloponnese. Under the leadership of king Cleomenes III, Sparta initially had the upper hand, which forced the Achaean League to call for help the Macedonian king Antigonos Doson, who decisively defeated Cleomenes in the battle of Sellasia in 222.

In 235 BC, Cleomenes III (r. 235–222 BC) ascended the throne of Sparta and began a program of reform aimed at restoring traditional Spartan discipline while weakening the influence of the ephors, elected officials who, though sworn to uphold the rule of Sparta's kings, had by the time of Cleomenes come to wield extraordinary political power in the Spartan system. When, in 229 BC, the ephors sent Cleomenes to seize a town on the border with Megalopolis, the Achaeans declared war. Cleomenes responded by ravaging Achaea. At Mount Lycaeum he defeated an army under Aratus of Sicyon, the strategos of the Achaean League, that had been sent to attack Elis, and then routed a second army near Megalopolis.

In quick succession, Cleomenes cleared the cities of Arcadia of their Achaean garrisons, before crushing another Achaean force at Dyme. Facing Spartan domination, Aratus was forced to turn to Antigonus III Doson (r. 229–221 BC) of Macedon. In return for Macedonian assistance, the Achaeans were obliged to surrender the citadel overlooking Corinth to Antigonus. Cleomenes eventually invaded Achaea, seizing control of Corinth and Argos, but was forced to retreat to Laconia when Antigonus arrived in the Peloponnese. Cleomenes fought the Achaeans and the Macedonians at Sellasia, where the Spartans were routed. He then fled to the court of his ally, Ptolemy III of Egypt (r. 246–222 BC), where he ultimately committed suicide in the wake of a failed revolt against the new Pharaoh, Ptolemy IV (r. 221–205 BC).

Prelude

Cleomenes III ascended the throne of Sparta in 236 BC or 235 BC, after deposing his father, Leonidas II. His accession to power ended a decade-long period of heightened conflict between the two royal families. Sparta's ancient dual kingship was explained by the founding legend that the original conquerors of Sparta were twin brothers and their descendants shared Sparta. During the turmoil, Leonidas II had executed his rival king, the reformist Agis IV.[4]

In 229 BC, Cleomenes took the important cities Tegea, Mantineia, Caphyae, and Orchomenus in Arcadia, who had by then allied themselves with the Aetolian League, a powerful Greek confederation of city states in central Greece. Historians Polybius and Sir William Smith claim that Cleomenes seized the cities by treachery; however, Richard Talbert, who translated Plutarch's account of Sparta, and historian N. G. L. Hammond say Cleomenes occupied them at their own request.[5] Later that year, the ephors sent Cleomenes to seize the Athenaeum, near Belbina. Belbina was one of the entrance points into Laconia and was disputed at the time between Sparta and Megalopolis. Meanwhile, the Achaean League summoned a meeting of her assembly and declared war against Sparta. Cleomenes in return fortified his position.

Aratus of Sicyon, the strategos of the Achaean League, tried to re-take Tegea and Orchomenus in a night attack. Efforts from inside the city failed, though, and Aratus quietly retreated, hoping to remain unnoticed.[5][Note 1] Cleomenes nonetheless discovered the plan and sent a message to Aratus asking about the goal of his expedition. Aratus replied that he had come to stop Cleomenes from fortifying Belbina. Cleomenes responded to this by saying: "If it's all the same to you, write and tell me why you brought along those torches and ladders."[9]

Early years and Spartan success

After fortifying Belbina, Cleomenes advanced into Arcadia with 3,000 infantry and a few cavalry. However, he was called back by the ephors, and this retreat allowed Aratus to seize Caphyae as soon as Cleomenes returned to Laconia.[10] Once this news reached Sparta, the ephors sent Cleomenes out again; he managed to capture the Megalopian city Methydrium before ravaging the territory surrounding Argos.[11]

Around this time, the Achaean League sent an army under a new strategos—Aristomachos of Argos, who had been elected in May 228 BC—to meet Cleomenes in battle. The Achaean army of 20,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry advanced on the 5,000-strong Spartan army at Pallantium. Aratus, who had accompanied Aristomachos, advised him to retreat because even 20,000 Achaeans were no match for 5,000 Spartans.[11] Aristomachos, listening to Aratus' advice, retreated with the Achaean army.

Meanwhile, Ptolemy III of Egypt, who had been an ally of the Achaean League in their wars against Macedon, shifted his financial support to Sparta. Ptolemy made this decision after calculating that a resurgent Sparta would be a more valuable ally against Macedon than a failing Achaean League.[12]

In May 227 BC, Aratus was once again elected strategos and attacked Elis. The Eleans appealed to Sparta for aid; as the Achaeans were returning from Elis, Cleomenes attacked and routed their entire army near Mount Lycaeum. Taking advantage of a rumour that he had been killed during the fighting, Aratus attacked and seized Mantinea.[13]

Meanwhile, the Eurypontid King of Sparta Eudamidas III, son of Agis IV, died. Pausanias, the Greek writer, claims that Cleomenes had him poisoned.[14] In order to strengthen his position against the ephors, who were opposed to his expansionist policy,[10] Cleomenes recalled his uncle Archidamus V from his exile in Messene to ascend the Eurypontid throne, but as soon as Archidamus returned to the city, he was assassinated. Cleomenes' involvement in the plot is unclear, since ancient sources contradict each other: Polybius claims that Cleomenes ordered the murder, but Plutarch disagrees.[15]

Battle of Ladoceia and reforms

Later in 227 BC, Cleomenes bribed the ephors to allow him to continue his campaign against the Achaeans. Having succeeded with his bribe, Cleomenes advanced into the territory of Megalopolis and captured the village of Leuctra. In response, an Achaean army arrived, relieved the city, and inflicted a minor defeat on the Spartan army based nearest the city walls. Cleomenes was therefore obliged to retreat with his troops across a series of ravines. Aratus ordered the Achaeans not to pursue the Spartans across the ravine, but Lydiadas of Megalopolis disobeyed the order and charged with the cavalry in pursuit of the Spartans. Taking advantage of the difficult terrain and the scattered cavalry, Cleomenes sent his Cretan and Tarentine soldiers against Lydiadas. They routed the cavalry, and Lydiadas was amongst the dead. The Spartans, encouraged by these events, charged against the main Achaean forces and defeated the entire army. The Achaeans were so outraged and demoralized by Aratus' failure to support Lydiadas that they made no further attacks in that year.[16]

Cleomenes, now confident of the strength of his position, began plotting against the ephors. He first recruited his stepfather, persuading him of the need to do away with the ephors. Cleomenes contended they could then make the ephors' property common to all citizens and work toward the achievement of Spartan supremacy in Greece. Having won over his stepfather, Cleomenes started preparing his revolution. Employing the men he considered most likely to oppose him (probably in an attempt to get them killed), he captured Heraea and Asea. He also brought in food for the citizens of Orchomenus—which the Achaeans were besieging—before camping outside Mantinea. This campaign exhausted his opponents, who asked to remain in Arcadia so they could rest. Cleomenes then advanced upon Sparta with his mercenaries and sent some loyal followers to slay the ephors. Four of the five ephors were killed; the sole survivor was Agylaeus, who managed to escape and sought sanctuary in a temple.[17]

With the ephors vanquished, Cleomenes initiated his reforms. First, he handed over his land to the state; he was soon followed by his stepfather and his friends, and then by the rest of the citizens. He divided up all of the Spartan land, awarding an equal lot to each citizen. He increased the citizen population by granting citizenship to some perioeci, who constituted the Spartan middle class, but did not at that time have Spartan citizenship. Expanding the citizen population meant that Cleomenes could build a larger army; he trained 4,000 hoplites and restored the old Spartan social and military discipline. He also strengthened his army by introducing the Macedonian sarissa (pike). Cleomenes completed his reforms by placing his brother, Eucleidas, in charge, making him the first Agiad king on the Eurypontid throne.[18]

Domination of the Peloponnese

Ptolemy III of Egypt offered continued assistance to Cleomenes on the condition that the Spartan king would offer his mother and children as hostages. Cleomenes hesitated but his mother, after learning of Ptolemy's offer, went voluntarily to Egypt.[19]

In 226 BC, the citizens of Mantinea appealed to Cleomenes to expel the Achaeans from the city. One night, he and his troops crept into the citadel and removed the Achaean garrison before marching off to nearby Tegea. From Tegea, the Spartans advanced into Achaea, where Cleomenes hoped to force the League to face him in a pitched battle. Cleomenes advanced with his army to Dyme, where he was met by the entire Achaean army. In the Battle of Dyme, the Spartans routed the Achaean phalanx, killing many of the Achaeans and capturing others. Following this victory, Cleomenes captured the city of Lasium and presented it to the Elians.[20]

The Achaeans were demoralized by this battle; Aratus declined the generalship, and when both Athens and the Aetolian League turned down their appeals, they sued Cleomenes for peace.[21] Initially, Cleomenes advanced only minor requests, but as the talks continued, his demands became greater and he eventually insisted that leadership of the League be surrendered to him. In exchange, he would return to the Achaeans the prisoners and strongholds he had seized. The Achaeans invited Cleomenes to Lerna, where they were holding council. While marching there, Cleomenes drank too much water, which caused him to lose his voice and cough up blood—a situation that forced him to return to Sparta.[22]

Aratus took advantage of this incident, and began plotting against Cleomenes with King Antigonus III Doson of Macedon. Previously, in 227 BC, two ambassadors from Megalopolis had been sent to Macedon to request help. Antigonus showed little interest at the time, and these efforts failed.[23] Aratus wanted the Macedonian king to come to the Peloponnese and defeat Cleomenes, but Antigonus asked for control of Acrocorinth in return.[24] This was a sacrifice that the League was not willing to make, however, and they declined to seek help from Macedon.[25][Note 2]

When the Achaeans arrived at Argos for an assembly, Cleomenes came down from Tegea to meet them. However, Aratus—who had reached an agreement with Antigonus—demanded that Cleomenes present 300 hostages to the Achaeans and enter the city alone, or approach the city with all his forces. When this message reached Cleomenes, he declared that he had been wronged and once again declared war on the Achaeans.[27]

Achaea was now in turmoil, and some cities were close to revolt; many residents were angered at Aratus' decision to invite the Macedonians into the Peloponnese. Some also hoped that Cleomenes would introduce constitutional changes in their cities. Encouraged by this development, Cleomenes invaded Achaea and seized the cities of Pellene, Pheneus, and Penteleium, effectively splitting the Achaean League in half.[28] The Achaeans, concerned about developing treachery in Corinth and Sicyon, dispatched their mercenaries to garrison the cities and then went to Argos to celebrate the Nemean Games.[27]

Cleomenes estimated that Argos would be easier to capture while filled with festival-goers and spectators to cause panic. During the night, he seized the rugged area above the city's theatre. The people of the city were too terrified to offer resistance. They accepted a garrison, delivered twenty hostages to Cleomenes and became Spartan allies.[29] The capture of Argos gave Cleomenes' reputation a massive boost, since no Spartan king had ever managed to seize Argos. Even Pyrrhus of Epirus, one of the most famous generals of the age, had been killed while trying to take the city.[30]

Soon after the seizure of Argos, Cleonae and Phlius surrendered themselves to Cleomenes. Meanwhile, Aratus was in Corinth investigating those suspected of supporting Sparta. When he heard what had happened at Argos, Aratus expected the city to fall to Sparta. He summoned an assembly and, with all the citizens present, he took his horse and fled to Sicyon. The Corinthians did surrender the city to Cleomenes, but the Spartan king criticized them for failing to arrest Aratus. Cleomenes sent his stepfather Megistonous to Aratus, asking for the surrender of Acrocorinth—the citadel of Corinth, which had an Achaean garrison—in return for a large amount of money.[31]

In quick succession, Hermione, Troezen, and Epidaurus surrendered to Cleomenes, who went from Argos to Corinth and started besieging the citadel.[28] He sent a messenger to Aratus proposing that Acrocorinth should be garrisoned jointly by both the Spartans and the Achaeans, and that he would deliver a twelve talent pension. Aratus faced the hard decision of whether to give the city to Antigonus or to let it fall to Cleomenes. He chose to conclude an alliance with Antigonus and sent his son as a hostage to Macedon. Cleomenes invaded the territory of Sicyon and blockaded Aratus inside the city for three months before Aratus was able to escape to attend the Achaean council at Aegium.[32]

Macedonian intervention

Antigonus, who had brought with him a large force of 20,000 infantry and 1,300 cavalry, was marching through Euboea towards the Peloponnese.[33] The hostile Aetolian League occupying parts of Thessaly had threatened to oppose him if he went further south than Thermopylae, despite their neutrality at that point in the war.[34] Aratus met Antigonus at Pagae, where he was pressured by Antigonus into giving Megara to Boeotia. When Cleomenes heard of the Macedonian advance through Euboea, he abandoned his siege of Sicyon and constructed a trench and palisade running from Acrocorinth to the Isthmus. He chose this location to avoid facing the Macedonian phalanx head-on.[35]

Despite numerous attempts to break through the defensive line and reach Lechaeum, Antigonus' force failed and suffered considerable losses.[36] These defeats took such a toll on Antigonus that he considered abandoning his attack on the palisade and moving his army to Sicyon. However, Aratus was visited one evening by some friends from Argos who invited Antigonus to come to their city. The Argives were ready to revolt under the command of Aristoteles, as they were irritated that Cleomenes had not made any reforms in the city. Antigonus sent 1,500 men under the command of Aratus to sail to Epidaurus and, from there, march to Argos. At the same time the Achaean strategos for the year, Timoxenos, advanced with more men from Sicyon. When the Achaean reinforcements arrived, the entire city except for the citadel was in the hands of the Argives.[37]

When Cleomenes heard about the revolt at Argos, he sent his stepfather with 2,000 men to try and save the situation. Megistonous was killed while assaulting the city, however, and the relief force retreated, leaving the Spartans in the citadel to continue resistance. Cleomenes abandoned his much stronger position at the Isthmus for fear of being encircled and left Corinth to fall into the hands of Antigonus. Cleomenes advanced his troops upon Argos and forced his way into the city, rescuing the men stuck in the citadel. He retreated to Mantinea when he saw Antigonus' army on the plain outside the city.[38]

After retreating into Arcadia and receiving news of his wife's death, Cleomenes returned to Sparta. This left Antigonus free to advance through Arcadia and on the towns that Cleomenes had fortified, including Athenaeum—which he gave to Megalopolis. He continued to Aegium, where the Achaeans were holding their council. He gave a report on his operations and was made chief-in-command of all the allied forces.[39]

Antigonus took the opportunity to revive the Hellenic League of Philip II of Macedon, under the name League of Leagues. Most of the Greek city states took part in the league. These included Macedon, Achaea, Boeotia, Thessaly, Phocis, Locris, Acarnania, Euboea, and Epiros. Peter Green claims that for Antigonus, the League was just a way to further Macedon's power.[40]

In the early spring of 223 BC, Antigonus advanced upon Tegea. He was joined there by the Achaeans and together they laid siege to it. The Tegeans held out for a few days before being forced to surrender by the Macedonians' siege weapons. After the capture of Tegea, Antigonus advanced to Laconia, where he found Cleomenes' army waiting for him. When his scouts brought news that the garrison of Orchomenus was marching to meet Cleomenes, however, Antigonus broke camp and ordered a forced march; this caught the city by surprise and forced it to surrender. Antigonus proceeded to capture Mantinea, Heraea, and Telphusa, which confined Cleomenes to Laconia. Antigonus then returned to Aegium, where he gave another report about his operations before dismissing the Macedonian troops to winter at home.[41]

Knowing that Cleomenes got the money to pay for his mercenaries from Ptolemy, Antigonus, according to Peter Green, seems to have ceded some territory in Asia Minor to Ptolemy in return for Ptolemy withdrawing his financial support of Sparta. Whether this assumption is accurate or not, Ptolemy certainly withdrew his support, which left Cleomenes without money to pay for his mercenaries. Desperate, Cleomenes freed all helots able to pay five Attic minae; in this way he accumulated 500 talents of silver. He also armed 2,000 of the ex-helots in Macedonian style to counter the White Shields, the Macedonian crack troops, before planning a major initiative.[42]

Fall of Megalopolis

Cleomenes noted that Antigonus had dismissed his Macedonian troops and only traveled with his mercenaries. At the time Antigonus was in Aegium, a three-day march from Megalopolis. Most of the Achaeans of military age had been killed at Mount Lycaeum and Ladoceia. Cleomenes ordered his army to take five days' worth of rations and sent his troops toward Sellasia, to give the appearance of raiding the territory of Argos. From there he went to the territory of Megalopolis; during the night he ordered one of his friends, Panteus, to capture the weakest section of the walls, while Cleomenes and the rest of the army followed. Panteus managed to capture that section of the wall after killing the sentries. This allowed Cleomenes and the rest of the Spartan army to enter the city.[43]

When dawn came, the Megalopolitans realised that the Spartans had entered the city; some of them fled, while others stood and fought against the invaders. Cleomenes' superior numbers forced the defenders to retreat, but their rearguard action allowed most of the population to escape—only 1,000 were captured. Cleomenes sent a message to Messene, where the exiles had gathered, offering to give back their city if they became his allies. The Megalopolitans refused; in retaliation the Spartans ransacked the city and burnt it to the ground. Nicholas Hammond estimated that Cleomenes managed to accumulate around 300 talents of loot from the city.[44]

Battle of Sellasia

The destruction of Megalopolis shook the Achaean League. Cleomenes set off with his army to raid the territory of Argos, knowing that Antigonus would not resist him due to a lack of men. Cleomenes also hoped that his raid would cause the Argives to lose confidence in Antigonus because of his failure to protect their territory.[45] Walbank describes this raid as being "an impressive demonstration, but it had no effect other than to make it even more clear that Cleomenes had to be defeated in a pitched battle."[46]

In the summer of 222 BC, Antigonus summoned his troops from Macedon, who arrived together with other allied forces. According to Polybius, the Macedonian army consisted of 10,000 Macedonian infantry, most of them armed as phalangites, 3,000 peltasts, 1,200 cavalry, 3,000 mercenaries, 8,600 Greek allies, and 3,000 Achaean infantry, making a total of 29,200 men.[47]

Cleomenes had fortified all the passes into Laconia with barricades and trenches before setting off with his army of 20,000 men to the pass at Sellasia, on the northern border of Laconia. Overlooking the pass at Sellasia were two hills, Evas and Olympus. Cleomenes positioned his brother, Eucleidas, with the allied troops and the Perioeci on Evas; he stationed himself on Olympus with 6,000 Spartan hoplites and 5,000 mercenaries.[47]

When Antigonus reached Sellasia with his army, he found it well guarded and decided against storming the strong position. Instead he pitched camp near Sellasia and waited for several days. During this time, he sent scouts to reconnoiter the areas and feign attacks on Cleomenes' position.[49]

Unable to force a move from Cleomenes, Antigonus decided to risk a pitched battle. He positioned some of his Macedonian infantry and Illyrians facing the Evas hill in an articulated phalanx. The Epirots, the Acarnanians and 2,000 Achaean infantry stood behind them as reinforcements. The cavalry took a position opposite Cleomenes' cavalry, with 1,000 Achaean and Megalopolitan infantry in reserve. Together with the rest of his Macedonian infantry and mercenaries Antigonus took his position opposite that of Cleomenes.[50]

The battle started when the Illyrian troops on the Macedonian right wing attacked the Spartan force on Evas. The Spartan light infantry and cavalry, noticing that the Achaean infantry was not protected at the rear, launched an assault on the back of the Macedonian right wing, and threatened to rout it.[51] However, at the critical moment, Philopoemon of Megalopolis (who later became one of the greatest heroes of the Achaean League, eventually conquering Sparta), tried to point out the danger to the senior cavalry commanders. When they did not take notice of him, Philopoemon gathered a few other cavalrymen and charged the Spartan cavalry. The Spartans attacking from the rear broke off their engagement with the enemy, which encouraged the Macedonians to charge at the Spartan positions. The Spartans' left flank was eventually forced back and thrown from their position and their commander, Eucleidas, killed;[46] they fled the field.[52]

Meanwhile, the Macedonian phalanx on the left flank engaged the Spartan phalanx and mercenaries. During the initial assault, the Macedonian phalanx gave a considerable amount of ground before its weight drove back the Spartan phalanx. The Spartans, overwhelmed by the deeper ranks of Macedonian phalanx, were routed, but Cleomenes managed to escape with a small group of men. The battle was very costly for the Spartans; only 200 of the 6,000 Spartans that fought survived the battle.[53]

Aftermath

Following his defeat at Sellasia, Cleomenes briefly returned to Sparta and urged the citizens to accept Antigonus' terms. Under cover of darkness, he fled from Sparta with some friends and went to the city's port of Gythium, where he boarded a ship heading to Egypt.[54]

Antigonus entered Sparta triumphantly, its first foreign conqueror. Nevertheless, he treated the population generously and humanely. He ordered that the reforms of Cleomenes be revoked, and restored the ephors, although he did not force Sparta to join the League. However, Antigonus' failure to restore the Spartan kings suggests to historian Graham Shipley that this restoration of laws was a sham.[55] Within three days, he left Sparta and returned to Macedon to deal with a Dardani invasion, leaving a garrison in Acrocorinth and Orchomenos. With Cleomenes' defeat, Sparta's power collapsed and it fell into the hands of successive tyrants.[56]

On his arrival at Alexandria, Cleomenes was greeted by Ptolemy, who welcomed him with smiles and promises. At first Ptolemy was guarded towards Cleomenes, but soon came to respect him and promised to send him back to Greece with an army and a fleet. He also promised to provide Cleomenes with an annual income of twenty-four talents.[57] However, before he could fulfill his promise, Ptolemy died—and with him any hope for Cleomenes to return to Greece, as the weak Ptolemy IV ascended the throne.[58]

Ptolemy IV began treating Cleomenes with neglect and soon his chief minister, Sosibius, had Cleomenes put under house arrest after he was falsely accused of plotting against the king.[59] In 219 BC, Cleomenes and his friends escaped from house arrest and ran through the streets of Alexandria, trying to encourage an uprising against Ptolemy. When this failed, Cleomenes and all of his friends committed suicide.[60]

Notes

- ↑ According to Plutarch, the position of the ephors was introduced to Sparta in 700 BC by King Theopompus. The ephors were five men who were elected annually by the Spartan assembly and after they held the post once they could not do so again.[6] The ephors looked after the day-to-day running of the state and were the arbiters of war and peace. The position was created to check and restrain the power of the king.[7] In the Achaean League, the position of strategos was the highest. A strategos was elected annually by the Achaean ekklesia or assembly and he was the lead general of the League for the year, as well as the chief magistrate. No one could hold the position for more than one year.[8]

- ↑ The Danish historian Barthold Georg Niebuhr criticizes Aratus' alliance with Macedon, arguing that "old Aratus sacrificed the freedom of his country by an act of high treason, and gave up Corinth rather than establish the freedom of Greece by a union among the Peloponnesians, which would have secured to Cleomenes the influence and power he deserved."[26]

Citations

- ↑ Hammond & Walbank 2001, p. 305.

- ↑ Habicht 1997, p. 175; Hammond & Walbank 2001, p. 353.

- ↑ Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire, 2.46.

- ↑ Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 3; Plutarch. Life of Agis, 20.

- 1 2 Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire, 2.46; Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 4; Hammond & Walbank 2001, p. 342.

- ↑ Plutarch. Plutarch on Sparta, 7.

- ↑ Lemprière 1904, p. 222.

- ↑ Avi-Yonah & Shatzman 1975, p. 434.

- ↑ Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 4; Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, "Cleomenes III".

- 1 2 Hammond & Walbank 2001, p. 342.

- 1 2 Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 4; Hammond & Walbank 2001, p. 342.

- ↑ Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire, 2.51; Green 1990, p. 249; Walbank 1984, p. 464; Hammond & Walbank 2001, p. 347.

- ↑ Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 5; Hammond & Walbank 2001, p. 345.

- ↑ Pausanias. Description of Greece, 2.9.1.

- ↑ Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire, 5.37; Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 5; Hammond & Walbank 2001, p. 345.

- ↑ Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 6; Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, "Cleomenes III".

- ↑ Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 7; Green 1990, p. 257; Hammond & Walbank 2001, p. 345.

- ↑ Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 11; Green 1990, p. 257; Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, "Cleomenes III".

- ↑ Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 22; Green 1990, p. 258.

- ↑ Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 14; Green 1990, p. 258; Hammond & Walbank 2001, p. 347.

- ↑ Habicht 1997, p. 185; Walbank 1984, p. 466.

- ↑ Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 15; Green 1990, p. 258; Hammond & Walbank 2001, p. 347.

- ↑ Grainger 1999, p. 252.

- ↑ Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 16.

- ↑ Green 1990, p. 258.

- ↑ Niebuhr, Barthold Georg. A History of Rome (Volume II), p. 146.

- 1 2 Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 17.

- 1 2 Walbank 1984, p. 465.

- ↑ Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 17; Green 1990, p. 259; Walbank 1984, p. 465.

- ↑ Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 18.

- ↑ Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 19; Green 1990, p. 259.

- ↑ Walbank 1984, p. 465; Green 1990, p. 259.

- ↑ Walbank 1984, p. 466.

- ↑ Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire, 2.52; Grainger 1999, p. 252.

- ↑ Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire, 2.52; Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 20; Green 1990, p. 259.

- ↑ Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 20.

- ↑ Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 21; Walbank 1984, p. 21.

- ↑ Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire, 2.53; Plutarch. Cleomenes, 21; Walbank 1984, p. 467.

- ↑ Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire, 2.54; Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 22.

- ↑ Green 1990, p. 260; Habicht 1997, p. 178.

- ↑ Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire, 2.54; Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 23; Hammond & Walbank 2001, p. 353.

- ↑ Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 23; Green 1990, p. 260.

- ↑ Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 23; Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire, 2.55.

- ↑ Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire, 2.55; Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 24; Walbank 1984, p. 471; Hammond 1989, p. 326.

- ↑ Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire, 2.64; Walbank 1984, p. 471.

- 1 2 Walbank 1984, p. 471.

- 1 2 Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire, 2.65; Walbank 1984, p. 471.

- ↑ Warry 2000, p. 67.

- ↑ Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire, 2.66.

- ↑ Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire, 2.66; Hackett 1989, p. 133.

- ↑ Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire, 2.67.

- ↑ Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire, 2.69.

- ↑ Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire, 2.69; Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 28; Hammond 1989, p. 326; Walbank 1984, p. 472.

- ↑ Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire, 2.69; Plutarch. Cleomenes, 29; Walbank 1984, p. 472; Green 1990, p. 261.

- ↑ Shipley 2000, p. 146.

- ↑ Polybius. The Rise of the Roman Empire, 2.70; Plutarch, Life of Cleomenes, 30; Walbank 1984, p. 472; Green 1990, p. 261; Habicht 1997, p. 187.

- ↑ Plutarch, Life of Cleomenes, 32.

- ↑ Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 33; Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, "Cleomenes III"; Green 1990, p. 261.

- ↑ Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 34.

- ↑ Plutarch. Life of Cleomenes, 37; Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, "Cleomenes III"; Green 1990, p. 261; Walbank 1984, p. 476.

References

Primary sources

- Pausanias; W. H. S. Jones (trans.) (1918). Description of Greece. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674993280.

- Plutarch; John Langhorne (trans.); William Langhorne (trans.) (1770). "Life of Aratus". Plutarch's Lives. London, United Kingdom: Edward and Charles Dilly.

- Plutarch; Richard Talbert (trans.) (1988). "The Lives of Agis and Cleomenes". Plutarch on Sparta. New York, New York: Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044463-7.

- Polybius; Frank W. Walbank (trans.) (1979). The Rise of the Roman Empire. New York, New York: Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044362-2.

Secondary sources

- Avi-Yonah, Michael; Shatzman, Israel (1975). Illustrated Encyclopaedia of the Classical World. New York, New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-010178-4.

- Grainger, John D. (1999). The League of Aitolians. Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill. ISBN 90-04-10911-0.

- Green, Peter (1990). Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age. Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08349-0.

- Habicht, Christian (1997). Athens from Alexander to Antony. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-05111-4.

- Hackett, John Winthrop (1989). Warfare in the Ancient World. London, United Kingdom: Sidgwick & Jackson. ISBN 0-283-99591-2.

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (1989). The Macedonian State: Origins, Institutions and History. Oxford, United Kingdom: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-814883-6.

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière; Walbank, Frank William (2001). A History of Macedonia Volume III: 336–167 B.C. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-814815-1.

- Lemprière, John (1904). A classical dictionary, containing a copious account of all the proper names mentioned in ancient authors; with the values of coins, weights and measures used among the Greeks and Romans; and a chronological table. London: George Routledge & Sons.

- Niebuhr, Barthold Georg (1875). A History of Rome (Volume II). Million Book Project.

- Shipley, Graham (2000). The Greek World After Alexander: 323–30 BC. London, United Kingdom: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-04618-1.

- Smith, William (1873). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. London, United Kingdom: John Murray.

- Warry, John (1995). Warfare in the Classical World: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of Weapons, Warriors, and Warfare in the Ancient Civilisations of Greece and Rome. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2794-5.

- Walbank, Frank William (1984). The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 7, Part 1: The Hellenistic World. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23445-X.

- Warry, John Gibson (2000). Warfare in the Classical World. Barnes & Noble Publishing. ISBN 0-7607-1696-X.