The Clemson–South Carolina rivalry is an American collegiate athletic rivalry between the Clemson University Tigers and the University of South Carolina Gamecocks, the two largest universities in the state of South Carolina. Since 2015, the two compete in the Palmetto Series, which consists of more than a dozen athletic, head-to-head matchups each school year. The all-sport series has been won by South Carolina each year.[1][2][3][4] Both institutions are public universities supported by the state, and their campuses are separated by only 132 miles. South Carolina and Clemson have been bitter rivals since 1896, and a heated rivalry continues to this day for a variety of reasons, including the historic tensions regarding their respective charters and the passions surrounding their athletic programs. It has often been listed as one of the best rivalries in college sports.[5][6][7][8][9]

Much like the Alabama–Auburn rivalry, the Clemson–Carolina rivalry is an in-state collegiate rivalry. However, unlike Alabama–Auburn, this is one of a handful of rivalries where the teams are in different premier conferences: South Carolina is in the Southeastern Conference (SEC); Clemson is in the Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC).[10][11]

The annual football game is considered the most important sporting event in the state.[12] It was played first in 1896 and every year from 1909 to 2019, one of the longest uninterrupted rivalries in college football history.[13][14][15] Until 1959, the game was played during the State Fair in Columbia, on "Big Thursday", a state holiday.[16] Since 1960, the two schools have alternated hosting on Saturdays. In 2014, the annual football game was officially dubbed the Palmetto Bowl.[17] Due to the global COVID-19 pandemic, the 2020 meeting of the two football teams was cancelled, ending an unbroken streak of 111 years of games.[18] The game has never been contested anywhere besides Columbia or Clemson. Clemson leads the series 73–43–4,[19] and won the most recent game with a score of 16–7.[20]

Origin

Background

| Clemson | South Carolina | |

|---|---|---|

| Founded | 1889 | 1801 |

| Location | Clemson, SC | Columbia, SC |

| Conference | ACC | SEC |

| Students | 24,951 | 34,795 |

| School colors | ||

| Nickname | Tigers | Gamecocks |

| Mascot | The Tiger | Cocky |

Unlike most major college rivalries, the Carolina–Clemson rivalry did not start innocently or because of competitive collegiate sports. The deep-seated bitterness began between the two schools long before Clemson received its charter and became a college. The two institutions were founded eighty-eight years apart: South Carolina College in 1801 and Clemson Agricultural College in 1889.

South Carolina College was founded in 1801 to unite and promote harmony between the Lowcountry and the Backcountry.[21] It closed during the Civil War when its students aided the Southern cause, but the closure gave politicians an opportunity to reorganize it to their liking.[22][23] The Radical Republicans in charge of state government during Reconstruction opened the school to blacks and women while appropriating generous funds to the university, which caused the white citizens of the state to withdraw their support for the university[24] and view it as a symbol of the worst aspects of Reconstruction.

The Democrats returned to power in 1877 following their electoral victory over the Radical Republicans and promptly proceeded to close the university. Sentiment in the state favored opening an agriculture college, so the university was reorganized as the South Carolina College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts.[25] In 1882, the college was renamed to its antebellum name, South Carolina College, which infuriated the farmers who felt that the politicians had frustrated the will of the people by de-emphasizing agriculture education, even though the school still retained the department of agriculture.[26] Clemson, from its beginning, was an all-white male military school. The school remained this way until 1955 when it changed to "civilian" status for students and became a coeducational institution.[27]

Agitation from the farmers

Benjamin Tillman emerged in the 1880s as a leader of the agrarian movement in South Carolina and demanded that the South Carolina College take agricultural education more seriously by expanding the agriculture department.[28] In 1885, Tillman was convinced of the superiority of a separate agricultural college by Stephen D. Lee, then the president of the Agricultural and Mechanical College of the State of Mississippi, and subsequently Tillman would accept nothing less than a separate agriculture college in South Carolina.[29] He offered the following reasons why he felt that it was necessary to have a separate agriculture college outside the confines of Columbia:

- Mississippi A&M featured practical training without unnecessary studying of the liberal arts.[29]

- Mississippi A&M provided poor students work-scholarships so that they could attend the college.[29]

- There were too few students who studied agriculture at the college to justify an agriculture college there.[29]

- The college was a place "for the sons of lawyers and of the well-to-do"[30] who sneered at the agriculture students as if they were hayseeds.[31]

- The students at the college lived a life of luxury as compared with the sweat and toil endured by students at Mississippi A&M.[32]

- There was not enough farm land near the college to allow for proper agriculture study.[33]

The Conservatives, who held the reins of power in South Carolina from 1877 to 1890, replied to each point made by Tillman:

- The most advanced agriculture educational research was being conducted at the University of California and at Cornell University, both of which combined agriculture colleges with liberal arts colleges.[34] Additionally, a separate agriculture college would be more expensive and result in an inferior product.[35]

- The work scholarships attracted the lowest quality of students who only cared about obtaining a college degree, not about an education in agriculture or mechanical studies. Furthermore, there was little advantage of attending a college only to pitch manure and grub stumps.[36]

- The constant attacks by Tillman on the college caused many to doubt whether state support for the institution would continue. As a result, the enrollment numbers were not impressive, although the numbers of students taking agriculture and mechanical classes increased from 34 in 1887 to 83 in 1889.[37]

- Over half of the students at the college were the sons of farmers, though most did not study agriculture as Tillman wished.[31] John McLaren McBryde, President of the college, correctly predicted that most students of an agriculture college would not go back to work the farm after graduation.[31]

- While some students at the college were the sons of the well-to-do, the majority were poor.[32]

- The college farm added 100 acres (0.4 km2) in 1887, just one mile from campus.[38]

Clemson's will

Tillman was bolstered in 1886 when Thomas Green Clemson agreed to will his Fort Hill estate for the establishment of an agriculture college.[39] Yet, Tillman did not want to wait until Clemson died to start a separate agriculture college so he pushed the General Assembly to use the Morrill funds and Hatch funds for that purpose.[40] Instead, the legislature gave those funds to the South Carolina College in 1887 which would use them along with a greater state appropriation to reorganize itself as the second University of South Carolina and additionally, to expand the agriculture department greatly.[41] After this victory for South Carolina, in January 1888 Tillman wrote a letter to the News and Courier that he was retiring from public life.[42][43]

| Tillmanites | Conservatives | |

| Favored college | Clemson | South Carolina |

| Figurehead leader | Benjamin Tillman | Wade Hampton III |

| Political ideology | Agrarian populism | Conservatism |

| Base of support | The Upstate; rural | Statewide; urban |

| Confederate service | 50.0%[44] | 79.1%[44] |

It was less than ninety days when Tillman reemerged on the scene upon the death of Thomas Green Clemson in April 1888.[45] Tillman advocated that the state accept the gift by Clemson, but the Conservatives in power opposed the move and an all out war for power in the state commenced. The opening salvo was fired by Gideon Lee, the father of Clemson's granddaughter and John C. Calhoun's great-granddaughter Floride Isabella Lee, who wrote a letter on her behalf to the News and Courier in May that she was being denied as Calhoun's rightful heir.[46] Furthermore, he stated that Clemson was egotistical and "only wanted to erect a monument to his own name."[46] In November, Lee filed a lawsuit in Federal Court to contest the will which ultimately ruled against him in May 1889.

The election of 1888 afforded Tillman an opportunity to convince the politicians to accept the Clemson bequest or face the possibility of being voted out of office. He demanded that the Democratic party nominate its candidates by the primary system, which was denied, but they did accept his request that the candidates for statewide office canvass the state.[47] Tillman proved excellent on the stump, by far superior to his Conservative opponents, and as the Democratic convention neared there was a clear groundswell of support for the acceptance of Clemson's estate.[48]

Clemson's Bequest barely wins support

Tillman explained his justification for an independently controlled agriculture college by pointing to the mismanagement and political interference of the University of South Carolina as had occurred during Reconstruction. The agriculture college, as specified in Clemson's will, was to be privately controlled. With declining cotton prices, Tillman played upon the farmer's desperation by stating that the salaries of the college professors were exorbitant and it must be a sign of corruption.[49] Consequently, the legislature was compelled to pass the bill to accept Clemson's bequest in December 1888, albeit with the tie-breaking vote in the state Senate from Lieutenant Governor William L. Mauldin.[46] Thus was reborn the antagonistic feelings of regional bitterness and class division that would plague the state for decades.[50]

Having achieved his agriculture college, Tillman was not content to sit idly by because what he really desired was power and political office.[51] After winning the 1890 election and becoming governor, Tillman renewed the attacks on the Conservatives and those who had thwarted his agriculture college. He saved the coup de grâce for Senator Wade Hampton III, a South Carolina College graduate and Confederate General during the Civil War, who "invoked Confederate service and honor as a barrier to Tillmanism."[52] Tillman directed the legislature to defeat Hampton's renomination for another term in December 1890.[52][53]

While campaigning for governor in 1890, Tillman leveled his harshest criticism towards the University of South Carolina and threatened to close it along with The Citadel, which he called a "dude factory."[54] Despite the rhetoric, Tillman only succeeded in reorganizing the University of South Carolina into a liberal arts college while in office.[55] It would eventually be rechartered for the last time in 1906 as the University of South Carolina. However, Clemson Agricultural College held sway over the state legislature for decades and was generally the more popular college during the first half of the 20th century in South Carolina.[56]

Growth Battle

In the 1950s, the University of South Carolina expanded its reach across the state by establishing branch campuses under the auspices of the University of South Carolina System.[57] Clemson, having obtained university status in 1964, established a branch campus in Sumter and formed a two-year transfer partnership with Greenville Technical College.[58] House Speaker Sol Blatt was alarmed by the spread of Clemson and declared that South Carolina "should build as many two-year colleges over the state as rapidly as possible to prevent the expansion of Clemson schools for the Clemson people."[59] Accordingly, the University of South Carolina began a new wave of expansion across the state and was aided by the fact that the Clemson Sumter extension suffered from low enrollment. In 1973, Sumter officials negotiated an agreement between USC and Clemson for the school to join the USC branch system.[60]

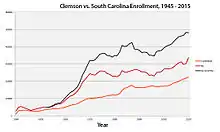

In the past ten years, Clemson has experienced a larger percentage of enrollment growth over its rival school. Since 2005, Clemson University has grown by 30.5 percent[61] compared to USC's 24.5 percent growth at its main Columbia campus and a 22.5 percent enrollment increase in the entire USC system.[62] Both schools currently enroll more students than any time in their entire history.

Football

| First meeting | November 12, 1896 South Carolina, 12–6 |

|---|---|

| Latest meeting | November 25, 2023 Clemson, 16–7 |

| Next meeting | November 30, 2024 |

| Trophy | Hardee's Trophy (1980s–2014) Palmetto Trophy (2015–present) [63] |

| Statistics | |

| Meetings total | 120 |

| All-time series | Clemson leads, 73–43–4[64] |

| Largest victory | Clemson, 51–0 (1900) |

| Longest win streak | Clemson, 7 (1934–40 & 2014–2021) |

| Current win streak | Clemson, 1 (2023–present) |

The annual Clemson–South Carolina football game (sometimes dubbed "The Battle of the Palmetto State" and unofficially called the "Palmetto Bowl" beginning in the 1950s, known officially since 2014 as the "Palmetto Bowl", from the state's nickname) was the longest uninterrupted series in the South and the second longest uninterrupted NCAA DI-A/FBS series in the country. The streak came to an end in 2020 as the SEC announced their member teams would not play out of conference games due to the COVID-19 pandemic, thus cancelling the matchup vs. Clemson.[18] The series dates back to 1896, and had been renewed every year since 1909 (111 consecutive games).[65] The universities maintain college football stadiums in excess of 80,000 seats each, placing both in the top 20 in the United States.[66] Although the series has been interrupted seven times since its inception, it ran uninterrupted from 1909 to 2019, making it the second-longest continuous rivalry in FBS Division 1 college football, after only Minnesota/Wisconsin (uninterrupted since 1907). From 1896 to 1959, the Clemson–South Carolina game was played in Columbia and referred to as "Big Thursday".[67] Since 1960, the game has alternated between both teams' home stadiums—South Carolina's Williams-Brice Stadium and Clemson's Memorial Stadium, usually as the regular season finale. Since 1962, the annual football game has been held in late November, usually on Thanksgiving weekend. Games in odd-numbered years are played in Columbia at South Carolina, and even-numbered years in Clemson at Clemson University.

Clemson holds a 73-43–4 lead in the series. Clemson holds a 44–30–2 advantage in the Modern Era (post-WWII), and Clemson leads the series 14–8 in the 21st century. Clemson's 73 wins against South Carolina is more than any other program has,[68] and Carolina's 43 wins against Clemson is tied with Georgia for second behind Georgia Tech's 50 wins.[69]

Every year, each school engages in a ritual involving the other team's mascot. South Carolina holds the "Tiger Burn", and Clemson holds a mock funeral for Cocky. After seven students—six from South Carolina and one from Clemson—died in the Ocean Isle Beach house fire in 2007, the Cocky funeral was cancelled and the Tiger Burn was changed to the "Tiger Tear Down" for that year.[70][71][72]

Early years: 1896–1902

When Clemson began its football program in 1896, coached by Walter Riggs, they scheduled the rival South Carolina College for a Thursday morning game in conjunction with the State Fair. Carolina won that game 12–6 and a new tradition was born – Big Thursday. Clemson would win the next four contests (including a 51–0 win in 1900, still the largest margin of victory by either team in the series) before the 1st break in the series took place in 1901.

The Gamecock mascot made its first appearance in 1902. In that first season as the Gamecocks, Carolina defeated a highly favored Clemson team coached by the legendary John Heisman 12–6. But it was the full-scale riot that broke out in the wake of the game that is remembered most.

"The Carolina fans that week were carrying around a poster with the image of a tiger with a gamecock standing on top of it, holding the tiger's tail as if he was steering the tiger by the tail," Jay McCormick said. "Naturally, the Clemson guys didn't take too kindly to that, and on Wednesday and again on Thursday, there were sporadic fistfights involving brass knuckles and other objects and so forth, some of which resulted, according to the newspapers, in blood being spilled and persons having to seek medical assistance. After the game on Thursday, the Clemson guys frankly told the Carolina students that if you bring this poster, which is insulting to us, to the big parade on Friday, you're going to be in trouble. And naturally, of course, the Carolina students brought the poster to the parade. If you give someone an ultimatum and they are your rival, they're going to do exactly what you told them not to do."[73]

As expected, another brawl broke out before both sides agreed to mutually burn the poster in an effort to defuse tensions. The immediate aftermath resulted in the stoppage of the rivalry until 1909.

.png.webp)

World War II era

World War II produced one of the most bizarre situations in the history of the rivalry. Cary Cox, a football player of the victorious Clemson squad in 1942, signed up for the V-12 program in 1943 and was placed at USC. The naval instructors at USC ordered him to play on the football team and he was named the captain for the Big Thursday game against Clemson. Cox was reluctant to play against his former teammates and he voiced his concerns to coach Lt. James P. Moran who responded, "Cox, I can't promise you'll get a Navy commission if you play Thursday, but I can damn well promise that you won't get one if you don't play."[74] Cox then went out and led the Carolina team to a 33–6 win against Clemson. He returned to Clemson after the war and captained the 1947 team in a losing effort to Carolina, but Cox earned his place in history as the only player to captain both schools' football teams.

Modern era – Post World War II

1946: Near riot – counterfeit tickets

The 1946 game could be the most chaotic in the football series. Two New York mobsters printed counterfeit tickets for the game. Fans from both sides were denied entrance when the duplicate tickets were discovered, which led to a near riot. To add to the wild scene, a Clemson fan strangled a live chicken at midfield during halftime. Fans from both sides of the rivalry, many of whom who had been denied entrance, along with fans who poured out of the stands, stormed the fences and gates and spilled onto the field. It took U.S. Secretary of State James F. Byrnes, who attended the game along with then-Governor-elect Strom Thurmond, to settle down the hostile crowd. Once order was restored, fans were allowed to stand along the sidelines, with the teams, while the second half was played to the game's conclusion. The Gamecocks eventually won by a score of 26–14.[75]

1952: Game mandated by South Carolina law

The Southern Conference (SoCon) almost brought the longstanding rivalry to an abrupt end when it ordered Clemson to play no other league team other than Maryland as punishment for both schools accepting bowl bids against conference rules (both Clemson and USC were members at the time). Upon request of both schools' presidents, the S.C. General Assembly passed a resolution on February 27, 1952, ordering the game to be played.[76] The Gamecocks won the contest 6–0. The SoCon reacted to the game by attempting to suspend Clemson, leading seven member schools, including Clemson and USC, to leave the league and form the Atlantic Coast Conference in May 1953.[77]

1959: Final Big Thursday

For 64 years, Clemson traveled to Columbia to face the Gamecocks for the annual Big Thursday rivalry. This year would mark the end of the tradition as the rivalry progressed to a home-and-home series played on a Saturday. However, the two schools would not move the contest to the last regular season game until two years later. Clemson won the final Big Thursday match-up 27–0.[78]

1960: First game played in Clemson and on Saturday, state and town records broken

On November 12, 1960, Clemson played South Carolina at home for the first time in history. Additionally, the game was played on a day other than Thursday (Saturday) for the first time ever. It was reportedly "the largest crowd to see an athletic event" in the state and "the greatest number of automobiles ever driven" to Clemson, until then. In what was called a "defensive duel" in front of a record crowd of 45,000, Clemson won the matchup 12–2.[79] From here on out, the two schools would continue to alternate hosting the game.

1961: "The Prank"

In 1961, the USC fraternity Sigma Nu pulled what some have called "the greatest prank in rival history". A few minutes before Clemson football players entered the field for pre-game warm ups, a group of Sigma Nu fraternity members ran onto the field, jumping up and down and cheering in football uniforms that resembled the ones worn by the Tigers. This caused the Clemson band to start playing "Tiger Rag," which was followed by the pranksters falling down as they attempted to do calisthenics. They would also do football drills where guys would drop passes and miss the ball when trying to kick it. Clemson fans quickly realized that they had been tricked, and some of them angrily ran onto the field. However, security restored order before any blows could be exchanged. The Carolina frat boys had also acquired a sickly cow they planned to bring out during halftime to be the "Clemson Homecoming Queen", but the cow died en route to the stadium. Carolina won the game 21–14.

1963: Postponed due to national tragedy

On November 22, 1963, just over an hour after the Tigers’ buses departed for Columbia, President John F. Kennedy was assassinated. The team arrived in Batesburg for a practice, and received the news from the hotel staff. Both schools planned to proceed with the original day and time (the next day, November 23), which was going to be just the second regular-season game televised in Clemson history. However, as the evening continued, more and more schools across the shocked nation announced postponements or cancellations of their games. At 10:00 PM, Clemson and South Carolina released a joint statement, saying their game would be pushed back to November 28, Thanksgiving Day. Clemson won the game 24–20. However, it was not televised on CBS as originally planned.[80]

1971: First game with African-American players on both teams, no longer conference opponents, state record broken

In 1970, both football programs had at least one black player. However, Marion Reeves, Clemson's first black football player, was a freshman in 1970 and thus was not eligible to play in the rivalry game, or any game. In the 1971 rivalry game, Carlton Haywood and Jackie Brown were both starters for South Carolina, while Reeves (now an eligible player) came off the bench as a sophomore and recorded two interceptions. Thus, the 1971 Clemson–Carolina game was the first in the series in which black players played for both teams. Additionally, South Carolina left the ACC after the 1970 season, making the 1971 matchup the first in the series since 1921 to be a non-conference game, which it remains today. The game was played in front of a crowd of 57,242 at Carolina Stadium, reportedly "the largest ever to see a football game in South Carolina" until then. Clemson won 17–7.[81][82][83][84][85][86][87]

1975: Most points scored by Carolina

On November 22, 1975, Carolina defeated Clemson 56–20. This remains Carolina's largest margin of victory ever against the Tigers.[88]

1977: "The Catch"

In 1977, Clemson started the game 24–0, in Columbia. However, Carolina then scored the next 27 unanswered points to make it a 27–24 game, with 1:48 left in the fourth quarter. Carolina receiver Phil Logan even began revealing to the crowd a t-shirt which read “No Cigars Today" in reference to Clemson's new tradition of cigar celebrations that season. With 49 seconds left, Clemson WR Jerry Butler made a 20-yard touchdown reception on a pass from QB Steve Fuller to give Clemson the 31–27 victory. The official athletic site of the Clemson Tigers has described the reception as "a leaping, twisting catch that no one else could have made in that game, and no one else has made since". This play is known as "The Catch" and is seen as one of the most memorable plays in the rivalry.[89][90]

1980: Orange pants

In the last regular season game for the 1980 season, a heavily favored Carolina team traveled to Death Valley to take on the Tigers. In a surprise to both the players and the fans, Coach Danny Ford unveiled new orange uniform pants for the Tigers to wear. This was the first time in Clemson's history that they wore orange pants in any combination for a football game. Inspired by the pants, the underdog Tigers defeated the Gamecocks, 27–6.

1981: Clemson wins their first national championship

In 1981, Clemson defeated Carolina 29–13 en route to their first national championship.[91]

1984: Black magic

Carolina took their 9–1 record on the road to Clemson, and fell behind 21–3 to the Tigers. With about three minutes remaining in the game, Gamecock QB Mike Hold led an eight-play 86-yard touchdown drive and, thanks to a Clemson penalty that allowed a re-kick of a missed extra point, defeated the Tigers 22–21 to finish the first 10-win season in program history.[92]

1989: Orange on the road and Ford's last hurrah

After suffering two disappointing upsets to Duke and Georgia Tech, the 8–2 Tigers traveled to Columbia for the annual game. Danny Ford allowed the Clemson players to wear orange pants on the road for the first time. Led by halfback Terry Allen's 97-yard, two-touchdown first half, the Tigers rolled the Gamecocks on the ground for 355 yards en route to a 45–0 victory. The game would be Ford's last against South Carolina as Clemson's coach. He finished with a 7–3–1 record against the Gamecocks.[93][94][95]

1992: Signing the paw

After an 0–5 start to begin the 1992 season (USC's first in the SEC), freshman sensation Steve Taneyhill led Carolina to four wins in his first five starts as Gamecock quarterback. With Clemson needing a win at home to become bowl-eligible, Taneyhill led his team to a 24–13 victory and famously signed his name with his finger on the Tiger Paw at midfield following a key second-half touchdown.[96]

1994: "The return"

With both teams entering the game 5–5 and trying to become bowl-eligible, Carolina led 14–7 at the half in Clemson. Gamecock RB Brandon Bennett received the kick to start the third quarter, took a few steps, then turned and threw a backward pass to the other side of the field which was caught by DB Reggie Richardson who returned the ball 85 yards to the Tigers' 6-yard line. Bennett ran it in for a touchdown on the next play, putting Carolina ahead 21–7 and the Gamecocks never looked back, going on to win the game 33–7 and clinching a bid to the Carquest Bowl.[97]

2000: "The Catch II"/"The Push-off"

In 2000, for the first time since 1987, both teams were ranked entering the game. Trailing late in the game 14–13, Clemson quarterback Woody Dantzler connected with wide-receiver Rod Gardner for a 50-yard reception to Carolina's 8-yard line with ten seconds remaining. Carolina players and fans point to a replay that seems to show Gardner pushing off Gamecock defender Andre Goodman, while Clemson players and fans contend that the contact was mutual and incidental. No penalty flag was thrown on the play, leaving Clemson kicker Aaron Hunt to kick a 25-yard field goal that gave Clemson a 16–14 win. The game remains divisive, with Clemson fans remembering it as "The Catch II" and Carolina fans remembering it as "The Push-Off Game".[98]

2001: A bicentennial win

In the 200th year of the University of South Carolina, the Gamecocks hosted the Tigers at the end of a successful regular season that saw them ranked in the Top 25 every week and 7–3 heading into the rivalry game. Carolina jumped out to an early 20–9 lead behind a strong ground attack, and held on to win 20–15 and secure a bid to their second straight Outback Bowl. With the win, South Carolina reached eight wins in consecutive seasons for the first time since 1987-88. Because of the September 11 attacks, this was not the final regular season game for Clemson. The Tigers rescheduled their September 15 game (versus Duke) for the first weekend of December.[99][100]

2003: Most points scored by Clemson

In 2003, Clemson defeated Carolina 63–17 to set the record for the most points scored by either team in the series.

2004: "The Brawl"

In 2004, at home, the Tigers did their tradition of running down The Hill, where some Gamecocks waited for them at the bottom and began to shove and yell at them. The game continued on as normal until the fourth quarter when several South Carolina offensive linemen shoved a Clemson defensive end, beginning a brawl between both teams that lasted several minutes. Clemson won the game 29–7. Each team had won a total of six games that year, making them technically bowl eligible. However, both schools withdrew from bowl consideration because of the unsportsmanlike nature of the fight. Additionally, the SEC and ACC suspended six players from both South Carolina and Clemson for one game. This was also the last game ever coached by Hall of Famer Lou Holtz, having retired shortly thereafter.[101]

2005: A quarterback wins 4

In 2005, the two teams showed an unusual gesture of sportsmanship by meeting at midfield before the game to shake hands, putting the melee of 2004 behind them. Clemson won this game 13–9, leaving the Tigers' quarterback, Charlie Whitehurst, undefeated against USC in his 4 years at Clemson. The only Carolina quarterback to do so against the Tigers was Tommy Suggs, who led the Gamecocks to three victories in a row from 1968 to 1970.

2006: Kickers make the difference

Clemson was leading 28–14 in the third quarter, with Carolina quarterback Blake Mitchell throwing three interceptions. The Gamecocks then scored 17 unanswered points, including two Mike Davis touchdown runs and a 35-yard field goal from Ryan Succop – the only points in the fourth quarter – to give the Gamecocks a 31–28 lead. Clemson kicker Jad Dean missed a field goal attempt wide left as time expired to give Carolina the win. This game also marked the moving of the series to the Saturday following Thanksgiving Day.

2013: Highest-ranked meeting

In the highest-ever ranked matchup between the two teams (Clemson #6, South Carolina #10), the Gamecocks secured their fifth straight victory over the Tigers with a score of 31–17. Carolina took advantage of six turnovers by Clemson, including two during punt returns, to secure the victory. The win marked the Gamecocks' longest streak versus Clemson in the rivalry's history. With the win, South Carolina quarterback Connor Shaw finished his college career unbeaten at Williams-Brice Stadium.[102][103][104]

2020: Game canceled

Due to the COVID-19 outbreak, the SEC announced that no out-of-conference games would be played among its members, thus canceling the 2020 matchup between Clemson and South Carolina originally scheduled for November 28, 2020. The decision marked the first time the two teams would not play in over 100 years.[105]

2023: Latest meeting, President Trump in attendance

Both teams came in on a three-game winning streak for the first time since 2013.[106] Clemson's defense scored the game's first points on a scoop and score fumble on the Gamecocks' first play. Clemson held the Gamecocks to a total of 169 yards, and South Carolina's offense only crossed the 50 yard line twice. Clemson's kicker Jonathan Weitz added three field goals to cap off the 16–7 victory. This game was notably attended by 45th President of the United States Donald Trump during the lead up to the 2024 United States presidential election.[107]

Game results

| Clemson victories | South Carolina victories | Tie games |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Baseball

In baseball, Clemson leads the series overall 186–145–2. The teams previously met four times during the regular season, with two games scheduled at each home field. Two of the games were played on Saturday and Sunday, and then later in the season 2 games were played during the mid-week, usually on Wednesday. Since 2010, the teams have competed against each other over the course of a single weekend: once on each home field and once at a neutral site. Fluor Field at the West End (2010, 2011, 2013–2019) in Greenville, SC and Riley Park (2012) in Charleston, SC have served as the host sites. The other instances where the teams met in neutral site games were the 2002 College World Series and the 2010 College World Series, both times at Rosenblatt Stadium in Omaha, NE. Both schools are perennially considered to be among the top programs in the country, giving the rivalry a prominent spot in college baseball beyond the state of South Carolina. SEBaseball.com's Mark Etheridge has called it "college baseball's most heated rivalry,"[109] and Baseball America's Aaron Fitt has called it "far and away the most compelling rivalry college baseball has to offer."[110]

College World Series in the 21st Century

The rivalry has taken a deeper hold in the 2000s and 2010s, as twice in the century the two teams battled, coincidentally in the semifinals both times, with the Tigers being 2–0 and needing only one win to advance to the championship, and the Gamecocks losing the first game and having to win twice to reach the finals out of the double elimination repechage round in both situations.

2002

Leading up to the 2002 semifinals, Clemson had already won three out of four regular season games against Carolina. The Gamecocks beat their rivals soundly, 12–4, and then beat the Tigers again, 10–2, the following day to advance to the national championship game. The Gamecocks fell to Texas 12–6 in the championship game, the last under the format where a one-game final was played.[111]

2010

Eight years later, in what has been called The Last Bat at Rosenblatt, an identical situation leading to the series began. Clemson had taken both on-campus games from South Carolina in the regular season, including a lopsided 19–6 victory in the rubber match, played before over 8,000 fans at Carolina Stadium in Columbia, but had lost in the "neutral site" game. The Gamecocks had just come off a 12-inning win against the Oklahoma Sooners less than 24 hours before, while the Tigers had two days of rest. However, fatigue was not a factor as the Gamecocks won the first game, 5–1, on a dominating complete game pitching performance by reliever Michael Roth, who had not started a game in more than a year. Carolina won the second game the following day, 4–3, to advance to the championship series against UCLA, who they defeated, 7–1 (Game 1) and 2–1 (Game 2) to win the NCAA Division I Baseball Championship. South Carolina went on to win the National Championship again against Florida in 2011 and lost to Arizona in the finals in 2012. Clemson has yet to pass the regionals since the loss.

Other varsity sports

Men's teams

| Sport | Last Matchup | All-Time Series | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Location | Winner | Score | Attendance | Leader | Record | |

| Basketball | December 6, 2023 | Littlejohn Coliseum Clemson, South Carolina |

Clemson | 72–67 | 9,000 | South Carolina | 92–81 |

| Soccer | September 1, 2023 | Riggs Field Clemson, South Carolina |

Clemson | 2–0 | Clemson | 34–17–1 | |

| Tennis | February 3, 2023 | Duckworth Family Facility Clemson, South Carolina |

South Carolina | 7–0 | South Carolina | 70–40–2 | |

Women's teams

| Sport | Last Matchup / Series | All-Time Series | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Location | Winner | Score | Attendance | Leader | Record | |

| Basketball | November 16, 2023 | Colonial Life Arena Columbia, South Carolina |

South Carolina | 109–40 | 16,820 | South Carolina | 35–33 |

| Soccer | August 17, 2023 | Riggs Field Clemson, South Carolina |

Tie | 0–0 | 3,917 | Clemson | 16–11–3 |

| Softball | March 28, 2023 | McWhorter Stadium Clemson, South Carolina |

Clemson | 10–0 (5) | 2,017 | Clemson | 5–0 |

| April 11, 2023 | Beckham Field Columbia, South Carolina |

Clemson | 4–3 | 2,165 | |||

| Tennis | February 14, 2023 | Duckworth Family Facility Clemson, South Carolina |

Clemson | 4–2 | South Carolina | 31–28 | |

| Volleyball | August 30, 2023 | Carolina Volleyball Center Columbia, South Carolina |

South Carolina | 3–1 | South Carolina | 43–23 | |

Discontinued sports

| Sport | Final Matchup | All-Time Series | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Location | Winner | Score | Leader | Record | ||

| Men's Swimming & Diving | October 29, 2011 | Westside Aquatic Center Greenville, South Carolina |

South Carolina | 162–137 | South Carolina | 35–13 | |

| Women's Swimming & Diving | October 29, 2011 | South Carolina | 191–108 | South Carolina | 22–14 | ||

| Women's Diving | November 9, 2016 | McHugh Natatorium Clemson, South Carolina |

South Carolina | 28–10 | South Carolina | 4–1 | |

- Clemson discontinued men's swimming & diving and women's swimming after the 2011–2012 season.

- Clemson sponsored women's diving as a standalone sport from the 2012–2013 season until the 2016–2017 season, when it was discontinued.

Blood drive

| Series Originated | 1985 |

| Overall Record | Clemson; 20-18 |

| Carolina (18) 1987 1993 1998 1999 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2017 |

Clemson (20) 1985 1986 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1994 1995 1996 1997 2000 2006 2007 2016 2018 2019 2021 2022 2023 |

The rivalry extends beyond sports to the annual blood drive between the two schools, also known as the "Blood Bowl".[112][113][114] Students, faculty and fans from the schools band together in an effort to collect blood before the holiday season when many are too busy to give blood. The drive is held from Monday through Friday the week before the football matchup. The University of South Carolina and Clemson University wrapped up their 38th annual blood drive in 2023, resulting in a fifth consecutive win for Clemson. Currently, Clemson holds a 20–18 advantage in the yearly competition.

The blood drive is sponsored by The Blood Connection and American Red Cross at the University of South Carolina with the help of the University of South Carolina's Carolina Clemson Blood Drive Committee[115] in addition to the Men's Rugby team and the Gamma Lambda chapter of the Alpha Phi Omega national service fraternity at Clemson, and the two schools have collected 153,320 pints of blood over the past thirty five years. Everyone who gives blood receives a free shirt, with the graphic on the back usually featuring a Tiger and Gamecock together and a statement explaining that even though the competition is part of the rivalry, both schools share the common ground of giving blood.

It is one of the largest collegiate blood drives in the country.[116][117] According to Clemson President James Clements, the Blood Bowl has impacted more than 500,000 lives since 1985.[118]

Palmetto Series

On August 4, 2015, leaders from the South Carolina Department of Agriculture, Clemson University, and the University of South Carolina gathered at the South Carolina State House to announce the launch of the Certified SC Grown Palmetto Series, in which the Tigers and Gamecocks would compete for the Palmetto Series trophy based primarily on head-to-head athletic competition.[119][120]

As of 2023–24, the following thirteen sports count toward the series: baseball, men's basketball, women's basetball, women's cross country, football, men's golf, women's golf, men's soccer, women's soccer, softball, men's tennis, women's tennis, and volleyball. These are all sports that either compete head-to-head or face each other in the same tournament or meet. The winning team in each sport earns one point. Additionally, one point is awarded to the school with the most LIFE scholarship recipients, Palmetto Fellows scholarship recipients and entries in the Rival Play Second-Chance Promotion, respectively.[121][122]

South Carolina won the inaugural Palmetto Series in 2016 with a score of 10–5.[123][124]

South Carolina won the Palmetto Series for the second consecutive year in 2017 with a score of 8–7.[125][126] This remains the closest Palmetto Series in point differential.

South Carolina won the Palmetto Series for the third consecutive year in 2018 with a score of 9–5.[127][128]

South Carolina won the Palmetto Series for the fourth consecutive year in 2019 with a score of 9.5–4.5.[129][130]

There was no Palmetto Series in 2020, 2021 or 2022 due to COVID-19 restrictions.[2] The "points chase" resumed in 2022–23 and soon had a new sponsor, the South Carolina Education Lottery.[131][132][133]

South Carolina won the Palmetto Series for the fifth consecutive year in 2023 with a score of 8–5. Additionally, it was the first Palmetto Series in which South Carolina swept Clemson in the four major sports (football, men's basketball, women's basketball, and baseball).[3][134] Clemson has yet to win a Palmetto Series trophy.

Clemson currently leads the 2024 Palmetto Series by a score of 4–3.[135][136]

See also

References

- ↑ "2022-23 Palmetto Series". University of South Carolina Athletics. September 21, 2022. Retrieved July 30, 2023.

- 1 2 "Gamecocks look to claim Palmetto Series for 5th time". Gamecocks look to claim Palmetto Series for 5th time - The Daily Gamecock at University of South Carolina. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- 1 2 "Gamecocks Take Fifth-Straight Palmetto Series Title over Tigers". WSPA 7NEWS. April 21, 2023. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ↑ "Certified SC Grown Palmetto Series Announced - Clemson Tigers Official Athletics Site". September 23, 2015. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ↑ "Ranking the top 25 rivalries in college sports". Saturday Down South. February 4, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ↑ "What are the best rivalries in college athletics? It starts in North Carolina". College Sports Wire. February 8, 2023. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ↑ Sports, Athlon (November 21, 2022). "Ranking the Top 25 Rivalries in College Football History". AthlonSports.com | Expert Predictions, Picks, and Previews. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ↑ Humphrey, Chris. "College Football: The 50 Best Rivalries in College Football". Bleacher Report. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ↑ "The 25 best rivalries in college football". Yardbarker. May 16, 2022. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ↑ "Atlantic Coast Conference – Official Athletics Site". www.theacc.com.

- ↑ "Southeastern Conference". Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ↑ "Clemson, South Carolina enter Palmetto State's biggest rivalry on three-game win streaks". Yahoo News. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ↑ "History of the Game: South Carolina vs. Clemson". Columbia Metropolitan Magazine. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ↑ Elsey, Jacob (July 31, 2020). "South Carolina football: The most iconic moments in the Palmetto State rivalry". Garnet and Cocky. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ↑ Inabinett, Mark (August 3, 2011). "Countdown to Football: 31 Days -- College football gets new oldest rivalry". al. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ↑ "Clemson-Carolina: The end of Big Thursday". The Clemson Insider. November 21, 2019. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ↑ "Clemson-South Carolina officially dubbed 'The Palmetto Bowl'". November 26, 2014.

- 1 2 Ablon, Matthew. "Clemson-South Carolina rivalry game cancelled after SEC moves to conference-only games". FOX Carolina.

- ↑ "Winsipedia - Clemson Tigers vs. South Carolina Gamecocks football series history". Winsipedia. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ↑ Gemei, Carmine; Staff, FOX Carolina News (November 25, 2023). "Clemson def. South Carolina 16-7 to win 120th Palmetto Bowl". https://www.foxcarolina.com. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ↑ Hollis 1951, p. 18

- ↑ Hollis 1951, pp. 212–225

- ↑ Hollis 1956, p. 32

- ↑ Hollis 1956, p. 79

- ↑ Hollis 1956, p. 89

- ↑ Hollis 1956, p. 102

- ↑ "History of Clemson University". Clemson University. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ↑ Ball 1932, p. 210

- 1 2 3 4 Hollis 1956, p. 134

- ↑ Ball 1932, p. 212

- 1 2 3 Hollis 1956, p. 138

- 1 2 Hollis 1956, p. 152

- ↑ Hollis 1956, p. 135

- ↑ Hollis 1956, p. 139

- ↑ Hollis 1956, p. 140

- ↑ Hollis 1956, pp. 139–140

- ↑ Hollis 1956, p. 150

- ↑ Hollis 1956, p. 146

- ↑ Simkins, Francis Butler (2002). Pitchfork Ben Tillman. University of South Carolina Press. p. 122.

- ↑ Hollis 1956, p. 143

- ↑ Hollis 1956, p. 144

- ↑ Hollis 1956, p. 148

- ↑ Ball 1932, p. 215

- 1 2 Cooper 2005, p. 212

- ↑ Simkins, Francis Butler (1964). The Tillman movement in South Carolina. Duke University Press. p. 84.

- 1 2 3 Cooper 2005, p. 164

- ↑ Hollis 1956, p. 151

- ↑ Cooper 2005, p. 163

- ↑ Ball 1932, p. 209

- ↑ Cooper 2005, p. 167

- ↑ Edgar 1998, p. 437

- 1 2 Cooper 2005, p. 206

- ↑ Hollis 1956, p. 157

- ↑ Edgar 1998, pp. 437, 439

- ↑ Edgar 1998, p. 439

- ↑ Lesesne 2001, p. 3

- ↑ Lesesne 2001, p. 109

- ↑ "Greenville Tech – 50 Years". Archived from the original on April 17, 2016. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ↑ Lesesne 2001, p. 178

- ↑ "USC Sumter - USC Sumter | University of South Carolina".

- ↑ "Historical Enrollment 1893 to present". www.clemson.edu.

- ↑ "Enrollment Data – Office of Institutional Research, Assessment, and Analytics – University of South Carolina". ipr.sc.edu.

- ↑ "New Palmetto Bowl trophy unveiled". https://www.wistv.com/. November 27, 2015.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - 1 2 "Winsipedia - Clemson Tigers vs. South Carolina Gamecocks football series history". Winsipedia.

- ↑ College football gets new oldest rivalry, College Football gets new oldest rivalry.

- ↑ NCAA football records Archived December 22, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, p. 118.

- ↑ "Clemson-Carolina: The end of Big Thursday". The Clemson Insider. November 21, 2019. Retrieved September 7, 2023.

- ↑ "South Carolina Gamecocks football all-time record, wins, and statistics". winsipedia.com.

- ↑ "Clemson Tigers football all-time record, wins, and statistics". winsipedia.com.

- ↑ Davis, Jess (November 14, 2007). "Tiger Burn comes under fire". The Daily Gamecock. p. 1. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ↑ "Clemson students to hold pep rally, Cocky 'funeral'". February 8, 2012. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ↑ "Tiger Burn update". The Daily Gamecock. November 15, 2007. p. 1. Retrieved May 18, 2022.

- ↑ "Metrobeat.net". metrobeat.net. Archived from the original on July 22, 2003.

- ↑ Lesesne 2001, p. 27

- ↑ "Tigers-Gamecocks in annual classic". Miami Herald. October 23, 1957.

- ↑ T&D Staff (November 26, 2011). "No law needed to require rivals to play big game". The Times and Democrat. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ↑ Vint, Patrick (June 11, 2013). "A Brief History of Conference Realignment, Part 5: The Carolignians and the Carolinas". Black Heart Gold Pants. SB Nation. Retrieved August 12, 2016.

- ↑ Ellison, Virginia (November 23, 2021). "October, 1959: October Saw the Last "Big Thursday" Football Game in 1959". South Carolina Historical Society. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ "Tigers Beat USC, 12 To 2, Before Record Crowd". The Greenville News. November 13, 1960. p. 1. Retrieved September 8, 2023.

- ↑ "Football Game Program Feature: November 22, 1963". Clemson Tigers Official Athletics Site. November 22, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ "Clemson Athletics Black History: Marion Reeves". Clemson Tigers Official Athletics Site. February 13, 2021. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ↑ Khaalid, Dara (February 13, 2023). "Clemson University's first Black football player reflects on legacy, NFL career". ABC News 4. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ↑ "Football pioneer Carlton Haywood reflects on his place in Gamecock history". University of South Carolina Athletics. June 30, 2020. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ↑ "Carlton Haywood College Stats, School, Draft, Gamelog, Splits". College Football at Sports-Reference.com. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ↑ "Jackie Brown College Stats, School, Draft, Gamelog, Splits". College Football at Sports-Reference.com. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ↑ "Gamecocks Celebrate First African-American Student-Athletes". University of South Carolina Athletics. November 18, 2013. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ↑ "Clemson Defeats South Carolina, 17 to 7, Before Record Crowd of 57,242". The New York Times. November 28, 1971. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ↑ "Winsipedia - Clemson Tigers vs. South Carolina Gamecocks football series history". Winsipedia. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ Will Vandervort (November 26, 2008). ""The Catch" Lives On". Scout.com. Retrieved September 3, 2009.

- ↑ "The Catch, 1977 CU-USC Game". Clemson Tigers Official Athletics Site. November 26, 2016. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ "Remember When? 1981 Clemson-Carolina". 247Sports. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ "Gamecock '84 win made season even more special". Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ↑ "100 Years of Rivalry: Game Recaps - The Official Athletic Site of the Atlantic Coast Conference". Archived from the original on September 17, 2012. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- ↑ "Clemson 45, South Carolina 0 - UPI Archives". UPI. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ Asher, Mark (January 19, 1990). "CLEMSON COACH FORD RESIGNS". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ "Where are they now: Steve Taneyhill". ESPN.com. September 18, 2009. Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ↑ "A Step Ahead". Retrieved October 5, 2014.

- ↑ Raynor, Josh Kendall and Grace. "Once and for all, was it the Push-Off Game or The Catch II?". The Athletic. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ "South Carolina 20, Clemson 15 - UPI Archives". UPI. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ "Clemson vs. Duke Moved To December 1". Clemson Tigers Official Athletics Site. September 17, 2001. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ Bouchard, Kiley. "A look back at the infamous 2004 Clemson vs. South Carolina game". The Tiger. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ↑ "Connor Shaw". University of South Carolina Athletics. June 22, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ "Winsipedia - Clemson Tigers vs. South Carolina Gamecocks football series history". Winsipedia. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ Knibbe, Ben (November 30, 2013). "South Carolina topples Clemson 31-17". SBNation.com. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ↑ Keepfer, Scott. "COVID-19, SEC decision will derail Clemson vs. South Carolina game in 2020". The Greenville News.

- ↑ "Clemson, South Carolina enter Palmetto State's biggest rivalry on three-game win streaks". Yahoo News. November 22, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ↑ Walsh, Kelsey; Ross, Kendall; Roman, Carly. "Trump attends football game on Haley's home turf and other trail takeaways". ABC News.

- ↑ "Clemson-South Carolina rivalry game cancelled after SEC moves to conference-only games".

- ↑ Etheridge, Mark (May 28, 2012). "Nine Innings: Finishing Second or Next to Last". SEBaseball.com. Archived from the original on October 9, 2014. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ↑ Fitt, Aaron (March 1, 2012). "Weekend Preview: South Carolina, Clemson Get Together Again". BaseballAmerica.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ↑ South Carolina Baseball Media Guide 2007, p. 111.

- ↑ Dyke, Allie Van (December 2, 2019). "Clemson University Wins Week-long Blood Donation Competition". Donate Blood - The Blood Connection. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ Sikes, Philip (November 27, 2023). "Clemson uses record 4,671 donations to claim Blood Bowl win over University of South Carolina". Clemson News. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ Mauro, Blake. "Clemson wins Blood Bowl for 5th straight year". The Tiger. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ "Carolina Clemson Blood Battle - Russell House | University of South Carolina".

- ↑ Dyke, Allie Van (December 2, 2019). "Clemson University Wins Week-long Blood Donation Competition". Donate Blood - The Blood Connection. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ "Carolina Clemson Blood Battle - Russell House | University of South Carolina". sc.edu. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ Mauro, Blake. "Clemson wins Blood Bowl for 5th straight year". The Tiger. Retrieved January 13, 2024.

- ↑ "Certified SC Grown Palmetto Series Announced". Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved August 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Certified SC Grown Palmetto Series Announced". University of South Carolina Athletics. August 4, 2015. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- ↑ "2023-24 Palmetto Series Presented by the SC Education Lottery". Clemson Tigers Official Athletics Site. July 1, 2023. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- ↑ "2023-24 Palmetto Series". University of South Carolina Athletics. August 28, 2023. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- ↑ "Palmetto Series". Palmetto Series. July 7, 2016.

- ↑ Glover, Emery (August 19, 2016). "Gamecocks celebrate inaugural Palmetto Series win with cookout". www.wistv.com. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- ↑ "Certified SC Grown – Palmetto Series". palmettoseries.com.

- ↑ "Gamecock Success Week: South Carolina Wins Palmetto Series". University of South Carolina Athletics. July 6, 2017. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- ↑ "Gamecocks Win Certified SC Grown Palmetto Series Third Year in a Row". University of South Carolina Athletics. June 29, 2018. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- ↑ "Clemson topped in 'Palmetto Series' for third-straight year". TigerNet.com. June 30, 2018. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- ↑ "South Carolina Wins 4th-Straight Palmetto Series Crown". ABC Columbia. June 25, 2019. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- ↑ "SC Again Takes Palmetto Series". WSPA 7NEWS. June 24, 2019. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- ↑ "Palmetto series gets new sponsor, SC Education Lottery". ABC Columbia. November 22, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ↑ "2022 Palmetto Series Presented by the SC Education Lottery". Clemson Tigers Official Athletics Site. September 14, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ↑ "2023-24 Palmetto Series Presented by the SC Education Lottery". Clemson Tigers Official Athletics Site. July 1, 2023. Retrieved September 10, 2023.

- ↑ "Gamecocks Take Fifth-Straight Palmetto Series Title over Tigers". University of South Carolina Athletics. April 20, 2023. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- ↑ "2023-24 Palmetto Series". University of South Carolina Athletics. August 28, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

- ↑ "2023-24 Palmetto Series Presented by the SC Education Lottery". Clemson Tigers Official Athletics Site. July 1, 2023. Retrieved January 11, 2024.

Sources

- Ball, William Watts (1932). The State That Forgot; South Carolina's Surrender to Democracy. The Bobbs-Merrill Company.

- Cooper, William (2005). The Conservative Regime: South Carolina, 1877–1890. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 1-57003-597-0.

- Edgar, Walter B. (1998). South Carolina: A History. University of South Carolina Press.

- Hollis, Daniel Walker (1951), University of South Carolina, vol. I, University of South Carolina Press

- Hollis, Daniel Walker (1956), University of South Carolina, vol. II, University of South Carolina Press

- Lesesne, Henry H. (2001). A History of the University of South Carolina, 1940–2000. University of South Carolina Press.