Cilicia

قيليقية Կիլիկիա Κιλικία Kilikya | |

|---|---|

Geographical region | |

.svg.png.webp) Cilicia in the Roman Empire | |

| Coordinates: 36°59′06″N 35°07′12″E / 36.985°N 35.120°E | |

| Country | Turkey |

| Largest city | Adana |

| Provinces | Mersin, Adana, Osmaniye, Hatay |

| Area | |

| • Total | 38,585.16 km2 (14,897.81 sq mi) |

| Population (2022)[1] | |

| • Total | 6,435,986 |

| • Density | 170/km2 (430/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Cilician(s) (English) Kilikyalı (Turkish) Կիլիկյան (Armenian) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (TRT) |

| Postal code prefixes | 33xxx, 01xxx, 80xxx, 31xxx |

| Area code(s) | 324, 322, 328, 326 |

| GRP (nominal) | $43.14 billion (2018)[2] |

| GRP per capita | $6,982 (2018)[2] |

| Languages | Turkish, Arabic, Kurmanji, Armenian |

Cilicia (/sɪˈlɪʃə/)[3][note 1] is a geographical region in southern Anatolia, extending inland from the northeastern coasts of the Mediterranean Sea. Cilicia has a population ranging over six million, concentrated mostly at the Cilicia plain. The region includes the provinces of Mersin, Adana, Osmaniye and Hatay.

Geography

Cilicia extends along the Mediterranean coast east from Pamphylia to the Nur Mountains, which separate it from Syria. North and east of Cilicia stand the rugged Taurus Mountains, which separate it from the high central plateau of Anatolia, and which are pierced by a narrow gorge called in antiquity the Cilician Gates.[4][5] Ancient Cilicia was naturally divided into Cilicia Trachea (Latin: Cilicia Aspera, west of the Limonlu River) and Cilicia Pedias (Latin: Cilicia Campestris,[6] east of the Limonlu).[7] Salamis, the city on the east coast of Cyprus, was included in the Roman province of Cilicia from 58 BCE until 27 BCE.

The Greeks invented for Cilicia an eponymous Hellene founder in the purely mythical Cilix, but the historic[8] founder of the dynasty that ruled Cilicia Pedias was Mopsus,[8][9] identifiable in Phoenician sources as Mpš,[10][11] the founder of Mopsuestia[11][12] who gave his name to an oracle nearby.[11] Homer mentions the people of Mopsus, identified as Cilices (Κίλικες), as from the Troad in the northwestern-most part of Anatolia.[13]

The English spelling Cilicia is the same as the Latin, as it was transliterated directly from the Greek form Κιλικία. The palatalization of c occurring in Western Europe in later Vulgar Latin (c. 500–700) accounts for its modern pronunciation in English.

Cilicia Trachea ("rugged Cilicia"—Greek: Κιλικία Τραχεῖα; the Assyrian Hilakku, classical "Cilicia")[14][15][16] is a rugged mountain district[17] formed by the spurs of Taurus, which often terminate in rocky headlands with small sheltered harbours,[18] features which, in classical times, made the coast a string of havens for pirates[18][19] and, in the Middle Ages, outposts for Genoese and Venetian traders. The district is watered by the Calycadnus[20] and was covered in ancient times by forests that supplied timber to Phoenicia and Egypt. Cilicia lacked large cities.[7]

Cilicia Pedias ("flat Cilicia"—Ancient Greek: Κιλικία Πεδιάς; Assyrian Kue), to the east, included the rugged spurs of Taurus and a large coastal plain, with rich loamy soil,[7] known to Greeks such as Xenophon (who passed through with his mercenary group of the Ten Thousand,[21]) for its abundance (euthemia),[22] filled with sesame and millet and olives[23] and pasturage for the horses imported into ancient Israel by King Solomon.[24] Many of its high places were fortified. The plain is watered by the three great rivers, the Cydnus (Tarsus Çay Berdan River), the Sarus (Seyhan), and the Pyramus (Ceyhan River), each of which brings down much silt from the deforested interior and which fed extensive wetlands. The Sarus now enters the sea almost due south of Tarsus, but there are clear indications that at one period it joined the Pyramus, and that the united rivers ran to the sea west of Kara-tash. Through the rich plain of Issus ran the great highway that linked east and west, on which stood the cities of Tarsus (Tarsa) on the Cydnus, Adana (Adanija) on the Sarus, and Mopsuestia (Missis) on the Pyramus.[7]

Climate

The climate of Cilicia shows significant differences between the mountains and the lower plains. At the lower plains, the climate reflects a typical Mediterranean style; summers are hot[25] while winters are mild, making the land, particularly, the eastern plains, fertile.[26] In the coldest month (January), the average temperature is 9 °C, and in the warmest month (August), the average temperature is 28 °C. The mountains of Cilicia have an inland climate with snowy winters. The average annual precipitation in the region is 647mm and the average number of rainy days in a year is 76. Mersin and surrounding areas have the highest average temperature in Cilicia. Mersin also has high annual precipitation (1096mm) and 85 rainy days in a year.

Geology

The mountains of Cilicia are formed from ancient limestones, conglomerate, marlstone, and similar materials. The Taurus Mountains are composed of karstic limestone, while its soil is also limestone-derived, with pockets of volcanic soil.[27] The lower plain is the largest alluvial plain in Turkey. Expansion of limestone formations and fourth-era alluvials brought by the rivers Seyhan and Ceyhan formed the plains of the region over the course of time.

Akyatan, Akyayan, Salt Lake, Seven lakes at Aladağ, and Karstik Dipsiz lake near Karaisalı are the lakes of the region. The reservoirs in the region are Seyhan, Çatalan, Yedigöze, Kozan and Mehmetli.

The major rivers in Cilicia are Seyhan, C eyhan, Berdan (Tarsus), Asi and Göksu.

- Seyhan River emerges from the confluence of Zamantı and Göksu rivers which originate from Kayseri Province and flows into the Gulf of Mersin. The river is 560 km long.

- Ceyhan River emerges from the confluence of the Aksu and Hurman rivers and flows towards Cape Hürmüz at the Gulf of İskenderun. It is 509 km long and it forms the Akyayan, Akyatan, and Kakarat lakes before flowing into the Mediterranean.

- Berdan River originates from the Taurus Mountains and flows into the Mediterranean south of Tarsus.

- Göksu river originates from the Taurus Mountains and flows into the Mediterranean 16 km southeast of Silifke. It forms the delta of Göksu, including Akgöl Lake and Paradeniz Lagoon.

History

Neolithic to Neo-Assyrian period

Cilicia was settled from the Neolithic period onwards.[28][29] Dating of the ancient settlements of the region from Neolithic to Bronze Age is as follows: Aceramic/Neolithic: 8th and 7th millennia BC; Early Chalcolithic: 5800 BC; Middle Chalcolithic (correlated with Halaf and Ubaid developments in the east): c. 5400–4500 BC; Late Chalcolithic: 4500 – c. 3400 BC; and Early Bronze Age IA: 3400–3000 BC; EBA IB: 3000–2700 BC; EBA II: 2700–2400 BC; EBA III A-B: 2400–2000 BC.[29]: 168–170

The area had been known as Kizzuwatna in the earlier Hittite era (2nd millennium BC).[31][32] The region was divided into two parts, Uru Adaniya (flat Cilicia), a well-watered plain, and "rough" Cilicia (Tarza), in the mountainous west.

The Cilicians appear as Hilikku in Assyrian inscriptions, and in the early part of the first millennium BC was one of the four chief powers of Western Asia.[7] Homer mentions the plain as the "Aleian plain" in which Bellerophon wandered,[33] but he transferred the Cilicians far to the west and north and made them allies of Troy. The Cilician cities unknown to Homer already bore their pre-Greek names: Tarzu (Tarsus), Ingira (Anchiale), Danuna-Adana, which retains its ancient name, Pahri (perhaps Mopsuestia), Kundu (Kyinda, then Anazarbus) and Azatiwataya (today's Karatepe).[34]

There exists evidence that circa 1650 BC both Hittite kings Hattusili I and Mursili I enjoyed the freedom of movement along the Pyramus River (now the Ceyhan River in southern Turkey), proving they exerted strong control over Cilicia in their battles with Syria. After the death of Murshili around 1595 BC, Hurrians wrested control from the Hitties, and Cilicia was free for two centuries. The first king of free Cilicia, Išputahšu, son of Pariyawatri, was recorded as a "great king" in both cuneiform and Hittite hieroglyphs. Another record of Hittite origins, a treaty between Išputahšu and Telipinu, king of the Hittites, is recorded in both Hittite and Akkadian.[35]

In the next century, the Cilician king Pilliya finalized treaties with both King Zidanta II of the Hittites and Idrimi of Alalakh, in which Idrimi mentions that he had assaulted several military targets throughout Eastern Cilicia. Niqmepa, who succeeded Idrimi as king of Alalakh, went so far as to ask for help from a Hurrian rival, Shaushtatar of Mitanni, to try and reduce Cilicia's power in the region. It was soon apparent, however, that increased Hittite power would soon prove Niqmepa's efforts to be futile, as the city of Kizzuwatna soon fell to the Hittites, threatening all of Cilicia. Soon after, King Sunassura II was forced to accept vassalization under the Hittites, becoming the last king of ancient Cilicia.[36] After the death of Mursili I, which led to a power struggle among rival claimants to the throne, eventually leading to the collapse of Hittite supremacy, Cilicia appeared to have regained its independence.[25]

In the 13th century BC a major population shift occurred as the Sea Peoples overran Cilicia. The Hurrians that resided there deserted the area and moved northeast towards the Taurus Mountains, where they settled in the area of Cappadocia.[37] In the 8th century BC, the region was unified under the rule of the dynasty of Mukšuš, whom the Greeks rendered Mopsos[9] and credited as the founder of Mopsuestia,[11] though the capital was Adana. Mopsuestia's multicultural character is reflected in the bilingual inscriptions of the ninth and eighth centuries, written both in Indo-European hieroglyphic Luwian and West Semitic Phoenician. In the ninth century BC, it became part of Assyria and remained so until the late seventh century BC.

Kingdom of Cilicia and Persian period

Before the early foundings of the kingdom, Cilicians had to protect themselves from Assyrian domination. After the dissolution of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in 612 BC, they established an independent kingdom from Syria. Given the fact that Cilicia was a strategically significant location, Cilicians were able to expand their kingdom as far north as the Halys River in a short period of time. With these expansions, the Cilician Kingdom became as strong as Babylonia, one of the contemporary powerhouses.

The Syennesis dynasty emerged in Cilicia and seemed to have been based in its western part during the reign of Appuašu.[38] The peaceful governance of the Syennesis dynasty sustained the kingdom and prevented the Achaemenid Empire from attacking Lydians after the Achaemenid invasions of Median lands. Appuašu, the son of Syennesis, defended the country against the Babylonian king Neriglissar, whose army reached Cilicia and crossed the Taurus mountain range.

The Achaemenids defeated the Lydians, and Appuašu had to recognize the authority of the Persians in 549 BC to keep the local administration with the Cilicians. Cilicia became an autonomous satrapy under the reign of Cyrus II.[39] Cilicians were independent in their internal affairs and kept this autonomy for almost 150 years. In 401, Syennesis III and his wife Epyaxa supported the revolt of Cyrus the Younger against his brother Artaxerxes II Mnemon. This was sound policy because otherwise, Cilicia would have been looted by the rebel army. However, after the defeat of Cyrus at Cunaxa, keeping Syennesis' position was difficult. Most scholars assume that this behavior marked the end of the independence of Cilicia. After 400, it became a normal satrapy.[40]

Under the Persian empire, Cilicia (in Old Persian: Karka)[41] was said to be governed by tributary native kings who bore a Hellenized name or the title of "Syennesis", and it was officially included in the fourth satrapy by Darius.[42] Xenophon found a queen in power, and no opposition was offered to the takeover of Cyrus the Younger.[7]

Roads

The great highway from the west existed before Cyrus conquered Cilicia. On its long rough descent from the Anatolian plateau to Tarsus, it ran through the narrow pass between walls of rock called the Cilician Gates. After crossing the low hills east of the Pyramus it passed through a masonry (Cilician) gate, Demir Kapu, and entered the plain of Issus. From that plain one road ran southward through another masonry (Syrian) gate to Alexandretta, and thence crossed Mt. Amanus by the Syrian Gate, Beilan Pass, eventually to Antioch and Syria. Another road ran northwards through a masonry (Armenian) gate, south of Toprak Kale, and crossed Mt. Amanus by the Armenian Gate, Baghche Pass, to northern Syria and the Euphrates. By the last pass, which was apparently unknown to Alexander, Darius crossed the mountains prior to the battle of Issus. Both passes are short and easy and connect Cilicia Pedias geographically and politically with Syria rather than with Anatolia.[7]

Hellenistic period

Alexander forded the Halys River in the summer of 333 BC, ending up on the border of southeastern Phrygia and Cilicia. He knew well the writings of Xenophon, and how the Cilician Gates had been "impassable if obstructed by the enemy". Alexander reasoned that by force alone he could frighten the defenders and break through, and he gathered his men to do so. In the cover of night, they attacked, startling the guards and sending them and their satrap into full flight, setting their crops aflame as they made for Tarsus. This good fortune allowed Alexander and his army to pass unharmed through the Gates and into Cilicia.[43] After Alexander's death it was long a battleground of the rival Hellenistic monarchs and kingdoms, and for a time fell under Ptolemaic dominion (i.e., Egypt), but finally came to the Seleucids, who, however, never held effectually more than the eastern half.[7] During the Hellenistic era, numerous cities were established in Cilicia, which minted coins showing the badges (gods, animals, and objects) associated with each polis.[44]

Roman and Byzantine periods

Cilicia Trachea became the haunt of pirates, who were subdued by Pompey in 67 BC following a Battle of Korakesion (modern Alanya), and Tarsus was made the capital of the Roman province of Cilicia. Cilicia Pedias became Roman territory in 103 BC first conquered by Marcus Antonius Orator in his campaign against pirates, with Sulla acting as its first governor, foiling an invasion of Mithridates, and the whole was organized by Pompey, 64 BC, into a province which, for a short time, extended to and included part of Phrygia.[7]

It was reorganized by Julius Caesar, 47 BC, and about 27 BC became part of the province Syria-Cilicia Phoenice. At first, the western district was left independent under native kings or priest-dynasts, and a small kingdom, under Tarcondimotus I, was left in the east;[45][7] but these were finally united to the province by Vespasian, AD 72.[46][7] Containing 47 known cities, it had been deemed important enough to be governed by a proconsul.[47]

Under Emperor Diocletian's Tetrarchy (c. 297), Cilicia was governed by a consularis; with Isauria and the Syrian, Mesopotamian, Egyptian and Libyan provinces, formed the Diocesis Orientis[7] (in the late 4th century the African component was split off as Diocese of Egypt), part of the pretorian prefecture also called Oriens ('the East', also including the dioceses of Asiana and Pontica, both in Anatolia, and Thraciae in the Balkans), the rich bulk of the eastern Roman Empire. After the division of the Roman Empire, Cilicia became part of the eastern Roman Empire, the Byzantine Empire. Cilicia was one of the most important regions of the classical world and can be considered as the birthplace of Christianity.[48][49]

Early Islamic period

In the 7th century Cilicia was invaded by the Muslim Arabs.[50] The area was for some time an embattled no-man's land. The Arabs succeeded in conquering the area in the early 8th century. Under the Abbasid Caliphate, Cilicia was resettled and transformed into a fortified frontier zone (thughur). Tarsus, re-built in 787/788, quickly became the largest settlement in the region and the Arabs' most important base in their raids across the Taurus Mountains into Byzantine-held Anatolia. The Muslims held the country until it was reoccupied by the Emperor Nicephorus II in 965.[7] From this period onward, the area increasingly came to be settled by Armenians, especially as Imperial rule pushed deeper into the Caucasus over the course of the 11th century.

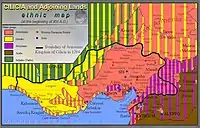

Armenian Cilicia and the Crusades

During the time of the First Crusade, the area was controlled by the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia. The Seljuk Turkish invasions of Armenia were followed by an exodus of Armenians migrating westward into the Byzantine Empire, and in 1080 Ruben, a relative of the last king of Ani, founded in the heart of the Cilician Taurus a small principality which gradually expanded into the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia. This Christian state, surrounded by Muslim states hostile to its existence, had a stormy history of about 300 years, giving valuable support to the Crusaders, and trading with the great commercial cities of Italy.[7]

It prospered for three centuries due to the vast network of fortifications which secured all the major roads as well as the three principal harbours at Ayas, Koŕikos, and Mopsuestia.[51] Through their complex alliances with the Crusader states, the Armenian barons and kings often invited Crusaders to maintain castles in and along the borders of the Kingdom, including Bagras, Trapessac, T‛il Hamtun, Harunia, Selefkia, Amouda, and Sarvandikar.

Gosdantin (r. 1095 – c. 1100) assisted the Crusaders on their march to Antioch, and was created knight and marquis. Thoros I (r. c. 1100 – 1129), in alliance with the Christian princes of Syria, waged successful wars against the Byzantines and Seljuk Turks. Levon II (Leo the Great (r. 1187–1219)), extended the kingdom beyond Mount Taurus and established the capital at Sis. He assisted the Crusaders, was crowned King by the Archbishop of Mainz, and married one of the Lusignans of the Crusader Kingdom of Cyprus.[7]

Mongols

Hetoum I (r. 1226–1270) made an alliance with the Mongols,[7] sending his brother Sempad to the Mongol court in person.[52][53] The Mongols then assisted with the defence of Cilicia from the Mamluks of Egypt, until the Mongols themselves converted to Islam.[7]

Turkmens

The Ilkhanate lost cohesion after the death of Abu Sa'id (r. 1316–1335), and thus could not support the Armenian Kingdom in guarding Cilicia. Internal conflicts within the Armenian Kingdom and the devastation caused by the Black Death that arrived in 1348, led nomadic Türkmens to turn their eyes towards unstable Cilicia. In 1352, Ramazan Beg led Turkmens settled south of Çaldağı and founded their first settlement, Camili. Later that year, Ramazan Beg visited Cairo and was licensed by the Sultan to establish the new frontier Turkmen Emirate in Cilicia.[54]

Collapse

When Levon V died (1342), John of Lusignan was crowned king as Gosdantin IV; but he and his successors alienated the native Armenians by attempting to make them conform to the Roman Church, and by giving all posts of honour to Latins, until at last the kingdom, falling prey to internal dissensions, ceded Cilicia Pedias to the Ramadanid-supported Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt in 1375.[7]

Mamluk and Turkmen rule

In 1359, Mamluk Sultanate Army marched into Cilicia and took over Adana and Tarsus, two major cities of the plain, leaving few castles to Armenians. In 1375, Mamluks gained the control of the remaining areas of Cilicia, thus ending the three centuries rule of Armenians. Cilicia Pedias became part of the Mamluk Sultanate in 1375.[7]

The Karamanid Principality, one of the Turkmen Anatolian beyliks emerged after the collapse of the Anatolian Seljuks, took over the rule of Cilicia Thracea.

Ottoman period

In 1516, Selim I incorporated the beylik into the Ottoman Empire after his conquest of the Mamluk state. The beys of Ramadanids held the administration of the Ottoman sanjak of Adana in a hereditary manner until 1608, with the last 92 years as a vassal of the Ottomans.

_2.017_Adana_Vilayet.jpg.webp)

Ottomans ended the Ramadanid administration of Adana sanjak in 1608, and ruled it directly from Constantinople then after. The autonomous sanjak was then split from the Aleppo Eyalet and established as a new province under the name of Adana Eyalet. A governor was appointed to administer the province. In late 1832, Eyalet of Egypt Vali Muhammad Ali Pasha invaded Syria, and reached Cilicia. The Convention of Kütahya that was signed on 14 May 1833, ceded Cilicia to the de facto independent Egypt. After the Oriental crisis, the Convention of Alexandria that was signed on 27 November 1840, required the return of Cilicia to Ottoman sovereignty. The American Civil War that broke out in 1861 disturbed the cotton flow to Europe and directed European cotton traders to fertile Cilicia. The region became the centre of cotton trade and one of the most economically strong regions of the Empire within decades. In 1869, Adana Eyalet was re-established as Adana Vilayet, after the re-structuring in the Ottoman Administration.

A thriving regional economy, the doubling of Cilician Armenian population due to flee from Hamidian massacres, and the end of autocratic Abdulhamid rule with the revolution of 1908, empowered the Armenian community and envisioned an autonomous Cilicia. Enraged supporters of Abdulhamid that organized under Cemiyet-i Muhammediye amidst the countercoup,[55] led to a series of anti-Armenian pogroms in 14–27 April 1909.[56] The Adana massacre resulted in the deaths of roughly 25,000 Armenians, orphaned 3500 children and caused heavy destruction of Christian neighbourhoods in the entire Vilayet.[57]

Cilicia section of the Berlin–Baghdad railway were opened in 1912, connecting the region to Middle East. Over the course of Armenian genocide, Ottoman telegraph was received by the Governor to deport the more than 70,000 Armenians of the Adana Vilayet to Syria.[58] Armenians of Zeitun had organized a successful resistance against the Ottoman onslaught. In order to finally subjugate Zeitun, the Ottomans had to resort to treachery by forcing an Armenian delegation from Marash to ask the Zeituntsis to put down their arms. Both the Armenian delegation, and later, the inhabitants of Zeitun, were left with no choice.[59]

Modern era

Armistice of Mudros that was signed on 30 October 1918 to end the World War I, ceded the control of Cilicia to France. French Government sent four battalions of the Armenian Legion in December to take over and oversee the repatriation of more than 170,000 Armenians to Cilicia.

On May 4, 1920, Armenian people declared the independence of Cilicia under the French mandate.

The French forces were spread too thinly in the region and, as they came under withering attacks by Muslim elements both opposed and loyal to Mustafa Kemal Pasha, eventually reversed their policies in the region. A truce arranged on May 28 between the French and the Kemalists, led to the retreat of the French forces south of the Mersin-Osmaniye railroad.

With the changing political environment and interests, the French further reversed their policy: The repatriation was halted, and the French ultimately abandoned all pretensions to Cilicia, which they had originally hoped to attach to their mandate over Syria.[60] Cilicia Peace Treaty was signed on 9 March 1921 between France and Turkish Grand National Assembly. The treaty did not achieve the intended goals and was replaced with the Treaty of Ankara that was signed on 20 October 1921. Based on the terms of the agreement, France recognized the end of the Cilicia War, and French troops together with the remaining Armenian volunteers withdrew from the region in early January 1922.[61]

Republic of Turkey

The region become part of the Republic of Turkey in 1921 with the signing of the Treaty of Ankara. On 15 April 1923, just before the signing of the Treaty of Lausanne, the Turkish government enacted the "Law of Abandoned Properties" which confiscated properties of Armenians and Greeks who were not present on their property. Cilicia were one of the regions with the most confiscated property, thus muhacirs (en: immigrants) from Balkans and Crete were relocated in the old Armenian and Greek neighbourhoods and villages of the region. All types of properties, lands, houses and workshops were distributed to them. Also during this period, there was a property rush of Muslims from Kayseri and Darende to Cilicia who were granted the ownership of large farms, factories, stores and mansions. Within a decade, Cilicia had a sharp change demographically, socially and economically and lost its diversity by turning into solely Muslim/Turkish.[62]

Administrative divisions

The modern Cilicia is split into four administrative provinces: Mersin, Adana, Osmaniye and Hatay. Each province is governed by the Central Government in Ankara through an appointed Provincial governor. Provinces are then divided into districts governed by the District Governors who are under the provincial governors.

| Province | Seat | Area (km2) | Districts (West to East) | Population | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mersin | Mersin | 15,853 | Anamur, Bozyazı, Aydıncık, Gülnar, Mut, Silifke, Erdemli, Mezitli, Yenişehir Toroslar, Akdeniz, Çamlıyayla, Tarsus | 1,891,145 |  |

| Adana | Adana | 14,030 | Seyhan, Çukurova, Yüreğir, Sarıçam, Pozantı, Karaisalı, Karataş, Yumurtalık (Ayas), Ceyhan, İmamoğlu, Aladağ (Karsantı), Kozan(Sis), Feke (Vahka), Saimbeyli (Hadjin), Tufanbeyli | 2,263,373 |  |

| Osmaniye | Osmaniye | 3,767 | Sumbas, Kadirli, Toprakkale (Tall Hamdūn), Düziçi, Osmaniye, Hasanbeyli, Bahçe | 553,012 |  |

| Hatay | Antakya | 5,524 | Erzin, Dörtyol (Chork Marzban), Hassa, İskenderun, Arsuz, Belen, Kırıkhan, Samandağ, Antakya, Defne, Reyhanlı, Kumlu, Yayladağı, Altınözü | 1,670,712 |  |

Demographics

Cilicia is heavily populated due to its abundant resources, climate and plain geography. The population of Cilicia as of December 31, 2022 is 6,435,986.[1]

Hatay is the most rural province of Cilicia and also Hatay is the only province that the rural population is rising and the urban population is declining. The major reason is the mountainous geography of Hatay.

Significant Christian communities (Antiochian Greek Christians and Armenians) found in Adana, İskenderun, and Mersin.[63]

Adana Province is the most urbanized province, with most of the population centred in the city of Adana. Mersin Province has a larger rural population than Adana Province, owing to its long and narrow stretch of flat land in between the Taurus Mountains and the Mediterranean.

| Rank | Province | Pop. | Rank | Province | Pop. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Adana  Mersin |

1 | Adana | Adana | 1,797,136 | 11 | Silifke | Mersin | 127,849 |  Antakya  Tarsus |

| 2 | Mersin | Mersin | 1,064,750 | 12 | Kadirli | Osmaniye | 126,941 | ||

| 3 | Antakya | Hatay | 555,833 | 13 | Samandağ | Hatay | 123,999 | ||

| 4 | Tarsus | Mersin | 347,314 | 14 | Kırıkhan | Hatay | 119,854 | ||

| 5 | Osmaniye | Osmaniye | 279,992 | 15 | Reyhanlı | Hatay | 105,309 | ||

| 6 | İskenderun | Hatay | 250,976 | 16 | Arsuz | Hatay | 99,480 | ||

| 7 | Ceyhan | Adana | 159,955 | 17 | Düziçi | Osmaniye | 85,118 | ||

| 8 | Erdemli | Mersin | 147,512 | 18 | Anamur | Mersin | 66,828 | ||

| 9 | Kozan | Adana | 132,320 | 19 | Mut | Mersin | 62,803 | ||

| 10 | Dörtyol | Hatay | 127,989 | 20 | Altınözü | Hatay | 60,861 | ||

Economy

Cilicia is well known for the vast fertile land and highly productive agriculture. The region is also industrialized; Tarsus, Adana and Ceyhan host numerous plants. Mersin and İskenderun seaports provide transportation of goods manufactured in Central, South and Southeast Anatolia. Ceyhan hosts oil, natural gas terminals as well as refineries and shipbuilders.

Natural resources

Agriculture

The Cilicia plain has some of the most fertile soil in the world in which 3 harvests can be taken each year. The region has the second richest flora in the world and it is the producer of all agricultural products of Turkey except hazelnut and tobacco. Cilicia leads Turkey in soy, peanuts and corn harvest and is a major producer of fruits and vegetables. Half of Turkey's citrus export is from Cilicia. Anamur is the only sub-tropical area of Turkey where bananas, mango, kiwi and other sub-tropical produce can be harvested.

Cilicia is the second largest honey producer in Turkey after the Muğla–Aydın region.[65] Samandağ, Yumurtalık, Karataş and Bozyazı are some of the towns in the region where fishing is the major source of income. Gray mullet, red mullet, sea bass, lagos, calamari and gilt-head bream are some of the most popular fish in the region. There are aquaculture farms in Akyatan, Akyağan, Yumurtalık lakes and at Seyhan Reservoir. While not as common as other forms of agriculture, dairy and livestock are also produced throughout the region.

Mining

- Zinc and lead: Kozan-Horzum seam is the major source.

- Chrome is found around Aladağlar.

- Baryte resources are around Mersin and Adana.

- Iron is found around Feke and Saimbeyli.

- Asbestos mines are mostly in Hatay Province.

- Limestone reserves are very rich in Cilicia. The region is home to four lime manufacturing plants.

- Pumice resources are the richest in Turkey. 14% of country's reserves are in Cilicia.

Manufacturing

Cilicia is one of the first industrialized regions of Turkey. With the improvements in agriculture and the spike of agricultural yield, agriculture-based industries are built in large numbers. Today, the manufacturing industry is mainly concentrated around Tarsus, Adana and Ceyhan. Textile, leather tanning and food processing plants are plentiful. İsdemir is a large steel plant located in İskenderun.

The petrochemical industry is rapidly developing in the region with the investments around the Ceyhan Oil Terminal. Petroleum refineries are being built in the area. Ceyhan is also expected to host the shipbuilding industry.

Commerce

Adana is the commercial centre of the region where many of the public and private institutions have their regional offices. Mersin and Antakya are also home to regional offices of public institutions. Many industry fairs and congresses are held in the region at venues such as the TÜYAP Congress and Exhibition Centre in Adana and the Mersin Congress Centre.

Mersin Seaport is the third largest seaport in Turkey, after Istanbul and İzmir. There are 45 piers in the port. The total area of the port is 785 square kilometres (194,000 acres), and the capacity is 6,000 ships per year.

İskenderun Seaport is used mostly for transfers to Middle East and Southeastern Turkey.[66]

Ceyhan Oil Terminal is a marine transport terminal for the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline (the "BTC"), the Kirkuk–Ceyhan Oil Pipeline, the planned Samsun-Ceyhan and the Ceyhan-Red Sea pipelines. Ceyhan will also be a natural gas terminal for a planned pipeline to be constructed parallel to the Kirkuk-Ceyhan oil pipeline, and for a planned extension of the Blue Stream Gas Pipeline from Samsun to Ceyhan.

Dörtyol Oil Terminal is a marine transport terminal for Batman-Dörtyol oil pipeline which started operating in 1967 to market Batman oil. The pipeline is 511 km long and has an annual capacity of 3.5 million tons.[67]

Tourism

While the region has a long coastline, international tourism is not at the level of the neighbouring Antalya Province. There are a small number of hotels between Erdemli and Anamur that attracts tourists. Cilicia tourism is mostly cottage tourism serving the Cilicia locals as well as residents of Kayseri, Gaziantep and surrounding areas. Between Silifke and Mersin, high-rise and low-rise cottages line the coast, leaving almost no vacant land. The coastline from Mersin to Karataş is mostly farmland. This area is zoned for resort tourism and is expected to have a rapid development within the next 20 years. Karataş and Yumurtalık coasts are home to cottages with a bird conservatory between the two areas. Arsuz is a seaside resort that is mostly frequented by Antakya and İskenderun residents.

Plateaus on the Taurus mountains are cooler escapes for the locals who wants to chill out from hot and humid summers of the lower plains. Gözne and Çamlıyayla (Namrun) in Mersin Province, Tekir, Bürücek and Kızıldağ in Adana Province, Zorkun in Osmaniye Province and Soğukoluk in Hatay Province are the popular high plain resorts of Cilicia which are often crowded in summer. There are a few hotels and camping sites in the Tekir plateau.

Balneary tourism

The region is a popular destination for thermal springs. Hamamat Thermal Spring, located on midway from Kırıkhan to Reyhanlı, has a very high sulphur ratio, making it the second in the world after a thermal spring in India.[68] It is the largest spa in the region and attracts many Syrians due to proximity. Haruniye Thermal Spring is located on the banks of the Ceyhan River near Düziçi town and has a serene environment. Thermal springs are a hot spot for people with rheumatism.[69] Kurttepe, Alihocalı and Ilıca mineral springs, all located in Adana Province, are popular for toxic cleansing. Ottoman Palace Thermal Resort & Spa in Antakya is one of Turkey's top resorts for revitalization.

Religious tourism

Lying at a crossroads of three major religions, namely Judaism, Christianity and Islam, the region is home to numerous landmarks that are important for people of faith. Tarsus is the birthplace of St. Paul, who returned to the city after his conversion. The city was a stronghold of Christians after his death. Ashab-ı Kehf cavern, one of the locations claimed to be the resting place of the legendary Seven Sleepers, holy to Christians and Muslims, is located north of Tarsus. Tarsus was the birthplace of Paul the Apostle.

Antakya is another destination for the spiritual world, where the followers of Jesus Christ were first called Christians. It is the home of Saint Peter, one of the 12 apostles of Jesus.[70] Antioch was called "the cradle of Christianity" as a result of its longevity and the pivotal role that it played in the emergence of both Hellenistic Judaism and early Christianity,[71] The Christian New Testament asserts that the name "Christian" first emerged in Antioch.[72] the Church of Saint Peter near Antakya (Antioch) is one of Christianity's oldest churches.[73]

Places of interest

Ancient sites

Kizkalesi (Maiden Castle), a fort on a small island across Kızkalesi township, was built during the early 12th century by Armenian kings of the Rubeniyan dynasty to defend the city of Korykos (present-day Kızkalesi).

Heaven & Hell, situated on a large hill north of Narlıkuyu, consists of the grabens resulting from assoil of furrings for thousands of years. The natural phenomenon of the grabens is named 'Hell & Heaven' because of the exotic effects on people. Visitors can access the cave of the mythological giant Typhon.[74]

The ancient Roman town of Soloi-Pompeiopolis, near the city of Mersin.

Yılanlı Kale (Castle of Serpents), an 11th-century Crusader castle built on a historical road connecting the Taurus mountains with the city of Antakya. The castle has 8 round towers, a military guardhouse and a church. It is located 5 km. west of Ceyhan.[75]

Anazarbus Castle, built in the 3rd century, served as the centre of the ancient metropolis of Anavarza. The city was built on a hill and had strategic importance, controlling the Cilician plain. The main castle and the city walls represent remains of the city. The city wall is 1500m. long and 8-10m. high, with 4 entrances to the city. The castle is located 80 km. northeast of Adana.

Şar (Comona), an ancient city located in northernmost Cilicia, some 200 km. north of Adana, near Tufanbeyli. It was an historical centre of the Hittites. Remaining structures today include the amphitheatre built during the Roman period, ruins of a church from the Byzantine era and Hittite rock-works.[76]

The Church of St. Peter in Antakya was a cave on the slopes of Habibi Neccar mountain converted into a church. The church is known as the first Christians' traditional meeting place. Pope Paul VI declared the church a "Place of Pilgrimage" for Christians in 1963, and since then a special ceremony takes place on 29 June each year.

St. Simeon Monastery, a 6th-century giant structure built on a desolate hill 18 km south of Antakya. The most striking features of this monastery are its cisterns, its storage compartment, and the walls. It is believed that St. Simeon resided here atop a 20-meter stone column for 45 years.

Parks and conservation areas

Akyatan Lagoon is a large wildlife refuge which acts as a stopover for migratory birds voyaging from Africa to Europe. The wildlife refuge has a 14,700 ha (36,000-acre) area made up of forests, lagoon, marsh, sandy and reedy lands. Akyatan lake is a natural wonder with endemic plants and endangered bird species living in it together with other species of plants and animals. 250 species of birds are observed during a study in 1990. The conservation area is located 30 km south of Adana, near Tuzla.[77]

Yumurtalık Nature Reserve covers an area of 16,430 hectares within the Seyhan-Ceyhan delta, with its lakes, lagoons and wide collection of plant and animal species. The area is an important location for many species of migrating birds, the number gets higher during the winters when the lakes become a shelter when other lakes further north freeze.[78]

Aladağlar National Park, located north of Adana, is a huge park of around 55,000 hectares, the summit of Demirkazik at 3756 m is the highest point in the middle Taurus mountain range. There is a huge range of flora and fauna, and visitors may fish in the streams full of trout. Wildlife includes wild goats, bears, lynx and sable. The most common species of plant life is black pine and cluster pine trees, with some cedar dotted between, and fir trees in the northern areas with higher humidity. The Alpine region, from the upper borders of the forest, has pastures with rocky areas and little variety of plant life because of the high altitude and slope.[79]

Karatepe-Aslantaş National Park located on the west bank of Ceyhan River in Osmaniye Province. The park includes the Karatepe Hittite fortress and an open-air museum.

Tekköz-Kengerlidüz Nature Reserve, located 30 km north of Dörtyol, is known for having an ecosystem different from the Mediterranean. The main species of trees around Kengerliduz are beech, oak and fir, and around Tekkoz are hornbeam, ash, beach, black pine and silver birch. The main animal species in the area are wild goat, roe deer, bear, hyena, wild cat, wagtail, wolf, jackal and fox.[80]

Habibi Neccar Dağı Nature Reserve is famous for its cultural as well as natural value, especially for St Pierre Church, which was carved into the rocks. The Charon monument, 200 m north of the church, is huge sculpture of Haron, known as Boatman of Hell in mythology, carved into the rocks. The main species of tree are cluster pine, oaks and sandalwood. The mountain is also home to foxes, rabbits, partridges and stock doves. Nature reserve is 10 km east of Antakya and can be accessible by public transport.[81]

Education

There are numerous private primary and high schools besides the state schools in the region. Most popular high school in the region is Tarsus American College, founded as a missionary school in 1888 to serve Armenian community and then became a secular school in 1923. Adana Anatolian High School and Adana Science High School most important high schools in the Cilicia. In other cities, Anatolian High School and School for Science are the most popular high schools of the city.

The region is home to five state and two foundation universities.

Çukurova University is a state university founded in 1973 with the union of the faculties of Agriculture and Medicine.. Main campus is in the city of Adana, and the College of Tourism Administration is in Karataş. There is an engineering faculty in Ceyhan, and vocational schools in Kozan, Karaisalı, Pozantı and Yumurtalık. The university is one of the well-developed universities of Turkey with many cultural, social and athletic facilities, currently enrolls 40,000 students.[82]

Mersin University is a state university founded in 1992, and currently serving with 11 faculties, 6 colleges and 9 vocational schools. The university employs more than 2100 academicians and enrolls 26,980 students.[83] Main campus is in the city of Mersin. In Tarsus, there is Faculty of Technical Education and Applied Technology and Management College. In Silifke and Erdemli, university has colleges and vocational schools. There are also vocational schools in Anamur, Aydıncık, Gülnar, and Mut.

Mustafa Kemal University is a state university located in Hatay Province. University was founded in 1992, currently has 9 faculties, 4 colleges and 7 vocational schools. Main campus is in Antakya and Faculty of Engineering is in İskenderun. The university employs 708 academicians and 14,439 students as of 2007.[84]

Korkut Ata University was founded in 2007 as a state university with the union of colleges and vocational schools in Osmaniye Province and began enrollment in 2009. The university has 3 faculties and a vocational school at the main campus in the city of Osmaniye and vocational schools in Kadirli, Bahçe, Düziçi and Erzin. University employs 107 academicians and enrolled 4000 students in 2009.[85]

Adana Science and Technology University is a recently founded state university that is planned to have ten faculties, two institutions and a college. It will accommodate 1,700 academic, 470 administrative staff, and it is expected to enroll students by 2012.[86]

Çağ University is a not-for-profit tuition based university founded in 1997. It is located on midway from Adana to Tarsus. University holds around 2500 students, most of them commuting from Adana, Tarsus and Mersin.[87]

Toros University is a not-for-profit tuition based university located in Mersin. The university started enrolling students in 2010.[88]

Sports

Football is the most popular sport in Cilicia, professionally represented at all levels of the Football in Turkey.[89]

| Club | Sport | League | Venue (capacity) | Founded |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adana Demirspor | Football (men) | Süper Lig | New Adana Stadium (33,543) | 1940 |

| Hatayspor | Football (men) | Süper Lig | New Hatay Stadium (25000) | 1967 |

| Adanaspor | Football (men) | TFF First League | New Adana Stadium (33,543) | 1954 |

| İskenderun FK | Football (men) | TFF Second League | 5 Temmuz (8217) | 1978 |

| Yeni Mersin İdman Yurdu | Football (men) | TFF Second League | Mersin Arena (25000) | 2019 |

| Tarsus İdman Yurdu | Football (men) | TFF Third League | Burhanettin Kocamaz (6000) | 1923 |

| Osmaniyespor | Football (men) | TFF Third League | 7 Ocak (6635) | 2011 |

| Adana 1954 FK | Football (men) | TFF Third League | Burhanettin Kocamaz (6000) | 2019 |

| Silifke Belediyespor | Football (men) | TFF Third League | Silifke Şehir (4000) | 1964 |

| Adana Demirspor | Football (women) | Women's Super League | Muharrem Gülergin | 1940 |

| Club | Sport | League | Venue (capacity) | Founded |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mersin BŞB | Basketball (women) | Women's Super League | Edip Buran Arena (1750) | 1993 |

| Hatay BŞB | Basketball (women) | Women's Super League | Antakya Sport Hall (2500) | 2009 |

| Adana Basketbol Kulubü | Basketball (women) | Women's Super League | Adana Atatürk Sports Hall (2000) | 2000 |

| Mersin Basketbol Kulübü | Basketball (women) | Women's Super League | Edip Buran Arena (1750) | |

| Tosyalı Toyo Osmaniye | Basketball (women) | Women's Super League | Tosyalı Sports Hall | 2000 |

Transportation

Cilicia has a well-developed transportation system with two airports, two major seaports, motorways and railway lines on the historical route connecting Europe to Middle East.

Air

Cilicia is served by two airports. Adana Şakirpaşa Airport is an international airport that have flights to European destinations. There are daily domestic flights to Istanbul, Ankara, İzmir, Antalya and Trabzon. Adana Şakirpaşa Airport serves the provinces of Mersin, Adana and Osmaniye.

Hatay Airport, opened in 2007, is a domestic airport, and currently has flights to Istanbul, Ankara and Nicosia, TRNC. Hatay Airport mostly serves Hatay Province.

Another under construction airport is Çukurova Regional Airport, According to the newspaper Hürriyet, the project's cost will be 357 million Euro. When finished, it will serve to 15 million people, and the capacity will be doubled in the future.

Sea

There are daily seabus and vehicle-passenger ferry services from Taşucu to Kyrenia, Northern Cyprus. From Mersin port, there are ferry services to Famagusta.

Road

The O50–O59 motorways crosses Cilicia. Motorways of Cilicia extends to Niğde on the north, Erdemli on the west and Şanlıurfa on the east, and İskenderun on the south. State road D-400 connects Cilicia to Antalya on the west. Adana–Kozan, Adana–Karataş, İskenderun–Antakya–Aleppo double roads are other regional roads.

Railway

Parallel to the highway network in Cilicia, there is an extensive railway network. Adana-Mersin train runs as a commuter train between Mersin, Tarsus and Adana. There are also regional trains from Adana to Ceyhan, Osmaniye and İskenderun.

Society

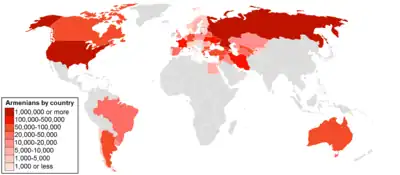

Cilicia was one of the most important regions for the Ottoman Armenians because it managed very well to preserve Armenian character throughout the years. In fact, the Cilician highlands were densely populated by Armenian peasants in small but prosperous towns and villages such as Hadjin and Zeitun, two mountainous areas where autonomy was maintained until the 19th century.[90][91] In ports and cities of the Adana plain, commerce and industry were almost entirely in the hands of the Armenians and they remained so thanks to a constant influx of Armenians from the highlands. Their population was continuously increasing in numbers in Cilicia in contrast to other parts of the Ottoman Empire, where it was, since 1878, decreasing due to repression.

Mythological namesake

Greek mythology mentions another Cilicia, as a small region situated immediately southeast of the Troad in northwestern Anatolia, facing the Gulf of Adramyttium. The connection (if any) between this Cilicia and the better-known and well-defined region mentioned above is unclear. This Trojan Cilicia is mentioned in Homer's Iliad and Strabo's Geography, and contained localities such as Thebe, Lyrnessus and Chryse (home to Chryses and Chryseis). These three cities were all attacked and sacked by Achilles during the Trojan War.

In Prometheus Bound (v 353), Aeschylus mentions the Cilician caves (probably Cennet and Cehennem), where the earth-born, hundred-headed monster Typhon dwelt before he withstood the gods and was stricken and charred by Zeus's thunderbolt.

Explanatory notes

References

- 1 2 "Address-based population registration system (ADNKS) results dated 31 December 2022, Favorite Reports" (XLS). TÜİK. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- 1 2 "81 ilin 2018 yılı GSYH ve büyüme karnesi". dunya.com. Dünya. 25 December 2019. Archived from the original on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ↑ "Cilicia". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary. Retrieved 6 April 2014.; "Cilicia". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 25 May 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- ↑ Ramsay, William Mitchell (1908) The Cities of St. Paul Their Influence on His Life and Thought: The cities of Eastern Asia Minor A.C. Armstrong, New York, page 112, OCLC 353134

- ↑ Baly, Denis and Tushingham, A. D. (1971) Atlas of the Biblical world World Publishing Company, New York, page 148, OCLC 189385

- ↑ Cilicia Campestris

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cilicia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 365–366.

- 1 2 Edwards, I. E. S. (editor) (2006) The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 2, Part 2, History of the Middle East and the Aegean Region c. 1380–1000 B.C. (3rd edition) Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, page 680 Archived 2022-10-30 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 0-521-08691-4

- 1 2 Fox, Robin Lane (2009) Travelling Heroes: In the Epic Age of Homer Alfred A. Knopf, New York, pages 211-224 Archived 2022-10-30 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0-679-44431-2

- ↑ Fox, Robin Lane (2009) Travelling Heroes: In the Epic Age of Homer Alfred A. Knopf, New York, page 216 Archived 2022-10-30 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 978-0-679-44431-2

- 1 2 3 4 Edwards, I. E. S. (editor) (2006) The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 2, Part 2, History of the Middle East and the Aegean Region c. 1380–1000 B.C. (3rd edition) Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, page 364 Archived 2022-10-30 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 0-521-08691-4

- ↑ Smith, William (1891) A Classical Dictionary of Biography, Mythology, and Geography based on the Larger Dictionaries (21st edition) J. Murry, London, page 456, OCLC 7105620

- ↑ Grant, Michael (1997). A Guide to the Ancient World. New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc. p. 168. ISBN 0-7607-4134-4.

- ↑ Sayce, A. H. (October 1922) "The Decipherment of the Hittite Hieroglyphic Texts" The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 4: pp. 537–572, page 554

- ↑ Edwards, I. E. S. (editor) (2006) The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 2, Part 2, History of the Middle East and the Aegean Region c. 1380–1000 B.C. (3rd edition) Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, page 422 Archived 2022-10-30 at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 0-521-08691-4

- ↑ Toynbee, Arnold Joseph and Myers, Edward DeLos (1961) A Study of History, Volume 7 Oxford University Press, Oxford, England, page 668, OCLC 6561573

- ↑ In general see: Bean, George Ewart and Mitford, Terence Bruce (1970) Journeys in Rough Cilicia, 1964–1968 (Volume 102 of Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Philosophisch-Historische Klasse.Denkschriften) Böhlau in Komm., Vienna, ISBN 3-205-04279-4

- 1 2 Rife, Joseph L. (2002) "Officials of the Roman Provinces in Xenophon's "Ephesiaca"" Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 138: pp. 93–108 , page 96

- ↑ See also the history of Side (Σίδη).

- ↑ Wainwright, G. A. (April 1956) "Caphtor - Cappadocia" Vetus Testamentum 6(2): pp. 199–210, pages 205–206

- ↑ Xenophon, Anabasis 1.2.22, noted the sesame and millet.

- ↑ Remarked by Robin Lane Fox, Travelling Heroes in the Epic Age of Homer, 2008:73 and following pages

- ↑ The modern plain has added cotton fields and orange groves.

- ↑ 1 Kings 10:28 - "Solomon’s horses were imported from Egypt and from Cilicia, where the king's merchants purchased them", noted by Fox 2008:75 note 15.

- 1 2 Vandekerckhove, Dweezil (2019). Medieval Fortifications in Cilicia: The Armenian Contribution to Military Architecture in the Middle Ages. Leiden: BRILL. p. 15. ISBN 978-90-04-41741-0.

- ↑ Mitchell, S. Augustus (1860). An Ancient Geography, Classical and Sacred. Philadelphia, PA: E.H. Butler & Co. p. 36.

- ↑ Vandekerckhove, Dweezil (2019). Medieval Fortifications in Cilicia: The Armenian Contribution to Military Architecture in the Middle Ages. Leiden: BRILL. p. 17. ISBN 978-90-04-41741-0.

- ↑ Akpinar, Ezgi (September 2004). "The Natural Landscape - Hydrology" (PDF). Hellenistic & Roman Settlement Patterns in the Plain of Issus & the Amanus Range (Master of Arts Thesis). Ankara: Bilkent University. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-09-26. Retrieved 2019-07-19.

- 1 2 Mellink, M.J. 1991. Anatolian Contacts with Chalcolithic Cyprus.

- ↑ McKeon, John F. X. (1970). "An Akkadian Victory Stele". Boston Museum Bulletin. 68 (354): 239. ISSN 0006-7997. JSTOR 4171539.

- ↑ Kapur, Selim; Eswaran, Hari; Blum, Winfried E. H. (2010-10-27). Sustainable Land Management: Learning from the Past for the Future. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-3-642-14782-1.

- ↑ Fox, Robin Lane (2008-09-04). Travelling Heroes: Greeks and their myths in the epic age of Homer. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-188986-3.

- ↑ Iliad 6.201.

- ↑ Fox 2008:75 notes these city names.

- ↑ Hallo, William W. (1971). The Ancient Near East: A History. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. pp. 111–112.

- ↑ Hallo, p. 112.

- ↑ Hallo, pp. 119–120.

- ↑ Bordman, John; Hammond, N.G.L.; Lewis, D.M.; Ostwald, M. (2002). The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume IV, Second Edition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 227. ISBN 0-521-22804-2.

- ↑ Kasım Ener. "Adana İl Yıllığı". Adana Valiliği. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ↑ Lendering, Jona. "Syennesis I". Livius. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

- ↑ "A2Pa - Livius".

- ↑ Grant, Michael (1997). A Guide to the Ancient World. New York: Barnes & Noble, Inc. p. 169. ISBN 0-7607-4134-4.

- ↑ Fox, Robin Lane (1974). Alexander the Great. The Dial Press. pp. 154–155. ISBN 9780803709454.

- ↑ For a full list of ancient cities and their coins see asiaminorcoins.com - ancient coins of Cilicia Archived 2013-10-31 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ WRIGHT, N.L. 2012: "The house of Tarkondimotos: a late Hellenistic dynasty between Rome and the East." Anatolian Studies 62: 69-88.

- ↑ A Dictionary of the Roman Empire. By Matthew Bunson. ISBN 0-19-510233-9. See page 90.

- ↑ Edwards, Robert W., "Isauria" (1999). Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World, eds., G.W. Bowersock, Peter Brown, & Oleg Grabar. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 377. ISBN 0-674-51173-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Mark, Joshua J. "Cilicia Campestris". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- ↑ "History of Cilicia". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ↑ Kaegi, Walter Emil (1969). "Initial Byzantine Reactions to the Arab Conquest". Church History. 38 (2): 139–149. doi:10.2307/3162702. ISSN 0009-6407. JSTOR 3162702. S2CID 162340890.

- ↑ Edwards, Robert W. (1987). The Fortifications of Armenian Cilicia: Dumbarton Oaks Studies XXIII. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University. pp. 3–288. ISBN 0-88402-163-7.

- ↑ Peter Jackson, Mongols and the West, p. 74. "King Het'um of Lesser Armenia, who had reflected profoundly upon the deliverance afforded by the Mongols from his neighbors and enemies in Rum, sent his brother, the Constable Smbat (Sempad) to Guyug's court to offer his submission."

- ↑ Angus Donal Stewart, "Logic of Conquest", p. 8. "The Armenian king saw an alliance with the Mongols – or, more accurately, swift and peaceful subjection to them – as the best course of action."

- ↑ Har-El, Shai (1995). Struggle for Domination in the Middle East: The Ottoman-Mamluk War, 1485-91. Leiden, New York, Köln: E.J. Brill. ISBN 978-9004101807.

- ↑ "106. yıldönümünde Adana Katliamı'nın ardındaki gerçekler". Agos Gazetesi. 4 October 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ↑ Yeghiayan, Puzant (1970), Ատանայի Հայոց Պատմութիւն [The History of the Armenians of Adana] (in Armenian), Beirut: Union of Armenian Compatriots of Adana, pp. 211–272

- ↑ See Raymond H. Kévorkian, "The Cilician Massacres, April 1909" in Armenian Cilicia, eds. Richard G. Hovannisian and Simon Payaslian. UCLA Armenian History and Culture Series: Historic Armenian Cities and Provinces, 7. Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers, 2008, pp. 351–353.

- ↑ "Adana araştırması ve saha çalışması". Hrant Dink Foundation. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ↑ Jernazian, Ephraim K. (1990). Judgment Unto Truth: Witnessing the Armenian Genocide. New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. pp. 53–55. ISBN 0-88738-823-X.

- ↑ Moumjian, Garabet K. "Cilicia Under French Administration: Armenian Aspirations, Turkish Resistance, and French Stratagems" in Armenian Cilicia, pp. 457–489.

- ↑ "Cilicia in the years 1918–1923". Zum.de. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ↑ "Ermeni Kültür Varlıklarıyla Adana" (PDF). HDV Yayınları. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ↑ Gorman, Anthony (2015). Diasporas of the Modern Middle East: Contextualising Community. Edinburgh University Press. p. 32. ISBN 9780748686131.

- ↑ "District Populations of Adana,Mersin,Hatay and Osmaniye". tuik.gov.tr. Retrieved 2022-05-05.

- ↑ "Türkiye'de Arıcılık". Assale. Archived from the original on April 8, 2022. Retrieved June 1, 2009.

- ↑ "İskenderun Port Authority". Republic of Turkey Privatization Administration. Archived from the original on 2016-12-27. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ↑ "Batman-Dörtyol Petrol Boru Hattı (Turkish)". BOTAŞ. Archived from the original on 2011-08-27. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ↑ "Hatay Hamamat Kaplıcası (Turkish)". Kaplıca ve Termal Turizm. Archived from the original on 2016-10-21. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ↑ "Haruniye Kaplıcaları (Turkish)". Kaplıca ve Termal Turizm. Archived from the original on 2016-08-06. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ↑ "Hatay". Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Archived from the original on 2014-10-23. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ↑ "The mixture of Roman, Greek, and Jewish elements admirably adapted Antioch for the great part it played in the early history of Christianity. The city was the cradle of the church." — "Antioch," Encyclopaedia Biblica, Vol. I, p. 186 (p. 125 of 612 in online .pdf file. Warning: Takes several minutes to download).

- ↑ "Acts of the Apostles 11:26".

- ↑ Clyde E. Fant, Mitchell Glenn Reddish, A guide to biblical sites in Greece and Turkey Archived 2022-10-30 at the Wayback Machine (Oxford University Press US, 2003), pg. 149

- ↑ "Heaven & Hell". ÇUKTOB. Archived from the original on 2012-02-27. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

Heaven & Hell consists of the grabens result from assoil of furrings in the thousands of years. Natural fenomen of this grabens is called as Heaven & Hell because of the exotic effects on people.You can go Heaven hole from an ancient path which has 452 steps and you can reach 260 meter long mythological giant Typhon cave.

- ↑ "Yılanlı Kale". ÇUKTOB. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ↑ "Adana Governorship (Turkish)".

- ↑ "Akyatan Bird Sanctuary". Çukurova Touristic Hoteliers Association. Archived from the original on 2011-10-09. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ↑ "Yumurtalık Nature Reserve". Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ↑ "Aladağlar National Park". Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ↑ "Tekkoz-Kengerlidüz Nature Reserve". Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ↑ "Habibi Neccar Dagi Nature Reserve". Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ↑ "ÇÜ'de Öğrenci Kayıtları (Turkish)". Haber FX. Archived from the original on 2012-08-02.

- ↑ "Student Statistics". Mersin University. Archived from the original on 2010-08-25. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ↑ "University History (Turkish)". Mustafa Kemal University. Archived from the original on 2018-10-28. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ↑ "Information about University". Korkut Ata University. Archived from the original on 2010-01-23. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ↑ "Adana'ya bilim üniversitesi(Turkish)". Radikal. Retrieved March 31, 2011.

- ↑ "Çağ University (Turkish)". Archived from the original on 2009-06-21.

- ↑ "Toros Üniversitesi'ne rektör atandı. (Turkish)". Mersin Ajans. Archived from the original on 2012-03-01. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ↑ "TFF Databank". Turkish Football Federation. Retrieved 2023-07-25.

- ↑ Bournoutian, Ani Atamian. "Cilician Armenia" in The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiquity to the Fourteenth Century. Ed. Richard G. Hovannisian. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997, pp. 283-290. ISBN 1-4039-6421-1.

- ↑ Bryce, James (2008). The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire. Frankfurt: Textor Verlag. pp. 465–467. ISBN 978-3-938402-15-3.

Further reading

- Rutishauser, Susanne. 2020. Siedlungskammer Kilikien. Studien zur Kultur- und Landschaftsgeschichte des Ebenen Kilikien. Schriften zur Vorderasiatischen Archäologie Bd. 16. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden. ISBN 978-3-447-11397-7.

- Pilhofer, Philipp. 2018. Das frühe Christentum im kilikisch-isaurischen Bergland. Die Christen der Kalykadnos-Region in den ersten fünf Jahrhunderten (PDF; 27,4 MB) (Texte und Untersuchungen zur Geschichte der altchristlichen Literatur, vol. 184). Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter (ISBN 978-3-11-057381-7).

- Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, No. 282/283, Symposium: Chalcolithic Cyprus. pp. 167–175.

- Engels, David. 2008. "Cicéron comme proconsul en Cilicie et la guerre contre les Parthes", Revue Belge de Philologie et d'Histoire 86, pp. 23–45.

- Pilhofer, Susanne. 2006. Romanisierung in Kilikien? Das Zeugnis der Inschriften (Quellen und Forschungen zur Antiken Welt 46). Munich: Herbert Utz Verlag (ISBN 3-8316-0538-6). And: 2., erweiterte Auflage, mit einem Nachwort von Philipp Pilhofer (Quellen und Forschungen zur Antiken Welt 60) Munich: Herbert Utz Verlag (ISBN 978-3-8316-7184-7)

External links

- Ancient Cilicia - texts, photographs, maps, inscriptions

- Jona Lendering, "Ancient Cilicia" Archived 2014-07-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Cilicia

- Photographs and Plans of the Churches and Fortifications in the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia

- Pilgrimages to Historic Armenia and Cilicia

- WorldStatesmen- Turkey

- Armenian Genocide Map's - Map of Kilikia (1909)