| Chiswick | |

|---|---|

| |

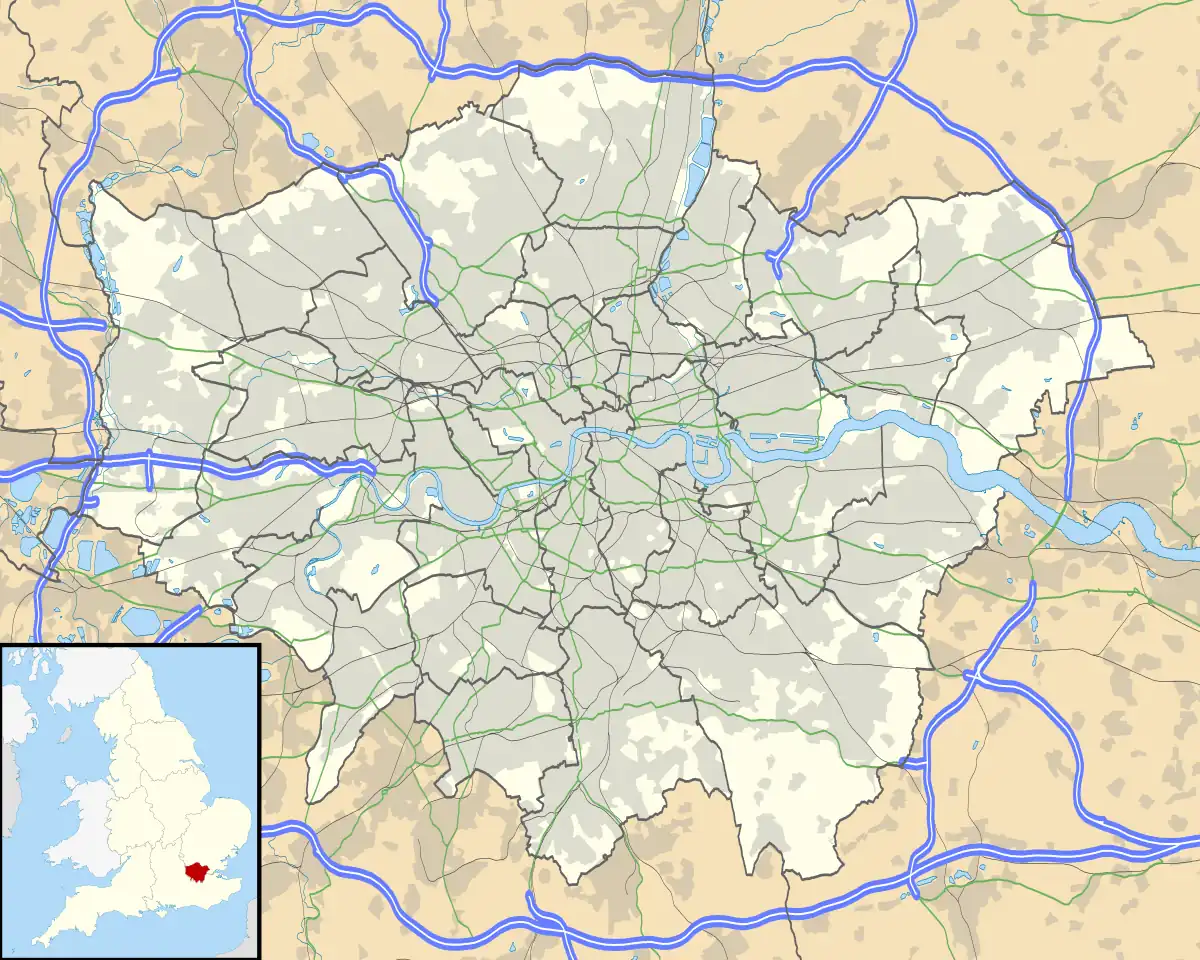

Chiswick Location within Greater London | |

| Area | 5.72 km2 (2.21 sq mi) |

| Population | 34,337 (Chiswick Homefields, Chiswick Riverside, Turnham Green wards 2011)[2] |

| • Density | 6,003/km2 (15,550/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | TQ205785 |

| • Charing Cross | 6 mi (9.7 km) E |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | W4 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

Chiswick (/ˈtʃɪzɪk/ ⓘ CHIZ-ik)[3] is a district in the London Borough of Hounslow, West London, England. It contains Hogarth's House, the former residence of the 18th-century English artist William Hogarth; Chiswick House, a neo-Palladian villa regarded as one of the finest in England; and Fuller's Brewery, London's largest and oldest brewery. In a meander of the River Thames used for competitive and recreational rowing, with several rowing clubs on the river bank, the finishing post for the Boat Race is just downstream of Chiswick Bridge.

Old Chiswick was an ancient parish in the county of Middlesex, with an agrarian and fishing economy beside the river; from the Early Modern period, the wealthy built imposing riverside houses on Chiswick Mall. Having good communications with London, Chiswick became a popular country retreat and part of the suburban growth of London in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was made the Municipal Borough of Brentford and Chiswick in 1932 and part of Greater London in 1965, when it merged into the London Borough of Hounslow. Modern Chiswick is an affluent area which includes the early garden suburb Bedford Park, Grove Park, the Glebe Estate, Strand-on-the-Green and tube stations Chiswick Park, and Turnham Green, as well as the Gunnersbury Triangle local nature reserve. Some parts of Bedford Park and Acton Green are in the Chiswick W4 postcode area but the London Borough of Ealing. The main shopping and dining centre is Chiswick High Road.

Chiswick Roundabout is the start of the North Circular Road (A406). At Hogarth Roundabout, the Great West Road from central London becomes the M4 motorway, while the Great Chertsey Road (A316) runs south-west, becoming the M3 motorway.

People who have lived in Chiswick include the poets Alexander Pope and W. B. Yeats, the Italian poet and revolutionary Ugo Foscolo, the painters Vincent van Gogh and Camille Pissarro, the novelist E. M. Forster, the rock musicians Pete Townshend, John Entwistle, and Phil Collins, the stage director Peter Brook, and the actress Imogen Poots.

History

Chiswick was first recorded c. 1000 as the Old English Ceswican meaning "Cheese Farm"; the riverside area of Duke's Meadows is thought to have supported an annual cheese fair up until the 18th century.[4][5] The area was settled in Roman times; an urn found at Turnham Green contained Roman coins, and Roman brickwork was found under the Sutton manor house.[6]

Old Chiswick grew up as a village around St Nicholas Church from c. 1181 on Church Street, its inhabitants practising farming, fishing and other riverside trades including a ferry, important as there were no bridges between London Bridge and Kingston throughout the Middle Ages.[7] The area included three other small settlements, the fishing village of Strand-on-the-Green, the hamlet of Little Sutton in the centre, and Turnham Green on the west road out of London.[7]

A decisive skirmish took place on Turnham Green early in the English Civil War. In November 1642, royalist forces under Prince Rupert, marching from Oxford to retake London, were halted by a larger parliamentarian force under the Earl of Essex. The royalists retreated and never again threatened the capital.[8]

From 1758 until 1929 the Dukes of Devonshire owned Chiswick House, and their legacy can be found in street names all over Chiswick.[lower-alpha 1][9]

In 1864, John Isaac Thornycroft, founder of the John I. Thornycroft & Company shipbuilding company, established a yard at Church Wharf at the west end of Chiswick Mall.[10][11] The shipyard built the first naval destroyer, HMS Daring of the Daring class, in 1893.[12] To cater for the increasing size of warships, Thornycroft moved its shipyard to Southampton in 1909.[13]

In 1822, the Royal Horticultural Society leased 33 acres (13.4 ha) of land in the area south of the High Road between what are now Sutton Court Road and Duke's Avenue.[14] This site was used for its fruit tree collection and its first school of horticulture, and housed its first flower shows. The area was reduced to 10 acres (4.0 ha) in the 1870s, and the lease was terminated when the Society's garden at Wisley, Surrey, was set up in 1904. Some of the original pear trees still grow in the gardens of houses built on the site.

The population of Chiswick grew almost tenfold during the 19th century, reaching 29,809 in 1901,[15] and the area is a mixture of Georgian, Victorian and Edwardian housing. Suburban building began in Gunnersbury in the 1860s and in Bedford Park, the first garden suburb, on the borders of Chiswick and Acton, in 1875.

During the Second World War, Chiswick was bombed repeatedly,[16] with both incendiary and high explosive bombs. Falling anti-aircraft shells and shrapnel also caused damage. The first V-2 rocket to hit London fell on Staveley Road, Chiswick, at 6.43pm on 8 September 1944, killing three people, injuring 22 others and causing extensive damage to surrounding trees and buildings. Six houses were demolished by the rocket and many more suffered damage.[17] There is a memorial where the rocket fell on Staveley Road, and a War Memorial at the east end of Turnham Green. By the start of the 21st century, Chiswick had become an affluent suburb.[18]

Governance

Chiswick St Nicholas was an ancient, and later civil, parish in the Ossulstone hundred of Middlesex.[20] Until 1834 its vestry governed most parish affairs. After the Poor Law Amendment Act (1834), local administration in Chiswick began to be devolved to authorities beyond the vestry. Then, Chiswick poor relief was administered by the Brentford Poor Law Union.[21] Briefly, from 1849 to 1855, responsibility for Chiswick drains and sewers passed to the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers under its 'Fulham and Hammersmith Sewer District.'[22] From 1858, under the Chiswick Improvement Act of that year,[22] responsibility for drains and sewers, paving and lighting was vested in an elected board of eighteen Improvement Commissioners.[22] This operated as Chiswick's secular local authority for a quarter of a century until its replacement with a Local Board in 1883.[22] In 1878 the parish gained a triangle of land in the east which had formed a detached part of Ealing.[23] From 1894 to 1927 the parish formed the Chiswick Urban District.[24][25] In 1927 it was abolished and its former area was merged with that of Brentford Urban District to form Brentford and Chiswick Urban District.[26] The amalgamated district became a municipal borough in 1932. The borough of Brentford and Chiswick was abolished in 1965, and its former area was transferred to Greater London to form part of the London Borough of Hounslow.[27] With these changes, Chiswick Town Hall is no longer the local government centre but remains an approved venue for marriage and civil partnership ceremonies.[28] Chiswick forms part of the Brentford and Isleworth Parliament constituency, having been part of the Brentford and Chiswick constituency between 1918 and 1974.[29] The Member of Parliament (MP) is Ruth Cadbury (Labour), elected at the May 2015 general election replacing Mary Macleod (Conservative). For elections to the London Assembly Chiswick is in the South West constituency, represented since 2000 by Tony Arbour, of the Conservative Party. For elections to Hounslow London Borough Council, Chiswick is represented by three electoral wards: Turnham Green, Chiswick Homefields and Chiswick Riverside. Each ward elects three councillors, who serve four-year terms. For 2010–14, all nine councillors were Conservatives.[30][31][32] It was one of 35 major centres identified in the statutory planning document of Greater London, the London Plan of 2008.[33]

Geography

Chiswick occupies a meander of the River Thames, 6 miles (9.7 km) west of Charing Cross. The district is built up towards the north with more open space in the south, including the grounds of Chiswick House and Duke's Meadows. Chiswick has one main shopping area, the Chiswick High Road, forming a long high street in the north, with additional shops on Turnham Green Terrace and Devonshire Road. The river forms the southern boundary with Kew, including North Sheen, Mortlake and Barnes in the London Borough of Richmond upon Thames. It includes the uninhabited island of Chiswick Eyot, joined to the mainland at low tide. In the east Goldhawk Road and British Grove border Hammersmith in the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham. In the north are Bedford Park (like Chiswick, within the London W4 postcode area) and South Acton in the London Borough of Ealing, with a boundary partially delineated by the District line. On the west, within Hounslow, are the districts of Gunnersbury, which is within the bounds of the early 19th century parish of Chiswick,[34] and Brentford.[35] A short distance south of the High Road in the centre of Chiswick is the Glebe Estate, consisting of small terraced houses built in the 1870s on glebe land once owned by the local church, and now a desirable place to live.[36] Chiswick is in the W4 postcode district of the London post town, which in a tribute to its ancient parish includes Bedford Park and Acton Green, mostly within the London Borough of Ealing.[37]

Some of the most beautiful period mansion blocks in Chiswick, such as Heathfield Court and Arlington Mansions, line the sides of Turnham Green – the site of the Battle of Turnham Green in 1642. Other suburbs of Chiswick include Grove Park (south of the A4, close to Chiswick railway station) and Strand on the Green, a fishing hamlet until the late 18th century.[38] As early as 1896, Bedford Park was advertised as being in Chiswick,[39] though at that time much of it was in Acton.[23]

Economy

Chiswick High Road contains a mix of retail shops, restaurants, food outlets and office and hotel space. The wide streets encourage cafes, pubs and restaurants to provide pavement seating. Lying between the offices at the Golden Mile Great West Road and Hammersmith, office developments and warehouse conversions to offices began from the 1960s. The first in 1961 was 414 Chiswick High Road on the site of the old Chiswick Empire. Between 1964 and 1966, the 18-storey IBM headquarters was built above Gunnersbury station, designed to accommodate 1500 people. It became the home of the British Standards Institution in 1994.[40] Chiswick has an annual book festival.[41]

Chiswick is home to the Griffin Brewery, where Fuller, Smith & Turner and its predecessor companies brewed their prize-winning ales on the same site for over 350 years. The original brewery was in the gardens of Bedford House in Chiswick Mall.[42]

A weekly farmers' market is held every Sunday by Grove Park Farm House, Duke's Meadows.[43] A monthly flower market is held on the first Sunday of each month on Chiswick High Road in the old market place, now mostly used as a car park, near the Hogarth statue.[44] An antiques market is to be held on the second Sunday of each month, and a "Cheese and Provisions" market with 23 stalls on the third and fourth Sundays of each month in the same area, so there will in effect be a weekly market event on the High Road once again.[45][46]

Points of interest

Chiswick House

Chiswick House was designed by the Third Earl of Burlington, and built for him, in 1726–29 as an extension to an earlier Jacobean house (subsequently demolished in 1788); it is considered to be among the finest surviving examples of Palladian architecture in Britain, with superb collections of paintings and furniture. Its surrounding grounds, laid out by William Kent, are among the most important historical gardens in England and Wales, forming one of the first English landscape gardens.[47] It was used as an asylum from 1892 to 1928; up to 40 private patients were housed in wings which were demolished in 1956 when the house was restored.[48]

Churches

St Nicholas Church, near the river Thames, has a 15th-century tower, although the remainder of the church was rebuilt by J.L. Pearson in 1882–84. Monuments in the churchyard mark the burial sites of the 18th-century English artist William Hogarth and William Kent, the architect and landscape designer; the churchyard also houses a mausoleum (for Philip James de Loutherbourg) designed by John Soane, and the tomb of Josiah Wedgwood's business partner, Thomas Bentley, designed by Thomas Scheemakers.[49] One of Oliver Cromwell's daughters, Mary Fauconberg, lived at Sutton Court and is buried in the churchyard.[50] Enduring legend has it that the body of Oliver Cromwell was also interred with her, though as the Fauconbergs did not move to Sutton Court until 15 years after his disinterment, it is more likely he was reburied at their home at Newburgh Priory.[50] Private Frederick Hitch VC, hero of Rorke's Drift, is also buried there.[51]

The church of St Michael, Sutton Court was designed by W. D. Caröe in 1908–1909. It is a red brick building on Elmwood road, in Tudor style.[52] St Paul's Church, Grove Park is a Gothic style stone building designed by H. Currey. It was built largely at the Duke of Devonshire's expense in 1872.[52]

St Michael and All Angels, Bedford Park was initially a temporary iron building from 1876 on Chiswick High Road facing Chiswick Lane. The current building's foundation stone was laid in 1879 and consecrated in 1880. It was designed, along with much of Bedford Park, by Norman Shaw, and was called "a very lovely church" by John Betjeman. It is an Anglo-Catholic church, and was attacked on the day it was consecrated for "Popish and Pagan mummeries" by the brewer Henry Smith, churchwarden of St Nicholas, Chiswick.[53]

Christ Church, Turnham Green is an early Victorian Gothic building of flint with stone dressings. The main part of the building, by George Gilbert Scott and W. B. Moffat, is from 1843; the chancel and northeast chapel were added in 1887 by J. Brooks.[52]

Chiswick's principal Roman Catholic church, Our Lady of Grace and St Edward (the Confessor) in the Diocese of Westminster, lies on the corner of Duke's Avenue and the High Road. It is a red brick building; the parish was founded in 1848, a school began c. 1855, and a church was opened by Cardinal Wiseman on the present site in 1864. It was replaced by the present building in 1886, opened by Cardinal Manning. The heavy debts incurred were paid off and the church consecrated in 1904. The square tower was added after the First World War by Canon Egan as a war memorial.[54]

The Cathedral of the Nativity of the Most Holy Mother of God and the Holy Royal Martyrs with its characteristic blue onion dome with gold stars is in Harvard Road. The Russian Orthodox church built it in 1998.[55]

Chiswick Mall

Chiswick Mall is a waterfront street on the north bank of the River Thames in the oldest part of Chiswick near St Nicholas Church. It consists mainly of some thirty "grand houses"[56] from the Georgian and Victorian eras, many of them now listed buildings, overlooking the street on the north side; their gardens are on the other side of the street beside the river.[57] The largest and finest[56] house on the street is Walpole House, a Grade I listed building; part of it is Tudor, but the building now visible is late 17th to early 18th century.[58]

Strand-on-the-Green

Strand-on-the-Green is the most westerly part of Chiswick, "particularly picturesque"[59] with a paved riverside path fronted by a row of "imposing"[59] 18th-century houses, interspersed with three riverside pubs. The low-lying path is flooded at high tides. It became fashionable in 1759 when Kew Bridge opened just upstream, with the royal family at Kew Palace nearby.[59]

Bedford Park

The Bedford Park neighbourhood was described by Nikolaus Pevsner as the first place "where the relaxed, informal mood of a market town or village was adopted for a complete speculatively built suburb".[60] In 1877 the speculator Jonathan Carr hired Shaw as his estate architect. Shaw's house designs, in the Queen Anne Revival style with red brick, roughcast, decorative gables, and both oriel and dormer windows, gave the impression of great variety using only a few types of house.[61] These were scaled-down versions of the more expensive houses that he had designed for wealthy areas such as Chelsea, Hampstead, and Kensington. He also designed the focal buildings of the garden suburb, including the church of St Michael and All Angels and the Tabard Inn opposite it.[60][62][63]

Duke's Meadows

Duke's Meadows stands on land formerly owned by the Duke of Devonshire. In the 1920s, it was purchased by the local council, who developed it as a recreational centre. A promenade and bandstand were built, and the meadows are still used for sport with a rugby club, football pitches, hockey club, several rowing clubs and a golf club. In recent years a local conservation charity, the Dukes Meadows Trust, has undertaken extensive restoration work, which saw a long-term project of a children's water play area opened in August 2006.[64]

Gunnersbury Triangle

The Gunnersbury Triangle local nature reserve, opposite Chiswick Park Underground station, is managed by London Wildlife Trust. The area, a railway triangle, was saved from development by a public inquiry, and became a reserve in 1985. Its 2.5 hectares are covered mainly in secondary birch woodland, with willow carr (wet woodland) in the low-lying centre, and acid grassland on the former Acton Curve railway track. The reserve runs a varied programme of activities including wildlife walks, fungus forays, open days and talks.[65][66][67]

Public houses and theatres

There are several historic public houses in Chiswick, some of them listed buildings, including the Mawson Arms,[68] the George and Devonshire,[69] the Old Packhorse[70] and The Tabard in Bath Road near Turnham Green station. The Tabard is known for its William Morris interior and its Norman Shaw exterior; it was built in 1880.[71] Three more pubs are in Strand-on-the-Green, fronting on to the Thames river path.[72]

Chiswick had two well-known theatres in the 20th century.[73] The Chiswick Empire (1912 to 1959) was at 414 Chiswick High Road. It had 2,140 seats,[74] and staged music hall entertainment, plays, reviews, opera, ballet and an annual Christmas pantomime. The Q Theatre (1924 to 1959) was a small theatre opposite Kew Bridge station. It staged the first works of Terence Rattigan and William Douglas-Home, and many of its plays went on to the West End.[75]

The 96-seat Tabard Theatre (1985) in Bath Road, upstairs from the Tabard pub but a separate business, is known for new writing and experimental work.[76]

Other buildings

The Sanderson Factory in Barley Mow Passage, now known as Voysey House, was designed by the architect Charles Voysey in 1902. It is built in white glazed brick, with Staffordshire blue bricks (now painted black) forming horizontal bands, the plinth, and surrounds for door and window openings, and dressings in Portland stone. It was originally a wallpaper printing works, now used as office space. It is a Grade II* listed building. It faces the main factory building and was once joined to it by a bridge across the road. It was Voysey's only industrial building, and is considered an "important Arts and Crafts factory building".[77]

In 1971 Erin Pizzey established the world's first domestic violence refuge at 2 Belmont Terrace, naming her organisation "Chiswick Women's Aid". The local council attempted to evict Pizzey's residents, but were unsuccessful and she soon established more such premises elsewhere, inspiring the creation of refuges worldwide.[78][79]

Chiswick is home to the Arts Educational Schools in Bath Road.[80]

The house used for filming the comedy show Taskmaster, a former groundskeeper's cottage, is just off Great Chertsey Road, near Chiswick Bridge.[81]

Transport

Chiswick is situated at the start of the North Circular Road (A406), South Circular Road (A205) and the M4 motorway, the latter providing a direct connection to Heathrow Airport and the M25 motorway. The Great West Road (A4) runs eastwards into central London via the Hogarth Roundabout where it meets the Great Chertsey Road (A316) which runs south-west, eventually joining the M3 motorway.[83]

The southern border of Chiswick runs along the River Thames, which is crossed in this area by Barnes Railway and Foot Bridge, Chiswick Bridge, Kew Railway Bridge and Kew Bridge. River services between Westminster Pier and Hampton Court depart from Kew Gardens Pier just across Kew Bridge.[84]

Bus routes on or near Chiswick High Road are the 94, 110, 237, 267, 272, 440, E3 and H91.[85] The 94 is a 24-hour service, and the High Road is also served at night by the N9.[86][87]

The District line serves Chiswick with four London Underground stations, Stamford Brook, Turnham Green, Chiswick Park and Gunnersbury.[88] Turnham Green is an interchange with the Piccadilly line, but only before 06:50 and after 22:30, when Piccadilly line trains stop at the station. Chiswick railway station on the Hounslow Loop Line is served by a regular South Western Railway service to London Waterloo via Clapham Junction.[88] The North London line crosses Chiswick (north-south); London Overground stations are Gunnersbury and South Acton.[88]

Sports

Chiswick's local rugby union teams include Chiswick RFC, formerly Old Meadonians RFC. The team plays league games on a Saturday at Dukes Meadows.[89] Chiswick's cricket club, formerly known as Turnham Green and Polytechnic, plays at Riverside Drive.[90] On Chiswick Common is the Rocks Lane Multi Sports Centre, where there are tennis, five-a-side football and netball courts available to hire to the public.[91] Private tennis coaching for individuals and groups is also available.[92]

The Chiswick reach of the Thames is heavily used for competitive and recreational rowing. Championship Course from Mortlake to Putney runs past Chiswick Eyot and Duke's Meadows. The Boat Race is contested on the Championship Course on a flood tide (in other words from Putney to Mortlake) with Duke's Meadows a popular view-point for the closing stages of the race. The finishing post is just downstream of Chiswick Bridge.[93] Other important races such as the Head of the River Race race the reverse course, on an ebb tide.[94] Chiswick is home to several clubs. The University of London Boat Club is based in its boathouse off Hartington Road, which also houses the clubs of many London colleges and teaching hospitals; recent members include Tim Foster, Gold medallist at the Sydney Olympics and Frances Houghton, World Champion in 2005, 2006 and 2007.[95] Quintin Boat Club lies between Chiswick Quay Marina and Chiswick Bridge.[96] Tideway Scullers School is just downriver of Chiswick Bridge; its members include single sculling World Champion Mahé Drysdale and Great Britain single sculler Alan Campbell.[97]

Chiswick High Road was once home to the Chequered Flag garage and its associated motor racing team.[98][99]

Notable people

18th century

In the 18th century, the poet Alexander Pope, author of The Rape of the Lock, lived in Chiswick between 1716 and 1719, in the building which is now the Mawson Arms at the corner of Mawson Lane.[100][101] The actor Charles Holland was born in Chiswick in 1733.[102] The artist William Hogarth bought the house now known as Hogarth's House in 1749,[103][104] lived there until his death in 1764, and is buried in St Nicholas's churchyard.[105][106] The house later belonged to the poet and translator of Dante, Henry Francis Cary, who lived there from 1814 to 1833.[107] In February 1766 Jean-Jacques Rousseau lived a few weeks with a local grocer, before moving to Wootton, Staffordshire.[108] The painter Johann Zoffany lived on Strand-on-the-Green.[109]

19th century

In the 19th century, the Italian writer, revolutionary and poet Ugo Foscolo died in exile at Turnham Green in 1827,[110] and was buried at St Nicholas Churchyard, Chiswick, where his monument incorrectly states he was 50, not 49. In 1871 his remains were taken to Italy and given a national hero's burial in Santa Croce, Florence alongside Michelangelo and Galileo, while his monument in Chiswick was lavishly refurbished.[111][112]

The inventor of the electric telegraph, Francis Ronalds, lived on Chiswick Lane from 1833 to 1852.[113] Another engineer, John Edward Thornycroft was born in Chiswick in 1872;[114] his father, John Isaac Thornycroft, had founded the Chiswick-based John I. Thornycroft & Company shipbuilding company in 1864, which Thornycroft later joined and developed.[115] The artist Montague Dawson, regarded as one of the best 20th-century painters of the sea, was born in Chiswick in 1895.[116]

The painter Vincent van Gogh spent three years in Chiswick in the 1870s, teaching Sunday school pupils in the newly-constructed Chiswick Congregational Church, which was on the site of the Arlington Park Mansions on Turnham Green; he wrote of Chiswick as a "verdant" district of London.[118][119][117]

The poet W. B. Yeats lived in Woodstock Road as a boy from 1879, and came back in 1887 to live in Blenheim Road, where, inspired by Chiswick Eyot, he wrote The Lake Isle of Innisfree.[120][121]

The Pissarro family of painters, the impressionist Camille Pissarro, his eldest son Lucien, as well as Felix and Ludovic-Rodo lived in 62 Bath Road, Chiswick around 1897; with Camille Pissarro painting a series of notable landscapes of the area.[122][123] The landscape artist Lewis Pinhorn Wood lived at Homefield Road[124] from 1897 to 1908.

20th century

In the twentieth century, the novelist E. M. Forster (1879–1970) lived at 9 Arlington Park Mansions[125] from 1939 until at least 1961.[126] John Osborne (1929–1994) wrote his play Look Back in Anger on his houseboat at Cubitts Yacht Basin.[127]

Notable people born before the Second World War include the cricketers Patsy Hendren (1899–1962)[128] and Jack Robertson (1917–1996),[129] the novelist Iris Murdoch (1919–1999) who lived on Eastbourne Road,[130] the theatre and film director Peter Brook (1925–2022),[131][132] the Winchester College headmaster John Leonard Thorn (1925–2023),[133] the zoologist and broadcaster Aubrey Manning (1930–2018),[134] and marine geologist Frederick Vine (1939– ).[135] The comic song performer Michael Flanders (1922–1975) spent the last years of his life in Bedford Park.[136] The actress Sylvia Syms (1934–2023), star of films such as Ice Cold in Alex, lived on Dukes Avenue.[137] The Who rock musicians John Entwistle (1944–2002) and Pete Townshend (1945– ) were both born in Chiswick during the Second World War.[138] Deep Purple lead singer Ian Gillan was born in Chiswick on 19 August 1945.[139]

Those born in Chiswick during the post-war period include the rock musician Dave Cousins,[140] the cricketer Mike Selvey (1948– ),[141] the musician Phil Collins (1951– ),[142] the singer Kim Wilde (1960– ),[143] illustrator Clifford Harper (1949– ), the photographer Derek Ridgers (1952– ),[144] actress Kate Beckinsale (1973– ),[145] the comedian Mel Smith (1952–2013),[146] and the cricketer Dimitri Mascarenhas (1977– ).[147]

Among those who have lived in Chiswick are the novelist Anthony Burgess (1917–1993), at 24 Glebe Street in the mid-1960s;[148] the playwright Harold Pinter (1930–2008) who lived at 373 Chiswick High Road;[130] the pianist and broadcaster Sidney Harrison (1903–1986) who in the 1960s lived at 57 Hartington Road[149] and later at 37 The Avenue;[150] the musical double act Bob and Alf Pearson, Bob (1907–1985) on Netheravon Road in the 1940s,[151] and Alf (1910–2012) on Linden Gardens in the 1950s;[152] the pop artist Peter Blake (1932–), in Chiswick since 1967,[153] with a "vast" studio in a former ironmonger's warehouse;[154] the actor Hugh Grant (1960– ), who grew up in Chiswick, living next to Arlington Park Mansions on Sutton Lane; the singer Bruce Dickinson (1958– ) of the band Iron Maiden;[155] the TV presenter Kate Humble (1968– );[156] the actress Elizabeth McGovern (1961– ) and her husband, film director Simon Curtis (1960– );[157] the American lawyer John Lowenthal (1925–2003),[158][159] the singer Lonnie Donegan,[140] the musician and songwriter Noel Gallagher (1967–),[160] and the model Cara Delevingne (1992– ).[161]

21st century

The playwright Michael Frayn (1933– ) and his daughter the film maker and novelist Rebecca Frayn live in Chiswick.[162] Chiswick residents have included the singer Sophie Ellis-Bextor,[163] the TV journalists Jeremy Vine,[163] Rageh Omaar[163] and Fergal Keane,[163] the actors Phyllis Logan,[163] Colin Firth,[163] David Tennant, Georgia Tennant,[164] and Vanessa Redgrave,[165] the TV presenters Clare Balding,[161] Sarah Greene,[163] Gavin Campbell,[163] and Mary Nightingale,[163] the journalist Alice Arnold,[163] and the celebrity duo Anthony McPartlin and Declan Donnelly.[166]

Demography and housing

| Ward | Detached | Semi-detached | Terraced | Flats and apartments | Caravans etc. | Shared[2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chiswick Homefields | 149 | 916 | 1218 | 2493 | 12 | 69 |

| Chiswick Riverside | 243 | 947 | 1136 | 2753 | 3 | 25 |

| Turnham Green | 179 | 675 | 1247 | 2423 | 2 |

| Ward | Population | Households | % Owned outright | % Owned w. loan | hectares[2] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chiswick Homefields | 11346 | 4857 | 25.8 | 28.1 | 203 |

| Chiswick Riverside | 11543 | 5107 | 24.8 | 31 | 192 |

| Turnham Green | 11448 | 5443 | 25.9 | 23.5 | - |

In the arts

The novel Vanity Fair (1847/8) by William Makepeace Thackeray opens at Miss Pinkerton's Academy for Young Ladies in Chiswick Mall. Louis N. Parker's play Pomander Walk (1910) has the imagined setting of "a retired crescent of five very small, old-fashioned houses near Chiswick, on the river-bank. ... They are exactly alike: miniature copies of Queen Anne mansions".[167] Ford Madox Ford's Parade's End tetralogy (1924/28) contains many scenes set in Chiswick, where the Wannop family resides. The BBC adaptation of the literary work featured filming on Bedford Park's Woodstock Road.[168] Basil Dearden's 1961 suspense film Victim, starring Dirk Bogarde as the barrister Melville Farr, was set in Chiswick, and many of its scenes were filmed on Chiswick Mall, where Farr lived.[169] On May 20, 1966 the Beatles filmed two of their earliest promotional films for the songs "Paperback Writer" and Rain in the grounds of Chiswick House.[170] The BBC sitcom My Family was set in Chiswick; it ran from 2000 to 2011.[171]

Nearest places

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ Census Information Scheme (2012). "2011 Census Ward Population figures for London". Greater London Authority. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- 1 2 3 http://neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk Key Statistics; Quick Statistics: Population Density [1] Office for National Statistics

- ↑ "How Do You Pronounce Theydon Bois?". Londonist. 17 October 2011. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- ↑ Room, Adrian (1988). Dictionary of Place-Names in the British Isles. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9780747501701.

- ↑ "Plea Rolls of the Court of Common Pleas. CP 40/629; Year 1418". National Archives. pp. third entry – Chesewyk is the home of John Meryman, carpenter, a defendant.

- ↑ Baker 1982, Growth.

- 1 2 Clegg 1995, p. 17.

- ↑ Clegg 1995, pp. 29–30.

- 1 2 Clegg 1995, p. 38.

- ↑ Arthure, Humphrey (n.d.). Thornycroft Shipbuilding and Motor Works in Chiswick. p. 24.

- ↑ Arthure, Humphrey (March 1982). Life and Work in Old Chiswick.

- ↑ Lyon, David (1996). The First Destroyers. Caxton Editions. pp. 40–41. ISBN 1-84067-364-8.

- ↑ Clegg 1995, pp. 87–88.

- ↑ Elliot, Brent (2004). The Royal Horticultural Society: A History 1804–2004. Royal Horticultural Society.

- ↑ "Chiswick St Nicholas CP/AP through time | Population Statistics | Total Population". Visionofbritain.org.uk. Retrieved 26 November 2010.

- ↑ Roe, William P. (1999). Glimpses of Chiswick's Development. W. P. Roe. pp. 80–90. ISBN 978-0951651223.

- ↑ Rincon, Paul (7 September 2004). "V-2: Hitler's Last Weapon of Terror". BBC News.

- ↑ "Chiswick – From Ramshackle Fishing village to a Leafy and Affluent Suburb". Thorgills. Archived from the original on 26 April 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ↑ Draper, Warwick (1990). Chiswick. Anne Bingley and Hounslow Leisure Services. pp. 173, 176.

- ↑ Great Britain Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth, Chiswick parish (historic map). Retrieved {{{accessdate}}}. Archived 24 December 2012 at archive.today

- ↑ Higginbotham, Peter. "The Workhouse, the story of an institution. Brentford, Middlesex". Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Logan, Tracey (2016). Improving Chiswick, 1858–1883. SAS-Space (masters). University of London School of Advanced Study. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- 1 2 Chiswick: Growth, A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 7: Acton, Chiswick, Ealing and Brentford, West Twyford, Willesden, (1982). Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ↑ Great Britain Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth, Chiswick UD (historic map). Retrieved {{{accessdate}}}.

- ↑ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 247.

- ↑ Great Britain Historical GIS / University of Portsmouth, Brentford and Chiswick UD/MB (historic map). Retrieved {{{accessdate}}}. Archived 18 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "London Government Act 1963". Legislation.co.uk. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- ↑ "Approved premises and licensing venues for ceremonies". London Borough of Hounslow. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ↑ "The Parliamentary Constituencies (England) Order 1970". www.legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 4 November 2019.

- ↑ "Chiswick Homefields election result 2010". London Borough of Hounslow. Archived from the original on 10 May 2010. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ↑ "Chiswick Riverside election result 2010". London Borough of Hounslow. Archived from the original on 10 May 2010. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ↑ "Turnham Green election result 2010". London Borough of Hounslow. Archived from the original on 10 May 2010. Retrieved 7 May 2010.

- ↑ Mayor of London (February 2008). "London Plan (Consolidated with Alterations since 2004)" (PDF). Greater London Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2010.

- ↑ Clegg 1995, p. 63.

- ↑ Hounslow London Borough Council – Map of Hounslow Archived 28 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 1 February 2008.

- ↑ Clegg, Gillian (2003). "The Glebe Estate, Chiswick". Brentford & Chiswick Local History Society. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ↑ "The Postcodes Project: W4 Chiswick". Museum of London. Archived from the original on 8 July 2007. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ↑ Chiswick: Economic history, A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 7: Acton, Chiswick, Ealing and Brentford, West Twyford, Willesden (1982), pp. 78–86. Retrieved on 1 February 2008.

- ↑ map in Chiswick Past, page 123

- ↑ Clegg 1995, p. 137.

- ↑ "Who organises the Chiswick Book Festival?". The Chiswick Calendar. Retrieved 26 October 2022.

- ↑ "History and Heritage". Fuller's. Archived from the original on 26 June 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2015.

- ↑ "The Food Market Chiswick". Duke's Meadows Trust. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ↑ "Chiswick Flower Market". Chiswick Flower Market. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ↑ "New application for cheese and provisions market submitted". Chiswick W4. 12 December 2020. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ↑ "Chiswick Cheese Market". Chiswick Cheese Market. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ↑ "Chiswick House and Gardens". Chiswick House & Gardens Trust. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ↑ "The History of Chiswick House Asylum". Bethlem Museum of the Mind. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

- ↑ "Thomas Scheemakers". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 2014. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014.

- 1 2 Clegg, 1995. p 30

- ↑ "Parade planned for Chiswick's Rorke's Drift Hero". Chiswick W4. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- 1 2 3 "A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 7, Acton, Chiswick, Ealing and Brentford, West Twyford, Willesden". British History. pp. 90–93.

- ↑ "A brief history of the Church". St Michael and All Angels. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ↑ "Roman Catholic Church of Our Lady of Grace & St Edward: Parish History". Diocese of Westminster. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ↑ Jeffery, Paul (2012). England's other cathedrals. Stroud, UK: History Press. ISBN 9780752490359.

- 1 2 Clegg, Gill (2021). "Grand Houses". Brentford & Chiswick Local History Society. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ↑ Hounslow (November 2018). Old Chiswick: Conservation Area Appraisal: Consultation Draft (PDF). London Borough of Hounslow. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 December 2020.

- ↑ "Walpole House". Historic England. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- 1 2 3 "Strand on the Green Conservation Area Appraisal" (PDF). London Borough of Hounslow. May 2018. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 June 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- 1 2 Cherry & Pevsner 1991, pp. 406–410.

- ↑ Clegg, Gillian. "People". Brentford & Chiswick Local History Society. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ↑ Girouard, Mark (1984) [1977]. Sweetness and Light: The Queen Anne Movement, 1860–1900. Yale University Press. pp. 160–176. ISBN 978-0-300-03068-6.

- ↑ "Bedford Park, Ealing". Hidden London. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- ↑ "About Us". Dukes Meadows Trust. Archived from the original on 5 February 2014. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ↑ "Gunnersbury Triangle". Local Nature Reserves. Natural England. 18 December 2013. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ↑ "Map of Gunnersbury Triangle". Local Nature Reserves. Natural England. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- ↑ "Gunnersbury Triangle". London Wildlife Trust. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ↑ Historic England. "Ye Fox And Hounds And Mawson Arms And Nos. 112–118 (1358692)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ↑ Historic England. "The George And Devonshire Arms Public House (1358664)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ↑ Historic England. "The Old Packhorse Public House (1240781)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ↑ Historic England. "Tabard Hotel public house (1079594)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- ↑ "Conservation Areas" (PDF). Hounslow London Borough Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2007. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ↑ Clegg 1995, pp. 95–97.

- ↑ Looby, Patrick (1997). Britain in Old Photographs, Chiswick & Brentford. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-1151-4.

- ↑ Roe, Ken. "Q Theatre". Cinema Treasures. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ↑ Tabard Theatre – History Archived 19 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 20 August 2010.

- ↑ "Voysey House, Hounslow". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ↑ "Pizzey calls for more domestic abuse shelters". Richmond and Twickenham Times. 12 May 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ↑ "Battered? Erin Pizzey? Yes, a bit". The Independent. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- ↑ "Arts Educational Schools London". Arts Educational Schools London. 2014. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ "Where is the Taskmaster house? You can actually visit the filming location". Radio Times. 18 March 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- ↑ Country Life, 8 July 1933, quoted in Cookson, Brian (2006), Crossing the River, Edinburgh: Mainstream, p. 69, ISBN 1-84018-976-2, OCLC 63400905

- ↑ "Chiswick Area Map" (PDF). Hounslow Borough Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 September 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ↑ "Thames River Boats". WPSA. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ↑ "Buses from Hammersmith" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 December 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ↑ "Buses from Marble Arch" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 February 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- ↑ "Night Buses from Hammersmith" (PDF). Transport for London. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 May 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- 1 2 3 "Chiswick Area Guide". Ludlow Thompson. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ↑ "Chiswick Rugby Football Club". Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ↑ "Welcome to Chiswick Cricket Club". Chiswick Cricket Club. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ↑ "Rocks Lane Chiswick". OpenPlay. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ↑ "Rocks Lane Chiswick Tennis Coaching". TennisTeach. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ↑ "The Course". The Boat Race. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ↑ "The Head of the River Race". Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ↑ "University of London Boat Club". ULBC. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ↑ "Quintin Boat Club". Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ↑ "Tideway Scullers". Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ↑ "The Chequered Flag, A Brief History". The Historic Racing and Sports Car Club. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ↑ "At the Sign of the Chequered Flag". Motor Sport (May 1960): 29. May 1960.

- ↑ Fisher, Lois H. (1980). A literary gazetteer of England. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780070210981.

Mawson Arms Alexander Pope.

- ↑ "Start or finish your Brewery Tour with lunch at the Mawson Arms". fullers.co.uk. Archived from the original on 28 June 2014. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ Highfill, Philip H.; Burnim, Kalman A.; Langhans, Edward A. (1982). A Biographical Dictionary of Actors, Actresses, Musicians, Dancers, Managers & and Other Stage Personnel in London: 1660–1800, Volume 7. SIU Press. ISBN 978-0809309184.

- ↑ "Hogarth's House | Hounslow.info". hounslow.info. Archived from the original on 27 October 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ Taylor, Joel (11 March 2005). "Camden New Journal". camdennewjournal.co.uk. Archived from the original on 5 February 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ "St Nicholas Chiswick – The Churchyard". stnicholaschiswick.org. Archived from the original on 5 July 2013. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ Cherry & Pevsner 1991, p. 404.

- ↑ Kennedy, Maev (7 November 2011). "Hogarth's house to reopen after surviving fire – and urban sprawl". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ "Chronologie de Jean-Jacques Rousseau". www.rousseau-chronologie.com. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ↑ "Johann Zoffany (1733-1810)". The Chiswick Calendar. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ↑ Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Review Volume 97, Part 2. 1827. pp. 566–569. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ Bentley's Miscellany. J. M. Lewer. 1839. p. 603. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ Riall, Lucy (2007). Garibaldi : invention of a hero. Yale University Press. p. 4.

- ↑ Ronalds, B.F. (2016). Sir Francis Ronalds: Father of the Electric Telegraph. Imperial College Press. pp. 48–49. ISBN 978-1-78326-917-4.

- ↑ "Sir John E Thornycroft". heritage.imeche.org. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- ↑ Humphrey Arthure: "Thornycroft Shipbuilding and Motor Works in Chiswick".

- ↑ "Montague Dawson on artnet". artnet.com. artnet. Retrieved 21 May 2013.

- 1 2 Clegg, Gillian (2001). "Van Gogh In Chiswick". Brentford and Chiswick Local History Society. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ↑ "Wall Street Journal Tells Readers to Pay a Visit to Chiswick: Describes it as a lush paradise that inspired Van Gogh". Chiswick W4. 2 July 2023. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

- ↑ Longworth, Mary Lou (29 June 2023). "Visiting London? Don't Skip Chiswick, a Lush Paradise that Inspired Van Gogh, W.B. Yeats and More". Wall Street Journal.

More than pretty gardens draw people to this leafy suburb. The other lures: trendy gastropubs, cheese toasties and the haunting traces of centuries of artists and writers.

- ↑ "Chiswick Statue Planned To Honour WB Yeats". ChiswickW4.com. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ↑ "Yeats in Bedford Park". ChiswickW4.com. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ↑ Reed, Nicholas (1997). Pissarro in West London: Kew, Chiswick and Richmond. Lilburne Press. pp. 30–35. ISBN 9781901167023. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ↑ Seaton, Shirley (2013). "Camille Pissarro: Paintings of Stamford Brook, 1897 | Brentford & Chiswick Local History Society". brentfordandchiswicklhs.org.uk. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ↑ "Lewis Pinhorn WOOD (exhibited 1870 – 1913)". Arrival of a Steamer at the Old Kew Bridge. Elford Fine Art. Archived from the original on 1 March 2014. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ↑ Moffat, Wendy (2011). E. M. Forster: A New Life. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781408824276.

- ↑ "E.M. Forster 9 Arlington Park Mansions, Sutton Lane, Chiswick, London". Notable Abodes. 2011. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ↑ "Writers Trail". Chiswick Book Festival. 2021. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ↑ "Patsy Hendren". ESPN Sports Media. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ↑ "Jack Robertson". ESPN Sports Media. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- 1 2 "Iris Murdoch Deemed Top Pick for Next Chiswick Blue Plaque". Chiswick W4. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ↑ Aronson, Arnold (25 May 2005). "Peter Brook: A Biography". The New York Times.

- ↑ Kustow, Michael (17 October 2013). Peter Brook: A Biography. A&C Black. pp. 5–7. ISBN 978-1-4088-5228-6. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ↑ "John Thorn, visionary headmaster who steered Winchester through the tumultuous late 1960s and 1970s – obituary". The Daily Telegraph. 1 November 2023. Retrieved 1 November 2023.

- ↑ "OU on the BBC: Rules of Life – Meet Aubrey". Open University. 24 October 2005. Archived from the original on 29 July 2018. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ↑ "Oral History of British Science: Vine, Fred". British Library. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ↑ "Flanders, Michael". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/31113. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ "Dukes Avenue Resident Sylvia Syms Dies Aged 89: Actress had career in stage, film and TV spanning six decades". Chiswick W4. 28 January 2023. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ↑ Giuliano, Geoffrey (2002). Behind Blue Eyes: The Life of Pete Townshend. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 278. ISBN 978-0815410706.

- ↑ Gillan, Ian; Cohen, David (1993). Child in Time: The Life Story of the Singer from Deep Purple. Smith Gryphon. p. 2. ISBN 1-85685-048-X.

- 1 2 "Rock Legend to Share Memories of Growing Up in Chiswick". Chiswick W4. 13 November 2022. Retrieved 14 November 2022.

- ↑ "Mike Selvey". ESPN Sports Media. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ↑ Davies, Hugh (25 April 2001). "Phil Collins becomes a father again at age of 50". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2014.

- ↑ "Introductory Magazine". The Official Fan Club for Kim Wilde. p. 4. Archived from the original on 10 February 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ↑ Williams, Val; Bright, Susan (2007). How We Are: Photographing Britain, from the 1840s to the Present. Tate. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-85437-7142.

- ↑ Kate Beckinsale's Chiswick Homecoming, Chiswick W4, 8 September 2003,

... to return to live in Chiswick. The 30 year old daughter ...

- ↑ Cavendish, Dominic (22 July 2006). "I'm hoping to cover my air fare". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ↑ "Dimitri Mascarenhas". ESPN Sports Media. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ↑ Biswell, Andrew (2006). The Real Life of Anthony Burgess. Picador. p. 307. ISBN 978-0-330-48171-7.

- ↑ Musical Times No 1426, December 1961, p 749 (Front Matter)

- ↑ Writers Directory, 1980-1982, p 534

- ↑ "Bob Pearson (Musician)". Notable Abodes. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ↑ "Alf Pearson (Musician)". Notable Abodes. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ↑ Nikkhah, Roya (20 November 2016). "Sir Peter Blake: why I chose Pop over pot". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ↑ Barber, Lynn (17 June 2007). "Blake's progress". The Guardian.

- ↑ Keaveny, Shaun (2010). R2d2 Lives In Preston. Pan Macmillan. p. 11. ISBN 9780752227450. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ↑ Swinford, Steven (21 April 2013). "Kate Humble: I lived in a squat and took drugs". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ↑ Gilbert, Gerard (18 December 2010). "'Hollywood never suited me': Elizabeth McGovern on fleeing LA and Downton Abbey's Lady Cora". The Independent. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- ↑ Lowenthal, John (2 July 1999). "Venona and Alger Hiss". Times Literary Supplement. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ↑ Lowenthal, John (13 August 1999). "Views of Alger Hiss". Times Literary Supplement.

- ↑ Horton, Matthew (24 April 2013). "18 Things You Might Not Know About Oasis's 'Some Might Say'". NME. Retrieved 3 January 2023.

- 1 2 "Supermodel set to move to Chiswick". ChiswickW4. 24 November 2014. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ↑ "Rebecca Frayn's Deceptions". Chiswick W4.com. 10 June 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Sophie Ellis Bextor Sings At 50th Green Days Festival. Chiswick celebrities also joined the line-up for the opening event". Chiswick W4.com. 10 June 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ↑ Hunt, Elle (8 July 2020). "'We're not squeamish!' David Tennant on privacy, parenting and playing himself". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ↑ "Damehood for Vanessa Redgrave in New Year's Honours: Chiswick-based actor and activist 'surprised' at award". Chiswick W4. 4 January 2022. Retrieved 5 January 2022.

- ↑ Bhandari, Serena (13 November 2017). "Ant McPartlin 'feeling great' post-rehab". The Chiswick Herald. Retrieved 9 May 2018.

- ↑ Parker, Louis N. (1915). Pomander Walk. Samuel French. p. 13.

retired crescent.

- ↑ "Woodstock Road Goes Back in Time a Hundred Years". Chiswick W4. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ↑ "When Dirk Bogarde Filmed In Chiswick". Chiswick W4. 29 July 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ↑ "50 years since The Beatles filmed two groundbreaking music videos". Chiswick House & Gardens. 20 May 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ↑ "The End of My Family: BBC says goodbye to Chiswick's middle class Harpers after an 11 year run". Chiswick W4. 28 March 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2021.

Sources

- Baker, T. F. T.; et al. (1982). "Chiswick: Growth". A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 7: Acton, Chiswick, Ealing and Brentford, West Twyford, Willesden. British History Online.

- Clegg, Gillian (1995). Chiswick Past. Historical Publications. ISBN 0-94866-733-8.

- Cherry, Bridget; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1991). The Buildings of England. London 3: North West. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-071048-9. OCLC 24722942.

.jpg.webp)