rue de la Chaussée d'Antin with the Trinity church in the background | |

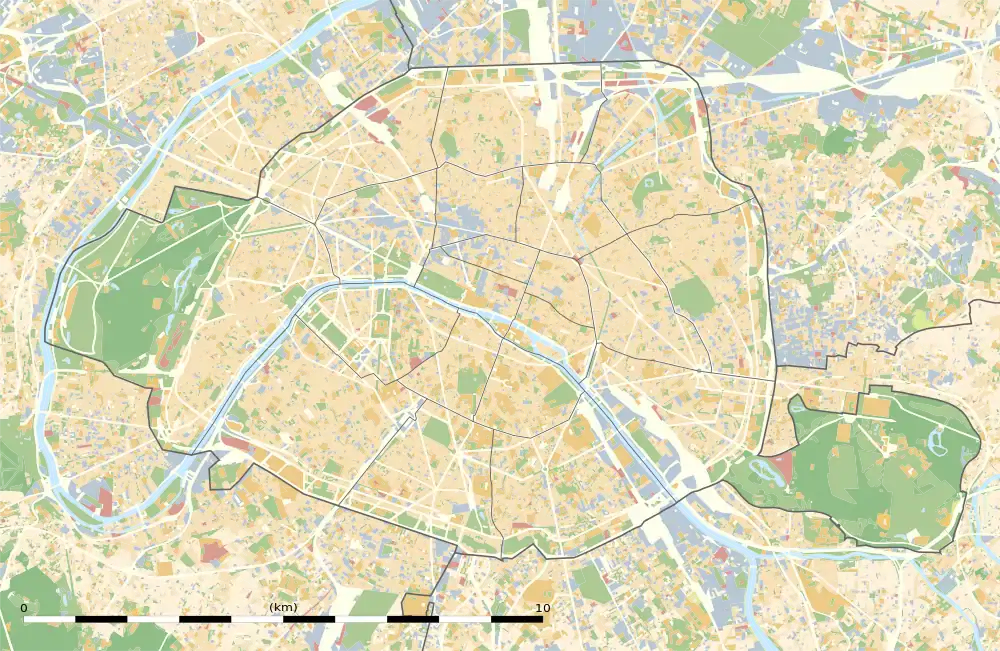

Shown within Paris | |

| Arrondissement | 9th |

|---|---|

| Quarter | Chaussée-d'Antin |

| Coordinates | 48°52′26″N 2°19′58″E / 48.87389°N 2.33278°E |

| From | 2 Boulevard des Capucines |

| To | 73 Rue Saint-Lazare |

| Construction | |

| Denomination | 1712 |

| Located near the Métro stations: Chaussée d'Antin - La Fayette and Trinité - d'Estienne d'Orves. |

This "quartier" of Paris got its name from the rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin in the 9th arrondissement of Paris.[1] It runs north-northwest from the Boulevard des Italiens to the Église de la Sainte-Trinité.

In the 17th century the chemin des Porcherons crossed a swampy piece of ground north of the porte Gaillon, a city gate in the wall built during the reign of Louis XIII, leading to the village of Les Porcherons. It is called a chaussée because the marshy ground required raised construction that ran along the top of a sort of dyke.

At the rue de Provence it crossed the "great sewer" or Ruisseau de Ménilmontant, which was approximately two meters wide.

Under an ordinance dated 4 December 1720, the street was graded and resurveyed as a wider boulevard with a width of eight toises and extended to meet the grands boulevards to the south. This new boulevard stretched from the end of Rue Louis-le-Grand to Rue Saint-Lazare.

The frequent stays of Louis XV in Paris led to the building of splendid homes such as that of Louis Antoine de Pardaillan de Gondrin, the Duke of Antin (1665–1736). Son of the marquise de Montespan, the duke was the superintendent of the Bâtiments du Roi, or buildings of the king. His residence[2] faced this street and his name became associated with it as early as 1712.

Notable places

At the intersection of the Boulevard des Capucines, stood the former hôtel de Montmorency, which gave way to the Théâtre du Vaudeville in 1869, and then the Paramount Opéra cinema theater in 1927. The main hall of the theater corresponds to the 'grand salon' -- probably a ballroom—of the 18th-century hôtel. The rotunda above the facade has been preserved.

The notorious Cabaret de la Grande Pinte stood on the present site of the Église de la Sainte-Trinité. It opened in 1724, and could accommodate 600 people for public festivities.

At the intersection of the Boulevard des Italiens stood the barracks of the Gardes Françaises - a regiment of the royal guard which was to play a key role in the revolutionary events of July 1789. The barracks was built by the Duke of Biron in 1764. It gave the boulevard its name for some years. On 12 July 1789, a platoon of the French Guards saved its colonel, M. Duchâtelet, from popular riots. [3]

The air was thought to be healthier to the north and west of Paris during the 18th century. That, and the higher ground, attracted the upper classes. A series of glamorous hôtels particuliers were erected along the Chaussée-d'Antin in the later 18th century (now destroyed) :

.JPG.webp)

- At n°1 (exactly on the corner with Boulevard des Capucines) and n°3 were the entrances of hôtel de Montmorency.

- At n°5, hôtel of Madame d'Epinay and the baron Grimm who was living with her. They hosted Mozart for a couple of months in 1778 after the death of his mother. The street's most famous resident, Frédéric Chopin, also lived here from 1833 to 1836, most of the time together with his very close friend Jan Matuszyński.[5] Frequent visitors included Franz Liszt.

- At n°9, the hôtel of mademoiselle Guimard, who made her reputation as a dancer at the Opéra, where she earned 600 livres a year. She made her fortune however as the mistress of the prince de Soubise, and lived in an advanced Neoclassical building erected for her by Claude-Nicolas Ledoux in 1770-73. It was dubbed the "temple of Terpsichore crowned by Apollo", a reference to Mlle Guimard. The building had a 500-seat theater which rivalled the Opéra. Later in life Mlle Guimard raffled off her hôtel, selling 2,500 tickets at 120 livres each.

- At n°20, hôtel of general Moreau where the coup d'état of 18 Brumaire was planned. In 1977, 400 pieces of sculpture, from the facade of the cathedral Notre Dame de Paris, were found underground of the hôtel Moreau. Especially heads of the kings of Judea. During the French Revolution, the statues were destroyed because people thought that they were statues of kings of France.

- Frédéric Chopin lived at no. 38 from 1836 to 1838, together with another old friend Julian Fontana, who acted as his doctor-in-residence and factotum,[5] after moving from no. 5 rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin.

- At n°46, hôtel of Mirabeau, where he died on 2 April 1791 after a plentiful dinner. It gave the Chaussée the Revolutionary name of rue de Mirabeau from 1791 until, with Mirabeau proscribed in 1793, it was renamed rue du Mont-Blanc in celebration of a commune that had been added to French territory. It regained its former name in 1815.

- At n°62, hôtel of Maximilien Sébastien Foy, where he died on 28 November 1825.

- At n°70, hôtel of Cardinal Fesch, the archbishop of Lyon and uncle of Napoleon.

- At the corner with rue de la Provence stood the hôtel of the Duc d'Orléans, and next door that of his wife Madame de Montesson. They had a private chapel and a theater. The duke's secretary baron Grimm is supposed to have lived in one of his apartments.

During the 19th century commercial establishments changed the character of the street, and shops opened in the ground floors of the old residences. For Honoré de Balzac "The heart of Paris today beats between rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin and rue du Faubourg Montmartre." In 1840 the street was extended past rue Neuve-Saint-Augustin. The first one-way streets in Paris were the Rue de Mogador and the Rue de la Chaussée-d'Antin, created on 13 December 1909.

Notes

- ↑ Quartier de la Chaussée-d'Antin

- ↑ Later the hôtel de Richelieu, Paris seat of the duc de Richelieu.

- ↑ Le boulevard des Italiens on the web site paris-pittoresque.com

- ↑ "La chaussée d'Antin - Atlas historique de Paris".

- 1 2 Walker, Alan, 1930-. Fryderyk Chopin : a life and times (First ed.). New York. pp. 296f. ISBN 978-0-374-15906-1. OCLC 1005818033.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

References

- Louis Lurine, ed. 1844 Les rues de Paris. Paris ancien et moderne

External links

- (in French) Histoire de Paris rue par rue, maison par maison, Charles Lefeuve, 1875

- (in English) Thirza Vallois, Paris Kiosque: the 9e Arrondissement