Charles A. Willoughby | |

|---|---|

Charles Andrew Willoughby | |

| Birth name | Adolf Karl Tscheppe-Weidenbach |

| Nickname(s) | 'Sir Charles' |

| Born | March 8, 1892 Heidelberg, German Empire |

| Died | October 25, 1972 (aged 80) Naples, Florida |

| Place of burial | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1910–1952 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | World War I World War II Korean War |

| Awards | Distinguished Service Cross Distinguished Service Medal (3) Silver Star |

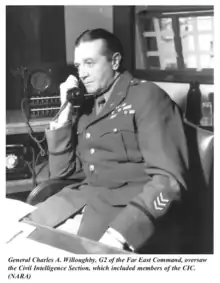

Charles Andrew Willoughby (March 8, 1892 – October 25, 1972) was a major general in the U.S. Army, serving as General Douglas MacArthur's chief of intelligence during most of World War II and the Korean War.

Early life and education

Willoughby is often quoted as being born March 8, 1892, in Heidelberg, Germany, as Adolph Karl Weidenbach, the son of Baron T. Tscheppe-Weidenbach and wife Emma Willoughby Tscheppe-Weidenbach of Baltimore, Maryland. This was disputed by Frank Kluckhohn of The Reporter (New York Journal) in 1952, and there remains uncertainty as to both his birth name and lineage.[1]

It is certain, however, that Willoughby emigrated from Germany to the U.S. in 1910, and in October 1910 he enlisted in the U.S. Army, where he served with the 5th Infantry, initially as a private, later rising to the rank of sergeant. He was honorably discharged from the army in 1913.

He then entered Gettysburg College as a senior in 1913 based on his attestations of three years of attendance at the University of Heidelberg and the Sorbonne in Paris before he emigrated to the United States. Although he graduated with a B.A. in 1914, it is disputed whether or not he actually did attend either European university.[2][3]

After graduation from Gettysburg College, Willoughby was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Officers' Volunteer Reserve Corps of the U.S. Army in 1914. He spent three years teaching German and military studies (while serving as a reserve U.S. Army officer) at various prep-schools in the United States. In August 1916, he vacated his position in the reserve to accept a Regular Army commission as a second lieutenant under the name Adolph Charles Weidenbach. He rose to Captain and served in World War I in the American Expeditionary Force.[3]

He changed his name at some point between 1910 and 1930 to Charles Andrew Willoughby (a loose translation of Weidenbach, the German for "willow brook").[2] During his early life, he became fluent in English, Spanish, German, French, and later, Japanese.

World War I

Using the name Adolf Charles Weidenbach, Willoughby was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Regular Army on 27 November 1916, and promoted to first lieutenant on the same day.[2] He joined the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) in June 1917 and was promoted to captain (permanent) on 30 June 1917, serving initially with the 16th Infantry Regiment (United States), First Division. He later transferred to the U.S. Army Air Corps, where he was trained as a pilot by the French military.[2]

Post World War I

After the war, Captain Willoughby/Weidenbach joined the 24th Infantry in New Mexico in 1919. He spent two years at his post before being posted to San Juan, Puerto Rico. He became involved in military intelligence while in San Juan. While serving in Puerto Rico he married Juana Manuela Rodríguez Umpierre who bore him a daughter, Olga. He had served as a Military Attaché in Ecuador. He received the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus from Benito Mussolini's Fascist Italian government. In the 1920s Willoughby was an admirer of Spanish General and future dictator Francisco Franco, calling him the "second greatest general in the world". He met him in Morocco and then delivered a speech to him at a lunch in Madrid.[2] He was toasted by the Secretary General of the Falangist Party.[2]

In 1929, Willoughby was assigned to Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas as a student and in 1931 as an instructor. In 1936, Major Willoughby was promoted to lieutenant colonel.

World War II and the occupation of Japan

Willoughby was the Chief of Intelligence on General MacArthur's staff during World War II, the occupation of Japan, and the Korean War. In Australia, Willoughby was not allowed to be present at the daily intelligence briefings given to MacArthur by USN codebreaker Rudy Fabian, see Central Bureau.

Willoughby became a major general on 12 April 1945. Due to his initiative at the end of the Pacific Campaign war crimes charges against Shirō Ishii were dispensed with in exchange for information gathered by Unit 731, a covert biological and chemical warfare research and development unit of the Imperial Japanese Army that undertook lethal human experimentation in China. Additionally there was a monetary reward for Ishii.[4]

In Japan, Willoughby was assigned the head of the G-2 in Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP), which was mainly in charge of intelligence and enforcing SCAPIN-33 (Press code for Japan) for censorship of the Japanese press.[5][6] Under his administration numerous alleged Japanese war criminals such as Yoshio Kodama and Masanobu Tsuji were rehabilitated and recruited.[7]

Paranoidly anti-communist, Willoughby claimed without basis that there was a "leftist infiltration" of the GHQ, and he went out of his way to track and discredit thinkers left of himself. Willoughby investigated New Dealers in Charles Louis Kades in GHQ's Government Section, an endeavor that included blacklisting economist Eleanor Hadley such that she could not obtain a steady government job in the United States for seventeen years, and he ordered Japanese police to secretly spy on occupation officials. He even meddled in Japanese domestic politics, bringing down the Democrat–Socialist–People's Cooperative coalition government led by Hitoshi Ashida.[8] According to declassified 2005 CIA documents, Willoughby organized a group of ultranationalists including Hideaki Tojo's former secretary Takushiro Hattori in 1952 to assassinate then-prime minister Shigeru Yoshida. He was to be replaced with Ichirō Hatoyama who was much more hawkish and eager to re-militarize Japan. The plan was aborted after potential support within the National Safety Agency dried up.[9] The CIA report describes both coup members as "extremely irresponsible," Tsuji in particular is characterized as "the type of man who, given the chance, would start World War III without any misgivings."[10] According to Seagraves, Willoughby was briefed by Edward Lansdale in Tokyo about the "Golden Lily", 金の百合 (kin no yuri), 'M-Fund', or Yamashita's gold.[11][12][13]

Korean War

Willoughby's contribution during the Korean War is subject to some significant controversy, with several sources insisting that he intentionally distorted, if not out and out suppressed, intelligence estimates that showed the Chinese were massing at the Yalu River. Willoughby allegedly did so in order to better support MacArthur's (mistaken) assertion that the Chinese would never cross the Yalu, and thus allow MacArthur a freer hand in his drive to the Yalu.[14]

MacArthur affectionately referred to him as "my pet fascist."[15] Willoughby's "vitriolic, paranoid, and frequently fantastic" notes included antisemitic insults towards Beate Sirota Gordon, who helped write the Constitution of Japan.[16] During World War II MacArthur said, "There have been three great intelligence officers in history. Mine is not one of them."[17] John Ferris in his 2007 book Intelligence and Strategy calls this an "understatement" and calls Willoughby a "candidate for one of the three worst intelligence officers of the Second World War" (p. 261).

Writer David Halberstam, in his book The Coldest Winter, paints Willoughby as largely having been appointed head of intelligence for Korea due to his sycophancy toward MacArthur. He points out that many veterans of the war, both enlisted and otherwise, felt that the lack of correct intelligence regarding the Chinese presence resulted in poor preparation by field commanders. This also contributed to MacArthur's desire to push his upper level commanders to divide their commands, making mutual support of units and fortifications inadequate for the large numbers of Chinese they were about to face.

As said of Willoughby, by Lieutenant Colonel John Chiles, 10th Corps G-3, or chief of operations of that unit.[18]

MacArthur did not want the Chinese to enter the war in Korea. Anything MacArthur wanted, Willoughby produced intelligence for.… In this case Willoughby falsified the intelligence reports.… He should have gone to jail...

Other activities

Willoughby was involved in the creation of Field Operations Intelligence, a top secret Army Intelligence unit that later came under joint military and Central Intelligence Agency control.

Willoughby allegedly organized an assassination, instead of a coup d'état, against Shigeru Yoshida in early 1950s Japan involving ultranationalists Masanobu Tsuji and Takushiro Hattori.[19][9][20]

Willoughby was named by Rob Reiner ("Who Killed JFK" Podcast with Soledad O'Brien) as the master tactician of the Kennedy assassination, in collaboration with Bill Harvey.

Retirement, death and legacy

Willoughby retired from the Army on August 31, 1951. After his retirement, Willoughby travelled to Spain to act as an advisor and lobbyist for dictator Francisco Franco.[2]

In his later years, Willoughby published the Foreign Intelligence Digest newspaper, and worked closely with Texas oil tycoon H. L. Hunt on the International Committee for the Defence of Christian Culture, an extreme right "umbrella" organization that had connections to anti-communist groups.

Another one of Willoughby's allies was the Rev. Billy James Hargis.[21] In 1968, Willoughby moved with his wife to Naples, Florida.

Charles A. Willoughby died on 25 October 1972 and was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. He is a member of the Military Intelligence Hall of Fame.

Dates of rank

| Enlisted, United States Army: 10 October 1910; Discharged as Sergeant: 9 October 1913 | |

| Second lieutenant, United States Army: 27 November 1916 | |

| First lieutenant, United States Army: 27 November 1916 | |

| Captain, United States Army: 30 June 1917 | |

| Major, United States Army: 6 March 1928 | |

| Lieutenant colonel, United States Army: 1 June 1938 | |

| Colonel, Army of the United States: 14 October 1941 | |

| Brigadier general, Army of the United States: 20 June 1942 | |

| Major general, Army of the United States: 17 March 1945

(Terminated 31 May 1946) | |

| Colonel, United States Army: 1 September 1945 | |

| Brigadier general, Army of the United States: 31 May 1946

(Date of rank 20 June 1942) | |

| Brigadier general, United States Army: 24 January 1948 | |

| Major general, Army of the United States: 24 January 1948 | |

Decorations and medals

Willoughby received numerous military decorations and medals,[3] including:

| 1st Row | Distinguished Service Cross | Army Distinguished Service Medal with two Oak Leaf Clusters | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2nd Row | Silver Star | Legion of Merit | World War I Victory Medal | American Defense Service Medal | ||||||||||||||

| 2nd Row | Asiatic Pacific Campaign Medal with seven service stars | World War II Victory Medal | Army of Occupation Medal | National Defense Service Medal | ||||||||||||||

| 3rd Row | Korean Service Medal with one service star | United Nations Korea Medal | Grand Officer of the Order of Orange-Nassau (Netherlands) | Commander of the Order of Saints Maurice and Lazarus (Italy) | ||||||||||||||

| 4th Row | Distinguished Service Star (Philippines) | Philippine Defense Medal | Philippine Liberation Medal with two bronze stars | Order of Abdon Calderón (Ecuador) | ||||||||||||||

Published works

Articles

- "America Needs a Foreign Legion!" Argosy (Jan. 1966).

Books

- Guerrilla Resistance Movement in the Philippines, 1941–1945. New York: Vantage (1972).

- MacArthur, 1941–1951. New York: McGraw-Hill (1954).

- Shanghai Conspiracy: The Sorge Spy Ring, Moscow, Shanghai, Tokyo, San Francisco, New York. Preface by General Douglas MacArthur. New York: Dutton (1952); Boston: Western Islands (1965).

- Intelligence Series: G-2 USAFFE, SWPA, AFPAC, FEC, SCAP. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office (1948).

- Campaigns of MacArthur in the Pacific

- Japanese Operations Against MacArthur

- MacArthur in Japan: Military Phases (undated

- Written by Willoughby and a team of American and Japanese military commanders after World War II. Intended to be the basis for General MacArthur's memoirs, the final version disappeared after President Truman dismissed MacArthur. No copy has turned up in either MacArthur's or Willoughby's papers.

In popular culture

General Willoughby is frequently mentioned in author W. E. B. Griffin's series "The Corps", usually in an unflattering light. Willoughby appears frequently as one of MacArthur's key advisors in James Webb's historical novel The Emperor's General.

See also

General bibliography

- Papers of Major General Charles A. Willoughby, USA 1947-1973

- Campbell, Kenneth J. "Major General Charles A. Willoughby: A Mixed Performance". Text of unpublished paper.

- Foy, David A. (2023). Loyalty First: The Life and Times of Charles A. Willoughby, MacArthur's Chief Intelligence Officer. Havertown, PA: Casemate Publishers. ISBN 9781636243498.

- Takemae, Eiji (2002). Inside GHQ: The Allied Occupation of Japan and Its Legacy. Translated by Ricketts, Robert; Swann, Sebastian. New York: Continuum. ISBN 0826462472. OL 6796320M – via Internet Archive.

Citations

- ↑ Kluckhohn, Frank (19 August 1952). "Heidelberg to Madrid — The Story of General Willoughby". The Reporter (New York Journal). Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Charles Andrew Willoughby, Major General, United States Army". Arlington National Cemetery. 14 December 2004. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- 1 2 3 Finley, James (1999). "Charles Willoughby: World War II Intelligence in the Pacific Theater" (PDF). Fort Huachuca: US Army Intelligence Center. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2010. Retrieved 3 November 2010.

- ↑ Edward Drea (et al.): Researching Japanese War Crimes Records: Introductory Essays. Washington 2006, ISBN 1-880875-28-4; Chapter 8

- ↑ "SCAPIN-33: PRESS CODE FOR JAPAN 1945/09/19". National Diet Library Digital Collections. Retrieved 2021-03-07.

- ↑ "GHQ/SCAP Records, Assistant Chief of Staff (G-2)". National Diet Library (Japanese). Retrieved 2021-03-07.

- ↑ Kaplan, David E.; Dubro, Alec (2003). Yakuza: Japan's Criminal Underworld. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520274907.

- ↑ Takemae 2002, pp. 161–165.

- 1 2 CIA papers reveal 1950s Japan coup plot

- ↑ "Reports on the rearmament actitivites of TSUJI Masanobu and HATTORI Takushiro" (PDF). CIA Archives. Unclassified in 2005: 2. 28 January 1954.

- ↑ Johnson, Chalmers (November 20, 2003). "The Looting of Asia": A review of Gold Warriors: America's Secret Recovery of Yamashita's Gold by Sterling Seagrave and Peggy Seagrave Verso, 332 pp. London Review of Books v. 25, no. 22. Archived from the original on November 19, 2003. Retrieved January 13, 2021.

- ↑ Seagrave, Sterling; Seagrave, Peggy (January 1, 2003). Gold Warriors: America's Secret Recovery of Yamashita's Gold. Verso. ASIN B00SQDO3GU.

- ↑ Seagrave, Sterling; Seagrave, Peggy (December 26, 2005). Gold Warriors: America's Secret Recovery of Yamashita's Gold. Verso. ISBN 978-1844675319.

- ↑ Haberstam, David; The Coldest Winter; New York 2007, ISBN 978-1-4013-0052-4

- ↑ Gordon, Andrew; A modern history of Japan; Oxford 2009, ISBN 978-0-19-533922-2; S 237

- ↑ "The Only Woman in the Room: Beate Sirota Gordon, 1923-2012". Dissent Magazine. Retrieved 2018-12-07.

- ↑ Frank, Richard. MacArthur; New York 2007, ISBN 978-1-4039-7658-1

- ↑ Halberstam, David (24 September 2007). "MacArthur's Grand Delusion". Vanity Fair. Condé Nast. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ↑ "Reports on the rearmament actitivites of TSUJI Masanobu and HATTORI Takushiro" (PDF). CIA Archives. Unclassified in 2005: 2. 28 January 1954.

- ↑ CIA papers reveal 1950s Japan coup plot

- ↑ "The Strange Love of Dr. Billy James Hargis | This Land Press - Made by You and Me".