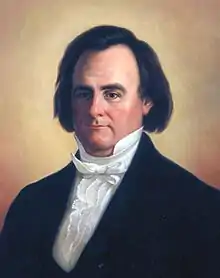

Charles A. Wickliffe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Kentucky's 5th district | |

| In office March 4, 1861 – March 3, 1863 | |

| Preceded by | John Brown |

| Succeeded by | Robert Mallory |

| 11th United States Postmaster General | |

| In office September 13, 1841 – March 4, 1845 | |

| President | John Tyler |

| Preceded by | Francis Granger |

| Succeeded by | Cave Johnson |

| 14th Governor of Kentucky Acting | |

| In office August 27, 1839 – September 2, 1840 | |

| Preceded by | James Clark |

| Succeeded by | Robert P. Letcher |

| 11th Lieutenant Governor of Kentucky | |

| In office August 31, 1836 – August 27, 1839 | |

| Governor | James Clark |

| Preceded by | James Morehead |

| Succeeded by | Manlius Valerius Thomson |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Kentucky's 9th district | |

| In office March 4, 1823 – March 3, 1833 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas Montgomery |

| Succeeded by | James Love |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Charles Anderson Wickliffe June 8, 1788 Springfield, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | October 31, 1869 (aged 81) Ilchester, Maryland, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic-Republican (Before 1825) Whig (1834–1852) Unionist (1852–1863) Democratic (1863–1866) |

| Spouse | Margaret Crepps |

| Children | Robert |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Battles/wars | War of 1812 |

Charles Anderson Wickliffe (June 8, 1788 – October 31, 1869) was a U.S. Representative from Kentucky. He also served as Speaker of the Kentucky House of Representatives, the 14th Governor of Kentucky, and was appointed Postmaster General by President John Tyler. Though he consistently identified with the Whig Party, he was politically independent, and often had differences of opinion with Whig founder and fellow Kentuckian Henry Clay.

Wickliffe received a strong education in public school and through private tutors. He studied law and was part of a debate club that also included future U.S. Attorney General Felix Grundy and future Governor of Florida William Pope Duval. He was elected to the Kentucky House of Representatives in 1812. A vigorous supporter of the War of 1812, he served for a brief time as aide-de-camp to two American generals in the war. In 1823, he was elected to the first of five consecutive terms in the U.S. House of Representatives. He returned to the state House in 1833, and was elected the tenth Lieutenant Governor of Kentucky in 1836. Governor James Clark died in office on October 5, 1839, and Wickliffe served as governor for the remaining nine months of Clark's term.

President Tyler appointed Wickliffe as Postmaster General following Wickliffe's term as governor. While aboard a steamship in 1844, he was stabbed by a man who was later found to be insane. In 1845, President James K. Polk sent Wickliffe on a secret mission to report on British and French intents with regard to annexing Texas and to assess the feasibility of the United States undertaking such an action. Wickliffe's participation in this endeavor further distanced him from the Whigs.

In 1861, Wickliffe was again elected to the U.S. House, serving a single term. He tried to avert the Civil War by serving as a delegate to both the 1861 Peace Conference and the Border States Convention. After war was declared, he sided with the Union cause. In 1863, he again sought the office of governor, but federal military forces interfered with the election, resulting in a landslide victory for Thomas E. Bramlette. Later in life, Wickliffe was crippled in a carriage accident and also went completely blind. He died on October 31, 1869, while visiting his daughter in Maryland.

Early life

Charles Anderson Wickliffe was born June 8, 1788, in a log cabin near Springfield, Kentucky.[1] He was the youngest of the nine children born to Charles and Lydia (Hardin) Wickliffe.[2] His family emigrated to Kentucky from Virginia in 1784.[3]

Wickliffe attained his early education at the local schools of Springfield, then attended Wilson's Academy in Bardstown.[2] For a year, he received private instruction from James Blythe, acting president of Transylvania University, then read law with Martin D. Hardin, a cousin on his mother's side.[2][4][5] In 1809, he was admitted to the bar and began practice in Bardstown.[6] He owned slaves.[7] He and five other prominent lawyers of Bardstown formed a debate club called The Pleiades Club.[8] The club included six members: Wickliffe, John Hays, Ben Chapeze, Benjamin Hardin (another of Wickliffe's cousins), Felix Grundy, and William Pope Duval.[8] John Rowan and John Pope also participated in the debates, but were not members of the club.[2]

In his early life, Wickliffe was known to gamble at cards. His friends considered his gambling excessive, and two of them – Duval and Judge John Pope Oldham – devised a scheme to break Wickliffe of his habit. The two knew that Wickliffe would be collecting several thousand dollars at the upcoming session of the Bullitt County court. They plotted to invite Wickliffe to play cards with them and agreed upon a secret system of signals to communicate about the strengths and weaknesses of the cards in their hands. In this way, they hoped to win all of Wickliffe's money, then return it to him in exchange for his promise to forsake the vice. On the night appointed, however, it was Wickliffe who won all the money wagered by Duval and Oldham, despite their schemes. When Wickliffe later learned of the designs of his friends, he agreed to give up gambling.[9]

In 1813, Wickliffe married Margaret Cripps, and the couple had three sons and five daughters.[2][4] Most notable among the children was Robert, who became Governor of Louisiana.[2] His daughter Nancy married David Levy Yulee.

The Wickliffes contracted with John Rogers, architect of St. Joseph's Cathedral in Bardstown, to construct their residence, which they dubbed "Wickland".[10] Later, Wickland was called "the home of three governors".[10] Besides Wickliffe and his son, J. C. W. Beckham, Wickliffe's grandson and future governor of Kentucky, occupied the residence.[10]

Political career

Wickliffe's political career began when he was elected to represent Nelson County in the Kentucky House of Representatives in 1812 and 1813.[2] During his tenure, he enthusiastically supported the War of 1812.[2] He first served as an aide-de-camp to General Joseph Winlock, and on August 24, 1813, he enlisted as a private in Martin H. Wickliffe's company.[11] On September 2, 1813, he was chosen as aide-de-camp to General Samuel Caldwell and served in this capacity at the October 5, 1813, Battle of the Thames.[6][11] In 1816, he succeeded Ben Hardin as Commonwealth's Attorney for Nelson County.[2]

Wickliffe was returned to the Kentucky House in 1822 and 1823.[6] During this period, a controversy known as the Old Court-New Court controversy was raging in Kentucky. Reeling from the financial Panic of 1819, many of the state's citizens demanded debt relief. When some debt relief measures passed by the legislature were declared unconstitutional by the Kentucky Court of Appeals, the legislature attempted to dissolve the court and replace it with a more sympathetic one. For a time, two courts claimed to be the court of last resort in Kentucky. Wickliffe supported the "Old Court", which was the court that eventually prevailed.[12]

First service in the House of Representatives

In 1823, Wickliffe was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives and served five consecutive terms.[6] Again he succeeded his cousin and friend, Ben Hardin.[13] Though a Whig, he disagreed with many of the positions of the party's founder, Henry Clay.[1] When no candidate received a majority of the electoral votes in the 1824 presidential election, the constitution mandated that the election be decided in the House.[10] Wickliffe bucked Clay's advice to vote for him and instead voted for Andrew Jackson, who was the choice of the Kentucky legislature.[10]

Historian Robert Powell opined that Wickliffe's break from party loyalty may explain his lack of committee appointments in his early years in the House.[2] Beginning in 1829, however, he chaired the Committee on Public Lands.[2] In this capacity, he attacked Clay's plan to distribute surplus revenue among the states as being unfair to younger states.[10] He also differed with Clay over Clay's willingness to limit slavery.[10] He wrote Clay concerning his slowness to respond to the problem of fugitive slaves; Clay never responded.[10] Neither was Wickliffe loyal to the Jacksonian platform, however. In a letter to his brother, he lamented Jackson's attacks on the Second Bank of the United States.[10] He publicly encouraged Kentuckians to strengthen the Whigs, despite his disagreements with Clay.[10]

In 1830, Wickliffe was chosen by his colleagues as one of the managers of the impeachment trial proceedings against Missouri District Court judge James H. Peck.[6] In 1831, he was one of several candidates proposed by the Kentucky General Assembly to succeed John Rowan in the U.S. Senate.[14] Of the sixty-nine votes needed to be elected to the seat, Wickliffe received forty-nine.[14] Other candidates included John J. Crittenden (sixty-eight votes), John Breathitt (sixty-six votes), and Richard Mentor Johnson (sixty-four votes).[14] After three days of balloting, the Assembly was still unable to fill the seat, and it was allowed to remain vacant until the next session.[14] Wickliffe did not seek re-election to his seat in the House in 1833.[6]

Governor of Kentucky

Wickliffe returned to the state legislature from 1833 to 1835.[6] In 1834, he defeated Daniel Breck and John L. Helm to become Speaker of the House.[15] He was elected lieutenant governor of Kentucky in 1836, defeating Democrat Elijah Hise by a margin of just over 1,300 votes.[15] Upon the death of Governor James Clark on October 5, 1839, he became acting governor and served the remaining nine months of Clark's term.[6]

As governor, Wickliffe's primary concern was the Panic of 1837.[1] He advocated raising property taxes to offset spending deficits that had climbed to $42,000 by 1839, but the legislature borrowed money to meet the current expenses instead.[1] Wickliffe maintained the state's credit by paying the interest due on state securities.[1] The only areas where he called for more spending were improvements in river navigation, preservation of state archives, and public education.[1] Aside from these concerns, he was inundated with requests for clemency.[1]

Service to Presidents Tyler and Polk

Wickliffe campaigned on behalf of the Whig ticket of William Henry Harrison and John Tyler in the presidential election of 1840.[16] Wickliffe and Tyler were friends, having shared a room when they were both in Congress.[16] When Harrison's death elevated Tyler to the office of president, Tyler appointed Wicklilffe as Postmaster General, a choice that angered Clay supporters in the party.[16] Wickliffe served in Tyler's administration until March 1845.[6]

On August 1, 1844, Wickliffe and two of his daughters boarded the steamship Georgia traveling from Old Point Comfort in Virginia to Baltimore, Maryland.[17] While en route, he was stabbed in the chest by a man wielding a claspknife.[8] The knife bounced off Wickliffe's breastbone without damaging any major internal organs, and a U.S. Navy officer prevented a second blow from hitting Wickliffe.[17] Wickliffe's attacker, J. McLean Gardner, was disarmed and arrested.[17] Later that night, he wrote Wickliffe a letter of apology.[17] Wickliffe was not seriously injured, and returned home three days after the attack.[17] Gardner was tried and found to be insane; he was later sent to an asylum.[8]

Wickliffe supported the annexation of Texas, an issue that helped seal Clay's defeat in the 1844 presidential canvass.[18] In 1845, President James K. Polk sent Wickliffe as an envoy on a secret mission to the Republic of Texas.[19] Originally, his purpose was to quash British and French attempts to forestall the U.S. annexation of Texas, but he later joined Commodore Robert F. Stockton in lobbying leaders of the Republic of Texas to order their military forces across the Rio Grande into Mexico.[20] Stockton and Wickliffe believed that if they could provoke a Texan invasion of Mexico, the United States would have a stronger case for annexing Texas.[20] Ultimately, they failed in convincing the Texans to invade, but succeeded in drumming up support for annexation.[20] Both Wickliffe's position on annexation and his willingness to carry out Polk's assignment further distanced him from the Whigs.[1]

Later political career

On February 18, 1841, the Kentucky General Assembly elected James Turner Morehead to the U.S. Senate; Wickliffe received twenty votes in this contest.[21] In 1849, he was chosen as a delegate to the state constitutional convention, despite having opposed the calling of such a convention a decade earlier.[6][21] Wickliffe's political opponents, including Thomas F. Marshall, claimed this showed Wickliffe's political inconsistency, a charge that Wickliffe denied.[21] The following year, Wickliffe was appointed to a committee charged with revising the state's code of laws.[2] On January 8, 1861, he chaired the state Democratic convention in Louisville.[22]

Wickliffe was elected to another term in Congress, serving from 1861 to 1863 as a Union Whig.[6] He opposed the idea of secession, and was a member of both the 1861 Peace Conference and the Border States Convention that attempted to stave off the Civil War.[2] In April 1861, he attended a secret meeting at the Capitol Hotel in Frankfort where participants planned to arm Union supporters in key areas of the state.[23] On May 18, President Lincoln supplied rifles – nicknamed "Lincoln guns" – for the venture.[24] After Braxton Bragg's forces destroyed the railroad trestles near Bardstown, Wickliffe personally hired Joseph Z. Aud to carry the area's mail by private carriage.[25] The trestles were rebuilt in February 1863, precluding the need for Aud's service.[25]

Near the end of his term in Congress, Wickliffe was thrown from a carriage and permanently crippled.[2] Despite his injury, he remained politically active. In 1863, he ran for governor as a Peace Democrat on an anti-Lincoln platform.[4] Military authorities considered him subversive, however, and interfered with the election; Wickliffe lost to Thomas E. Bramlette in a landslide.[1][22]

Wickliffe served as a delegate to the 1864 Democratic National Convention in Chicago, casting his vote for George B. McClellan.[22] In the final years of his life, he became totally blind.[3] While visiting his daughter near Ilchester, Maryland, he fell gravely ill and died on October 31, 1869.[18] He was buried in Bardstown Cemetery in Bardstown.[6] During World War I, a U.S. naval ship was named in Wickliffe's honor.[26]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Harrison, p. 950

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Powell, p. 38

- 1 2 Allen, p. 104

- 1 2 3 Encyclopedia of Kentucky, p. 78

- ↑ Little, p. 203

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Biological Directory of the United States Congress

- ↑ "Congress slaveowners", The Washington Post, January 13, 2022, retrieved July 6, 2022

- 1 2 3 4 Hibbs, p. 40

- ↑ Little, pp. 33–34

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Heck, p. 52

- 1 2 Trowbridge, "Kentucky's Military Governors"

- ↑ Little, p. 107

- ↑ Little, p. 98

- 1 2 3 4 Little, p. 156

- 1 2 Little, p. 204

- 1 2 3 Heck, p. 53

- 1 2 3 4 5 Niles' National Register, p. 353

- 1 2 Heck, p. 54

- ↑ National Governors Association

- 1 2 3 Bullock

- 1 2 3 Little, p. 205

- 1 2 3 Little, p. 210

- ↑ Hibbs, p. 68

- ↑ Hibbs, p. 69

- 1 2 Hibbs, p. 80

- ↑ Hibbs, p. 140

Bibliography

- Allen, William B. (1872). A History of Kentucky: Embracing Gleanings, Reminiscences, Antiquities, Natural Curiosities, Statistics, and Biographical Sketches of Pioneers, Soldiers, Jurists, Lawyers, Statesmen, Divines, Mechanics, Farmers, Merchants, and Other Leading Men, of All Occupations and Pursuits. Bradley & Gilbert. Retrieved November 10, 2008.

- Bullock, Jason (1998). The United States and Mexico at War. Macmillan Reference USA.

- United States Congress. "Charles A. Wickliffe (id: W000442)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Encyclopedia of Kentucky. New York, New York: Somerset Publishers. 1987. ISBN 0-403-09981-1.

- "Kentucky Governor Charles Anderson Wickliffe". National Governors Association. Archived from the original on October 20, 2009. Retrieved December 16, 2008.

- Harrison, Lowell H. (1992). Kleber, John E. (ed.). The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1772-0.

- Heck, Frank H. (2004). Lowell H. Harrison (ed.). Kentucky's Governors. The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2326-7.

- Hibbs, Dixie (2002). Bardstown: Hospitality, History and Bourbon. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-2391-7. Retrieved February 1, 2009.

- Little, Lucius P. (1887). Ben Hardin: His Times and Contemporaries, with Selections from His Speeches. Courier-journal job printing company. Retrieved February 1, 2009.

- "The Postmaster General". Niles' National Register. Ayer Publishing. 64 (23). August 5, 1844. ISBN 0-8337-2546-7. Retrieved May 25, 2009.

- Powell, Robert A. (1976). Kentucky Governors. Danville, Kentucky: Bluegrass Printing Company. ASIN B0006CPOVM. OCLC 2690774.

- Trowbridge, John M. "Kentucky's Military Governors". Kentucky National Guard History e-Museum. Kentucky National Guard. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved April 23, 2010.

Further reading

- Guelzo, Allen C. (2006). Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation: The End of Slavery in America. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-9965-5. Retrieved February 1, 2009.

- Morton, Jennie C. (September 1904). "Governor Charles A. Wickliffe". The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. 2 (6): 17–21.

- Speed, Thomas (1907). The Union Cause in Kentucky, 1860–1865. G.P. Putnam's Sons. ISBN 9780722283387. Retrieved February 1, 2009.

External links

- Cemetery Memorial by La-Cemeteries