| Cathedral of Saint Stephen, Paris | |

|---|---|

| Basilica and Cathedral of Saint Stephen, Paris | |

| Cathédrale Saint-Étienne de Paris | |

Basilique-Cathédrale Saint-Étienne de Paris | |

Location of the Cathedrale Saint-Étienne de Paris, in front of Notre-Dame de Paris | |

| 48°51′12.24″N 2°20′55.68″E / 48.8534000°N 2.3488000°E | |

| Location | |

| Country | |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| History | |

| Status | Demolished and replaced by Notre-Dame de Paris |

| Dedication | Saint Stephen |

| Architecture | |

| Functional status | Basilica Cathedral |

| Style | Merovingian, Carolingian, Romanesque |

| Groundbreaking | 4th or 5th century |

| Demolished | 12th century |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 70 m (229 ft 8 in) |

| Width | 35 m (114 ft 10 in) |

| Administration | |

| Diocese | Paris |

The Basilica and Cathedral of Saint-Étienne in Paris, on the Île de la Cité, was an early Christian church that preceded Notre-Dame de Paris. It was built in the 4th or 5th century, directly in front of the location of the modern cathedral, and just 250 meters from the royal palace. It became one of the wealthiest and most prestigious churches in France. Nothing remains above the ground of the original cathedral. It was demolished beginning in about 1163, when construction began on Notre-Dame de Paris. Vestiges of the foundations remain beneath the pavement of the square in front of Notre-Dame and beneath the west front of the cathedral.[1][2] The church was built and rebuilt over the years in the Merovingian, Carolingian and Romanesque architectural styles.[3]: 320–321

History

Historians differ on the date when the Cathedral was begun. According to Alain Erlande-Brandenburg, a basilica existed there in 4th century, while Michel Fleury wrote that the cathedral was built later, during the reign of Childebert I (511–558), the son and successor of Clovis, the first French king to convert to Christianity.[4]

The first mention with certainty of a cathedral on the Île de la Cité was made in the 6th century, though it is very probable that a cathedral was there in the 5th century. The Life of Saint Genevieve recounts that, in 451, when the Huns attacked Paris, Saint Genevieve summoned the Christians to pray inside the baptistry which adjoined the cathedral.[5]

It appears from the excavation that the cathedral was originally built upon an earlier Roman foundation, and when it was rebuilt in the 6th century stone from the earlier basilica was used.

Excavations

The foundations of an early structure were first discovered in 1711 at a depth of about six feet under the modern cathedral floor during the digging of a sepulchre for the Bishops of the Cathedral. The workers discovered two ancient walls on the south side, one about five feet thick, the other two and a half feet thick. The two walls were designed to support each other. They also discovered an extraordinary collection of nine Gallo-Roman statues, including the pieces of the Pillar of the Boatmen, a Roman monument erected by Paris boatmen in the first century.[3]

In 1858 much more extensive excavations were carried out under Notre-Dame and surroundings, with the participation of Eugène Viollet-le-Duc. In the same area as the crypt of the archbishops, at the second traverse of the choir, about twelve meters east of the transept, half a meter below the floor of the choir, they discovered the foundations of the early apse. Digging deeper, they found the vestiges of two different churches at different depths, including the elements of a rectangular chevet, or east end, of an earlier church.[3]

More recent extensive excavations were carried out by Michel Fleury between 1965 and 1972. They uncovered elements of architecture and decoration, including fragments of marble decoration, capitals, columns, colonettes, and pavement. These are now on display in the Musée de Cluny, the National Museum of the Middle Ages.

Description

San Vitale, a 5th-century basilica in Rome

San Vitale, a 5th-century basilica in Rome Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy (6th c.)

Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy (6th c.) Merovingian basilica in Metz (6th c.)

Merovingian basilica in Metz (6th c.)

The outside appearance of St. Étienne is unknown, but it probably resembled similar pre-Romanesque basilicas of the period such as San Vitale, Rome, the Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna and the Basilica of Saint-Pierre-aux-Nonnains in Metz. It appears that there may have been a bell tower in the center of the west front, based on the massive foundation there. It may also have had a central dome or lantern. The interior was decorated with mosaics and sculpture. Fragments of marble, furniture and pottery were found in the excavations.[6]

Based on the foundation, it appears the church was seventy meters long, including the porch, or half the length of Notre-Dame de Paris, and thirty-five meters wide. Marble pillars in the nave supported the roof of the nave, which was about ten meters wide. It appears that it had four lower collateral aisles, on either side of the nave; one 5 meters wide and one 3.5 meters wide. The second collateral aisle on the south side was built atop a rampart from the late Roman Empire.[6]

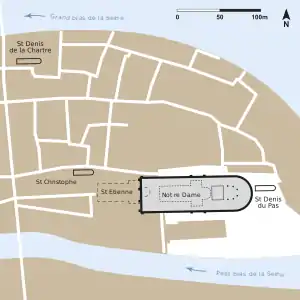

The cathedral was the largest of a group of episcopal buildings on the site. At the end of the High Middle Ages, in addition to Saint Étienne, there was a church devoted to the Virgin Mary, a separate baptistry (at a time when adults, rather than children, were baptised), and a chapel dedicated to Saint Christopher, just west of Notre-Dame. Its foundations were discovered in 1845. The foundations of another small church, dedicated to Saint Denis, were found just to the east of the chevet of Notre-Dame. The cathedral also was close to the original Hôtel-Dieu, the first hospital in Paris, built in the 9th century, and later moved to its present location further north.[7]

Vestiges

Vestiges of the foundations of the cathedral are found underneath the parvis, the paved square in front of Notre-Dame de Paris.

Map of other buildings on site

Map of other buildings on site The parvis of Notre-Dame, above the site of Saint-Étienne

The parvis of Notre-Dame, above the site of Saint-Étienne Location of the original porch of Saint-Étienne, in front of Notre-Dame

Location of the original porch of Saint-Étienne, in front of Notre-Dame Plaque on the parvis of Notre-Dame showing the location of the porch of St.-Étienne

Plaque on the parvis of Notre-Dame showing the location of the porch of St.-Étienne

See also

Notes and citations

- ↑ Lenoir, Albert; Berty, Adolphe. "Histoire topographique et archéologique de l'ancien Paris : Plan de restitution", Paris, Martin et Fontet".

- ↑ Lours, Dictionnaire des Cathédrales (2018), p. 290

- 1 2 3 Salet, François, "La Cathédrale mérovingienne Saint-Étienne de Paris", "Bulletin Monumental" (1970)

- ↑ Fierro (1995), p. 339

- ↑ Fierro, "Histoire and Dictionnaire de Paris" (1996), pg. 339

- 1 2 Erlander-Brandenburg, "L'Ensemble Cathédrale de Paris du IV siècle", "Persee".

- ↑ Jean Hubert, "Les Origins de Notre-Dame de Paris", "Revue d'histoire de l'Église de France" (1964), pp. 5–26

Bibliography (in French)

- Fierro, Alfred (1996). Histoire et dictionnaire de Paris. Robert Laffont. ISBN 2-221--07862-4.

External links (in French)

- Alain Erlande-Brandenburg, « L'ensemble cathédral de Paris, du IVe siècle », in the Bulletin de la Société nationale des Antiquaires de France - 1995, 1997, p. 186-189 (read on-line)

- Michel Fleury, « La cathédrale mérovingienne de Paris. Plan et datation », in Landschaft und Geschichte, Festschrift für Franz Petri für seinem 65. Geburtstag, Bonn, 1970, pp. 211-221, 2fig. (compte-rendu par Francis Salet, dans Bulletin Monumental, 1970, tome 128, no 4, p. 320-321)

- Michel Fleury, « La Cathédrale Saint-Étienne de Paris » dans Dossiers d'Archéologia no 218, November 1996, p. 40-45.

- Jean Hubert, « Les origines de Notre-Dame de Paris », in : Revue d'histoire de l'Église de France, t. L, 1964, pp. 5-26, 3 fig. (read on-line)

- Jean Hubert, « Les cathédrales doubles et l'histoire de la liturgie », in Atti del primo Convegno internazionale studi longobardi, Spoleto, 27-30 September 1951, Spolète, 1952 Accademia spoletina, pp.167-176, 3 fig., and "Les cathédrales doubles de la Gaule", in Mélanges d'histoire et d'archéologie offerts en hommage à M. Louis Blondel, Genava,new series t. XI, 1963, p. 105-125, 8 fig.

(For additional links to the French-language articles, see "Cathédrale Saint-Étienne de Paris" in the French Wikipedia)