.jpg.webp)

A cartouche (also cartouch) is an oval or oblong design with a slightly convex surface, typically edged with ornamental scrollwork. It is used to hold a painted or low-relief design.[1] Since the early 16th century, the cartouche is a scrolling frame device, derived originally from Italian cartuccia. Such cartouches are characteristically stretched, pierced and scrolling.

Another cartouche figures prominently in the 16th-century title page of Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, framing a minor vignette with a pierced and scrolling papery cartouche.

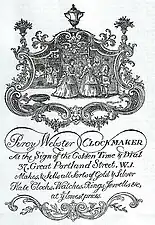

The engraved trade card of the London clockmaker Percy Webster shows a vignette of the shop in a scrolling cartouche frame of Rococo design that is composed entirely of scrolling devices.

History

Antiquity

Cartouches are found on buildings, funerary steles and sarcophagi. The cartouche is generally rectangular, delimited by a molding or one or more incised lines, with two symmetrical trapezoids on the lateral edges.

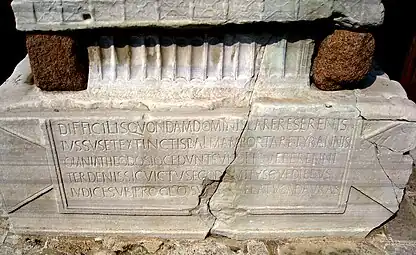

Roman rectangular cartouche on a sarcophagus, 3rd century, marble, Adana Archaeology Museum, Adana, Turkey

Roman rectangular cartouche on a sarcophagus, 3rd century, marble, Adana Archaeology Museum, Adana, Turkey Roman cartouche on the pedestal of the Obelisk of Theodosius, Hippodrome of Constantinople, Istanbul, Turkey, unknown architect or sculptor, 390[3]

Roman cartouche on the pedestal of the Obelisk of Theodosius, Hippodrome of Constantinople, Istanbul, Turkey, unknown architect or sculptor, 390[3] Roman cartouche on the right leaf of the Symmachi–Nicomachi diptych, c.400, ivory, Victoria and Albert Museum, London[4]

Roman cartouche on the right leaf of the Symmachi–Nicomachi diptych, c.400, ivory, Victoria and Albert Museum, London[4]

Chinese

Chinese cartouches, illustration from L'Ornement Polychrome, by Albert Racinet, 1888

Chinese cartouches, illustration from L'Ornement Polychrome, by Albert Racinet, 1888

From the Renaissance to Art Deco

The Renaissance brought back elements of Greco-Roman culture, including ornaments like the cartouche. Compared to their ancient ancestors, the ones from the Renaissance are usually much more complex. Cartouches continue to be used in styles that succeed the Renaissance. Most have the usual look of a symmetrical oval with scrolls developed during the Renaissance and Baroque periods, but some are highly stylized, showing the diversity of styles popular over time. They were used constantly, and were one of the main motifs of Rococo and Beaux Arts architecture.

Their use started to fade in Art Deco, a style created as a collective effort of multiple French designers to make a new modern style around 1910. This is because of the fact that artists of this movement tried to create new ornaments for their time, most often stylizing motifs used before, or coming up with completely new ones. Art Deco also followed the principle of simplicity, another reason for the rarity of complex ornaments like cartouches or mascarons in Art Deco.

Renaissance stucco cartouche on a wall in the Gallery of Francis I, Palace of Fontainebleau, Fontainebleau, France, by Rosso Fiorentino, designed in 1532[6]

Renaissance stucco cartouche on a wall in the Gallery of Francis I, Palace of Fontainebleau, Fontainebleau, France, by Rosso Fiorentino, designed in 1532[6] Renaissance cartouches on the Monument for the heart of Francis I, Basilica of Saint-Denis, Saint-Denis, France, by Pierre Bontemps, 1556[7]

Renaissance cartouches on the Monument for the heart of Francis I, Basilica of Saint-Denis, Saint-Denis, France, by Pierre Bontemps, 1556[7]

%252C_RP-P-1890-A-15504.jpg.webp) Two Renaissance cartouches, a big one with Alexander the Great and a smaller one with an inscription, by Crispijn van de Passe the Elder, 1574-1637, engraving on paper, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, the Netherlands

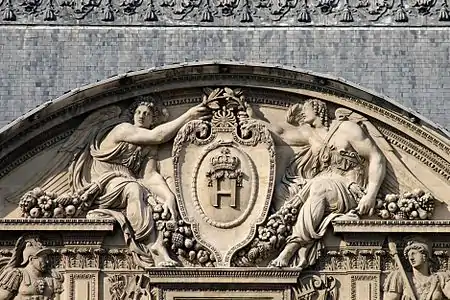

Two Renaissance cartouches, a big one with Alexander the Great and a smaller one with an inscription, by Crispijn van de Passe the Elder, 1574-1637, engraving on paper, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, the Netherlands Renaissance cartouche in a pediment of the west facade of the Cour Carrée of the Louvre Palace, Paris, designed by Pierre Lescot, 16th century[9]

Renaissance cartouche in a pediment of the west facade of the Cour Carrée of the Louvre Palace, Paris, designed by Pierre Lescot, 16th century[9] 16th and 17th century Renaissance cartouches from L'Ornement Polychrome, by Albert Racinet, 1888

16th and 17th century Renaissance cartouches from L'Ornement Polychrome, by Albert Racinet, 1888 Baroque cartouche at the entrance of St. Peter's Basilica, Rome, unknown architect or blacksmith, c.1615

Baroque cartouche at the entrance of St. Peter's Basilica, Rome, unknown architect or blacksmith, c.1615 Design of a Baroque cartouche, by Stefano della Bella, 1647, etching on paper, Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, US

Design of a Baroque cartouche, by Stefano della Bella, 1647, etching on paper, Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, US_(40185455721).jpg.webp) Baroque cartouche with putti, above a mirror in the bedchamber of the Mecklenburg Apartment, Charlottenburg Palace, Berlin, unknown architect, 17th century

Baroque cartouche with putti, above a mirror in the bedchamber of the Mecklenburg Apartment, Charlottenburg Palace, Berlin, unknown architect, 17th century Brâncovenesc cartouche on a damaged stone in the courtyard of Antim Monastery, Bucharest, Romania, unknown sculptor, late 17th-early 18th century

Brâncovenesc cartouche on a damaged stone in the courtyard of Antim Monastery, Bucharest, Romania, unknown sculptor, late 17th-early 18th century_MET_DP834139.jpg.webp) Baroque cartouche of the frontispiece for Figures françoises et comiques by Robert Hecquet, possibly 1702, etching in paper, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Baroque cartouche of the frontispiece for Figures françoises et comiques by Robert Hecquet, possibly 1702, etching in paper, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City_(CH_18264721).jpg.webp) Baroque cartouche, unknown date, etching on paper, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York

Baroque cartouche, unknown date, etching on paper, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York Baroque cartouche-shaped corbels on the facade of the Hôtel d'Eynaud (Rue de l'Arbre-Sec no, 52), Paris, unknown architect, 1721

Baroque cartouche-shaped corbels on the facade of the Hôtel d'Eynaud (Rue de l'Arbre-Sec no, 52), Paris, unknown architect, 1721 Baroque cartouche on the edges and corners of The Astronomers, designed by Guy-Louis Vernansal, 1722-1724, wool, silk and tapestry weaving, Louvre

Baroque cartouche on the edges and corners of The Astronomers, designed by Guy-Louis Vernansal, 1722-1724, wool, silk and tapestry weaving, Louvre 18th century Rococo cartouches from L'Ornement Polychrome, by Albert Racinet, 1888

18th century Rococo cartouches from L'Ornement Polychrome, by Albert Racinet, 1888 Rococo cartouche of the Hôtel de Conti (Place du Château no. 14), Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France, unknown architect, 18th century

Rococo cartouche of the Hôtel de Conti (Place du Château no. 14), Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France, unknown architect, 18th century%252C_RP-P-2011-164-8.jpg.webp) Rococo cartouche from the Second Livre de Cartouches, c.1710-1772, Rijksmuseum

Rococo cartouche from the Second Livre de Cartouches, c.1710-1772, Rijksmuseum Baroque cartouche on the Fontana del Pantheon, Rome, by Filippo Barigioni, 1711

Baroque cartouche on the Fontana del Pantheon, Rome, by Filippo Barigioni, 1711 Baroque cartouche of the El Transparente altarpiece, Toledo Cathedral, Toledo, Spain, designed and made by Narciso Tomé, 1729-1732[10]

Baroque cartouche of the El Transparente altarpiece, Toledo Cathedral, Toledo, Spain, designed and made by Narciso Tomé, 1729-1732[10].jpg.webp) Rococo cartouche in the corner of a Versailles plan, by Jean Delagrive, 1746, engraving on paper, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris[11]

Rococo cartouche in the corner of a Versailles plan, by Jean Delagrive, 1746, engraving on paper, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris[11]

Rococo cartouche on a tureen, by the Sèvres porcelain factory, 1757–1758, soft-paste porcelain, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Rococo cartouche on a tureen, by the Sèvres porcelain factory, 1757–1758, soft-paste porcelain, Metropolitan Museum of Art Rococo engraved tradecard of Percy Webster, clockmaker from London, c.1760, engraving, unknown location

Rococo engraved tradecard of Percy Webster, clockmaker from London, c.1760, engraving, unknown location.jpg.webp) Rococo Revival cartouche on a fan, unknown designer and producer, c.1850, paper, gouache, gilding, mother-of-pearl, Musée Galliera, Paris

Rococo Revival cartouche on a fan, unknown designer and producer, c.1850, paper, gouache, gilding, mother-of-pearl, Musée Galliera, Paris Rococo Revival cartouche ob a cone-shaped vase, part of a pair, by Nicolas Bugeard?, mid-19th century, hard-paste porcelain, painted and gilded, Museum of Decorative Arts, Paris

Rococo Revival cartouche ob a cone-shaped vase, part of a pair, by Nicolas Bugeard?, mid-19th century, hard-paste porcelain, painted and gilded, Museum of Decorative Arts, Paris%252C_1855_(CH_18633373).jpg.webp) Renaissance Revival cartouches on a pitcher decorated with coats of arms, unknown artist or producer, 1855, porcelain, overglaze enameling and gilding, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York City

Renaissance Revival cartouches on a pitcher decorated with coats of arms, unknown artist or producer, 1855, porcelain, overglaze enameling and gilding, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York City.jpg.webp) Renaissance Revival cartouches on a display case, designed by Eugène Prignot and Albert-Ernest Carrier de Belleuse, and sculpted by Bernard, 1867, wood and ivory, Petit Palais, Paris

Renaissance Revival cartouches on a display case, designed by Eugène Prignot and Albert-Ernest Carrier de Belleuse, and sculpted by Bernard, 1867, wood and ivory, Petit Palais, Paris Beaux Arts cartouche with a caduceus, on the roof of the Crédit Lyonnais headquarters (Boulevard des Italiens no. 17-23), Paris, by William Bouwens van der Boijen, 1876-1883

Beaux Arts cartouche with a caduceus, on the roof of the Crédit Lyonnais headquarters (Boulevard des Italiens no. 17-23), Paris, by William Bouwens van der Boijen, 1876-1883 Beaux Arts cartouche with a mascaron, above the entrance door of the Académie d'Agriculture de France, Paris, unknown architect, 1878[13]

Beaux Arts cartouche with a mascaron, above the entrance door of the Académie d'Agriculture de France, Paris, unknown architect, 1878[13].jpg.webp) Renaissance Revival cartouche of Rue des Archives no. 9, Paris, unknown architect, c.1880

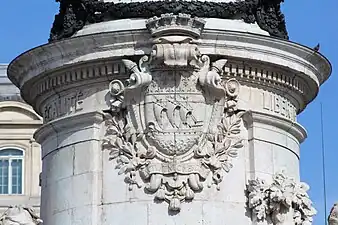

Renaissance Revival cartouche of Rue des Archives no. 9, Paris, unknown architect, c.1880 Beaux Arts mascaron on the Monument à la République by Place de la République, Paris, sculpted by Léopold Morice and designed by François-Charles Morice, 1883

Beaux Arts mascaron on the Monument à la République by Place de la République, Paris, sculpted by Léopold Morice and designed by François-Charles Morice, 1883_-_D%C3%A9tail_de_la_st%C3%A8le_-_Palette.jpg.webp) Beaux Arts cartouche as a painter's palette of the Grave of Gustave Jundt, Montparnasse Cemetery, Paris, by Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, c.1884

Beaux Arts cartouche as a painter's palette of the Grave of Gustave Jundt, Montparnasse Cemetery, Paris, by Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, c.1884 Renaissance Revival polychrome cartouche on the facade of the Toulon Art Museum, designed by Gaudensi Allar and sculpted by Victorien Bastet, c.1888

Renaissance Revival polychrome cartouche on the facade of the Toulon Art Museum, designed by Gaudensi Allar and sculpted by Victorien Bastet, c.1888.jpg.webp) Neoclassical cartouche on a Pompeian style wall in Strada Nicolae Filipescu no. 45, Bucharest, Romania, unknown architect or painter, c.1890

Neoclassical cartouche on a Pompeian style wall in Strada Nicolae Filipescu no. 45, Bucharest, Romania, unknown architect or painter, c.1890.jpg.webp) Neoclassical cartouches in and under a pediment of the Traian Hall (Calea Călărașilor no. 133), Bucharest, by Giulio Magno, 1896

Neoclassical cartouches in and under a pediment of the Traian Hall (Calea Călărașilor no. 133), Bucharest, by Giulio Magno, 1896 Beaux-Arts cartouche of the Pont Alexandre III, Paris, designed by Joseph Cassien-Bernard and Gaston Cousin, 1896-1900

Beaux-Arts cartouche of the Pont Alexandre III, Paris, designed by Joseph Cassien-Bernard and Gaston Cousin, 1896-1900.jpg.webp) Art Nouveau cartouche on the Alexandru Gr. Ionescu House (Bulevardul Lascăr Catargiu no. 4), Bucharest, by Eduard Romantxo, 1898[14]

Art Nouveau cartouche on the Alexandru Gr. Ionescu House (Bulevardul Lascăr Catargiu no. 4), Bucharest, by Eduard Romantxo, 1898[14] Rococo Revival stucco with cartouches in the corners on a ceiling of the Cantacuzino Palace, Bucharest, by Ion D. Berindey, 1898-1906[15]

Rococo Revival stucco with cartouches in the corners on a ceiling of the Cantacuzino Palace, Bucharest, by Ion D. Berindey, 1898-1906[15].jpg.webp) Complex Beaux Arts cartouche of Intrarea Costache Negri no. 1, Bucharest, unknown architect, 1899

Complex Beaux Arts cartouche of Intrarea Costache Negri no. 1, Bucharest, unknown architect, 1899 Beaux Arts cartouche above the entrance of the Hôtel Le Vavasseur (Rue Boissière no. 21), Paris, by Ernest Sanson, 1899

Beaux Arts cartouche above the entrance of the Hôtel Le Vavasseur (Rue Boissière no. 21), Paris, by Ernest Sanson, 1899 Beaux Arts cartouche on facade of the Cozette Boulangerie (Rue Montgallet no. 19), Paris, unknown architect or painter, late 19th century[16]

Beaux Arts cartouche on facade of the Cozette Boulangerie (Rue Montgallet no. 19), Paris, unknown architect or painter, late 19th century[16].jpg.webp) Stylized Beaux Arts cartouche of the Monumental Portico Jules-Félix Coutan in the Square Félix-Desruelles, Paris, by Jules Coutan or Charles-Auguste Risler, before 1900

Stylized Beaux Arts cartouche of the Monumental Portico Jules-Félix Coutan in the Square Félix-Desruelles, Paris, by Jules Coutan or Charles-Auguste Risler, before 1900 Beaux Arts cartouche of the Pont de Bir-Hakeim, Paris, by Jean Camille Formigé, Louis Biette and Daydé & Pillé, 1903-1905

Beaux Arts cartouche of the Pont de Bir-Hakeim, Paris, by Jean Camille Formigé, Louis Biette and Daydé & Pillé, 1903-1905.jpg.webp) Gothic Revival shield-like cartouches on the Hermann I.Rieber carriage factory (Strada Romulus no. 17), Bucharest, by Siegfrid Kofczinsky, 1903[17]

Gothic Revival shield-like cartouches on the Hermann I.Rieber carriage factory (Strada Romulus no. 17), Bucharest, by Siegfrid Kofczinsky, 1903[17]_1.jpg.webp) Romanian Revival cartouche above a window of the Aurel Mincu House (Bulevardul Dacia no. 60), Bucharest, by Arghir Culina, 1910[18]

Romanian Revival cartouche above a window of the Aurel Mincu House (Bulevardul Dacia no. 60), Bucharest, by Arghir Culina, 1910[18] Highly stylized Art Nouveau cartouche on Rue Jean-de-La-Fontaine no. 21, Paris, by Hector Guimard, c.1911

Highly stylized Art Nouveau cartouche on Rue Jean-de-La-Fontaine no. 21, Paris, by Hector Guimard, c.1911.jpg.webp) Greek Revival cartouche of a horse tie ring of the Adina and Emil Costinescu House (Strada Polonă no. 4), Bucharest, by Ion D. Berindey, 1911-1915[19]

Greek Revival cartouche of a horse tie ring of the Adina and Emil Costinescu House (Strada Polonă no. 4), Bucharest, by Ion D. Berindey, 1911-1915[19].jpg.webp)

Art Deco cartouche above the entrance columns of the National Diet Building, Kyoto, by Fukuzo Watanabe, 1920-1936

Art Deco cartouche above the entrance columns of the National Diet Building, Kyoto, by Fukuzo Watanabe, 1920-1936

Postmodernism and Retro resuses

At the end of the WW2, with the rise in popularity of the International Style, characterized by the complete lack of any ornamentation, led to the complete abandonment of any ornaments, including cartouches.

They reappear later in some Postmodernism, a movement that questioned Modernism (the status quo after WW2), and which promoted the inclusion of elements of historic styles in new designs. An early text questioning Modernism was by architect Robert Venturi, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966), in which he recommended a revival of the 'presence of the past' in architectural design. He tried to include in his own buildings qualities that he described as 'inclusion, inconsistency, compromise, accommodation, adaptation, superadjacency, equivalence, multiple focus, juxtaposition, or good and bad space.'[20] Venturi encouraged 'quotation', which means reusing elements of the past in new designs. Part manifesto, part architectural scrapbook accumulated over the previous decade, the book represented the vision for a new generation of architects and designers who had grown up with Modernism but who felt increasingly constrained by its perceived rigidities. Multiple Postmodern architects and designers put simplified reinterpretations of the elements found in Classical decoration on their creations. However, they were in most cases highly simplified, and more reinterpretations than true reuses of the elements intended. Because of their complexity, cartouches were extremely rarely used in Postmodern architecture and design.[21]

Cartouches enjoyed more popularity in Retro style of the 21st century, through designs inspired mainly by the 18th and 19th centuries.

.jpg.webp) Postmodern mascarons in cartouches spilling water in Piazza d'Italia, New Orleans, USA, by Charles Moore, 1978[22]

Postmodern mascarons in cartouches spilling water in Piazza d'Italia, New Orleans, USA, by Charles Moore, 1978[22] Cartouche with an Art Nouveau-inspired print on a Vans t-shirt, unknown fashion designer and illustrator, c.2021, print on textile

Cartouche with an Art Nouveau-inspired print on a Vans t-shirt, unknown fashion designer and illustrator, c.2021, print on textile

See also

- Tondo (art): round (circular)

- Medallion (architecture): round or oval

- Architectural sculpture

- Cartouche (cartography)

- Cartouche

- Resist: a technique in ceramics to highlight cartouches, etc.

- Console (heraldry)

Footnotes

- ↑ Ching, Francis D. K. (1995). A Visual Dictionary of Architecture. New York: John Wiley and Sons. p. 183. ISBN 0-471-28451-3.

- ↑ Fullerton, Mark D. (2020). Art & Archaeology of The Roman World. Thames & Hudson. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-500-051931.

- ↑ Eastmond, Anthony (2013). The Glory of Byzantium and early Christendom. Phaidon. p. 46. ISBN 978 0 7148 4810 5.

- ↑ Eastmond, Anthony (2013). The Glory of Byzantium and early Christendom. Phaidon. p. 36. ISBN 978 0 7148 4810 5.

- ↑ Irv Graham. "Longquan Ware Vase – The Percival David Collection". chineseantiques.co.uk. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ↑ Robertson, Hutton (2022). The History of Art - From Prehistory to Presentday - A Global View. Thames & Hudson. p. 784. ISBN 978-0-500-02236-8.

- ↑ "Tombeau du coeur de François Ier, roi de France". pop.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ↑ "Maison". pop.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ↑ Bresc-Bautier, Geneviève (2008). The Louvre, a Tale of a Palace. Musée du Louvre Éditions. p. 28. ISBN 978-2-7572-0177-0.

- ↑ Hopkins 2014, p. 82.

- ↑ Robertson, Hutton (2022). The History of Art - From Prehistory to Presentday - A Global View. Thames & Hudson. p. 870. ISBN 978-0-500-02236-8.

- ↑ Irving, Mark (2019). 1001 BUILDINGS You Must See Before You Die. Cassel Illustrated. p. 217. ISBN 978-1-78840-176-0.

- ↑ "Espace Bellechasse". abcsalles.com. Retrieved 27 August 2023.

- ↑ Marinache, Oana (2019). ArhiTur - Bulevardul Colțea - Bulevardul Lascăr Catargiu (in Romanian). Editura Istoria Artei. p. 21.

- ↑ Mariana Celac, Octavian Carabela and Marius Marcu-Lapadat (2017). Bucharest Architecture - an annotated guide. Ordinul Arhitecților din România. p. 90. ISBN 978-973-0-23884-6.

- ↑ "Boulangerie". pop.culture.gouv.fr. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ↑ Croitoru-Tonciu, Monica (2022). Alfred Popper - 1874-1946 - (re)descoperirea unui arhitect (in Romanian). SIMETRIA. p. 30. ISBN 978-973-1872-51-3.

- ↑ Woinaroski, Cristina (2013). Istorie urbană, Lotizarea și Parcul Ioanid din București în context european (in Romanian). SIMETRIA. p. 218. ISBN 978-973-1872-30-8.

- ↑ Woinaroski, Cristina (2013). Istorie urbană, Lotizarea și Parcul Ioanid din București în context european (in Romanian). SIMETRIA. p. 205. ISBN 978-973-1872-30-8.

- ↑ Watkin, David (2022). A History of Western Architecture. Laurence King. p. 660. ISBN 978-1-52942-030-2.

- ↑ Hopkins 2014, p. 200, 203.

- ↑ Hodge 2019, p. 47.