Carnivals, known as carnavales, charangas, or parrandas, have been vibrant public celebrations in Cuba since at least the 17th century, with the Carnaval of Santiago de Cuba holding a special place among Cubans (Pérez I 1988:20).

The history of Carnival in Cuba is a complex interplay of diverse influences and interests. While some may emphasize its continuous historical connection with Africa, a deeper examination reveals that the carnival culture in Cuba has evolved over time, drawing from multicultural Cuban history.[1] Carnival reflects the dynamic power dynamics within Cuban society and serves as an expression of shifting power negotiations.

It is essential to recognize that carnival in Cuba is not solely rooted in African traditions but is a multifaceted cultural amalgamation that reflects the country's diverse heritage. Through the centuries, Cuban carnival has evolved, incorporating various elements from African, European, and other cultural influences, resulting in a unique and vibrant celebration that resonates with the Cuban people.

Origin of the Carnaval: Mamarrachos

Carnival, known as "carnaval" in Spanish, is a pre-Lenten festival that gained popularity in Spain during the middle of the 10th century. It was likely brought to Cuba by Hispanic colonists (Reference: Pérez I 1988:15), and has since become the foundation for traditional celebrations in the country, such as the Carnaval habanero. However, the Carnaval of Santiago de Cuba, which evolved from the former summer festivals known as the "mamarrachos" (Brea and Millet 1993:193),[2] is distinct from the pre-Lenten carnival celebrated in February or March.

The mamarrachos were festive events held on various days in summer, including June 24 (St. John's [Midsummer] Day), June 29 (St. Peter's Day), July 24 (St. Christine's Day), July 25 (St. James the Apostle's Day), and July 26 (St. Anne's Day). These celebrations were not religious in the liturgical sense they were intended to be. Instead, they were public occasions for jubilation and amusement, with festivities centered around music, dancing, and the consumption of alcoholic beverages (Pérez I 1988:22, 24, note 1).

The precise origins of the mamarrachos are unclear, and the term "mamarrachos" itself does not appear in records until 1757. However, there are earlier records of the festivals dating back to 1679, and they likely existed even before that (Reference: Pérez I 1988:24, 28). Two theories exist about their origin. One suggests that they gradually extended from more traditional European festivals, including carnaval,[3] while the other links the mamarrachos to the procession of St. James the Apostle, the patron saint of Santiago de Cuba (Reference: Pérez I 1988:21; del Carmen et al. 2005). These theories may not be mutually exclusive (see also "Winter Carnival vs. Summer Carnival" below).

A typical 19th-century Mamarrachos

During the 19th century, the mamarrachos festivals in Santiago de Cuba were characterized by a variety of activities. These included animal-drawn carriages, bonfire building, pilgrimages to sanctuaries with torches, and the consumption of beverages like aguardiente, "Yara" rum, fruit juices, chocolate, soup, beer, and coffee. People also dressed in costumes and masks,[4] attended masked balls with music performed by the orquesta típica playing contradanzas, danzas, danzones, rigadoons, and waltzes. Refreshments were sold at mesitas, which were tables covered with awnings. Festival-goers engaged in versification with cantos de pullas, mocking songs often improvised by comparsas, small groups of revelers. The comparsas would also participate in spontaneous parades, and the festivities culminated with a grand parade called montompolo on the last day of mamarrachos, bidding farewell to the celebration (Reference: Pérez I 1988:132-5, etc.).

Comparsa

The Carnaval of Santiago de Cuba is marked by various important festivities, with the parades or street performances of comparsas being the most significant. The term "comparsa" originates from the Italian word "comparire," meaning "to appear briefly" like a walk-on appearance in a theater. In the context of carnival or other festivals, comparsas refer to groups of musicians and dancers who perform in the streets.

Records of comparsas in connection with the mamarrachos of St. John and St. Peter date back to 1679, and the first recorded comparsa, "Los Alegrones," was active in 1757. During the 19th century, there were 46 active comparsas, each with its unique costumes and themes, as documented by Cuban historian Nancy Pérez.

In the 19th century, Pérez categorized the Santiagueran comparsas into two types: paseos and congas.[5][6] Paseos were distinguished by their orchestral music, scenography, and choreographed dance steps. They were usually accompanied by mobile versions of the danzoneras or orquestas típicas, or sometimes Spanish military bands.[7] On the other hand, congas were large gatherings of dancers who followed a selected theme, dancing rhythmically to mainly percussion instruments like drums and metal pans.

Congas mainly comprised humble individuals with limited means, while paseos tended to be more extravagant, requiring greater capital. The congas were known for their inventiveness[8] and played a pivotal role in shaping the unique music and dance styles that define the Carnaval of Santiago de Cuba (see Conga).

Attitude of the colonial authorities to the Mamarracho tradition

During the colonial period, the mamarrachos were generally tolerated by the authorities in Santiago de Cuba. However, there were instances when they were forbidden due to abuses and disturbances caused during the festivities. For example, in 1788, restrictions were imposed due to abuses, and in 1794, because of the moral and physical damage they caused. In 1815 and 1816, the events were banned to prevent drunken coach-drivers and disorderly conduct among participants. In subsequent years, the mamarrachos faced restrictions for fear of disorder and to maintain the city's tranquility.[9]

Despite the tolerance, there were regulations on paper to govern the mamarrachos. In 1679, black slaves were prohibited from participating in comparsas with masked members, and black freedmen were not allowed to conceal their faces with paint or masks to prevent potential violent conflicts. In 1841, a proclamation by the Spanish Governor prohibited certain actions during the paseo, including riding horses or vehicles too fast, ridiculing others through speech, song, or verse, and wearing offensive costumes. Comparsa directors were required to seek permission before entering private properties,[10] and law officers were instructed to arrest violators, regardless of their status, and anyone carrying offensive arms under their costumes.

Similar proclamations were repeated in subsequent years until the end of the colonial period, reinforcing the regulation of the mamarrachos' festivities.

Opposition to the Mamarrachos

Throughout its history, the celebration of mamarrachos in Santiago de Cuba has been a subject of debate, with some advocating for regulation, reform, or even abolition of the festivities. As early as 1879, there were motions made in the Municipal Council to address the concerns surrounding mamarrachos:

One proposal called for the complete prohibition of mamarrachos,[11] as they were seen as ridiculous and detrimental to the city's moral and material interests. Another, more moderate suggestion, was to limit mamarrachos to specific days and locations and impose restrictions on offensive behavior and costumes.

Amidst the discussions, there were different perspectives on how to treat the mamarrachos tradition. Some wanted to preserve and civilize it, drawing parallels with European carnival celebrations. They proposed eliminating elements considered uncivilized, such as the use of dirty shoe polish or indecorous African elements. Instead, they aimed to educate and enlighten participants about appropriate behavior.

An editorial from La Independencia in 1908 expressed admiration for European traditions and suggested the need for purification of the mamarrachos by removing African and Afro-Cuban influences. However, it highlighted the authorities' limited efforts in regulating the festivities through repeated proclamations.

Winter Carnival vs. Summer Carnival

Mamarrachos, a traditional celebration in Santiago de Cuba, took place well after the sugar cane harvest, allowing unemployed workers, mainly African and mulatto slaves and freedmen, to participate in the festivities.[12] Originally intended as a period of rest and diversion for the lower classes, mamarrachos were permitted by Spanish colonial authorities, who believed it would distract the slaves from more subversive activities.

In the present day, Carnival is celebrated on July 18-27 in Havana, Matanzas, and Santiago de Cuba, in honor of the Revolution, with the final parade held on July 26.. In the past, there were two types of Carnival celebrations in Santiago. The Winter Carnival, held in February or March and supported by exclusive organizations, catered to the well-to-do minority of the population with European-style masquerade balls.[13]

On the other hand, the Summer Carnaval or Carnaval Santiaguero originated during the slavery period and catered to the lower classes, including African and Afro-Cuban influences. As the unemployed sugar and coffee workers, sponsored by local industries, participated in the summer festivities, the popularity of Summer Carnaval increased.[14] By the 1940s and 1950s, Carnaval in Santiago and Havana became more commercialized.[15]

Attempts were made to civilize the traditional festivities, and Winter Carnival was created as a more "civilized" counterpart to the traditional summer celebrations. However, Winter Carnival did not last long due to its individualistic nature. The term "carnaval" eventually replaced other names for the celebrations, such as mamarrachos or mascaradas, despite objections from traditionalists who preferred the original term "Los Mamarrachos."[16]

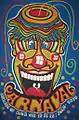

Posters representing Carnival of Santiago de Cuba

Carnival 1974

Carnival 1974 Carnival 1980

Carnival 1980 Carnival 1981

Carnival 1981 Carnival 1981

Carnival 1981 Carnival 1982

Carnival 1982 Carnival 1983

Carnival 1983

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Judith, Bettelheim. “African Arts.” Negotiations of Power in Carnaval Culture in Santiago de Cuba. UCLA James S. Coleman African Studies Center: April 1991. 68. Print.

- ↑ Sg. and pl.; from Arabic muharrig “clown.” Various meanings in modern Castilian. “Historically, a group of masked or costumed persons who danced rhythmically in the streets following the parrandas or comparsas during the major festivals in July. These characters originally gained such importance in the Santiago carnival that carnival itself became identified as the Fiesta de mamarrachos, and was thus called until the present century.” (Brea and Millet 1993:193)

- ↑ Fernando Ortíz, in "Las comparsas populares del Carnaval habanero" in Estudios Afrocubanos, vol, V, La Habana, 1954-6, p.132, observed that there is a chain of festivals that extends from Christmas Eve to the Spring Equinox, probably having their ancient origins in agricultural rites. Ortíz was referring specifically to the city of Havana, but these festivals are common to all Spanish-speaking cultures.

- ↑ Costumes were imported or made locally and worn by well-to-do attenders of masked balls. Parodies of famous people, living or dead, dominos, harlequins, etc. were popular. Poor people wore normal clothes and smeared their faces with colored greases or pastes, or wore inexpensive masks (Pérez I 1988:133-4).

- ↑ A third type, the comparsa carabalí, was not mentioned in documents until 1902 (Pérez I 1988:166), but "according to the testimony of some descendants of the founders of the Cabildo [Carabalí Isuama], it existed before the later stages of the colonial era." (Pérez II 1988:174, note 2).

- ↑ In both written sources and spoken language, the terms “comparsa,” “conga” and “paseo” may be used in an inconsistent way (Pérez I 1988:136).

- ↑ The tajona was a type of parade music and dance of the Haitianos or Haitian-Cubans (Brea and Millet 1993:200).

- ↑ A conguero is someone who participates in a conga as a musician or dancer.

- ↑ Pérez says: "The prohibitions of fiestas in 1869 reflect the prevailing state of [The Ten Years’] war which, though not stated explicitly, can be seen in the interest of the authorities in maintaining the ‘tranquility’ of the population." Pérez I 1988:125, note 50.

- ↑ It was the custom for comparsas and relaciones to enter the houses of the well-to-do and perform in hopes of getting a tip. Some people took advantage of the custom by forming groups who rehearsed very little, forced their way into people’s houses, gave a perfunctory performance and then urged the hosts to give them as large a tip as possible (Pérez I 1988:95)

- ↑ See, for example, an article by José Mas y Perez, dated 1884, but from a reproduction in La Independencia of July 24, 1922, cited in Pérez I 1988:113-4.

- ↑ First mentioned in 1679, but certainly occurring before that date (Pérez I 1988:24).

- ↑ A pre-Lenten carnival could not, of course, be attended by seasonal workers, most of whom were Afro-Cubans, because it would fall during the zafra.

- ↑ Judith, Bettelheim., 71.

- ↑ Judith, Bettelheim., 71.

- ↑ Raul Ibarra in Oriente, June 20, 1947; “Las Fiestas de los Mamarrachos,” (cited in Pérez II:176).

References

- Judith, Bettelheim. "Negotiations of Power in Carnaval Culture in Santiago de Cuba." African Arts, Ed. James S. Coleman. 24 vols. (April 1991): 25 Jan. 2010. African Studies Center, 1991.

- Dale, Olsen A., Daniel Sheehy E. "Cuba." The Encyclopedia of Cuba. Ed. Henken Ted. 2nd vols. California: Duke University Press, 2003.

- Figueredo, D.H. "Carnivals." Dictionary of the Middle Ages. Ed. Dale A. Olsen. 2 vols. New York: Garland, 1998. Print. 506.

- William, Luis. Culture and Customs of Cuba. Wesport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000.

- Bettelheim, Judith. "Cuban Festivals." An Illustrated Anthology. New York: Garland Publishing, 1993: 14.

- Bettelheim, Judith. 1993. Carnival in Santiago de Cuba. In Cuban Festivals (2001), ed., Judith Bettelheim. Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers. ISBN 976-637-001-X

- Brea, Rafael and Millet, José. 1993. Glossary of Popular Festivals. In Cuban Festivals (2001), ed., Judith Bettelheim. Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers. ISBN 976-637-001-X

- del Carmen, Maria, Hernández, Yohemis and González, Carlos Alberto (2005). "Carnaval Santiago". Dirección municipal de Santiago de Cuba. Archived from the original on 2007-02-24. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Pérez, Nancy. 1988. El Carnaval Santiaguero, Tomo I. Santiago de Cuba: Editorial Oriente.

- ____________. 1988. El Carnaval Santiaguero, Tomo II. Santiago de Cuba: Editorial Oriente.

Discography

- Carnaval à Santiago de Cuba; Le Chant du Monde LDX-A-4250

- Carnaval in Cuba; Folkways Records FW04065 (1981) - the Smithsonian Folkways catalog page for this item has samples of music from the Carnaval of Santiago de Cuba.