| Part of a series on |

| Climate change mitigation |

|---|

Carbon accounting (or greenhouse gas accounting) is a framework of methods to measure and track how much greenhouse gas (GHG) an organization emits.[3] It can also be used to track projects or actions to reduce emissions in sectors such as forestry or renewable energy. Corporations, cities and other groups use these techniques to help limit climate change. Organizations will often set an emissions baseline, create targets for reducing emissions, and track progress towards them. The accounting methods enable them to do this in a more consistent and transparent manner.

The main reasons for GHG accounting are to address social responsibility concerns or meet legal requirements. Public rankings of companies, financial due diligence and potential cost savings are other reasons. GHG accounting methods can help investors better understand the climate risks of companies they invest in. Accurate accounting methods also aid corporate and community net-zero goals. Many governments around the world require various forms of reporting. There is some evidence that programs that require GHG accounting help to lower emissions.[4] Markets for buying and selling carbon credits depend on accurate measurement of emissions and emission reductions. These techniques can help to understand the impacts of specific products and services. They do this by quantifying their GHG emissions throughout their lifecycle. This encourages purchasing decisions that are environmentally friendly.

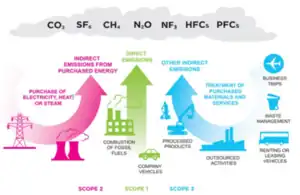

These techniques can be used at different scales, from those of companies and cities, to the greenhouse gas inventories of entire nations. They typically involve a combination of measurements, calculations, estimates, and reporting. A variety of standards and guidelines can apply, including Greenhouse Gas Protocol and ISO 14064. These often organize emissions into three categories. The Scope 1 category covers direct emissions from an organization's facilities. Scope 2 covers emissions from electricity purchased by the organization. Scope 3 covers other indirect emissions, including those from general suppliers[5] and use of the organization’s products.[6]

There are a number of challenges in creating accurate accounts of greenhouse gas emissions. Scope 3 emissions, in particular, can be difficult to estimate. In project accounting, additionality and double counting issues can affect the credibility of renewable energy and forest preservation efforts. These limitations can, in turn, impact perceptions of progress on climate change. Methods are being developed to provide accuracy checks on accounting reports from companies and projects. Organizations like Climate Trace are now able to check reports against actual emissions via the use of satellite imagery and AI techniques.[7]

Origins

Initial efforts to create greenhouse gas (GHG) accounting methods were largely at the national level. In 1995, the United Nations climate program required developed countries to report annually on their emissions from six types of industry. Two years later, the Kyoto protocol defined the greenhouse gases that are the focus of today's accounting methods. These are carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide, sulfur hexafluoride, nitrogen trifluoride, hydrofluorocarbons and perfluorocarbons. These actions raised awareness about the importance of accurate GHG emission estimates.[8][9]

In 1998 the World Resources Institute (WRI) and World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) began work to develop a protocol to support this goal. They published the first version of Greenhouse Gas Protocol in September 2001.[10] It establishes a "comprehensive, global, standardized framework for measuring and managing emissions from private and public sector operations, value chains, products, cities, and policies".[11] The corporate protocol divides an organization's emissions into three categories. Scope 1 covers direct emissions from an organization's facilities. Scope 2 covers emissions from generating electricity purchased by the organization. Scope 3 covers other indirect emissions.[5]

Other initiatives since then have helped promote corporate and community participation in GHG accounting. The Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) began in the UK in 2002, and is now a multinational group, with thousands of companies disclosing their GHG emissions.[12] The Science Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) formed in 2015 as a collaboration between CDP, WRI, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), and the United Nations Global Compact (UNGC). Its goal is to establish science-based environmental target setting as a standard corporate practice.[13]

Since the 2015 Paris Agreement there has been an increased focus on standards for financial risk from GHG emissions. The Task Force on Climate Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) formed as a follow-up to the Paris Agreement. It established a framework of recommendations on the types of information that companies should disclose to investors, lenders, and insurance underwriters.[14] More recently, governments such as the EU and US have developed regulations that cover corporate financial disclosure requirements and the use of accounting protocols to meet them.[15][16]

Participation in greenhouse gas accounting and reporting has grown significantly over time. In 2020, 81% of S&P 500 companies reported Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions.[17] Globally, over 22,000 companies disclosed data to CDP in 2022.[18]

Drivers

Internal company drivers

A variety of business incentives drive corporate carbon accounting. These include rankings alongside other companies,[17] managing climate change related risks, investment due diligence, shareholder and stakeholder outreach, staff engagement, and energy cost savings. Accounting for greenhouse gas emissions is often seen as a standard practice for business.[19][20]

Governmental requirements

Legal requirements provide another type of driver. These are usually created through specific laws on reporting, or within broader environmental programs. Emissions trading markets also depend on accounting and reporting protocols.[21] In 2015 more than 40 countries had some type of reporting requirement in place.[22]

The EU's Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) is part of the European Green Deal. It is intended to make EU countries carbon neutral by 2050. This directive will require many large companies and companies with securities listed on EU-regulated markets to disclose a broad array of ESG information, including GHG emissions.[16] The UK's Environmental Reporting Guidelines update and clarify requirements in earlier laws that required companies to report information on GHG emissions.[23][24] In the US the Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program (GHGRP) requires facility (as opposed to corporate) based reporting of GHG emissions from large industrial facilities. The program covers a total of 41 industrial categories.[25]

Recent regulations are also coming from agencies that traditionally have had a financial focus. The US Security Exchange Commission (SEC) proposed a rule in 2022 to require all public companies, regardless of size, to report Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions. Larger companies would be required to disclose Scope 3 emissions only if they are material to the company, or if the company has set an emissions target that includes Scope 3.[26] Japan's Financial Services Agency's (FSA) also issued rules in 2022 that require financial disclosure of climate related information. These may cover around 4,000 companies, including those listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange.[27]

Government procurement requirements have also begun to incorporate GHG reporting requirements. In 2022 both the US and the UK governments issued executive type orders that require this practice.[28][29]

Emission trading schemes in various countries also play a role in promoting GHG accounting, as do international carbon offset programs. The European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) is a cap-and-trade system where a limit is placed on the right to emit specified pollutants over an area, and companies can trade emission rights within that area.[30] EU ETS is the second largest trading system in the world after the Chinese national carbon trading scheme, covering over 40% of European GHG emissions.[31] Greenhouse Gas Protocol is cited in its guidance documents.[32][33] California's cap-and-trade program operates along similar principles.[34] International offset programs also contain requirements for quantifying emission reductions from specific project. The CDM has a detailed set of monitoring, reporting, and verification procedures,[35] as does the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+) program.[36] As of 2022, similar procedures to document project reductions under Article 6 of the Paris agreement are yet to be worked out .[37]

Non-governmental organization programs

Many NGOs have developed programs that both promote GHG accounting and reporting, and help define its features. The Carbon Disclosure project allows a range of protocols for reporting to it.[38] Most companies report GHG emissions to CDP using Greenhouse Gas Protocol or a protocol based on it.[39] The Science Based Targets initiative cites Greenhouse Gas Protocol guidance as part of its criteria and recommendations.[40] Similarly, the TCFD cites Greenhouse Gas Protocol in its recommended metrics and targets.[41]

Frameworks and standards

Many of today's carbon accounting standards have incorporated principles from the 2006 guidelines for greenhouse gas inventories that were created by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).[42] Those most consistently applied include transparency, accuracy, consistency, and completeness. The IPCC principle of comparability, for example amongst organizations, is less widely applied,[43] though techniques to support this goal are mentioned throughout Greenhouse Gas Protocol's corporate standard.[44]

These standards typically cover the greenhouse gases first regulated under the Kyoto Protocol.[9] They operate in two distinct manners. Attributional accounting allocates emissions to specific organizations or products, and measures and tracks them over time. Consequential accounting methods measure the difference from a specific change, like a GHG reduction project.[45]

Corporate/local government standards

Corporations and facilities use a variety of methods to track and report GHG emissions. These include those from Greenhouse Gas Protocol, the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosure, the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, the Global Reporting Initiative, the Climate Disclosure Standards Board, the Climate Registry, as well as several industry specific organizations.[46] CDP lists an even broader set of acceptable methods for reporting in its guidance.[47] Standards for cities and communities include the Global Protocol for Community Scale Greenhouse Gas Inventories and the ICLEI U.S. Community Protocol. This covers cities and communities in the US.

Greenhouse Gas Protocol

GHG Protocol is a group of standards that are the most common in GHG accounting.[48] These standards reflect a number of accounting principles, including relevance, completeness, consistency, transparency, and accuracy.[49] The standards divide emissions into three scopes.

Scope 1 covers all direct GHG emissions within a corporate boundary (owned or controlled by a company).[5] It includes fuel combustion, company vehicles and fugitive emissions.[50] Scope 2 covers indirect GHG emissions from consumption of purchased electricity, heat, cooling or steam.[51] As of 2010, at least one third of global GHG emissions are Scope 2.[52]

Scope 3 emission sources include emissions from suppliers and product users (also known as the "value chain"). Transportation of goods, and other indirect emissions are also part of this scope.[53] Scope 3 emissions often represent the largest source of corporate greenhouse gas emissions, for example the use of oil sold by Aramco.[54] These were estimated to represent 75% of all emissions reported to the Carbon Disclosure Project, though that percentage varies widely amongst business sectors.[55] In 2022 about 30% of US companies reported Scope 3 emissions.[56] However, the International Sustainability Standards Board is developing a recommendation that Scope 3 emissions be included as part of all GHG reporting.[57] There are 15 Scope 3 categories. Examples include goods or services an organization purchases, employee commuting, and the use of sold products. Not every category is relevant to all organizations.[58]

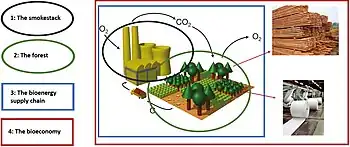

WRI is currently developing a Land Sector and Removals Standard for its corporate reporting guidelines.[59] This will include emissions and removals from land management and land use change; biogenic products; and carbon dioxide removal technologies.

ISO 14064

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) published ISO 14064 standards for greenhouse gas accounting and verification in 2006.[60] ISO, WRI and WBCSD worked together to ensure consistency amongst the ISO and Greenhouse Gas Protocol standards.[61] ISO 14064 is based on Greenhouse Gas Protocol.[62] Part 1 (ISO 14064-1:2006) specifies principles and requirements for estimating and reporting GHG emissions and removals.[63] Part 3 (ISO 14064-3:2006) provides guidance for conducting and managing the verification of GHG reporting.[64]

PAS 2060

PAS 2060 is a standard that describes how organizations can demonstrate carbon neutrality. It was developed by the British Standards Institute and published in 2010. Under PAS 2060 GHG estimates should include 100% of Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions, plus all Scope 3 emissions that contribute more than 1% of the total footprint. Organizations must also develop a Carbon Management Plan which contains a public commitment to carbon neutrality along with a reduction strategy. This strategy should include a time scale for achieving neutrality, specific targets for reductions, how those reductions will be achieved and how residual emissions will be offset.[65]

EPA Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)’s Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program (GHGRP) requires facility and supplier based reporting for many categories of emissions sources. The program includes guidelines for how emissions are to be estimated and reported. Facilities are required to report (1) combustion emissions resulting from burning fossil fuels or biomass (such as wood or landfill gas); and (2) other emissions from industrial processes, such as chemical reactions from iron and steelmaking, cement, or petrochemicals. Categories of suppliers that must report include coal and natural gas, petroleum products, as well as suppliers of CO2 and other industrial GHGs. Monitoring methodologies are more specific than GHG Protocol or ISO 14064, and require the use of continuous monitoring systems, mass balance calculations, or default emission factors.[66] EPA uses the facility-level and supplier data to help prepare the annual Inventory of U.S. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Sinks, which is submitted to the United Nations.[67]

Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures

Created in 2015, the Task Force on Climate Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) provides information to investors about what companies are doing to mitigate the risks of climate change. TCFD's disclosure standard for companies covers four thematic areas. These are governance, strategy, risk management, and metrics and targets.[41] There are also several principles TCFD emphasizes in its guidance. Disclosures should be representative of relevant information; specific and complete; as well as clear, balanced, and understandable. In addition, estimates also need to be consistent over time; comparable amongst companies within a sector industry or portfolio; reliable, verifiable, and objective; and timely.[41] The metrics and targets portion of the standard requires measurement and disclosure methods based on GHG Protocol.[41] The TCFD's standard specifies that companies should disclose all Scope 1 and 2 emissions regardless of their material impacts on the company. Scope 3 emission reporting is dependent on whether they are "material", but TCFD recommends they be included.[41]

Protocols for cities/communities

The Global Protocol for Community-Scale Greenhouse Gas Inventories (GPC) is the result of a collaborative effort between the GHG Protocol at World Resources Institute (WRI), C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group (C40), and Local Governments for Sustainability (ICLEI).[68] It requires a community to first identify the inventory boundary, such as an administrative boundary for a city or county.[69] The protocol focuses on six main activity sectors. These are stationary energy; transportation; waste; industrial processes and product use; agriculture, forestry and other land use. Emissions occurring outside the geographic boundary that are a result of a jurisdiction's activities are also included.[69] To distinguish between emissions that occur within a city boundary and outside, the protocol uses the Scope 1, 2 and 3 definitions in GHG Protocol.[69] Communities report emissions by gas, scope, sector and subsector using two options. One is a framework that reflects a more traditional Scope 1, 2, and 3 assessment. Another is more focused on activities taking place within that community, and excludes categories such as waste generated outside of it.[70]

The U.S. Community Protocol developed by ICLEI–Local Governments for Sustainability USA also emphasizes the use of geographic boundaries rather than corporate boundaries. It recommends an approach focused on specific emission sources and activities rather than the more commonly used Scope 1, 2 and 3 framework to calculate emissions.[71] The guidance suggests communities consider the stories they wish to convey about community emissions, and what reporting methods will help tell those stories.[72] The guidance covers five basic emissions generating activities. These are use of electricity by the community; use of fuel in residential and commercial stationary combustion equipment; on‐road passenger and freight motor vehicle travel; use of energy in drinking water and wastewater treatment and distribution; and generation of solid waste by the community.[72] Reporting guidance covers a variety of approaches, and organizations can include one or more of them. These include GHG activities and sources over which a local government has significant influence; GHG activities of community interest; household consumption inventories; and an inventory that incorporates the GHG emissions (and removals) from land use.[72] GHG reports from cities have been found to vary widely, and often show lower emissions than those from independent analyses.[73]

Consumption-based methods, such as PAS 2070, provide another perspective on community greenhouse gas emissions. These clarify the difference between GHG emissions from sources within a community boundary, and GHG emissions from goods and services that are used by residents, but produced outside the community.[74] These consumption-based estimates can often be much greater than those from sources solely within a community.[75]

Product accounting standards

Product accounting methods are part of a broader set of Life Cycle Assessment approaches that include Product Carbon Footprints. These focus on the single issue of climate change. They can be used for either a product or a service. Related standards include ISO 14067, PAS 2050, and GHG Protocol Product Standard.[76]

GHG Protocol for Products builds on the framework of requirements in the ISO 14040 and PAS 2050 standards. It is similar to GHG Protocol Scope 3, but focused on life cycle/value chain impacts for a specific product.[77] The same five accounting principles apply as with the Corporate Standard.[78] Steps include setting business goals, defining analysis boundaries, calculating results, analyzing uncertainties, and reporting.[79] Boundaries for final products are required to include the complete cradle-to-grave life cycle.[80]

The ISO 14067 standard builds largely on other existing ISO standards for LCA.[76] Steps include goal and scope definition, inventory analysis, impact assessment, interpretation, and reporting.[79] For ISO 14067, the life cycle stages that need to be studied in the LCA are defined by a variety of system boundaries. Cradle-to-grave includes the emissions and removals generated during the full life of cycle of the product. Cradle-to-gate includes the emissions and removals up to where the product leaves the organization. Gate-to-gate includes the emissions and removals that arise in the supply chain.[81]

Product footprint analysis can provide insight into GHG contributions throughout the value chain. On average, 45% of total value chain emissions arise upstream in the supply chain, 23% during the company's direct operations, and 32% downstream.[82]

Project accounting standards

Project accounting standards and protocols are typically used to ensure the "environmental integrity" of projects designed to reduce GHG emissions and generate carbon offsets. They support both compliance type programs as well as voluntary markets.[83] Accounting rules cover areas such as monitoring, reporting, and verification, and are designed to ensure that the emission reduction estimates for a project are accurate. Greenhouse Gas Protocol and ISO have specific protocols to accomplish this. Certification organizations also have program requirements can cover project eligibility, certification, and other aspects.[84] Verified Carbon Standard, the Gold Standard, Climate Action Reserve and the American Carbon Registry are among the leading certification organizations doing this work.[85] Project developers, brokers, auditors, and buyers are the other main types of participants.[86]

Several principles help ensure the environmental integrity of carbon offset projects that rely on this family of standards. One key principle is additionality. This depends on whether the project would occur anyway without the funds raised by selling carbon offset credits. For instance, a project would not be considered additional if it is already financially viable due to energy or other cost savings. Similarly, if it would normally be done to meet an environmental law or regulation, it would not be additional. Various kinds of analyses can help evaluate this aspect of a project, though the results are often subjective.[87]

Projects are also judged based on the permanence of reductions over various time horizons. This is important in areas such as forestry projects. They should also be designed to avoid double-counting, where reductions are claimed by more than one organization. Avoiding overestimation of emission reductions is another consideration. Some protocols and standards look to ensure that projects produce social and environmental co-benefits, in addition to emission reductions from the project itself.[88][89]

ISO 14064 Part 2

This standard provides guidance for quantification, monitoring and reporting of GHG reduction activities or removal enhancements. It includes requirements for planning a GHG project, as well as identifying and selecting GHG sources and sinks. It also covers various aspects of GHG project performance.[90]

GHG Protocol standards for projects and policies

The accounting principles in the GHG Protocol for Project Accounting include relevance, completeness, consistency, transparency, accuracy and conservativeness.[91] Like the ISO standard, the protocol's focus is on core accounting principles and impact quantification, rather than the programmatic and transactional aspects of carbon credits. The protocol gives general guidance on applying additionality and uncertainty principles, but does not specifically require them.[92] WRI and WBCSD have also developed additional guidance documents for projects in the land use, forestry, and electric grid sectors.[93] GHG Protocol Policy and Action Standard has similar accounting principles, but these are applied to general programs and policies designed to reduce GHGs.[94]

Verified Carbon Standard (VERRA)

VERRA was developed in 2005, and is a widely used voluntary carbon standard. It uses accounting principles based on ISO 14064 Part 2, which are the same as the GHG protocol principles described above.[95] Allowable projects under VERRA include energy, transport, waste, and forestry. There are also specific methodologies for REDD+ projects.[96] Verra has additional criteria to avoid double counting, as well as requirements for additionality. Negative impacts on sustainable development in the local community are prohibited. Project monitoring is based on CDM standards.[97]

Gold Standard

The Gold Standard was developed in 2003 by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) in consultation with an independent Standards Advisory Board. Projects are open to any non-government, community-based organization. Allowable project categories include renewable energy supply, energy efficiency, afforestation/reforestation, and agriculture (the latter can be difficult - for example soil carbon measurements are depth sensitive[98]). The program's focus includes the promotion of Sustainable Developments Goals. Projects must meet at least three of those goals, in addition to reducing GHG emissions. Projects must also make a net-positive contribution to the economic, environmental and social welfare of the local population. Program monitoring requirements help determine this.[99] The standard certifies additionality based on an evaluation of financial viability or the institutional barriers that a project faces. In some cases additionality is assumed based on the type of project. There are also screens for double counting.[100]

Other applications

In addition to the uses described above, GHG accounting is used in other settings, both regulatory and voluntary.

Renewable energy credits

Renewable Energy Certificates (REC) or Guarantees of Origin (GO) document the fact that one megawatt-hour of electricity is generated and supplied to the electrical grid through the use of renewable energy resources.[101] RECs are now being utilized around the world and are becoming more prevalent. The United Kingdom (U.K.) has used renewable obligation certificates since 2002 in order to ensure compliance with the U.K. Renewables Obligation. In the European Union, Guarantees of Origin are used to describe this practice. Australia has used RECs since 2001. More recently, India set up a REC market.[102]

In the context of GHG accounting, RECs are often used to adjust estimated Scope 2 emissions. In a typical case, a company would calculate its Scope 2 emissions using its electricity consumption and grid emissions factor. Companies that purchase RECs can use them to lower average emissions factors in their accounting. This allows them to report lower emissions while their real electricity consumption stays the same; as the use of a REC does not necessarily mean additional renewable power has been brought to the grid.[103]

National emissions inventories

Data from facility level accounting can improve the overall quality and accuracy of national inventories by providing quality control checks on inventory estimates and through improved emissions factors. This depends in part on what percentage of the sector's emissions the available data covers.[104] In some cases, aggregated facility level data can also be used to update or modify inventory results for certain sectors.[105]

Net Zero goals and GHG disclosure

The Net Zero concept emerged from the Paris Agreement,[106] and has become a feature of both national laws and numerous corporate goals.[107] Race to Zero was developed in 2019 to encourage private companies and sub-national governments to commit to net zero emissions by 2050 at the latest.[108] SBTI created a Net Zero program in 2021 to assist organizations in making this transition. That standard includes restrictions on the use of carbon removals to reach net zero goals.[109] Accurate and comprehensive GHG accounting is considered a key element of for Net Zero transition plans, including the use of protocols such as GHG Corporate Standard.[110][111]

The CDP (formerly the Carbon Disclosure Project) is an international NGO that helps companies and cities disclose their environmental impact.[112] It aims to make corporate accounting and reporting a business norm, and drive GHG disclosure, insight, and action. In 2021, over 14,000 organizations disclosed their environmental information through CDP.[113] CDP's 2022 questionnaire on transition plans includes specific requirements for describing Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions.[114]

Effectiveness

With the growth of GHG reporting, more information is now available to provide rankings of GHG emissions from companies and cities.[115][116] News media have used these rankings to bring attention to those companies.[117] In some instances, such as media coverage[118][119] of the 2017 "Carbon Majors" report by CDP,[120] this particular use of disclosure was shown to be misleading.[121]

Understanding the overall impacts of GHG reporting in reducing an organization's emissions can be difficult.[122] A number of studies have looked at changes in GHG emissions that occur after GHG reporting begins.[123] There is evidence from related programs that self reporting lowers emissions. EPA's Toxic Release inventory is one such example. It has been shown to have had a significant effect in reducing emissions of chemicals once facilities are required to disclose that information.[124]

Recent studies focusing on changes in GHG emissions that result from GHG reporting have shown mixed results. Voluntary carbon reporting itself has often been shown to be ineffective in reducing GHG emissions.[125][126] However, when looking at the additional impact of programs that require GHG emission reporting, studies have shown more of an effect. A recent study of UK reporting requirements showed that they do result in reduced corporate GHG emissions.[4] Analyses of EPA's Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program found that when firms are required to disclose their facility level emissions, it can also lead to a reduction in GHG intensity of their operations, though the evidence for reductions in absolute emissions is less clear.[123][127] One suggestion for the effects of specific GHG reporting requirements is that they inhibit the ability of companies to portray their emissions in a flattering way, and so are forced to actually make changes that lower GHG emissions.[123]

There are some confounding factors involved in this research. These include whether or not the studies are done in places where there is emissions trading, such as the EU ETS. Another variable is whether or not the requirements focus on larger companies that emit more GHGs. In addition, firms that are required to report on facility emissions appear to focus on controlling emissions for their affected facilities, but to then transfer emissions to nonreporting facilities that they also control.[123][127]

Limitations

GHG accounting faces a number of challenges and critical assessments. One category involves how best to determine organizational boundaries and identify inputs and outputs most relevant to emissions. Problems also arise with characterizing uncertainty in emission estimates, and identifying what information materially affects a company's operations, and therefore needs reporting.[128] The use of alternate standards can affect comparability across organizations, as can lack of third party verification.[129]

Accurate reporting of Scope 3 emissions is a particular challenge. These emissions can be several times greater than Scope 1 and 2 emissions. In some cases these are reported inconsistently, depending on whom they are reported to. Lack of high-quality data can also affect the accuracy of Scope 3 estimates for particular categories of upstream and downstream sources that influence Scope 3 estimates.[130] Companies may neglect to include key Scope 3 categories when reporting to organizations such as CDP.[131] As of 2020, only 18% of the constituents of MSCI's global security index reported Scope 3 emissions.[130] There is also evidence that many of the high rate emitters either under-report or do not report at all.[131] Even Scope 3 data from companies that are then analyzed and summarized by third party auditing firms tend to be highly inconsistent.[132] There are also concerns over double counting of Scope 3 emissions as companies work with their value chain partners. Despite the uncertainty of these numbers, Scope 3 estimates are seen by many companies as important for decision making purposes. They are also considered an important tool for investors to better understand climate related risks in their portfolio.[133]

Many companies may also inaccurately estimate the climate benefits of their products. This can happen by failing to account for a product's full life cycle, using inappropriate comparisons, conflating market size with product use, and cherry picking results to skew a portfolio towards those products that have less impacts.[134]

Double counting of GHG emissions or benefits can discredit the information value. Problems created by skewed data collection methods can affect companies, GHG reduction projects, investors, those involved in carbon credits/offsets, and regulatory agencies. It can also distort perceptions of progress in reducing emissions.[135] In corporate accounting, double-counting can reach about 30-40% of emissions in institutional portfolios.[136] However, some accounting methods can still provide organizations with information on how to reduce real emissions.[137]

In trading schemes and regulatory/inventory schemes, double counting presents other problems.[138] For Renewable Energy Certificates, double counting can falsely exaggerate claims about using renewable resources.[139] Double counting of emission reductions can also produce disincentives to use international carbon trading schemes, such as the CDM. Trading participants may be reluctant to purchase credits if the credits are already used by other entities. Double counting of emission reductions could increase the global costs of reducing GHG emissions.[140] It can also make mitigation pledges less comparable. This, in turn, can affect the credibility of the international climate control efforts, and make it more difficult to reach agreements on how to affect the drivers of climate change.[141] Estimating the extent of double counting is difficult. Estimates depend in part on actions taken at various levels to prevent double counting.[140]

In addition to double counting, carbon offsets face a variety of other challenges that affect the quality of the offset. These include additionality, overestimation, and permanence of offsets.[88] News stories in 2021 and 2022 have criticized nature based carbon offsets, the REDD+ program, and certification organizations.[142][143][144] The REDD+ program in particular has been criticized as having a poor history of accounting for its results.[145] However, positive aspects of these programs have also been highlighted.[146]

Current trends

Standards alignment and interoperability

As mentioned in the "Frameworks and standards" section, organizations can use a variety of accounting methods and approaches to estimate and report on GHG emissions. Some standards, such as GHG protocol, have been in existence for more than two decades.[10] Yet efforts continue to better align these standards and create more interoperability among them. For example, the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) has also been established to develop a global baseline of sustainability standards that it hopes will help harmonize sustainability disclosure requirements. In 2022, the ISSB established a working group to enhance compatibility among various corporate disclosure requirements, including the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive and SEC's 2022 disclosure rule.[147]

Although these are all based on the broader elements of the TCFD framework and GHG protocol, they differ in a variety of ways. For example, when the SEC proposal uses the term "material", it is only describing the extent to which reporting on emissions could directly impact a company financially. The CSRD proposal uses a "double materiality" criterion, which takes into consideration impacts on both a company and the public at large. It remains to be seen how these types of issues will be reconciled.[148]

Another trend is an increased convergence between voluntary standards and regulatory requirements. These began with the incorporation of voluntary offsets standards into the California Emission Trading System. More recently, the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) has incorporated guidance from voluntary carbon market standards. It has approved seven such standards as eligible for use by airlines under its program.[149]

Support for net-zero goals

There is also an increased focus on aligning GHG accounting standards with net-zero goals and claims. SBTi launched a net-zero corporate standard in 2021. Companies that pledge to this standard need to have both short term targets as well as targets for 2050.[150] ISO also has a new standard under development, ISO 14068, that supports net-zero goals.[151] It is expected to build on the original net neutrality standard, PAS 2060.[152]

Managing Scope 3 emissions

For the average company, Scope 3 emissions estimates are significantly higher than the level of direct emissions.[153] NGOs such as SBTI are working to address this. If a company's Scope 3 emissions are more than 40% of their total, that company needs a Scope 3 target to meet SBTi standards.[154] However, only about a third of suppliers reporting to CDP as part of their Global Supply Chain program describe specific climate targets.[155]

In some cases, companies are working with their suppliers to set goals for measuring and reducing emission.[156] Other efforts include developing supplier codes of conduct for specific business sectors.[157] Companies may also target specific offset projects within their own Scope 3 supply chains.[158][159] Government agencies have developed guidance on how to engage with suppliers, including basic questionnaires about Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions.[160]

Voluntary carbon markets

The voluntary market is expected to grow tremendously over the next few decades. To date, the Scope 1-3 emissions of the 54 Global Fortune 500 companies that committed to net zero by 2050 or earlier is about 2.5 gigatons of CO2 equivalent.[158] By comparison, the volume of credits traded on the voluntary carbon market was about 300 megatons as of 2021.[161] Global demand for carbon credits could increase up to 15 times by 2030 and 100 times by 2050.[162] Carbon removal projects such as forestry and carbon capture and storage are expected to have a larger share of this market in the future, compared to renewable energy projects.[163]

Alternative validation approaches

Techniques are being developed to use other emission data sets to validate GHG accounting methods. Project Vulcan collects data from a large number of publicly available data sources for the United States such as pollution reporting, energy statistics, power plant stack monitoring, and traffic counts.[165] Using these data, US cities have been found to often underestimate their emissions.[166] Methods that link emissions data with atmospheric measurements can help improve city inventories.[167]

Climate Trace is an independent organization that improves monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV) by publishing point sources of carbon dioxide and methane in near-real-time.[168] Climate Trace has found underreporting of emissions from the oil and gas sector.[169]

See also

References

- ↑ Hills, Karen (20 April 2022). "The Basics of Carbon Markets and Trends: Something to Keep an Eye On | CSANR | Washington State University". Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ↑ "Greenhouse Gas Protocol". World Resources Institute. 2 May 2023. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ↑ "Carbon Accounting". Corporate Finance Institute. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- 1 2 Downar, Benedikt; Ernstberger, Jürgen; Reichelstein, Stefan; Schwenen, Sebastian; Zaklan, Aleksandar (1 September 2021). "The impact of carbon disclosure mandates on emissions and financial operating performance". Review of Accounting Studies. 26 (3): 1137–1175. doi:10.1007/s11142-021-09611-x. hdl:10419/266352. ISSN 1573-7136. S2CID 220061770.

- 1 2 3 Greenhouse Gas Protocol Corporate Accounting 2004, p. 25

- ↑ "Briefing: What are Scope 3 emissions?". 25 February 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2023.

- ↑ Kim, J. "Al Gore helped launch a global emissions tracker that keeps big polluters honest". NPR.org. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ↑ Green 2010, pp. 6–11

- 1 2 LoPucki 2022, p. 416.

- 1 2 Green 2010, p. 11

- ↑ "Greenhouse Gas Protocol". World Resources Institute. Archived from the original on 28 January 2021. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ↑ Patel, Sambhram (23 June 2021). "CDP reporting: What it is, how it creates value, and how to start". Conservice ESG. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ↑ Segal, Mark (23 September 2021). "SBTi Says 80% of Company Climate Commitments are not Science-Based". ESG Today. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ↑ US EPA, OAR (28 November 2022). "Market Developments Around Climate-Related Financial Disclosures". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ↑ Goldstein, Matthew; Eavis, Peter (21 March 2022). "The S.E.C. moves closer to enacting a sweeping climate disclosure rule". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- 1 2 "Emerging EU ESG Requirements: Transatlantic Implications for Multinational Companies". The National Law Review. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- 1 2 LoPucki 2022, p. 409.

- ↑ "A List companies". www.cdp.net. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ↑ The Greenhouse Gas Protocol. USA: World Resources Institute and World Business Council for Sustainable Development. 2004. p. 11. ISBN 1-56973-568-9.

- ↑ Kauffmann, C; Tébar Less, C; Teichmann, D (2012). Corporate Greenhouse Gas Emission Reporting: A Stocktaking of Government Schemes", OECD Working Papers on International Investment, 2012/01. OECD Working Papers on International Investment. OECD Publishing. p. 27. doi:10.1787/5k97g3x674lq-en.

- ↑ Climate Change Disclosure in G20 Countries-Stocktaking of corporate reporting schemes (PDF). Paris: OECD. 2015. pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Singh, Neelam; Longendyke, Lindsey (27 May 2015). "A Global Look at Mandatory Greenhouse Gas Reporting Programs".

- ↑ "SECR explained: Streamlined Energy & Carbon Reporting framework for UK business". Carbon Trust. 20 April 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ↑ "Environmental reporting guidelines: including Streamlined Energy and Carbon Reporting requirements". GOV.UK. 29 March 2019. pp. 26–27. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ↑ US EPA, OAR (22 September 2014). "Learn About the Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program (GHGRP)". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ↑ Colvin, D; Davis, K; Powell, B. "Deep Dive: GHG Reporting Under the SEC's Proposed Climate-Related Disclosure Rule". Fox Rothschild. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ↑ "Japan to require 4,000 companies to disclose climate risks". Nikkei Asia. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ↑ "Federal Supplier Climate Risks and Resilience Proposed Rule | Office of the Federal Chief Sustainability Officer". www.sustainability.gov. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ↑ Mooney, Clair (10 August 2022). "Taking account of carbon reduction plans in the procurement of major government contracts". FIS. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ↑ Agency, Environmental Protection. "EU Emissions Trading System". www.epa.ie. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ↑ Lam, Austin (3 December 2022). "What is an Emissions Trading Scheme and How Does It Work?". Earth.Org. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ↑ Innovation Fund (InnovFund) Call for proposals - Annex C: Methodology for calculation of GHG emission avoidance (PDF). European Commission. 2021. p. 29. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ↑ "Corporate Standard - Greenhouse Gas Protocol". ghgprotocol.org. p. 4. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ↑ "California Cap and Trade". Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ↑ "A Comparison of Carbon Offset Standards - Making Sense of the Voluntary Carbon Market". wwf.panda.org. pp. 49–53. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ↑ "Measuring, Reporting and Verifying (MRV) REDD+ results". redd.mma.gov.br. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ↑ "Article 6 and Voluntary Carbon Markets". Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ↑ "CDP Climate Change 2021 Reporting Guidance". guidance.cdp.net. Section C.5.2. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ↑ "About Us | Greenhouse Gas Protocol". ghgprotocol.org. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ↑ Science Based Targets Initiative 2021, p. 2

- 1 2 3 4 5 Guidance on Metrics, Targets, and Transition Plans. Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. 2021. P 15.

- ↑ Rypdahl, Kristin; Paciornik, N.; Eggleston, S.; Goodwin, J.; Irving, W.; Penman, J.; Woodfield, M. (2006). "Chapter 1 - Introduction to the 2006 Guidelines" (PDF). 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. International Panel on Climate Change. pp. 1.7 to 1.8. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ↑ Gillenwater, Michael (2 January 2022). "Examining the impact of GHG accounting principles". Carbon Management. 13 (1): 550–553. doi:10.1080/17583004.2022.2135238. ISSN 1758-3004. S2CID 253057499.

- ↑ Greenhouse Gas Protocol Corporate Accounting 2004, pp. 56, 65, 76

- ↑ Brander, Matthew (2 January 2022). "The most important GHG accounting concept you may not have heard of: the attributional-consequential distinction". Carbon Management. 13 (1): 337–339. doi:10.1080/17583004.2022.2088402. ISSN 1758-3004. S2CID 249904220.

- ↑ LoPucki 2022, pp. 425–433.

- ↑ "CDP Climate Change 2021 Reporting Guidance". guidance.cdp.net. Section C.5.2. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ↑ "GHG Protocol". climate-pact.europa.eu. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ↑ Greenhouse Gas Protocol Corporate Accounting 2004, pp. 8–9

- ↑ Greenhouse Gas Protocol Corporate Accounting 2004, p. 27

- ↑ Greenhouse Gas Protocol Corporate Accounting 2004, pp. 27–29

- ↑ Sotos, Mary (2015). GHG Protocol Scope 2 Guidance (PDF). World Resources Institute. p. 6. ISBN 978-1-56973-850-4. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ↑ "Corporate Value Chain (Scope 3) Accounting and Reporting Standard". Greenhouse Gas Protocol. Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 28 February 2016.

- ↑ "Aramco's Net-Zero Plan Will Have Net-Zero Impact Before 2035". Bloomberg.com. 21 June 2022. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ↑ CDP Technical Note: Relevance of Scope 3 Categories by Sector (PDF) (Report). Carbon Disclosure Project. 2022. p. 6. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ↑ Bokern, D. (9 March 2022). "Reported Emission Footprints: The Challenge is Real". MSCI. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ↑ Molé, P. (1 November 2022). "ISSB Votes to Include Scope 3 Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emission Disclosures in Updates to Draft Standards". VelocityEHS. Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ↑ Barrow, Martin; et al. (2013). "Technical Guidance for Calculating Scope 3 Emissions" (PDF). Greenhouse Gas Protocol. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 August 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ↑ "Land Sector and Removals Guidance | Greenhouse Gas Protocol". ghgprotocol.org. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ↑ "New ISO 14064 standards provide tools for assessing and supporting greenhouse gas reduction and emissions trading (2006-03-03) - ISO". www.iso.org. Archived from the original on 22 April 2014. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ↑ Green 2010, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Wintergreen, J; Delaney, T (2007). ISO 14064, International Standard for GHG Emissions Inventories and Verification (PDF). 16th Annual Emissions Inventory Conference. Raleigh, NC: EPA. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- ↑ "ISO 14064-1:2006 - Greenhouse gases -- Part 1: Specification with guidance at the organization level for quantification and reporting of greenhouse gas emissions and removals". www.iso.org. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ↑ "ISO 14064-3:2006 - Greenhouse gases -- Part 3: Specification with guidance for the validation and verification of greenhouse gas assertions". www.iso.org. 9 December 2015. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ↑ "PAS 2060: The ideal standard for carbon neutrality" (PDF). ecoact. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ↑ "Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program: Emission Calculation Methodologies" (PDF). EPA. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ↑ "EPA's Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program". Congressional Research Service. November 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2022.

- ↑ Greenhouse Gas Protocol 2021, p. 26

- 1 2 3 Greenhouse Gas Protocol 2021, p. 10

- ↑ Greenhouse Gas Protocol 2021, p. 39

- ↑ USA, ICLEI (12 June 2015). "US Community Protocol". icleiusa.org. p. 17. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- 1 2 3 USA, ICLEI (12 June 2015). "US Community Protocol". icleiusa.org. p. 20. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ↑ Gurney, Kevin Robert; Liang, Jianming; Roest, Geoffrey; Song, Yang; Mueller, Kimberly; Lauvaux, Thomas (2 February 2021). "Under-reporting of greenhouse gas emissions in U.S. cities". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 553. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12..553G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20871-0. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7854656. PMID 33531471. S2CID 231778063.

- ↑ Wiltshire, Jeremy; Doust, Michael (2013). "Preview". PAS 2070:2013 - Specification for the assessment of greenhouse gas emissions of a city (PDF). BSI Standards Limited. p. iii. ISBN 978-0-580-86536-7.

- ↑ The Future of Urban Consumption in a 1.5°C World (PDF). C40 Cities. 2019. fig.3, p.40.

- 1 2 De Schryver, An; Zampori, Luca (January 2022). "Product Carbon Footprint standards: which one to choose?". PRé Sustainability. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ↑ Bhatia, Pankaj; Cummis, Cynthia; Draucker, Laura; Rich, David; Lahd, Holly; Brown, Andrea. "Product Standard Greenhouse Gas Protocol" (PDF). Greenhouse Gas Protocol. p. 6. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ↑ Bhatia, Pankaj; Cummis, Cynthia; Draucker, Laura; Rich, David; Lahd, Holly; Brown, Andrea. "Product Standard Greenhouse Gas Protocol". ghgprotocol.org. p. 19. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- 1 2 Bhatia, Pankaj; Cummis, Cynthia; Draucker, Laura; Rich, David; Lahd, Holly; Brown, Andrea. "Product Standard Greenhouse Gas Protocol". ghgprotocol.org. p. 23. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ↑ Bhatia, Pankaj; Cummis, Cynthia; Draucker, Laura; Rich, David; Lahd, Holly; Brown, Andrea. "Product Standard Greenhouse Gas Protocol". ghgprotocol.org. p. 36. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ↑ Gallo, Iciar. "ISO 14067 - What is it and why is it useful for carbon footprint?". advisera.com. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ↑ Meinrenken, Christoph J.; Chen, Daniel; Esparza, Ricardo A.; Iyer, Venkat; Paridis, Sally P.; Prasad, Aruna; Whillas, Erika (10 April 2020). "Carbon emissions embodied in product value chains and the role of Life Cycle Assessment in curbing them". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 6184. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.6184M. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-62030-x. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7148294. PMID 32277082.

- ↑ NICA 2019, pp. 10–17

- ↑ "Protocols & Standards". Carbon Offset Guide. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ↑ "Voluntary Offset Programs". Carbon Offset Guide. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ↑ Kollmus, Anja; Zink, Helge; Polycarp, Clifford (2008). A Comparison of Carbon Offset Standards - Making Sense of the Voluntary Carbon Market (PDF) (Report). WWF Germany. pp. 11–12. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- ↑ SEI-GHGMI 2019, pp. 19–20

- 1 2 SEI-GHGMI 2019, pp. 18–31

- ↑ NICA 2019, pp. 24–29

- ↑ "ISO 14064-2:2006 - Greenhouse gases -- Part 2: Specification with guidance at the project level for quantification, monitoring and reporting of greenhouse gas emission reductions or removal enhancements". www.iso.org. 9 December 2015. Archived from the original on 10 January 2017. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ↑ Greenhouse Gas Protocol Project Accounting 2004, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Greenhouse Gas Protocol Project Accounting 2004, p. 7.

- ↑ "Project Protocol - Greenhouse Gas Protocol". ghgprotocol.org. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ↑ Rich, D.; Bhatia, P.; Finnegan, J.; Levin, K.; Mitra, A. (2014). Greenhouse Gas Protocol - Policy and Action Standard (PDF) (Report). World Resources Institute. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ↑ VCS Standard (PDF) (Report). 4.4. Verra. 2022. p. 4. Retrieved 21 December 2022.

- ↑ "Methodologies". Verra. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ↑ "carbonfootprint.com - Verified Carbon Standard (VCS) - Carbon Offsetting". www.carbonfootprint.com. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

- ↑ "Depth matters for soil carbon accounting – CarbonPlan". carbonplan.org. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- ↑ Michaelowa, Axel; Shishlov, Igor; Hoch, Stephan; Bofill, Patricio; Espelage, Aglaja (2019). Overview and comparison of existing carbon crediting schemes (PDF). Helsinki: Nordic Initiative for Cooperative Approaches (NICA) and Perspectives Climate Group Gmbh. p. 28.

- ↑ Michaelowa, Axel; Shishlov, Igor; Hoch, Stephan; Bofill, Patricio; Espelage, Aglaja (2019). Overview and comparison of existing carbon crediting schemes (PDF). Helsinki: Nordic Initiative for Cooperative Approaches (NICA) and Perspectives Climate Group Gmbh. pp. 25–26.

- ↑ Benchimol, A.; Gillenwater, G.; Broekhoff, D. (2022). Frequently Asked Questions:Green Power Purchasing Claims and Greenhouse Gas Accountng (PDF). Greenhouse Gas Management Institute and Stockholm Environmental Institute. p. 5. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ↑ "Renewable Electricity: How do you know you are using it?" (PDF). National Renewable Energy Lab. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ↑ Camille, Bond. "Renewable Energy Credits Allow Companies to Overstate Emissions Reductions". Scientific American. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ↑ Singh, N.; Damassa, T.; Alarcon-Diaz, S.; Sotos, M. (2014). EXPLORING LINKAGES BETWEEN NATIONAL AND CORPORATE/FACILITY GREENHOUSE GAS INVENTORIES (PDF). World Resources Institute. p. 11. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ↑ US EPA, OAR (23 October 2017). "Plenary of 2017 International Emissions Inventory Conference". www.epa.gov. Presentation by Hong Chiu, Slide 8. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ↑ Darby, Megan (16 September 2019). "Net zero: the story of the target that will shape our future". Climate Home News. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ↑ "Companies taking action". Science Based Targets. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ↑ "Race to Net Zero Campaign". United Nations:Climate Change. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ↑ "The Net-Zero Standard". Science Based Targets. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ↑ "Getting Net Zero Right". Net Zero Climate. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ↑ SBTi Corporate Net-Zero Standard (PDF). 1.0. Science Based Targets Initiative. October 2021. p. 29. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ↑ "CDP" (PDF). Rolls-Royce. Retrieved 17 April 2019.

- ↑ "CDP reports record number of disclosures and unveils new strategy to help further tackle climate and ecological emergency". Retrieved 21 May 2022.

- ↑ CDP Technical Note: Reporting on Transition Plans (PDF). CDP. 2022. p. 6. Retrieved 27 December 2022.

- ↑ LoPucki 2022, pp. 450–452.

- ↑ Curry, Tom; Hellgren, Luke; Russell, Pye; Fraioli, Sierra (2022). Benchmarking Methane and Other GHG Emissions Of Oil & Natural Gas Production in the United States (PDF). Clean Air Task Force.

- ↑ Clifford, Catherine (14 July 2022). "Hilcorp Energy, Exxon Mobil and ConocoPhillips release the most greenhouse gasses among U.S. oil and gas companies". CNBC. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

- ↑ "Carbon emissions report says 100 companies to blame for 71% of greenhouse gases". Wired UK. ISSN 1357-0978. Retrieved 27 May 2023.

- ↑ "Just 100 companies responsible for 71% of global emissions, study says". the Guardian. 10 July 2017. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ↑ "A List companies". www.cdp.net. Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- ↑ Lee, Jessica (7 September 2021). "Only 100 Corporations Responsible For Most of World's Greenhouse Gas Emissions?". Snopes. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ↑ Climate Change Disclosure in G20 Countries-Stocktaking of corporate reporting schemes (PDF). Paris: OECD. 2015. p. 20.

- 1 2 3 4 Bauckloh, Tobias; Klein, Christian; Pioch, Thomas; Schiemann, Frank (29 March 2022). "Under Pressure? The Link Between Mandatory Climate Reporting and Firms' Carbon Performance". Organization & Environment. 36: 126–149. doi:10.1177/10860266221083340. hdl:10419/250748. ISSN 1086-0266.

- ↑ Fung, Archon; O'rourke, Dara (1 February 2000). "Reinventing Environmental Regulation from the Grassroots Up: Explaining and Expanding the Success of the Toxics Release Inventory". Environmental Management. 25 (2): 115–127. doi:10.1007/s002679910009. ISSN 1432-1009. PMID 10594186. S2CID 12073503.

- ↑ Belkhir, Lotfi; Bernard, Sneha; Abdelgadir, Samih (1 January 2017). "Does GRI reporting impact environmental sustainability? A cross-industry analysis of CO2 emissions performance between GRI-reporting and non-reporting companies". Management of Environmental Quality. 28 (2): 138–155. doi:10.1108/MEQ-10-2015-0191. ISSN 1477-7835.

- ↑ Haque, Faizul; Ntim, Collins G (December 2017). "Environmental Policy, Sustainable Development, Governance Mechanisms and Environmental Performance: Environmental Policy, Corporate Governance and Environmental Performance". Business Strategy and the Environment. 27 (3): 415–435. doi:10.1002/bse.2007. S2CID 158331788.

- 1 2 Yang, Lavender; Muller, Nicholas; Liang, Pierre (16 September 2021). "The Real Effects of Mandatory CSR Disclosure on Emissions: Evidence from the Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program". The Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance. Retrieved 30 December 2022.

- ↑ Climate Change Disclosure in G20 Countries-Stocktaking of corporate reporting schemes (PDF). Paris: OECD. 2015. p. 41.

- ↑ LoPucki 2022, pp. 460–462.

- 1 2 Baker, B. (17 September 2020). "Scope 3 Carbon Emissions: Seeing the Full Picture". MSCI. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- 1 2 Fickling, David; He, Elaine (30 September 2020). "The Biggest Polluters Are Hiding in Plain Sight". Bloomberg. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ↑ Busch, Timo; Johnson, Matthew; Pioch, Thomas (February 2022). "Corporate carbon performance data: Quo vadis?". Journal of Industrial Ecology. 26 (1): 350–363. doi:10.1111/jiec.13008. ISSN 1088-1980. S2CID 201478727.

- ↑ Lloyd, Shannon M.; Hadziosmanovic, Maida; Rahimi, Kian; Bhatia, Pankaj (24 June 2022). "Trends Show Companies Are Ready for Scope 3 Reporting with US Climate Disclosure Rule".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Russell, S.; Akopian, Y. (12 March 2019). "Many Companies Inaccurately Estimate the Climate Benefits of Their Products". Greenhouse Gas Protocol. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ↑ Caro, Felipe; Corbett, Charles J.; Tan, Tarkan; Zuidwijk, Rob (12 October 2011). "Carbon-Optimal and Carbon-Neutral Supply Chains". Economics of Innovation eJournal: 5. SSRN 1947343 – via SSRN.

- ↑ Raynaud, J. (November 2015). "Carbon Compass: Investor guide to carbon footprinting – IIGCC". IIGCC. p. 21. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ↑ "CDP Climate Change 2021 Reporting Guidance". guidance.cdp.net. Section C.5.2. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- ↑ Caro, Felipe; Corbett, Charles J.; Tan, Tarkan; Zuidwijk, Rob (12 October 2011). "Carbon-Optimal and Carbon-Neutral Supply Chains". Economics of Innovation eJournal: 7. SSRN 1947343 – via SSRN.

- ↑ US EPA, OAR (25 January 2022). "Double Counting". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- 1 2 SEI 2014, p. 15

- ↑ Kollmuss, Anja; Lazarus, Michael; Schneider, Lambert (17 March 2014). Single-year mitigation targets: Uncharted territory for emissions trading and unit transfers (Report). SEI Working Papers. Working Paper No. 2014-01.

- ↑ "Carbon offsets used by major airlines based on flawed system, warn experts". the Guardian. 4 May 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ↑ Temple, L.; Song, J. "The Climate Solution Actually Adding Millions of Tons of CO2 Into the Atmosphere". ProPublica. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ↑ Astor, Maggie (18 May 2022). "Do Airline Climate Offsets Really Work? Here's the Good News, and the Bad". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ↑ Burkart, K (16 March 2022). "REDD+ ALERT: Are nature-based carbon offsets part of the climate problem? | Greenbiz". GreenBiz. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ↑ Myers, J.E.; Parra, M.A.; Bedford, C. (9 November 2021). "How Carbon Offsetting Can Build a Forest (SSIR)". ssir.org. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- ↑ LLP, Latham & Watkins (9 May 2022). "ISSB Announces Working Group and Forum to Coordinate with Country-Specific ESG Reporting Standards". Environment, Land & Resources. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ↑ Ohl, Andreas; Horn, Heather; Wieman, Valerie (10 October 2022). "Navigating the ESG landscape: Comparison of the "Big Three" Disclosure Proposals". The Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ↑ EDF 2021, p. 4

- ↑ "SBTi launches world-first net-zero corporate standard". Science Based Targets. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ↑ "ISO 14068 - Greenhouse Gas Management and Related Activities". NQA Blog. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ↑ "ISO 14068 - Greenhouse Gas Management and Related Activities". NQA. Retrieved 2 January 2023.

- ↑ CDP Global Supply Chain Report 2021, p. 4

- ↑ Science Based Targets Initiative 2021, p. 8

- ↑ CDP Global Supply Chain Report 2021, p. 13

- ↑ EPA Emerging Trends in Supply Chain Emissions Engagement 2018, pp. 17–18

- ↑ EPA Emerging Trends in Supply Chain Emissions Engagement 2018, pp. 21–22

- 1 2 EDF 2021, p. 3

- ↑ VALUE CHAIN (SCOPE 3) INTERVENTIONS – GREENHOUSE GAS ACCOUNTING & REPORTING GUIDANCE (PDF) (Report) (Version 1.1 ed.). Gold Standard. 2021. p. 7.

- ↑ US EPA, OAR (24 July 2015). "How to Engage Suppliers". www.epa.gov. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- ↑ Belletti, Elena; Schelble, Rachel (8 February 2022). "Voluntary carbon markets: here to stay?". Wood Mackenzie. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ↑ "Carbon credits: Scaling voluntary markets". McKinsey. 29 January 2021. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ↑ EDF 2021, p. 2

- ↑ Magazine, Smithsonian; Morrison, Jim. "A New Generation of Satellites Is Helping Authorities Track Methane Emissions". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ↑ Gurney, Kevin R.; Liang, Jianming; Patarasuk, Risa; Song, Yang; Huang, Jianhua; Roest, Geoffrey (16 October 2020). "The Vulcan Version 3.0 High‐Resolution Fossil Fuel CO 2 Emissions for the United States". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 125 (19): e2020JD032974. Bibcode:2020JGRD..12532974G. doi:10.1029/2020JD032974. ISSN 2169-897X. PMC 7583371. PMID 33133992.

- ↑ Gurney, Kevin Robert; Liang, Jianming; Roest, Geoffrey; Song, Yang; Mueller, Kimberly; Lauvaux, Thomas (2 February 2021). "Under-reporting of greenhouse gas emissions in U.S. cities". Nature Communications. 12 (1): 553. Bibcode:2021NatCo..12..553G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20871-0. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7854656. PMID 33531471.

- ↑ Mueller, K. L.; Lauvaux, T.; Gurney, K. R.; Roest, G.; Ghosh, S.; Gourdji, S. M.; Karion, A.; DeCola, P.; Whetstone, J. (20 July 2021). "An emerging GHG estimation approach can help cities achieve their climate and sustainability goals". Environmental Research Letters. 16 (8): 084003. Bibcode:2021ERL....16h4003M. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ac0f25. ISSN 1748-9326.

- ↑ Roberts, David (16 July 2020). "The entire world's carbon emissions will finally be trackable in real time". Vox. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ↑ Harvey, F. (9 November 2022). "Oil and gas greenhouse emissions 'three times higher' than producers claim". the Guardian. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

Other books, reports and journals cited

- Broekhoff, Derik; Gillenwater, Michael; Colbert-Sangree, Tani; Cage, Patrick (2019). Securing Climate Benefit: A Guide to Using Carbon Offsets (PDF) (Report). Stockholm Environment Institute & Greenhouse Gas Management Institute. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- CDP (2021). Engaging the Chain: Driving Speed and Scale (PDF) (Report). London: CDP Worldwide. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- Kizzier, K.; Hanafi, A.; Ogata, C.; Kellyand, A.; et al. (2021). Trends in the Voluntary Carbon Markets: Where We Are and What's Next (PDF) (Report). Environmental Defense Fund and ENGIE Impact. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- EPA (2018). Emerging Trends in Supply Chain Emissions Engagement (PDF) (Report). Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- Fong, Wee Kean; Sotos, Mary; Doust, Michael; Schultz, Seth; et al. (2021). Global Protocol for Community-Scale Greenhouse Gas Inventories (PDF) (Report). World Resources Institute.

- Green, Jessica (2010). "Private Standards in the Climate Regime: The Greenhouse Gas Protocol" (PDF). Business and Politics. 12 (3): 1–37. doi:10.2202/1469-3569.1318. S2CID 6111404. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- LoPucki, Lynn M. (20 May 2022). "Corporate Greenhouse Gas Disclosures". 56 UC Davis Law Review, No. 1, UCLA School of Law, Public Law Research Paper No. 22-11. SSRN 4051948. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- Michaelowa, Axel; Shishlov, Igor; Hoch, Stephan; Bofill, Patricio; et al. (2019). Overview and Comparison of Existing Carbon Crediting Cchemes (PDF) (Report). Helsinki: Nordic Initiative for Cooperative Approaches (NICA) and Perspectives Climate Group Gmbh. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- Ranganathan, J.; Corbier, L.; Bhatia, P.; Schmitz, S.; et al. (March 2004). GHG Protocol Corporate Accounting and Reporting Standard (PDF) (Report). World Resources Institute. Retrieved 20 December 2022.

- Rich, D.; Bhatia, P.; Finnegan, J.; Levin, K.; Mitra, A. (2004). The GHG Protocol for Project Accounting (PDF) (Report). World Resources Institute. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- Schneider, L.; Kollmuss, A.; Lazarus, M. (2014). Addressing the risk of double counting emission reductions under the UNFCCC (PDF) (Report). SEI. Retrieved 31 December 2022.

- SBTi Criteria and Recommendations (PDF) (Report). 5.0. Science Based Targets Initiative. October 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2023.