Stunning is the process of rendering animals immobile or unconscious, with or without killing the animal, when or immediately prior to slaughtering them for food.

Rationale

Within the European Union, most animals slaughtered for human consumption are killed by cutting major blood vessels in the neck or thorax so that rapid blood loss occurs. After a certain degree of blood loss has occurred, the animal will become unconscious, and after a greater blood loss death will ensue. From the moment of cutting until the loss of consciousness, the animal experiences pain, stress, and fear. Without stunning, the time between cutting through the major blood vessels and insensibility, as deduced from behavioural and brain response, is up to 20 seconds in sheep, up to 25 seconds in pigs, up to 2 minutes in cattle, up to 2.5 or more minutes in poultry, and sometimes 15 minutes or more in fish. If one seeks to minimise animal suffering in slaughter, stunning is necessary. The best stunning method depends on the species; the quality of equipment and the adequate training of personnel also influence effectiveness.[1]

History

A primitive form of stunning was used in premodern times in the case of cattle, which were poleaxed prior to being bled out. However, prior to slaughter pistols and electric stunners, pigs, sheep, and other animals (including cattle) were simply struck while fully conscious.

The belief that it was unnecessarily cruel to slaughter an animal against its will eventually led to the compulsory adoption of stunning methods in many countries. One of the first campaigners on the matter was the eminent physician, Benjamin Ward Richardson, who spent many years of his later working life developing more ‘humane’ methods of slaughter. As early as 1853, he designed a lethal chamber that would gas animals to death supposedly painlessly and without their knowledge, and he founded the Model Abattoir Society in 1882 to investigate and campaign for other methods of slaughter. He even experimented with the use of electric current at the Royal Polytechnic Institution.[2]

The development of stunning technologies occurred largely in the first half of the twentieth century. In 1911, the Council of Justice to Animals (later the Humane Slaughter Association) was created to improve the slaughter of livestock and address the killing of unwanted pets.[3] In the early 1920s, the HSA introduced and demonstrated a mechanical stunner, which led to the adoption of stunning by many local authorities."[4]

The HSA played a key role in the passage of the Slaughter of Animals Act 1933. This made the mechanical stunning of cows and electrical stunning of pigs compulsory, with the exception of Jewish and Muslim meat.[4] Modern methods, such as the captive bolt pistol and electric tongs were required and the Act's wording specifically outlawed the poleaxe. The period was marked by the development of various innovations in slaughterhouse technologies, not all of them particularly long-lasting.

Modern methods

In modern slaughterhouses a variety of stunning methods are used on livestock. Methods include:

- Electrical stunning

- Gas stunning

- Percussive stunning

Electrical stunning

Electrical stunning is done by sending an electric current through the brain and/or heart of the animal before slaughter. Current passing through the brain induces an immediate but non-fatal general convulsion that produces unconsciousness. Current passing through the heart produces an immediate cardiac arrest that also leads shortly to unconsciousness and death. It is a controversial subject however. With chickens for example, over stunning leads to bone fractures and/or electrocution which prevents bleeding of the animal. This negatively affects the quality of the meat, and therefore under stunning is an attractive practice for slaughterhouses.

In the Netherlands, for example, the law states that poultry must be stunned for 4 seconds minimum with an average current of 100 mA, which leads to systematic under stunning.

The CrustaStun is a device designed to administer a lethal electric shock to shellfish (such as lobsters, crabs, and crayfish) before cooking. This avoids boiling a live shellfish which may be able to experience pain in a way similar to vertebrates. The device works by applying a 120 volt 2–5 amp electrical shock to the animal. It is reported the CrustaStun renders the shellfish unconscious in 0.3 seconds and kills the animal in 5 to 10 seconds, compared to 3 minutes to kill a lobster by boiling or 4.5 minutes for a crab.[5]

Gas stunning

With gas stunning animals are exposed to a mixture of breathing gases (argon and nitrogen for example) that produce unconsciousness or death through hypoxia or asphyxia. Carbon dioxide is the main gas used today. The process is not instantaneous, with reported signs of severe distress before respiratory failure when done with carbon dioxide.[6]

Percussive stunning

With percussive stunning, a device which hits the animal on the head, with or without penetration, is employed. Such devices, such as the captive bolt pistol, can be either pneumatic, or powder-actuated. Percussive stunning produces immediate unconsciousness through brain trauma. The process often requires multiple attempts. One study looking at captive bolt guns on cattle found that 12% were shot multiple times, and 12.5% were inadequately stunned.[7]

Gallery

.jpg.webp) Captive bolt pistol

Captive bolt pistol Modern captive bolt device

Modern captive bolt device Stunning a cow with a captive bolt

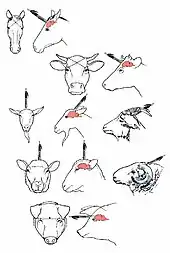

Stunning a cow with a captive bolt Directions for positioning bolt gun to ensure swift stunning

Directions for positioning bolt gun to ensure swift stunning

European regulations

The European Convention for the Protection of Animals for Slaughter, or Slaughter Convention (Council of Europe, 1979), requires all large animals to be stunned before slaughter through one of the three modern methods (concussion, electronarcosis, or gas), and prohibits the use of pole-axes, hammers and puntillas. Parties may permit exemptions for religious slaughter, emergency slaughter, slaughter of poultry, rabbits and other small animals.[8] On the other hand, the European Court of Justice (an EU institution) ruled on 17 December 2020 that member states of the European Union may also require a reversible pre-cut stunning procedure in ritual slaughter in order to promote animal welfare.[9]

United States regulations

Stunning is regulated by the provisions of the Humane Methods of Slaughter Act (7 U.S.C. 1901), which the Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) is mandated to uphold under the Federal Meat Inspection Act (21 U.S.C. 603 (b)). No similar provision exists in the Poultry Products Inspection Act of 1957 (21 U.S.C. 451 et seq.).

After confirmation of the first U.S. BSE case, FSIS issued regulations (69 FR 1887, 12 January 2004) prohibiting the use of the most widely used stunning device (air-injection captive bolt stun gun) because the compressed air device (in contrast to the blank cartridge-driven or non-penetrating captive bolt) has been shown to force pieces of brain and other central nervous system (CNS) tissue into the bloodstream. Cattle blood is processed primarily for use as a protein supplement in animal feeds and milk replacer for calves, and could transmit BSE if it contained specified risk materials (SRMs include brain and CNS tissue).[10]

See also

References

- ↑ Blokhuis, H. (15 June 2004). "Opinion of the Scientific Panel on Animal Health and Welfare on a request from the Commission related to welfare aspects of the main systems of stunning and killing the main commercial species of animals". The EFSA Journal. European Food Safety Authority. 45: 1–29. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2004.45.

- ↑

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Power, D'Arcy (1901). "Richardson, Benjamin Ward". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Power, D'Arcy (1901). "Richardson, Benjamin Ward". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (1st supplement). London: Smith, Elder & Co. - ↑ "Humane Slaughter Association Newsletter March 2011" (PDF). Humane Slaughter Association. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- 1 2 "History of the HSA". Humane Slaughter Association. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- ↑ McSmith, A. (21 November 2009). "I'll have my lobster electrocuted, please". London: The Independent (Newspaper). Archived from the original on 2022-05-25. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ "CO2 shortage a chance to move away from 'cruel, archaic' use of gas to slaughter farm animals, say campaigners". The Independent. 30 June 2018. Archived from the original on 2022-05-25. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ↑ Atkinson, S; Velarde, A; Algers, B (2023-01-01). "Assessment of stun quality at commercial slaughter in cattle shot with captive bolt". Animal Welfare. 22 (4): 473–481. doi:10.7120/09627286.22.4.473. ISSN 0962-7286.

- ↑ "Details of Treaty No.102. European Convention for the Protection of Animals for Slaughter". coe.int. Council of Europe. 10 May 1979. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- ↑ European Court of Justice (17 December 2020). "Judgment in Case C-336/19" (PDF). Press release. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ↑ CRS Report for Congress: Agriculture: A Glossary of Terms, Programs, and Laws, 2005 Edition - Order Code 97-905 Archived 12 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine

External links

- The Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO) outlines practical suggestions for humane handling and slaughter of livestock.