Canadian fashion refers to the styles, trends, design, and production of clothing, footwear, accessories, and other expressions of fashion in Canada and the polities it is descended from.

Since time immemorial, the Indigenous cultures of Canada designed clothing and accessories for practical application in contention with the natural elements, as well as for ritualistic and spiritual purposes. Indigenous-Canadians maintain fashions that are distinct to their particular cultures. Beginning from the 16th century after the founding of Port-Royal, developing factors such as continued European settlement, the North American fur trade, and the establishment of proto-Canadian colonies, such as those of New France and British North America, incrementally introduced western fashions throughout the region, which were often modified or innovated to adapt to local geography.

From the 16th century onward, Canada’s fashion history can be divided into discernable eras that are characterized by prevalent styles particular to the time period. These various modes of dress have often been influenced by the predominant upper-class fashions of western Europe, notably Britain and France, as well as the geographical realities of living in Canada and the rugged lifestyles therein.

Canada’s fashion economy includes numerous clothing and accessory brands (such as Arc'teryx and Lululemon), department stores (such as the historical Hudson’s Bay Company and Holt Renfrew), various annual and semi-annual industry events in Vancouver, Edmonton, Toronto, Ottawa, and Montreal, fashion magazines (such as Elle Canada and Fashion Magazine), and a variety of postsecondary programs in fashion design and marketing.

Early history

New France and the early Fur Trade (1530s to 1750s)

European exploration northwestward, into the frontier of Rupert’s Land, the North-Western Territory, and the Columbia District, was in large part motivated by the North American fur trade, establishing a network of forts and supply routes that laid the developmental groundwork for the modern Canadian state. Indigenous and European hunters and trappers supplied trade networks that capitalized on the demand for beaver pelts in European markets.[1]

Capotes (long wrap-style wool coats, often complete with a hood) were worn by European settlers, traders, trappers, and hunters, as well as Indigenous peoples, since the earliest days of the fur trade. These coats were known to be easy to move in, and were first traded to the Mi’kmaq by French sailors. The Hudson’s Bay Company, which was granted monopoly over Rupert's Land via royal charter from Charles II of England, sold capotes (also called “blanket coats”), fabricated out of the company’s unique “point blanket”, from trading posts such as Moose Factory, New Severn, York Factory, and Fort Churchill as early as the mid-17th century.[2][3]

Beginning in the 17th century, European explorers and traders increasingly wore mukluks; hide boots originally crafted by Inuit peoples using sealskin and caribou skin. Mukluks were designed for maneuverability and warmth, and were blind stitched with sinew thread to make watertight seams, thus being suitable for tundra. European adoption of mukluks in turn influenced Indigenous crafting by introducing new materials, sewing techniques, and styles, as seen in the increased used of tassels and new beading patterns.[4]

Habitants (French-Canadian farmers and fishers) comprised 80% of the population of New France by the time of the British conquest in 1763. Habitant clothing was largely homemade or spun by local weavers, usually using linen, hemp, or wool, and lined with leather or fur, and was similar to the conservative clothing worn in the French countryside. Men tended to wear a shift or shirt, breeches, wool stockings, sometimes a vest or waistcoat, and either leather shoes, clogs or moccasins. Men would also wear breechclouts or toques depending on the season. Daily-wear for women included cotton shifts, woolen skirts over a petticoat, wool stockings held up by garters, bodices, bonnets, and buckle shoes or clogs. Habitant women also kept dresses, mantles, aprons, and shawls.[5]

The bourgeoisie of New France generally wore clothes with comparatively finer fabrics, such as silk and velvet, and utilized a wider variety of colour. Men often wore wigs and tri-corner hats with feathers, decorative buttons, and braids, and tended to have embroideries on their clothing. Bourgeois men also tended to wear ties or scarves made of muslin. Bourgeois women wore decorative fashions, such as blouses with lace collars and skirts with pleats, generally more fitted dresses and dress coats than their lower-class counterparts, and often carried fans or parasols.[5]

New France nobility wore similar fashions to the bourgeoisie, but were generally more lavish and extravagant in their fabrics and designs. Men wore wigs and tri-corner hats, although before the 18th century, these wigs were often so large that hats had to be carried underarm. They wore shirts with lace collars and cuffs, Steinkerque lace cravats, gold and silver-threaded vests and coats, and silk pants, stockings, and shoes. Noblemen also often carried canes, wore gloves, and even as wigs downsized, the tradition of carrying hats underarm persisted.[5]

Noble women wore bonnets decorated with lace and gems (often in the shape of butterflies), as well as blouses adorned with frilled lace and with funnel-shaped lace sleeves. Their dresses and skirts often had gold and silver thread, floral designs, fringes, and were typically layered over petticoats. Dress trains in New France were also traditionally cut to length in accordance with one’s level of nobility. Like their male counterparts, noble women wore silk stockings and shoes. Accessories included parasols, gloves, and gold and silver ribbons that often held garments together.[5]

Post-New France and the new British colonies (1760s to 1800s)

Though the early years following the British conquest of New France did not see a dramatic shift in the way of working-class fashion, the changing styles among the upper-classes in England and France did influence those of the Canadian colonies. Fashions of upper-class Canadian women reflected those of their European counterparts, such as through the use of lace, boned stays, pastels, and ruffles. Though English styles were incorporated into the wardrobes of French-Canadian women, these styles were more prevalent in English-majority areas during this period, particularly in Upper Canada and the Atlantic colonies, where immigrants from Britain and the influx of United Empire Loyalists tended to settle. English and French styles during this time were typically distinguished by their level of extravagance; English-Canadian dresses tended to be more toned-down and conservative.[6]

In contrast to the macaroni fashion that took off in London during the Georgian era, men’s fashion in the Canadian colonies tended to shift toward a comparatively casual and sleek appearance. Men’s clothes in the latter part of the 18th century became tighter over time, and three-piece suits started to become more commonplace. [6]

Regency Era (1810s to 1830s)

The Regency era marks the beginning of the Great Migration of Canada, in which roughly 800,000 migrants, largely from the British Isles, moved to British North America. As a result, London upper-class fashions, such as those of the Romantic movement and the dandy trend, became much more predominant throughout the Canadian colonies; in Upper Canada, the Maritimes, and even in Lower Canada, where a Francophone majority persisted. In Fashion: A Canadian Perspective, Alexandra Palmer explains that “by the 1830s Lower Canadian professionals were spending a greater proportion of their income (some 20%) on attire. This was more than any other class, making them leaders in fashion as well as politics. They were, for example, early purchasers not only of trousers but also the stylish Wellington and Brunswick boots advertised in Lower Canadian newspapers after 1815. […] These men went from wearing wigs or tying back their own long hair […] to short natural styles.”

"Dandy" fashion entailed some common elements: dark colours, blue tailcoats with gold buttons, white muslin shirts, trousers replacing breeches, fabrics like silk, wool, cotton, and buckskin, and generally tight-fitting clothes. Other important articles and accessories for upper-class men included black silk tophats (or “toppers”), cravats, gloves, canes, pocket watches, monocles, and greatcoats.[7]

_tartan.png.webp)

Women’s high fashion took a dramatic shift from the understated fashions of decades prior as extravagant styles became popular, utilizing such elements as poofy sleeves, bell-shaped skirts, elaborate hats, and ribbons. Empire dresses from the early part of the century were high-waisted with a fitted bodice, and were flowing and loose fitting at the bottom. Preceding years over the course of this period saw older styles blending into new, such as dresses with “empire” waistlines but with fuller skirts, and also saw the beginnings of gigot-style sleeves as a trend. As sleeves expanded during the 1820s, the common fashion for waistlines also inched lower overtime.[8]

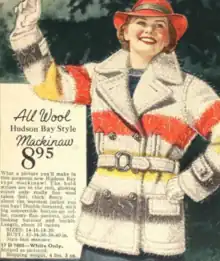

During the War of 1812, the mackinaw jacket was invented out of necessity. During the occupation of Fort Mackinac, the British commander Charles Roberts requisitioned a supply of Hudson’s Bay point blankets from the British Indian Department to manufacture greatcoats for the coming winter. Due to the shortage of blue fabric needed to complete the order, the balance was supplemented by blankets with a black-on-red tartan pattern. After being advised by a dispatch runner on the impracticality of travelling in long greatcoats between Montreal and Mackinaw during winter due to snowdrifts, it was recommended that they instead fabricate shorter double-breasted jackets, thus inventing what became known as the ‘’mackinaw jacket’’.[9][10]

Confederation Era (1840s to 1890s)

Everyday fashion for women during the Confederation era was characterized by variety, ornamentation, and ever-changing styles. Dresses in the 1830s were notable for their width, voluminousness, and gigot-style sleeves. The 1850s saw the popularity of crinolines skirts and bell-shaped shirts. Over time, the fashionability of the perch at the back of the dress shifted to smoother lines, akin to an “hour-glass” shape by the end of the 19th century. Canadian middle-class women often had to modify their existing attire to sustain the changing trends.[11]

Formal dress for Canadian women was important during this era due to the popularity of costumed theatre, skating carnivals, and balls. Historical figures, such as Marie Antoinette, were popular costume inspirations, and great care was taken to achieve historical accuracy whilst keeping in line with contemporary fashion. The 1870s, for example, saw the popularity of the “princess-style dress”, which was sewn without a waistline and incorporated a white wig and regal velvet sleeve detail. These events were typically themed to celebrate Canadian history or the British Empire, and had a function of disseminating educational themes of technological progress, art, and literature through local newspapers.[12]

Women’s outerwear had to adapt to the changing styles of dress. For example, with the 1850s crinoline trend, overcoats were exchanged for shawls. The paisley shawl, which were already in common use in Scotland and the British Raj, was particularly popular during this time. Hats and bonnets also became particularly popular in the 1880s and 90s, and millinery became a growing trade for women, separate from dressmaking. Materials such as ribbons, lace, flowers, feathers, and sometimes bird ornaments were artistically incorporated as hats came to be seen as increasingly stylish and not simply functional attire.[13]

Professional attire became increasingly prominent with Canada’s burgeoning middle class. These clothes were required to be low-maintenance and perceived as respectable, as masculine fashions gradually shifted from the decorative styles of previous eras in favour of black suits. Though custom-made suits were worn by wealthy and prominent professionals, cheaper ready-made suits became more widely available and marketed through mail-order catalogues by companies like T. Eaton Co. and Dupuis Frères.[14] Fur coats were common during the winter months, as seen in the distinctive designs of R.J. Devlin, who made beaver-fur greatcoats that were known to be particularly popular among members of the Ontario Legislative Assembly.[15]

Increasing simplicity in men’s everyday wear provided the opportunity for personal flare through luxury ornaments and accessories. Such items included pocket watches, detachable collars, ties, cravats, stocks, and tophats.[16]

Other men’s fashions came in the form of leisure and club wear. Sporting attire was produced to meet demand from the increasing interest in activities like hockey, equestrian, cycling, walking, and swimming. For example, breeches became more vogue due to the popularity of horseback riding and cycling.[17] The rise in membership of fraternal organizations, such as the Freemasons and the Orange Order, saw an increased use of ceremonial garments. Such garments included the Freemasons’ apron, based on the functional attire of medieval stonemasons and adorned with Masonic symbols, ribbons, and rosettes, and the collar of the Orange Order in Canada, which was embroidered with British-Canadian symbols like the thistle, shamrock, rose, and maple leaf.[18]

The mid-19th century saw the development of local, custom-made clothing industries and the increase in prestige of fashion design as a trade. Canadian fashion designers during this period were dressmakers and tailors who often ran local storefronts, which may have also sold fabrics and accessories, catering to local urban markets such as Toronto, Montreal, and Ottawa. These businesses often operated under the name of the owner-designer, and by the late 19th to early 20th century, city directories listed an outstanding quantity of local tailors and dressmaking shops. This period also saw labels become a common industry practice for designers to guarantee their authorship, and department stores began selling designer clothing alongside ready-made selections. Famous elite Canadian designers during this period include G.M. Holbrook (Ottawa), William Stitt and Co. and O’Brien (Toronto), and J.J. Miloy (Montreal), who were notably patronized by the governor general Frederick Arthur Stanley, 16th Earl of Derby and his wife, Lady Stanley.[19]

Edwardian Era, World War 1, and Interwar Period (1900s to 1930s)

.jpg.webp)

Edwardian women’s fashion was characterized notably by the preeminence of Parisian haute couture, which had a marked influence on western fashion broadly, including in the Dominion of Canada. For example, the S-shaped "columnar silhouette", made popular by Parisian couturiers, saw the phasing out of corsets which were fundamental to the fashions of the previous era.[20] Mass-produced clothing also started to become more prevalent, which squeezed the local custom garment industry, particularly in men’s wear. Notable Canadian designers during the 1920s and 30s include Madame Martha, who designed and sold couture clothing in Toronto, and Ida Desmarais, who designed gowns for a Montreal clientele. Gaby Bernier and Marie-Paule Nolin were also important Montreal designers who established their practices during the 1930s. The influx of imports from European designers, particularly those of Paris, to Canadian department stores like Eaton's, Simpson’s, and Holt Renfrew presented further challenges for local producers, although some Canadian designers had garnered enough brand recognition to maintain a presence with department stores, such as Madame Martha's “French Salon” at the Simpson's Toronto location, and Marie-Paule Nolin's in-store salon and couture workroom at Holt Renfrew's Montreal location.[21]

The Edwardian era saw the brightly-coloured military regalia, typical of the previous century, replaced with the Canadian-patterned service dress jacket, which was intended to double as both a field and dress jacket. This jacket was characterized by a stand-up collar secured by hooks and eyes, a 5 to 7-button front closure, two box-pleated breast-pockets with scalloped flaps and buttons, two hip-pockets with flaps, gauntlet-style cuffs, and sometimes coloured shoulder straps. During the First World War, an economy version of this service jacket was introduced in the form of the “Kitchener Pattern”, which notably replaced box-pleats at the breast-pockets with standard pockets.[22]

Efforts toward women’s rights by suffragettes, particularly Canada’s Famous Five, as well as an increase in women’s participation in sport, helped to advance changing ideals for the woman’s role in Canadian society, which was reflected through developments in fashion. Canadian women’s fashion in the 1920s continued a shift away from the more physically restrictive styles of the Confederation era and toward generally more comfortable garments, such as trousers and short skirts. Similar to the developing fashion scenes of other western countries, the flapper style became popular among Canadian women during this decade. As the decade developed, particular styles of women’s articles gained popularity in this vein, such as shift dresses, straight bodices, collars, and all-in-one lingerie, and the corset became increasingly substituted by chemise dresses or camisoles and bloomers.[23]

The 1920’s also saw developments in the way of men’s suits. Similar to women’s fashions of the time, everyday suit-wear became less formal and more considerate of personal comfort. Shorter suit jackets replaced formal long suit jackets for casual wear. The service uniforms of the First World War influenced men’s jackets of the early 1920s; they tended to be high-waisted with narrow lapels. Trousers during this part of the decade also tended to be narrow. The latter half of the decade saw the typical suit jacket develop a lower waistline, wider lapels, and Oxford bags became more popular in place of narrower pants. Men’s headwear during this time was typically stratified by class; upper-class men tended to wear tophats or homburg hats, the middle-class tended to wear fedoras, bowler hats, or trilby hats, while working-class men tended to wear newsboy caps or flat caps.[24]

World War 2 and Post-war Era (1940s to 1950s)

The Second World War temporarily, but drastically, altered the Canadian public’s relationship with fashion. Textiles and metals that were typically used in the production of clothing were often redirected from consumer fashion and toward the war effort. More functional and practical clothing was culturally encouraged and regulated, as the national consciousness focused on a collective effort toward liberating Europe. Feminine fashion, in particular, reflected working class roles as women took up occupations traditionally filled by men, and was even described as an expression of patriotism. In the 1941 Chatelaine feature titled “How Do We Dress From Here?”, Carolyn Damon wrote that “today we think more seriously, and so we dress more seriously.”[25]

As part of the War Measures Act, the Wartime Prices and Trade Board became responsible for the control of goods and services, which affected the country’s fashion economy dramatically. The WPTB’s mandate included supply allocation, manufacturing capacity, labour allotment, product design, product change regulations, distribution of goods and services, and price controls. Because the manufacturing capacity and fabrics of certain clothing articles, such as jackets and pants, directly contradicted the production of military clothing, a simplification program for consumer fashion was enforced, which had the effect of reducing the diversity of available styles, silhouettes, colours, and dimensions. Despite these restrictions, the perpetuation of fashion nonetheless persisted. Newspapers, newsmagazines, and magazines consistently published columns, stories, and features dedicated to opinions and developments in fashion. New clothing designs, accessory descriptions, and stories addressing WPTB restrictions were continuously published throughout the war.[26]

Women’s fashion and fashion journalism continued to develop during the war, as demonstrated through seasonal style changes and the adoption of new clothing articles. For example, the summer fashions of 1940 were described as “gracefully feminine”, while the following autumn shifted to a comparatively narrower silhouette, and the spring of 1941 was distinguished by reduced shoulder padding and shorter and narrower skirts. Women’s suits (typically consisting of a jacket and skirt), in particular, became an important fashion story, turning into a common wardrobe staple and being described as a “Canadian tradition”. In the spring of 1942, the popularity of suits even overtook that of coats and dresses. Similarly, the increased appropriation of slacks by women, a typically male garment at the time, was a major wartime story that represented a shift in gender roles. Manufacturers often developed uniforms for their workforce, which tended to include comfortable low heels, short-sleeved blouses, slacks, and a bandana or snood.[27]

Department store catalogues, such as those of Eaton’s, Simpson's, and Dupuis Frères, continued to have an important influence on women’s fashion in the years following the end of the war. Although rural women in particular mostly used catalogues to order fabrics (from which they would fabricate their own clothing based on designs found in the catalogues), ready-to-wear fashions grew more prevalent as these catalogues became increasingly important to Canadian consumer culture.[28]

Dresses in the 1940s and 50s post-war era shifted away from the pre-war styles of the 1920s and 30s, which emphasized a natural look with shortened skirts, shorter sleeves, lower necklines, and relatively loose-fitting dresses with a somewhat square shape. Post-war dresses tended to fit tighter at the top, while wide and full at the bottom. Corsets, crinolines, and girdles returned to fashion during this period, as the emphasis on slimness increased via the influence of commercial advertising. Catalogues also promoted youth as the standard of feminine beauty, advertising products like creams, hair treatments, complexion pills, and clothes which lent themselves to a more youthful appearance (such as corsets and girdles). Modeling displayed in catalogues distributed between western and eastern Canada had notable differences, as these strict standards for youth and beauty were emphasised more in eastern markets; catalogues issued in western Canada tended to be more liberal in using female models with fuller figures or more aged appearances.[29]

This period was an important time in the development of Canada's department store landscape. With the imminent closing of the North American fur trade, the Hudson's Bay Company underwent a “modernization program” which involved entering the commercial retail space. Although the company had operated urban storefronts since the late 19th century, and had established department stores in western Canadian cities such as Vancouver, Victoria, Winnipeg, Saskatoon, Calgary, and Edmonton since the early 20th century, it wasn’t until the company acquired Morgan’s in 1960 that it entered the larger markets in central Canada. This would begin a monopolising trend within Canada’s developing retail landscape, as the company would go on to acquire Freimans in 1972, Simpson’s in 1978, and Woodward’s in 1993.[30] [31]

Holt Renfrew also made important moves during the post-war era by closing key deals with leading haute couture fashion houses from France and Italy (notably the House of Christian Dior, which Holt Renfrew became the exclusive Canadian distributor for). The company expanded its sales operations in Edmonton, Calgary, and London during the early 1950s, and established key outlets at some of Canada’s grand railway hotels, such as the Royal York, Chateau Frontenac, and Château Laurier.[32] [33]

By 1958, most women’s clothing sold in Canada was manufactured domestically, with skilled workers able to produce up to 15 dresses a day on average, although both the textiles and designs were often imported. For example, the “Parisian chemise”, which was introduced to European markets two years prior, was first sold in Canadian stores during this year.[34]

In 1954, the Association of Canadian Couturiers was founded, which was mandated with establishing a recognisable identity and media presence for Canadian design in the broader international market. Renowned members included Montreal's Jacques de Montjoye and Toronto's Frederica. After producing the first all-Canadian fashion show in New York during their inaugural year, the Association continued to produce shows in Canadian cities twice a year, until they disbanded in 1968.[35]

Late 20th Century (1960s to 1990s)

In 1974, the Fashion Designers Association of Canada was founded, which was mandated to promote Canadian designers as well as generate appreciation for the fashion industry's contribution to Canadian society as a whole. This Association was partly founded by Michel Robichaud and Marielle Fleury, who became globally renown when their designs toured Europe in the lead-up to Expo 67. Other notable members included Montreal's Léo Chevalier and John Warden, and Toronto's Pat McDonagh, Claire Haddad, Marilyn Brooks, and Elen Henderson. The Association held seasonal fashion shows in both Toronto and Montreal until 1980, when it disbanded.[36]

Despite the dissolution of two fashion design associations in the 60s and 80s, the developing export market in the final decades of the 20th century marked an increase in global recognition of Canadian fashion design. Canadian fashion designers that garnered significant international reputations during this era include Alfred Sung (co-founder of Club Monaco), Jean-Claude Poitras, Simon Chang, Hilary Radley, Linda Lundstrom, and Wayne Clark.[37] Furthermore, Canada's third and current fashion design association, the Fashion Design Council of Canada, was founded at the end of the millennium, operating as "the national trade association representing the interests of the Canadian fashion design industry."[38][39]

The late 20th century constitutes an era in which many of Canada's most prolific brands were founded. This includes Ontario brands such as Sorel (1962), Roots (1973), and Moores (1980); Quebec brands such as Aldo (1972), Ardene (1982), and Boutique La Vie en Rose (1984); and British Columbia brands such as Aritzia (1984), Arc'teryx (1989), and Lululemon (1998).

Economy, media, and education

Economy

As of 2023, the Canadian fashion industry is estimated to have generated a revenue of US$17.85bn, and revenue is expected to show an annual growth rate of 12.47% until 2027, resulting in a projected market volume of US$28.56bn.[40]

Canadian brands include Arc'teryx, Canada Goose, Frank and Oak, Herschel Supply Co., Hilary MacMillan, Hudson North, Kit and Ace, Kotn, Lesley Hampton, Mackage, Mejuri, Naked and Famous, Oak + Fort, Rudsak, Smash + Tess, Soia & Kyo, Sorel, and Tentree. Many Canadian clothing store chains also distribute their own original brands, such as Ardene, Aritzia, ALDO, Bluenotes, Boutique La Vie en Rose, Club Monaco, Garage, Harry Rosen, Le Château, Lululemon, Moores, Reitmans, Roots Canada, Tip Top Tailors, and Urban Behaviour.

Media

Fashion magazines published in Canada include Canadian Living, Chatelaine, Dolce, Elle Canada, fab, Fashion Magazine, Flare, glow, Hello! Canada, LOU LOU, NUVO, SHARP, and Vancouver Magazine.

Industry events in Canada include Toronto Fashion Week, Ottawa Fashion Week, Montreal Fashion and Design Festival, Vancouver Fashion Week, and Western Canada Fashion Week, among others.

Some popular Canadian fashion models include Shalom Harlow, Jessica Stam, Yasmin Warsame, Stacey McKenzie, Coco Rocha, Heather Marks, Andi Muise, and Linda Evangelista.[41]

Education

Canadian schools with post-secondary programs in fashion design and marking include Ryerson University School of Fashion, George Brown College, LaSalle College, Wilson School of Design at Kwantlen Polytechnic University, Seneca College, Richard Robinson Fashion Design Academy, Fanshawe College, Humber College, University of Alberta, and School of Media, Art, & Design at St. Clair College.

Museums in Canada dedicated to fashion and textiles, or that maintain significant collections dedicated to fashion history, include the Patricia Harris Gallery of Textiles & Costume at the Royal Ontario Museum, McCord Stewart Museum, the Textile Museum of Canada, the Bata Shoe Museum, the Costume Museum of Canada, and the Mississippi Valley Textile Museum in Almonte, Ontario.[42]

Trends and national costumes

.jpg.webp)

Canadian consumer fashion trends are linked to the legacy of the country’s fashion history and are often an expression of the varied lifestyles associated with Canada’s social classes and geography, as seen in athleisure and functional apparel. The “blanket jacket”, for example, is possibly Canada’s first athleisure garment, and is a continuation of the capotes and mackinaw jackets fashioned from wool blankets. According to Fashion: A Canadian Perspective, “the blanket coat was often labeled in the press as a national costume that represented the Canadian identity.” Modern Canadian brands, like Aritzia and Simons, have drawn inspiration from this model for their own products. Athleisure has had continued influence on Canadian fashion developments, as seen in the innovations in leggings and sweatsuits during the late 20th century by Lululemon and Roots respectively.[43]

The parka is another traditional form of functional fashion, which originates from Indigenous cultures of Northern Canada, and has been adapted and marketed for upscale urban wear by brands such as Quartz Co. and Canada Goose.[44]

Since the mid-20th century, Canada has been a hub for innovation and design in winter boots, with local companies having integrated insulated footwear and convenient street styles. Examples include “cougar pillow” boots, First Nations-inspired moccasin footwear, and the waterproof cold-weather boots designed by Sorel.[45]

Various headwear have been developed in Canada and have often carried cultural and historical significance. Beaver hats and their demand in the European market, for example, were an important driver of the Canadian fur trade. The Calgary white hat is a more contemporary example; a garment of symbolic importance for the city of Calgary, Alberta, rooted in the traditional ranching and farming culture of the area. The "White Hat" provides Calgary with a sense of communal identity, an idealized citizen epitomized in the “Canadian cowboy”, and a sense of living on the margins and distinction from perceived centralising powers within Canada.[46] Although the knitted cap, or "beanie", was not invented in Canada, it has none the less been distinguished within the Canadian consciousness as an important piece of national apparel. Other headgear that were developed in Canada include the tilley hat, the Pangnirtung (or "Pang") hat, and the "Christy stiff" variety of derby hat.[47]

Equestrian style elements have had a marked influence on modern Canadian design and trends. With the enduring popularity of the “horse girl” aesthetic through clothing articles such as women's tailored blazers, tall leather boots, crewneck sweaters, plaid barn jackets, and sleek leggings, this style has been a source of guidance for major brands like Smythe, Aldo, Roots, and Brunette the Label.[48] Smythe’s notoriety as a high-end designer of equestrian-inspired fashion was increased after their blazers were worn by the Duchess of Cambridge at several public events, including the 2011 and 2016 royal tours of Canada. Brands like Street and Saddle and Ellie Mae have adapted recreational equestrian styles for everyday and professional wear, particularly the autumn fashion season.[49][50]

Uniforms

Public service

One of Canada’s most recognizable and internationally-renown uniforms is the ceremonial outfit of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. This uniform consists of the Red Serge (a scarlet military-pattern tunic, complete with a high-neck black collar), midnight-blue breeches with yellow trouser piping, an oxblood Sam Browne belt with white sidearm lanyard and matching oxblood riding boots, brown felt campaign hat (also known as the “stetson hat”), and oxblood gloves.[51]

The fur wedge cap is a traditional piece of headgear for some Canadian police forces, such as the RCMP and Toronto Police Service, as well as the Canadian Armed Forces, where it was in use from the 1890s to the 1970s. It continues to be worn by officer cadets of the Royal Military College of Canada. The outside layer of the cap is usually made from either synthetic fur or an animal product, such as Persian lamb wool, and is designed to fold flat when not in use.[52][53]

Non-governmental organisations

There are a number of Canadian youth associations which require standard-issue uniforms for their members. One such organisation is the Girl Guides of Canada, which has had a myriad of different uniforms for each of its branches since its inception in 1909. The earliest known uniform for Guides included a navy-blue skirt, a red biretta or straw hat (for Summer), navy-blue stockings, white lanyard, and a jersey and neckerchief in "company colours." Currently, youth branches all maintain some variation of a navy-blue shirt or tunic with a trefoil, with optional sashes and scarves.[54]

References

- ↑ Jennifer S.H. Brown. "Beaver Pelts". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ↑ "Hudson's Bay Point Blanket Coat". HBC Heritage. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ↑ "Capots (Art. III. Capots, with some Side Lights on Chiefs' Coats & Blankets, 1774-1821, by A. Gottfred.)". Northwest Journal Online. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ↑ René R. Gadacz (20 October 2015). "Mukluk". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

- 1 2 3 4 Cadeau, C. "Fashion in New France (1700-1750)". All About Canadian History. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- 1 2 Cadeau, C. "Women's Fashion After the Fall of New France (1760s to 1780s)". All About Canadian History. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ↑ Cadeau, C. "Men's Fashion During the Regency Era (1810s to 1830s)". All About Canadian History. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ↑ Cadeau, C. "Women's Fashion During the Regency Era (1810s to 1830s)". All About Canadian History. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ↑ Wooley, H. J. L. (1911). The Sword of Old St. Joe. Chp V, pg 17-21.

- ↑ Cutler, Charles L. (2002). Tracks that speak. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 25-26. ISBN 0618065105.

- ↑ "Everyday Clothing". Canadian Museum of History. Retrieved 2023-02-13.

- ↑ "Fancy Dress". Canadian Museum of History. Retrieved 2023-02-13.

- ↑ "Outerwear and Accessories". Canadian Museum of History. Retrieved 2023-02-13.

- ↑ "Professional Attire". Canadian Museum of History. Retrieved 2023-02-24.

- ↑ "Accessories and Outerwear". Canadian Museum of History. Retrieved 2023-02-24.

- ↑ "Accessories and Outerwear". Canadian Museum of History. Retrieved 2023-02-24.

- ↑ "Leisure and Sports Clothing". Canadian Museum of History. Retrieved 2023-02-24.

- ↑ "Club Wear". Canadian Museum of History. Retrieved 2023-02-24.

- ↑ Cynthia Cooper. "Fashion Design in Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ↑ "Edwardian fashion: A 5-minute Guide". 5 Minute History. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ↑ Cynthia Cooper. "Fashion Design in Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ↑ "Uniforms". Canadian Soldiers. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ↑ Fatima Fyaaz. "Women and Fashion". The Roaring Twenties History Project. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ↑ Fatima Fyaaz. "Women and Fashion". The Roaring Twenties History Project. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ↑ Caton, Susan Turnbull (2004). "Fashion and War in Canada, 1939-1945". In Palmer, Alexandra (ed.). Fashion: A Canadian Perspective. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-8809-0.

- ↑ Caton, Susan Turnbull (2004). "Fashion and War in Canada, 1939-1945". In Palmer, Alexandra (ed.). Fashion: A Canadian Perspective. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-8809-0.

- ↑ Caton, Susan Turnbull (2004). "Fashion and War in Canada, 1939-1945". In Palmer, Alexandra (ed.). Fashion: A Canadian Perspective. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-8809-0.

- ↑ Shirley Lavertu. "Catalogues and Women's Fashion". Canadian Museum of History. Retrieved 2023-03-12.

- ↑ Shirley Lavertu. "Catalogues and Women's Fashion". Canadian Museum of History. Retrieved 2023-03-12.

- ↑ "A chronology of key events in the history of the Hudson's Bay Company". The Canadian Press. Retrieved 2023-03-18.

- ↑ "History of HBC". HBC Heritage. Retrieved 2023-03-18.

- ↑ Alexandra Palmer (1 November 2001). Couture and commerce – the transatlantic fashion trade in the 1950s. UBC Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0774808262.

- ↑ "Holt Renfrew and Co. Ltd". Canadian Register of Commerce & Industry. University of Western Ontario. Archived from the original on 2007-12-03. Retrieved 2023-03-18.

- ↑ "Fashion, food and nuclear fear in the 1950s". CBC Archives. Retrieved 2023-03-13.

- ↑ "Fashion Design in Canada". Cynthia Cooper. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2023-11-12.

- ↑ "Fashion Design in Canada". Cynthia Cooper. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2023-11-12.

- ↑ "Fashion Design in Canada". Cynthia Cooper. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2023-11-12.

- ↑ "Fashion Design in Canada". Cynthia Cooper. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2023-11-12.

- ↑ "Fashion Design Council of Canada / Robin Kay, President". Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada. Retrieved 2023-11-12.

- ↑ "Fashion - Canada". Statista. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ↑ Riaeleza. "8 Most Popular Canadian Fashion Models". Icy Canada. Retrieved 2023-02-24.

- ↑ "Canada". Fashion & Textile Museums. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- ↑ Kristy Archibald. "6 Fashion Trends That Were Born in Canada". Nuvo Magazine. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ↑ Kristy Archibald. "6 Fashion Trends That Were Born in Canada". Nuvo Magazine. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ↑ Kristy Archibald. "6 Fashion Trends That Were Born in Canada". Nuvo Magazine. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ↑ Jeremy Klaszus (4 January 2016). "The White Hat: A Calgary symbol we love to hate". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

- ↑ "Tuque". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2023-03-17.

- ↑ Aleesha Harris. "Equestrian style: The enduring allure of the 'horse girl' esthetic". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 2023-03-05.

- ↑ Aleesha Harris. "Style Q&A: A brand for the 'horse girl in all of us'". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 2023-03-05.

- ↑ Aleesha Harris. "Fall fashion: 10 top trends to shop from Canadian brands". Vancouver Sun. Retrieved 2023-03-05.

- ↑ "Uniform Regulations for the RCMP". RCMPolice.ca (unofficial blog). Retrieved 2023-03-14.

- ↑ Boulton, James J. (2000). Head-dress of the Canadian Mounted Police, 1873–2000. Calgary: Bunker to Bunker Pub. pp. 89–96. ISBN 1894255070.

- ↑ e-Veritas, July 24, 2016, Headdress of the Royal Military College of Canada: A brief history by 8057 Ross McKenzie, former Curator RMC Museum Archived 2016-08-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Canadian Guiding Uniform History". GIRL GUIDE HISTORY TIDBITS. Retrieved 2024-01-04.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)