Caithness | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates: 58°25′N 3°30′W / 58.417°N 3.500°W | |

| Sovereign state | |

| Country | |

| Council area | Highland |

| County town | Wick |

| Area | |

| • Total | 618 sq mi (1,601 km2) |

| Ranked 14th of 34 | |

| Demonym | Caithnesian |

| Chapman code | CAI |

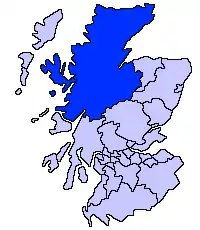

Caithness (Scottish Gaelic: Gallaibh [ˈkal̪ˠɪv]; Scots: Caitnes;[1] Old Norse: Katanes[2]) is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area of Scotland.

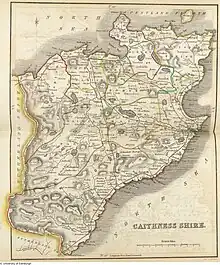

Caithness has a land boundary with the historic county of Sutherland to the west and is otherwise bounded by sea. The land boundary follows a watershed and is crossed by two roads (the A9 and the A836) and by one railway (the Far North Line). Across the Pentland Firth, ferries link Caithness with Orkney, and Caithness also has an airport at Wick. The Pentland Firth island of Stroma is within Caithness.

The name was also used for the earldom of Caithness (c. 1334 onwards) and for the Caithness constituency of the Parliament of the United Kingdom (1708 to 1918). Boundaries are not identical in all contexts, but the Caithness area as of 2019 lies entirely within the Highland council area. Until its demise in the 19th century, the Norn language was the common language of everyday communication for people in Caithness, before being gradually overtaken by Scots (and later, English).[3]

Toponymy

The Caith element of the name Caithness comes from the name of a Pictish tribe known as the Cat or Catt people, or Catti (see Kingdom of Cat). The -ness element comes from Old Norse and means "headland". The Norse called the area Katanes ("headland of the Catt people"), and over time this became Caithness.[2]

The Gaelic name for Caithness, Gallaibh, means "among the strangers", referring to the Norse. The name of the Catti survives in the Gaelic name for eastern Sutherland, Cataibh,[2] and in the old Gaelic name for Shetland, Innse Chat.

Geography

Caithness extends about 30 miles (48 km) north-south and about 30 miles (48 km) east-west, with a roughly triangular-shaped area of about 712 sq mi (1,840 km2). The topography is generally flat, in contrast to the majority of the remainder of the North of Scotland. Until the latter part of the 20th century when large areas were planted in conifers, this level profile was rendered still more striking by the almost total absence of woodland.

It is a land of open, rolling farmland, moorland and scattered settlements. The county is fringed to the north and east by dramatic coastal scenery and is home to large, internationally important colonies of seabirds. The surrounding waters of the Pentland Firth and the North Sea hold a great diversity of marine life. Notable features of the north coast are Sandside Bay, Thurso Bay and Dunnet Bay, Dunnet Head (the northernmost point of Britain) and Duncansby Head (the north-east tip of Britain); along the east coast can be found Freswick Bay, Sinclairs Bay and Wick Bay. To the north in Pentland Firth lies Stroma, the only major island of the county. Away from the coast, the landscape is dominated by open moorland and blanket bog known as the Flow Country which is the largest expanse of blanket bog in Europe, extending into Sutherland. This is divided up along the straths (river valleys) by more fertile farm and croft land. In the far south the landscape is slightly hillier, culminating in Morven, the highest peak in the county at 706 m (2,316 ft).

The county contains a number of lochs, though these are smaller in comparison with the rest of northern Scotland. The most prominent are Loch Heilen, Loch of Wester, Loch Scarmclate, Loch Watten, Loch of Toftingall, Loch Stemster, Loch Hempriggs, Loch of Yarrows, Loch Sand, Loch Rangag, Loch Ruard, Loch an Thulachan, Loch More, Loch Caluim, Loch Tuim Ghlais, Loch Scye, Loch Shurrery, Loch Calder and Loch Mey.

The underlying geology of most of Caithness is Old Red Sandstone to an estimated depth of over 4,000 metres (13,000 ft). This consists of the cemented sediments of Lake Orcadie, which is believed to have stretched from Shetland to Grampian during the Devonian period, about 370 million years ago. Fossilised fish and plant remains are found between the layers of sediment. Older metamorphic rock is apparent in the Scaraben and Ord area, in the relatively high southwest area of the county. Caithness's highest point (Morven) is in this area.

Because of the ease with which the sandstone splits to form large flat slabs (flagstone) it is an especially useful building material, and has been used as such since Neolithic times.

Natural heritage

Caithness is one of the Watsonian vice-counties, subdivisions of Britain and Ireland which are used largely for the purposes of biological recording and other scientific data-gathering. The vice-counties were introduced by Hewett Cottrell Watson, who first used them in the third volume of his Cybele Britannica, published in 1852. He refined the system somewhat in later volumes, but the vice-counties remain unaffected by subsequent local government re-organisations, allowing more accurate comparisons of historical and modern data. They provide a stable basis for recording using similarly sized units, and, although grid-based reporting has grown in popularity, they remain a standard in the vast majority of ecological surveys, allowing data collected over long periods of time to be compared easily.

The underlying geology, harsh climate, and long history of human occupation have shaped the natural heritage of Caithness. Today a diverse landscape incorporates both common and rare habitats and species, and Caithness provides a stronghold for many once common breeding species that have undergone serious declines elsewhere, such as waders, water voles, and flocks of overwintering birds.

Many rare mammals, birds, and fish have been sighted or caught in and around Caithness waters. Harbour porpoises, dolphins (including Risso's, bottle-nosed, common, Atlantic white-sided, and white-beaked dolphins), and minke and long-finned pilot whales[4] are regularly seen from the shore and boats. Both grey and common seals come close to the shore to feed, rest, and raise their pups; a significant population over-winters on small islands in the Thurso river only a short walk from the town centre. Otters can be seen close to river mouths in some of the quieter locations.

Much of the centre of Caithness is known as the Flow Country, a large, rolling expanse of peatland and wetland that is the largest expanse of blanket bog in Europe. Around 1,500 km2 (580 sq mi) of the Flow Country is protected as both a Special Protection Area (SPA) and Special Area of Conservation (SAC) under the name Caithness and Sutherland Peatlands,[5][6] and a portion is further designated as the Forsinard Flows national nature reserve.[7]

In 2014 44 square miles (110 km2) of the eastern coastline of Caithness between Helmsdale and Wick was declared a Nature Conservation Marine Protected Area under the title East Caithness Cliffs.[8] The cliffs are also designated as both a Special Protection Area and a Special Area of Conservation.[9][10]

Early history

The Caithness landscape is rich with the remains of pre-historic occupation. These include the Grey Cairns of Camster, the Stone Lud, the Hill O Many Stanes, a complex of sites around Loch Yarrows and over 100 brochs. A prehistoric souterrain structure at Caithness has been likened to discoveries at Midgarth and on Shapinsay.[11] Numerous coastal castles (now mostly ruins) are Norwegian (West Norse) in their foundations.[12] When the Norsemen arrived, probably in the tenth century, the county was inhabited by the Picts,[13] but with its culture subject to some Goidelic influence from the Celtic Church. The name Pentland Firth can be read as meaning Pictland Fjord.

Numerous bands of Norse settlers landed in the county, and gradually established themselves around the coast. On the Latheron (south) side, they extended their settlements as far as Berriedale. Many of the names of places are Norse in origin.[14] In addition, some Caithness surnames, such as Gunn, are Norse in origin.[15]

For a long time, sovereignty over Caithness was disputed between Scotland and the Norwegian Earldom of Orkney. Around 1196, Earl Harald Maddadsson agreed to pay a monetary tribute for Caithness to William I. Norway has recognised Caithness as fully Scottish since the Treaty of Perth in 1266.

The study of Caithness prehistory is well represented in the county by groups including Yarrows Heritage Trust,[16] Caithness Horizons[17] and Caithness Broch Project.

Local government

Early civic history

.jpg.webp)

Caithness originally formed part of the shire or sheriffdom of Inverness, but gradually gained independence: in 1455 the Earl of Caithness gained a grant of the justiciary and sheriffdom of the area from the Sheriff of Inverness. In 1503 an act of the Parliament of Scotland confirmed the separate jurisdiction, with Dornoch and Wick named as burghs in which the sheriff of Caithness was to hold courts. The area of the sheriffdom was declared to be identical to that of the Diocese of Caithness. The Sheriff of Inverness still retained power over important legal cases, however, until 1641. In that year, parliament declared Wick the head burgh of the shire of Caithness and the Earl of Caithness became the heritable sheriff.[18] Following the Act of Union of 1707, the term "county" began to be applied to the shire, a process that was completed with the abolition of heritable jurisdictions in 1747.[19][20]

The population by 1841 had reached 36,343.[21]

The county began to be used as a unit of local administration, and in 1890 was given an elected county council under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1889. Although officially within the county, the burghs of Wick and Thurso retained their status as autonomous local government areas; they were already well established as autonomous burghs with their own burgh councils. Ten parish councils covering rural areas were established in 1894.

Wick, a royal burgh, served as the county's administrative centre. The county council was based at the County Offices, 73, 75 and 77 High Street, Wick.[22]

In 1930, the parish councils were abolished under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1929.

1975–96

In 1975, the Local Government council and the burgh councils were superseded under the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973 when Caithness became one of eight districts, each with its own "district council", within the new two-tier Highland region. When created, the district included the whole of the county plus Tongue and Farr areas of the neighbouring county of Sutherland. The boundary was soon changed, however, to correspond with that between the counties. Caithness was one of eight districts in the Highland region.

Highland region was also created in 1975, as one of nine two-tier local government regions of Scotland. Each region consisted of a number of districts and both regions and districts had their own elected councils. The creation of the Highland region and of Caithness as a district involved the abolition of the two burgh councils in Caithness, Wick and Thurso, as well as the Caithness county council.

Wick, which had been the administrative centre for the county, became the administrative centre for the district.

In 1996 local government in Scotland was again reformed, under the Local Government etc (Scotland) Act 1994, to create 32 unitary council areas. The Highland region became the Highland unitary council area, and the functions of the district councils were absorbed by the Highland Council.

1996 to 2007

In 1996, Caithness and the other seven districts of the Highland region were merged into the unitary Highland council area, under the Local Government etc (Scotland) Act 1994. The new Highland Council then adopted the former districts as management areas and created a system of area committees to represent the management areas.

Until 1999 the Caithness management and committee areas consisted of 8 out of the 72 Highland Council wards. Each ward elected one councillor by the first past the post system of election.

In 1999, however, ward boundaries were redrawn but management area boundaries were not. As a result, area committees were named after and made decisions for areas which they did not exactly represent. The new Caithness committee area, consisting of ten out of the 80 new Highland Council wards, did not include the village of Reay, although that village was within the Caithness management area. For area committee representation the village was within the Sutherland committee area.

New wards were created for elections this year, 2007, polling on 3 May and, as the wards became effective for representational purposes, the Highland Council's management and committee structures were reorganised. The Caithness management area and the Caithness area committee were therefore abolished.

2007 to date

In 2007 the Highland Council, which is now the local government authority, created the Caithness ward management area, which has boundaries similar to those of the historic county. It was divided between three new wards electing councillors by the single transferable vote system of election, which is designed to produce a form of proportional representation. One ward elects four councillors. Each of the other two elects three councillors. Also, the council's eight management areas were abolished, in favour of three new corporate management areas, with Caithness becoming a ward management area within the council's new Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross operational management area, which covers seven of the council's 22 new wards. The boundaries of the Caithness ward management area are not exactly those of the former Caithness management area, but they do include the village of Reay.

The ward management area is one of five within the corporate management area and until 2017 consisted of three wards, the Landward Caithness ward, the Thurso ward and the Wick ward. Each of the other ward management areas within the corporate management area consists of a single ward. In 2017 the three Caithness wards were reduced to two 'Town and County' wards, each returning four members to the Highland Council,[23] this was a reduction of two Councillors from the last election in 2012. The new wards are Thurso and Northwest Caithness[24] and Wick and East Caithness.[25]

Since 4 May 2017 Caithness has been represented by four Independent Councillors, two Scottish Conservative Councillors and two Scottish National Party Councillors. The current Chairman of the Caithness Committee is Donnie Mackay (Independent) and the Civic Leader position is held by A.I Willie Mackay (Independent) both being installed on 16 June 2017 at the first Caithness Committee of the new council.[26]

Parishes

Prior to implementation of the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1889, civil administration parishes were also parishes of the Church of Scotland, and one Caithness parish, Reay, straddled the boundary between the county of Caithness and the county of Sutherland, and another, Thurso had a separate fragment bounded by Reay and Halkirk. For civil administration purposes, implementation of the act redefined parish boundaries, transferring part of Reay to the Sutherland parish of Farr and the fragment of Thurso to the parish of Halkirk.[27]

In the cases of two of the parishes, Thurso and Wick, each includes a burgh with the same name as the parish. For civil administration purposes each of these parishes was divided between the burgh and the landward (rural) area of the parish.

Civil parishes are still used for some statistical purposes, and separate census figures are published for them. As their areas have been largely unchanged since the nineteenth century this allows for comparison of population figures over an extended period of time.

| Civil parish | Area in 1930 (hectares) |

Census 2001-03-27 |

Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Bower | 10,032 | 633 | Has the Stone Lud near its geographic centre |

| 2 Canisbay | 10,098 | 927 | Includes the village of John o' Groats and the Island of Stroma |

| 3 Dunnet | 5,241 | 582 | Includes the village of Dunnet and Dunnet Head |

| 4 Halkirk | 38,492 | 1,460 | Includes the village of Halkirk |

| 5 Latheron | 49,088 | 1,805 | Includes the villages of Latheron, Lybster and Dunbeath |

| 6 Olrig | 4,547 | 1,269 | Includes the village of Castletown |

| 7 Reay | 18,452 | 694 | Includes the village of Reay Was, at one time, partly in the county of Sutherland |

| 8 Thurso Landward | 10,871 | 9,112 | A rural area around the burgh of Thurso |

| 9 Watten | 14,182 | 749 | Includes the village of Watten |

| 10 Wick Landward | 19,262 | 9,255 | A rural area around the burgh of Wick |

| Caithness County totals | 180,265 | 26,486 |

Halkirk was formed at the Reformation by the merger of the ancient parishes of Halkirk and Skinnet.[28] Watten was created from part of Bower parish in 1638.[29]

Community councils, 1975 to 2008

Although created under local government legislation (the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1973) community councils have no statutory powers or responsibilities and are not a tier of local government. They are however the most local tier of statutory representation.

Under the 1973 Act, district councils were obliged to implement community council schemes. A Caithness district scheme was adopted in 1975, dividing the area of the district between 12 community councils.

Statutory status for community councils was continued under the Local Government etc (Scotland) Act 1994, and a Caithness scheme is now the responsibility of the Highland Council.

The area of the former district of Caithness is now covered by 12 community council areas which are numbered and described as below in the Highland Council's Scheme for the Establishment of Community Councils in Caithness, October 1997. Current community council names and contact details are given on a Highland Council website.[30]

- 1. Royal Burgh of Wick

- 2. Sinclair's Bay (including Keiss, Reiss and part of Wick)

- 3. Dunnet and Canisbay

- 4. Bower (excluding Gelshfield area)

- 5. Watten (including part of Bower i.e. Gelshfield area)

- 6. Wick south-east, Wick south-west and part of Clyth (i.e. Bruan) (Tannach & District)

- 7. Latheron, Lybster and remainder of Clyth (including Occumster, Roster and Camster)

- 8. Berridale and Dunbeath

- 9. Thurso

- 13. Halkirk south, Halkirk north-east, Halkirk north-west (excluding Lieurary, Forsie and Westfield area)

- 14. Castletown, Olrig, Thurso east (excluding area on west side of Thurso River)

- 15. Caithness West (that part on the west side of Thurso River only), Thurso West, Reay and part of Halkirk north-west (that part comprising Lieurary, Forsie and Westfield area)

Parliamentary constituency

The Caithness constituency of the House of Commons of the Parliament of Great Britain (1708 to 1801) and the Parliament of the United Kingdom (1801 to 1918) represented essentially the county from 1708 to 1918. At the same time however, the county town of Wick was represented as a component of Tain Burghs until 1832 and of Wick Burghs until 1918.

Between 1708 and 1832 the Caithness constituency was paired with Buteshire as alternating constituencies: one constituency elected a member of parliament (MP) to one parliament and then the other elected an MP to the next. Between 1832 and 1918 Caithness elected an MP to every parliament.

In 1918 the Caithness constituency and Wick were merged into the then new constituency of Caithness and Sutherland. In 1997 Caithness and Sutherland was merged into Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross.

The Scottish Parliament constituency of Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross was created in 1999 and now has boundaries slightly different from those of the House of Commons constituency. It was replaced by the larger constituency of Caithness, Sutherland and Ross in 2011.

The modern constituencies may be seen as more sub-divisions of the Highland area than as representative of counties (and burghs). For its own purposes, however, the Highland Council uses more conservative sub-divisions, with names which refer back to the era of district councils and, in some cases, county councils.

In the Scottish Parliament Caithness is represented also as part of the Highlands and Islands electoral region.

Towns and villages

In 2011, Caithness had a resident population of 26,486 (23,866 in 2001).

There are two towns in Caithness: Thurso and Wick.

There are also a few villages large enough to have amenities such as a shop, a cafe, a post office, a hotel, a church or a bank. These include Castletown, Dunbeath, Dunnet, Halkirk, John o' Groats, Keiss, Lybster, Reay/New Reay, Scrabster and Watten.

Other, smaller settlements include:

- Achingills

- Achreamie

- Achvarasdal

- Ackergill

- Altnabreac

- Auckengill

- Balnabruich

- Berriedale

- Bilbster

- Borgue

- Bower

- Brabsterdorran

- Braemore

- Broubster

- Brough

- Bruan

- Buldoo

- Bullavrochan

- Burnside

- Caberfeidh

- Canisbay

- Clyth

- Crosskirk

- Dorrery

- East May

- Forss

- Fresgoe

- Freswick

- Gillock

- Gills

- Ham

- Harrow

- Haster

- Houstry

- Huna

- Killimster

- Landhallow

- Latheron

- Latheronwheel

- Lower Smerral

- Mey

- Morven (the highest point of Caithness)

- Murkle

- Mybster

- Newlands of Geise

- Newport, Caithness

- Papigoe

- Ramscraig

- Reaster

- Reiss

- Roadside

- Roster

- Sarclet

- Scarfskerry

- Shebster

- Sibster

- Skirza

- Smerral

- Sordale

- Spittal

- Staxigoe

- Swiney

- Thrumster

- Ulbster

- Upper Camster

- Upper Lybster

- Westerdale

- Westfield

- Weydale

- Whiterow

Transport

Caithness is served by the Far North railway line, which runs west–east across the middle of the county serving Altnabreac and Scotscalder before splitting in two at Georgemas Junction, from where the east branch continues to Wick whilst the north branch terminates at Thurso.

Stagecoach Group provided bus transport between the major towns, and on to Inverness via Sutherland and Ross-shire.[31]

The ferry port at Scrabster provides a regular service to Stromness in the Orkney Islands. Ferries also run from Gills Bay to St Margaret's Hope on South Ronaldsay. A summer-only ferry runs from John o' Groats to Burwick on South Ronaldsay.

Wick Airport provided regular flights to Aberdeen and Edinburgh until 2020 when Loganair and Eastern Airways cancelled their flights.[32] In 2021 there were no scheduled flights to and from Wick Airport. Starting on 11 April 2022, Eastern Airways started a scheduled operation to Wick from Aberdeen.[33]

Language

At the beginning of recorded history, Caithness was inhabited by the Picts, whose language Pictish is thought to have been related to the Brythonic languages spoken by the Britons to the south. The Norn language was introduced to Caithness, Orkney, and Shetland by the Norse occupation, which is generally proposed to be c. AD 800.[34] Although little is known of that Norn dialect, some of this linguistic influence still exists in parts of the county, particularly in place names. Norn continued to be spoken in Caithness until perhaps the fifteenth century[35] and lingered until the late eighteenth century in the Northern Isles.

It is sometimes erroneously claimed that Gaelic has never been spoken in Caithness, but this is a result of language shift to Scots,[36][37][38][39][40][41] and then towards Standard Scottish English during recent centuries.[42] The Gaelic name for the region, Gallaibh, translates as "Land of the Gall (non-Gaels)", a name which reflects historic Norse rule. Gaelic speakers seem to first figure in the early stage of the Scandinavian colonisation of Caithness, gradually increasing in numerical significance from the 12th century onwards.[43] Gaelic has survived, in a limited form, in western parts of the county.[42]

Scots began supplanting Norn in the early fourteenth century at the time of the Wars of Scottish Independence.[44] The emergent Northern Scots dialect became influenced by both Gaelic and Norn[45] and is generally spoken in the lowlying land to the east of a line drawn from Clyth Ness to some 4 miles (6 km) west of Thurso.[46] The dialect of Scots spoken in the neighbourhood of John o' Groats resembles to some extent that of Orkney. Since the seventeenth century, Standard Scottish English has increasingly been replacing both Gaelic and Scots.

Records showing what languages were spoken apparently do not exist from before 1706, but by that time, "[I]f ye suppose a Parallel to the hypotenuse drawn from Week to Thurso, these on the Eastside of it speak most part English, and those on the Westside Irish; and the last have Ministers to preach to them in both languages." Similarly, it is stated at that time that there were "Seven parishes [out of 10 or 11] in [the Presbytery of] Caithness where the Irish language is used."[47]

As previously indicated, the language mix or boundary changed over time, but the New Statistical Record in 1841 says: "On the eastern side of [the Burn of East Clyth] scarcely a word of Gaelic was either spoken or understood, and on the west side, English suffered the same fate". Other sources state:

- "There are Seven parishes in [the Presbytery of] Caithness where the Irish language is used, viz. Thurso, Halkrig [Halkirk], Rhae [Reay], Lathrone [Latheron], Ffar [Farr], Week [Wick], Duirness [Durness]. But the people of Week understand English also." (Presbytery of Caithness, 1706)[47]

- "A presbytery minute of 1727 says of 1,600 people who had 'come of age', 1500 could speak Gaelic only, and a mere five could read. Gaelic at this time was the principal language in most parishes except Bower, Canisbay, Dunnet and Olrig".[48]

- "Persons with a knowledge of Gaelic in the County of Caithness (in 1911) are found to number 1,685, and to constitute 6.7 per cent of the entire population of three years of age and upwards. Of these 1,248 were born in Caithness, 273 in Sutherland, 77 in Ross & Cromarty, and 87 elsewhere.... By an examination of the age distribution of the Gaelic speakers, it is found that only 22 of them are less than 20 years of age."[49]

According to the 2011 Scotland Census, 282 (1.1%) residents of Caithness age three and over can speak Gaelic while 466 (1.8%) have some facility with the language. The percentage figures are almost exactly the same as for all of Scotland (1.1% and 1.7%, respectively).[50] Nearly half of all Gaelic speakers in the county live in Thurso civil parish. The town of Thurso hosts the only Gaelic-medium primary school unit in all of Caithness (see Language in Thurso).

The bilingual road sign policy of Highland Region Council has led to some controversy in the region. In 2008, eight of the ten Caithness representatives to the Highland Council tried to prevent the introduction of bilingual English-Gaelic road signs into the county.[51] The first bilingual sign in Caithness was erected in 2012.[52] In 2013, a bilingual road sign on the A99 road next to Wick Airport was damaged by gunfire within 24 hours of it being placed. Gaelic-speaking Councillor Alex MacLeod, at the time representing Landward Caithness in the Highland Council, referred to it as "an extreme anti-Gaelic incident".[53]

Local media

Newspapers

The John O'Groat Journal and The Caithness Courier are weekly newspapers published by Scottish Provincial Press Limited[54] trading as North of Scotland Newspapers[55] and using offices in Union Street, Wick (but with public reception via Cliff Road) and Olrig Street, Thurso.

News coverage tends to concentrate on the former counties of Caithness and Sutherland. The John O'Groat Journal is normally published on Fridays and The Caithness Courier on Wednesdays. The two papers share a website.[56]

Historically, they have been independent newspapers, with the Groat as a Wick-centred paper and the Courier as a Thurso-centred paper. Even now, the Groat is archived in the public library in Wick, while the Courier is similarly archived in the library in Thurso. The Courier was printed, almost by hand, in a small shop in High Street, Thurso until the early 60's by Mr Docherty and his daughter. The Courier traditionally covers that week's cases at Wick Sheriff Court.[57]

Radio

Caithness FM has been broadcasting since 1993 and the Orkney Commercial Radio, Superstation Orkney from Kirkwall from 2004 to 2014.[58]

See also

Constituencies

- Caithness (UK Parliament constituency) (1708 to 1918)

- Tain Burghs (UK Parliament constituency) (1708 to 1832)

- Wick Burghs (UK Parliament constituency) (1832 to 1918)

- Caithness and Sutherland (UK Parliament constituency) (1918 to 1997)

- Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross (UK Parliament constituency) (1997 to present)

- Caithness, Sutherland and Easter Ross (Scottish Parliament constituency) (1999 to 2011)

- Caithness, Sutherland and Ross (Scottish Parliament constituency) (2011 to present)

Other

- Caithness Broch Project

- Caithness Glass

- Clan Gunn

- Clan Sinclair

- Counties of Scotland

- List of counties of Scotland 1890–1975

- Local government in Scotland

- Local government areas of Scotland 1973 to 1996

- Maiden Paps, Caithness

- Medieval Diocese of Caithness

- Politics of the Highland council area

- Subdivisions of Scotland

References

- ↑ "Index: C". British History Online. Institute of Historical Research and the History of Parliament Trust. Archived from the original on 3 August 2017.

- 1 2 3 Gaelic and Norse in the Landscape: Placenames in Caithness and Sutherland Archived 21 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Scottish National Heritage. pp.7–8.

- ↑ "Norn omniglot". Archived from the original on 25 January 2023. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ↑ ALISTAIRMUNRO. 2017. VIDEO: Amazing footage of pilot whales and Risso’s dolphins off the coast of Caithness Archived 30 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine. The Press and Journal. 30 September 2017

- ↑ "Caithness and Sutherland Peatlands SPA". Scottish Natural Heritage. Archived from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ↑ "Caithness and Sutherland Peatlands SAC". Scottish Natural Heritage. Archived from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

- ↑ "Forsinard Flows National Nature Reserve". Scottish Natural Heritage. Archived from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ↑ "East Caithness Cliff MPA(NC)". Scottish Natural Heritage. Archived from the original on 16 August 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ↑ "East Caithness Cliffs SPA". Scottish Natural Heritage. Archived from the original on 27 September 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- ↑ "East Caithness Cliffs SAC". Scottish Natural Heritage. Archived from the original on 27 September 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- ↑ "C.Michael Hogan, Castle bloody, The Megalithic Portal, ed. A. Burnham, 2007". Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2008.

- ↑ Scholarly essays in J.R. Baldwion and I.D. Whyte, eds. The Viking Age in Caithness, Orkney and the North Atlantic (Edinburgh University Press) 1993, give an overview.

- ↑ "Priests and Picts". Caithness Archaeology. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ↑ Logan, F. Donald (2005). The Vikings in History (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge. p. 28. ISBN 9781136527098. Archived from the original on 17 November 2023. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ↑ MacBain, Alexander (1922). Place Names Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Stirling: Mackay. p. 21. ISBN 978-1179979427. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ↑ "Yarrows Heritage Trust – Home". yarrowsheritagetrust.co.uk. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ↑ "Caithness Horizons Museum". Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2017.

- ↑ Campbell, H F (1920). Caithness & Sutherland. Cambridge County Geographies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Whetstone, Ann E. (1977). "The Reform of the Scottish Sheriffdoms in the Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries". Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies. The North American Conference on British Studies. 9 (1): 61–71. doi:10.2307/4048219. JSTOR 4048219.

- ↑ Whatley, Christopher A (2000). Scottish Society 1707–1820. Manchester University Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-7190-4540-0.

- ↑ The National Cyclopaedia of Useful Knowledge, Vol.IV, (1848), London, Charles Knight, p.16

- ↑ Historic Environment Scotland. "County Council Offices, 73, 75 & 77 High Street, Wick (LB48834)". Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ↑ Butlin, Heather. "Council wards". highland.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ↑ Butlin, Heather. "Council ward information". highland.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ↑ Butlin, Heather. "Council ward information". highland.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ↑ Tarrant, Sylvia. "Caithness Committee Chair and Civic Leader appointed". highland.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ↑ Boundary changes as described in Boundaries of Counties and Parishes in Scotland, Hay Shennan, 1892

- ↑ GENUKI. "Genuki: Halkirk, Caithness". genuki.org.uk. Archived from the original on 4 February 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ↑ GENUKI. "Genuki: Watten, Caithness". genuki.org.uk. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ↑ "Community 03 March 2008, accessed 3 March 2008" (PDF). Highland Council website. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 October 2007. Retrieved 3 March 2008.

- ↑ "Stagecoach North Scotland – Caithness and Sutherland Area Guide from 20 August 2018" (PDF). Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ↑ "Destinations". HIAL. Archived from the original on 25 October 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- ↑ "Destinations". HIAL. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- ↑ The Viking age in Caithness, Orkney and the North Atlantic, Edinburgh University Press ISBN 0-7486-0430-8, page 121

- ↑ Jones, Charles (1997). The Edinburgh history of the Scots language. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 394.

- ↑ Jamieson, J. (1808), An Etymological Dictionary of the Scottish Language.

- ↑ The New Statistical Account of Scotland (1845) Vol. XV

- ↑ Transactions of the Hawick Archaeological Society (1863)

- ↑ Murray, James A. H. (1873) The Dialect of the Southern Counties of Scotland, Transactions of the Philological Society, Part II, 1870–72. London-Berlin, Asher & Co.

- ↑ Grant, William; Dixon, James Main (1921) Manual of Modern Scots. Cambridge, University Press.

- ↑ The Scottish National Dictionary (1929–1976) vol. I

- 1 2 "1901–2001 – Gaelic in the Census" (ppt). linguae-celticae.org. Archived from the original on 7 December 2010. Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- ↑ The Viking age in Caithness, Orkney and the North Atlantic, Edinburgh University Press ISBN 0-7486-0430-8, page 125

- ↑ Mairi Robinson (editor-in-chief), The Concise Scots Dictionary, Aberdeen University Press, 1985 p.x

- ↑ McColl Millar. 2007. Northern and Insular Scots. Edinburgh: University Press Ltd. p. 191

- ↑ "SND Introduction". Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- 1 2 Caithness of the Gael and the Lowlander Archived 8 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Omand, D. From the Vikings to the Forty-Five, in The Caithness book.

- ↑ J. Patten MacDougall, Registrar General, 1912

- ↑ 2011 Scotland Census Archived 4 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Table QS211SC.

- ↑ "Bid to exclude Gaelic signs fails Archived 31 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine", BBC News, 6 March 2008.

- ↑ Gordon Calder, "New bilingual sign sparks fresh wrangle Archived 31 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine," John O'Groat Journal, 10 August 2012.

- ↑ Alisdair Munro, "‘Anti-Gaelic gunmen’ shoot road sign in Caithness Archived 12 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine", The Scotsman, 5 September 2013.

- ↑ "Scottish Provincial Press Limited website". Archived from the original on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 28 June 2007.

- ↑ "Services North – Search for local businesses in the North of Scotland". Caithness Courier. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 28 June 2007.

- ↑ "John O'Groat Journal – Home". johnogroat-journal.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 October 2017. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ↑ "Courts". John O'Groat Journal and Caithness Courier. Archived from the original on 25 December 2022. Retrieved 25 December 2022.

- ↑ "Caithness FM". Archived from the original on 16 February 2009. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

External links

- Caithness Community Website

- Caithness Dialect Archived 4 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Caithness Dialect at Scots Language Centre

- Caithness Arts website

- Castletown and District Community Council website

- Castletown Heritage Society

- Dunnet and Canisbay Community Council

- Castle of Mey website

- Castle Sinclair Girnigoe

- Caithness forum

- Caithness alternative community forum

- Caithness Broch Project