Roughly 400 known ogham inscriptions are on stone monuments scattered around the Irish Sea, the bulk of them dating to the fifth and sixth centuries. Their language is predominantly Primitive Irish, but a few examples record fragments of the Pictish language. Ogham itself is an Early Medieval form of alphabet or cipher, sometimes known as the "Celtic Tree Alphabet".

A number of different numbering schemes are used. The most widespread is CIIC, after R. A. S. Macalister (Corpus Inscriptionum Insularum Celticarum, Latin for "corpus of Insular Celtic inscriptions"). This covers the inscriptions known by the 1940s. Another numbering scheme is that of the Celtic Inscribed Stones Project, CISP, based on the location of the stones; for example CIIC 1 = CISP INCHA/1. Macalister's (1945) numbers run from 1 to 507, including also Latin and Runic inscriptions, with three additional added in 1949. Ziegler lists 344 Gaelic ogham inscriptions known to Macalister (Ireland and Isle of Man), and seven additional inscriptions discovered later.

The inscriptions may be divided into "orthodox" and "scholastic" specimens. "Orthodox" inscriptions date to the Primitive Irish period, and record a name of an individual, either as a cenotaph or tombstone, or documenting land ownership. "Scholastic" inscriptions date from the medieval Old Irish period up to modern times.

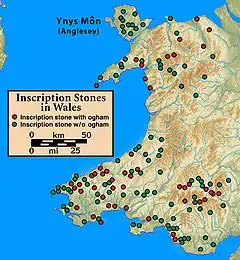

The vast bulk of the surviving ogham inscriptions stretch in an arc from County Kerry (especially Corcu Duibne) in the south of Ireland across to Dyfed in south Wales. The remainder are mostly in south-eastern Ireland, eastern and northern Scotland, the Isle of Man, and England around the Devon/Cornwall border. The vast majority of the inscriptions consists of personal names, probably of the person commemorated by the monument.

Orthodox inscriptions

| Ogham letters ᚛ᚑᚌᚐᚋᚁᚂᚃᚓᚇᚐᚅ᚜ | |||||

| Aicme Beithe ᚛ᚐᚔᚉᚋᚓᚁᚂᚃᚄᚅ᚜ |

Aicme Muine ᚛ᚐᚔᚉᚋᚓᚋᚌᚎᚏ᚜ | ||||

| ᚁ | [b] | Beith | ᚋ | [m] | Muin |

| ᚂ | [l] | Luis | ᚌ | [ɡ] | Gort |

| ᚃ | [w] | Fearn | ᚍ | [ɡʷ] | nGéadal |

| ᚄ | [s] | Sail | ᚎ | [st], [ts], [sw] | Straif |

| ᚅ | [n] | Nion | ᚏ | [r] | Ruis |

| Aicme hÚatha ᚛ᚐᚔᚉᚋᚓᚆᚇᚈᚉᚊ᚜ |

Aicme Ailme ᚛ᚐᚔᚉᚋᚓᚐᚑᚒᚓᚔ᚜ | ||||

| ᚆ | [j] | Uath | ᚐ | [a] | Ailm |

| ᚇ | [d] | Dair | ᚑ | [o] | Onn |

| ᚈ | [t] | Tinne | ᚒ | [u] | Úr |

| ᚉ | [k] | Coll | ᚓ | [e] | Eadhadh |

| ᚊ | [kʷ] | Ceirt | ᚔ | [i] | Iodhadh |

| Forfeda ᚛ᚃᚑᚏᚃᚓᚇᚐ᚜ (rare, sounds uncertain) |

᚛ᚕᚖᚗᚘᚚᚙ᚜ | ||||

| ᚕ | [ea], [k], [x], [eo] | Éabhadh | |||

| ᚖ | [oi] | Ór | |||

| ᚗ | [ui] | Uilleann | |||

| ᚘ | [ia] | Ifín | ᚚ | [p] | Peith |

| ᚙ | [x], [ai] | Eamhancholl | |||

In orthodox inscriptions, the script was carved into the edge (droim or faobhar) of the stone, which formed the stemline against which individual characters are cut. The text of these "Orthodox Ogham" inscriptions is read beginning from the bottom left side of a stone, continuing upward along the edge, across the top and down the right side (in the case of long inscriptions).

MacManus (1991) lists a total of 382 known Orthodox inscriptions. They are found in most counties of Ireland but are concentrated in southern Ireland, with the highest numbers found in County Kerry (130), Cork (84), and Waterford (48). Other counts are as follows: Kilkenny (14); Mayo (9); Kildare (8); Wicklow and Meath (5 each); Carlow (4); Wexford, Limerick, and Roscommon (3 each); Antrim, Cavan, Louth, and Tipperary (2 each); Armagh, Dublin, Fermanagh, Leitrim, Londonderry and Tyrone (1 each).

Other specimens are known from Wales (ca. 40: Pembrokeshire (16); Breconshire and Carmarthenshire (7 each); Glamorgan (4); Cardiganshire (3); Denbighshire (2); Powys (1), and Caernarvonshire (1)). A few are known of from sites in the Isle of Man (5), in England, such as Cornwall (5), Devon (2), and some doubtful examples from Scotland (possibly 2).

Formula words

The vast majority of inscriptions consists of personal names and use a series of formula words, usually describing the person's ancestry or tribal affiliation.

Formula words used include the following:

- MAQI ᚋᚐᚊᚔ – 'son' (Modern Irish mac)

- MUCOI ᚋᚒᚉᚑᚔ – 'tribe' or 'sept'

- ANM ᚐᚅᚋ – 'name' (Modern Irish ainm)

- AVI ᚐᚃᚔ – 'descendant' (Modern Irish uí)

- CELI ᚉᚓᚂᚔ – 'follower' or 'devotee' (Modern Irish céile)

- NETA ᚅᚓᚈᚐ – 'nephew' (Modern Irish nia)

- KOI ᚕᚑᚔ – 'here is' (equivalent to Latin HIC IACIT). KOI is unusual in that the K is always written using the first supplementary letter Ebad.

In order of frequency, the formula words are used as follows:

- X MAQI Y (X son of Y)

- X MAQI MUCOI Y (X son of the tribe Y)

- X MAQI Y MUCOI Z (X son of Y of the tribe Z)

- X KOI MAQI MUCOI Y (here is X son of the tribe Y)

- X MUCOI Y (X of the tribe Y)

- X MAQI Y MAQI MUCOI Z (X son of Y son of the tribe Z)

- Single name inscriptions with no accompanying formula word

- ANM X MAQI Y (Name X son of Y)

- ANM X (Name X )

- X AVI Y (X descendant of Y)

- X MAQI Y AVI Z (X son of Y descendant of Z)

- X CELI Y (X follower/devotee of Y)

- NETTA X (nephew/champion of X)

Nomenclature

The nomenclature of the Irish personal names is more interesting than the rather repetitive formulae and reveals details of early Gaelic society, particularly its warlike nature.

For example, two of the most commonly occurring elements in the names are CUNA ᚉᚒᚅᚐ – 'hound' or 'wolf' (Modern Irish cú) and CATTU ᚉᚐᚈᚈᚒ – 'battle' (Modern Irish cath).

These occur in names such as (300) CUNANETAS ᚉᚒᚅᚐᚅᚓᚈᚐᚄ – 'Champion of wolves'; (501) CUNAMAGLI ᚉᚒᚅᚐᚋᚐᚌᚂᚔ – 'prince of wolves'; (107) CUNAGUSSOS ᚉᚒᚅᚐᚌᚒᚄᚄᚑᚄ – '(he who is) strong as a wolf'; (250) CATTUVVIRR ᚉᚐᚈᚈᚒᚃᚃᚔᚏᚏ – 'man of battle'; (303) CATABAR ᚉᚐᚈᚐᚁᚐᚏ – 'chief in battle'; IVACATTOS ᚔᚃᚐᚉᚐᚈᚈᚑᚄ – 'yew of battle'.

Other warlike names include (39) BRANOGENI ᚁᚏᚐᚅᚑᚌᚓᚅᚔ – 'born of raven'; (428) TRENAGUSU ᚈᚏᚓᚅᚐᚌᚒᚄᚒ – 'strong of vigour'; and (504) BIVAIDONAS ᚁᚔᚃᚐᚔᚇᚑᚅᚐᚄ – 'alive like fire'.

Elements that are descriptive of physical characteristics are also common, such as (368) VENDUBARI ᚃᚓᚅᚇᚒᚁᚐᚏᚔ – 'fair-headed'; (75) CASONI ᚉᚐᚄᚑᚅᚔ – 'curly headed one'; (119) DALAGNI ᚇᚐᚂᚐᚌᚅᚔ – 'one who is blind'; (46) DERCMASOC ᚇᚓᚏᚉᚋᚐᚄᚑᚉ – 'one with an elegant eye'; (60) MAILAGNI ᚋᚐᚔᚂᚐᚌᚅᚔ – 'bald/short haired one' and (239) GATTAGLAN ᚌᚐᚈᚈᚐᚌᚂᚐᚅ – 'wise and pure'.

Other names indicate a divine ancestor. The god Lugh features in many names such as (4) LUGADDON ᚂᚒᚌᚌᚐᚇᚑᚅ, (286) LUGUDECA ᚂᚒᚌᚒᚇᚓᚉᚐ and (140) LUGAVVECCA ᚂᚒᚌᚐᚃᚃᚓᚉᚉᚐ, while the divine name ERC (meaning either 'heaven or 'cow') appears in names such as (93) ERCAIDANA ᚓᚏᚉᚐᚔᚇᚐᚅᚐ and (196) ERCAVICCAS ᚓᚏᚉᚐᚃᚔᚉᚉᚐᚄ.

Other names indicate sept or tribal name, such as (156) DOVVINIAS ᚇᚑᚃᚃᚔᚅᚔᚐᚄ from the Corcu Duibne sept of the Dingle and Iveragh peninsulas in County Kerry (named after a local goddess); (215) ALLATO ᚐᚂᚂᚐᚈᚑ from the Altraige of North Kerry and (106) CORIBIRI ᚉᚑᚏᚔᚁᚔᚏᚔ from the Dál Coirpri of County Cork.

Of particular interest is the fact that quite a few names denote a relationship to trees, such as (230) MAQI-CARATTINN ᚋᚐᚊᚔ ᚉᚐᚏᚐᚈᚈᚔᚅᚅ – 'son of rowan'; (v) MAQVI QOLI ᚋᚐᚊᚃᚔ ᚊᚑᚂᚔ – 'son of hazel' and (259) IVOGENI ᚔᚃᚑᚌᚓᚅᚔ – 'born of yew'.

The content of the inscriptions has led scholars such as McNeill and Macalister to argue that they are explicitly pagan in nature. They argue that the inscriptions were later defaced by Christian converts, who deliberately removed the word MUCOI ᚋᚒᚉᚑᚔ on account of its supposedly pagan associations and added crosses next to them.

Other scholars, such as McManus, argue that there is no evidence for this, citing inscriptions such as (145) QRIMITIR RONANN MAQ COMOGANN ᚛ᚊᚏᚔᚋᚔᚈᚔᚏ ᚏᚑᚅᚐᚅᚅ ᚋᚐᚊ ᚉᚑᚋᚑᚌᚐᚅᚅ᚜, where QRIMITIR is a loan word from Latin presbyter or 'priest'. McManus argues that the supposed vandalism of the inscriptions is simply wear and tear, and due to the inscription stones being reused as building material for walls, lintels, etc. (McManus, §4.9). McManus also argues that the MUCOI formula word survived into Christian manuscript usage. There is also the fact the inscriptions were made at a time when Christianity had become firmly established in Ireland. Whether those who wrote the inscriptions were pagans, Christians, or a mixture of both remains unclear.

Ireland

Ireland has the vast majority of inscriptions, with 330 out of 382. One of the most important collections of orthodox ogham inscriptions in Ireland can be seen in University College Cork (UCC) on public display in 'The Stone Corridor'. The inscriptions were collected by antiquarian Abraham Abell 1783–1851 and were deposited in the Cork Institution before being put on display in UCC. He was a member of the Cuvierian Society of Cork whose members, including John Windele, Fr. Matt Horgan and R.R. Brash, did extensive work in this area in the mid-19th century.

Another well-known group of inscriptions, known as the Dunloe Ogham Stones, can be seen at Dunloe near Killarney in County Kerry. The inscriptions are arranged in a semicircle at the side of the road and are very well preserved.

| ID | Text | Translation / Personal names | Location | Notes |

| CIIC 1 | ᚛ᚂᚔᚓ ᚂᚒᚌᚅᚐᚓᚇᚑᚅ ᚋᚐᚉᚉᚔ ᚋᚓᚅᚒᚓᚆ᚜ LIE LUGNAEDON MACCI MENUEH | "The stone of Lugnaedon son of Limenueh". | Inchagoill island, County Galway | CISP INCHA/1[1] |

| CIIC 2 | ᚛ᚊᚓᚅᚒᚃᚓᚅᚇᚔ᚜ QENUVEN[DI] | Qenuvendi, "white head", corresponding to early names Cenond, Cenondÿn, Cenindÿn[2] See Cloonmorris Ogham stone | Bornacoola, County Leitrim | CISP CLOOM/1[3] |

| CIIC 3 | ᚛ᚉᚒᚅᚐᚂᚓᚌᚔ ᚐᚃᚔ ᚊᚒᚅᚐᚉᚐᚅᚑᚄ᚜ CUNALEGI AVI QUNACANOS | "Cunalegi, descendant of Qunacanos" | Island, Costello, County Mayo | CISP ISLAN/1[4] |

| CIIC 4 | ᚛ᚂᚒᚌᚐᚇᚇᚑᚅ ᚋᚐᚊᚔ ᚂᚒᚌᚒᚇᚓᚉ᚜ ᚛ᚇᚇᚔᚄᚔ ᚋᚑ[--]ᚉᚊᚒᚄᚓᚂ᚜ LUGADDON MA[QI] L[U]GUDEC DDISI MO[--]CQU SEL | Lugáed son of Luguid | Kilmannia, Costello | CISP KILMA/1[5] |

| CIIC 5 | ᚛ᚐᚂᚐᚈᚈᚑᚄ ᚋᚐᚊᚔ ᚁᚏ᚜ ALATTOS MAQI BR[ | Alattos son of Br... | Rusheens East, Kilmovee, Costello | CISP RUSHE/1[6] |

| CIIC 6 | ᚛ᚊᚐᚄᚔᚌᚔᚅᚔᚋᚐᚊᚔ᚜ QASIGN[I]MAQ[I] | Qasignias son of ... | Tullaghaun, Costello | CISP TULLA/1[7] |

| CIIC 7 | ᚛ᚋᚐᚊ ᚉᚓᚏᚐᚅᚔ ᚐᚃᚔ ᚐᚖᚓᚉᚓᚈᚐᚔᚋᚔᚅ᚜ MAQ CERAN[I] AVI ATHECETAIMIN[8] | Son of Ciarán, descendant of the Uí Riaghan | Corrower, Gallen, County Mayo | CISP CORRO/1[9] |

| CIIC 8 | ᚛ᚋᚐᚊᚔ ᚋᚒᚉᚑᚔ ᚉᚑᚏᚁᚐᚌᚅᚔ ᚌᚂᚐᚄᚔᚉᚑᚅᚐᚄ᚜ MA[QUI MUCOI] CORBAGNI GLASICONAS | Son of the tribe Corbagnus Glasiconas | Dooghmakeon, Murrisk, County Mayo | CISP DOOGH/1[10] |

| CIIC 9 | ᚛ᚋᚐᚊᚐᚉᚈᚑᚋᚐᚊᚌᚐᚏ᚜ MAQACTOMAQGAR | Son of Acto, son of Gar | Aghaleague, Tirawley, County Mayo | CISP AGHAL/1[11] Almost illegible |

| CIIC 10 | ᚛ᚂᚓᚌᚌ[--]ᚄᚇ[--]ᚂᚓᚌᚓᚄᚉᚐᚇ᚜ / ᚛ᚋᚐᚊ ᚉᚑᚏᚏᚁᚏᚔ ᚋᚐᚊ ᚐᚋᚋᚂᚂᚑᚌᚔᚈᚈ᚜ L[E]GG[--]SD[--] LEGwESCAD / MAQ CORRBRI MAQ AMMLLOGwITT | Legwescad, son of Corrbrias, son of Ammllogwitt | Breastagh, Tirawley | CISP BREAS/1[12] |

| CIIC 38 | ᚛ᚉᚑᚏᚁᚔᚕᚑᚔᚋᚐᚊᚔᚂᚐᚏᚔᚇ᚜ CORBI KOI MAQI LABRID | Here is Corb, son of Labraid | Ballyboodan, Knocktopher, County Kilkenny | [13] |

| CIIC 47 | ᚛ᚅᚓᚈᚐᚉᚐᚏᚔᚅᚓᚈᚐᚉᚉᚐᚌᚔ᚜ NETACARI NETA CAGI | Netacari, nephew of Cagi | Castletimon, Brittas Bay, County Wicklow | [14] |

| CIIC 50 | ᚛ᚃᚑᚈᚔ᚜ VOTI | of Votus (?) Vow (?) | Boleycarrigeen, Kilranelagh, County Wicklow | [15] |

| CIIC 180 | ᚛ᚁᚏᚒᚄᚉᚉᚑᚄᚋᚐᚊᚊᚔᚉᚐᚂᚔᚐᚉᚔ᚜ BRUSCCOS MAQQI CALIACỊ | "of Bruscus son of Cailech" | Emlagh East, Dingle, County Kerry | [16] |

| CIIC 193 | ᚛ᚐᚅᚋ ᚉᚑᚂᚋᚐᚅ ᚐᚔᚂᚔᚈᚆᚔᚏ᚜ ANM COLMAN AILITHIR | "[written in] the name of Colmán, the pilgrim" | Maumanorig, County Kerry | CISP MAUIG/1[17] |

| CIIC 200 | ᚛ᚋᚐᚊᚔ ᚈᚈᚐᚂ ᚋᚐᚊᚔ ᚃᚑᚏᚌᚑᚄ ᚋᚐᚊᚔ ᚋᚒᚉᚑᚔᚉᚐᚉ᚜ MAQI-TTAL MAQI VORGOS MAQI MUCOI TOICAC | Son of Dal, son of Vergosus (Fergus), son of the tribe of Toica | Coolmagort, Dunkerron North, County Kerry | CISP COOLM/4[18] |

| CIIC 300 | ᚛ᚉᚒᚅᚅᚓᚈᚐᚄ ᚋᚐᚊᚔ ᚌᚒᚉᚑᚔ ᚅᚓᚈᚐ ᚄᚓᚌᚐᚋᚑᚅᚐᚄ᚜ CUNNETAS MAQI GUC[OI] NETA-SEGAMONAS | Cunnetas, Neta-Segamonas | Old Island, Decies-without-Drum, County Waterford | CISP OLDIS/1[19] |

| CIIC 317 | ᚛ᚇᚑᚈᚓᚈᚈᚑ ᚋᚐᚊᚔ ᚋᚐᚌᚂᚐᚅᚔ᚜ DOTETTO MAQ[I MAGLANI] | Dotetto, Maglani(?) | Aghascrebagh, Upper Strabane, County Tyrone | CISP AGHAS/1[20] |

| CIIC 1082 | ᚛ᚌᚂᚐᚅᚅᚐᚅᚔ ᚋᚐᚊᚔ ᚁᚁᚏᚐᚅᚅᚐᚇ᚜ GLANNANI MAQI BBRANNAD | Ballybroman, County Kerry | CISP BALBR/1[21] | |

| CIIC 1083 | ᚛ᚉᚑᚋᚋᚐᚌᚌᚐᚌᚅᚔ ᚋᚒᚉᚑᚔ ᚄᚐᚋᚋᚅᚅ᚜ COMMAGGAGNI MU[CO]I SAMMNN | Rathkenny, Ardfert, Corkaguiney, County Kerry | CISP RTHKE/1[22] | |

| — | ᚛ᚐᚅᚋ ᚄᚔᚂᚂᚐᚅᚅ ᚋᚐᚊ ᚃᚐᚈᚈᚔᚂᚂᚑᚌᚌ᚜ [A]NM SILLANN MAQ FATTILLOGG | Ratass Church, Tralee, County Kerry | CISP RATAS/1[23] |

Wales

The orthodox inscriptions in Wales are noted for containing names of both Latin and Brythonic (or early Welsh) origin, and are mostly accompanied by a Latin inscription in the Roman alphabet (Ecclesiastical and Late Latin remained the language of writing in Wales throughout the post-Roman period). Examples of Brythonic names include (446) MAGLOCUNI ᚋᚐᚌᚂᚑᚉᚒᚅᚔ (Welsh Maelgwn) and (449) CUNOTAMI ᚉᚒᚅᚑᚈᚐᚋᚔ (Welsh cyndaf).

Wales has the distinction of the only ogham stone inscription that bears the name of an identifiable individual. The stone commemorates Vortiporius, a 6th-century king of Dyfed (originally located in Clynderwen).[24] Wales also has the only ogham inscription known to commemorate a woman. At Eglwys Cymmin (Cymmin church) in Carmarthenshire is the inscription (362) AVITORIGES INIGENA CUNIGNI ᚛ᚐᚃᚔᚈᚑᚏᚔᚌᚓᚄ ᚔᚅᚔᚌᚓᚅᚐ ᚉᚒᚅᚔᚌᚅᚔ᚜ or 'Avitoriges daughter of Cunigni'. Avitoriges is an Irish name while Cunigni is Brythonic (Welsh Cynin), reflecting the mixed heritage of the inscription makers. Wales also has several inscriptions which attempt to replicate the supplementary letter or forfeda for P (inscriptions 327 and 409).

| ID | Text | Translation / Personal names | Location | Notes |

| CIIC 423 | ᚛ᚊ[--]ᚊᚐ[--]ᚌᚈᚓ᚜ Q[--]QA[--]GTE | Son of Quegte? | Castle Villa, Brawdy, Pembrokeshire | CISP BRAW/1[25] |

| CIIC 426 | ᚛ᚅᚓᚈᚈᚐᚄᚐᚌᚏᚔ ᚋᚐᚊᚔ ᚋᚒᚉᚑᚓ ᚁᚏᚔᚐᚉᚔ᚜ NETTASAGRI MAQI MUCOE BRIACI | Nettasagri, Briaci | Bridell, Pembrokeshire | CISP BRIDL/1[26] |

| CIIC 427 | ᚛ᚋᚐᚌᚂᚔᚇᚒᚁᚐᚏ[--]ᚊᚔ᚜ MAGL[I]DUBAR [--]QI | Magl[ia], Dubr[acunas] | Caldey Island, Penally, Pembrokeshire | CISP CALDY/1[27] |

| CIIC 456 | ᚛ᚌᚓᚅᚇᚔᚂᚔ᚜ GENDILI | Gendilius | Steynton, Pembrokeshire | CISP STNTN/1[28] Latin "GENDILI" |

England, Isle of Man, Scotland

England has seven or eight ogham inscriptions, five in Cornwall and two in Devon, which are the product of early Irish settlement in the area (then the Brythonic kingdom of Dumnonia). A further inscription in Silchester in Hampshire is presumed to be the work of a lone Irish settler.

Scotland has only three orthodox inscriptions, as the rest are scholastic inscriptions made by the Picts (see below).

The Isle of Man has five inscriptions. One of these is the famous inscription at Port St. Mary (503) which reads DOVAIDONA MAQI DROATA ᚛ᚇᚑᚃᚐᚔᚇᚑᚅᚐ ᚋᚐᚊᚔ ᚇᚏᚑᚐᚈᚐ᚜ or 'Dovaidona son of the Druid'.

| ID | Text | Translation / Personal names | Location | Notes |

| CIIC 466 | ᚛ᚔᚌᚓᚅᚐᚃᚔ ᚋᚓᚋᚑᚏ᚜ IGENAVI MEMOR | Lewannick, Cornwall | CISP LWNCK/1[29] Latin text "INGENVI MEMORIA" | |

| CIIC 467 | ᚛ᚒᚂᚉᚐᚌᚅᚔ᚜ U[L]CAG[.I] / [.L]CAG[.]I | Ulcagni | Lewannick, Cornwall | CISP LWNCK/2[30] Latin text "[HI]C IACIT VLCAGNI" |

| CIIC 470 | ᚛ᚂᚐᚈᚔᚅᚔ᚜ LA[TI]NI | Worthyvale, Slaughterbridge, Minster, Cornwall | CISP WVALE/1[31] Latin text "LATINI IC IACIT FILIUS MACARI" | |

| CIIC 484 | ᚛ᚔᚒᚄᚈᚔ᚜ [I]USTI | St. Kew, Cornwall | CISP STKEW/1[32] A block of granite, Latin "IVSTI" in a cartouche | |

| CIIC 489 | ᚛ᚄᚃᚐᚊᚊᚒᚉᚔ ᚋᚐᚊᚔ ᚊᚔᚉᚔ᚜ SVAQQUCI MAQI QICI | "[The stone] of Safaqqucus, son of Qicus" | Fardel Manor, near Ivybridge, Devon | CISP FARDL/1[33] |

| CIIC 488 | ᚛ᚓᚅᚐᚁᚐᚏᚏ᚜ ENABARR | To compare with the name of the horse of Manannan Mac Lir (Enbarr)[34] | Roborough Down, Buckland Monachorum, Devon | CISP TVST3/1[35] |

| CIIC 496 | ᚛ᚓᚁᚔᚉᚐᚈᚑᚄ ᚋᚐᚊᚔ ᚋᚒᚉᚑᚔ᚜ EBICATO[S] [MAQ]I MUCO[I] [ | Silchester, Hampshire | CISP SILCH/1[36] Excavated 1893 | |

| CIIC 500 | FILIVS-ROCATI | HIC-IACIT ᚛ᚒᚁᚔᚉᚐᚈᚑᚄᚋᚐᚊᚔᚏᚑᚉᚐᚈᚑᚄ᚜ [.]b[i]catos-m[a]qi-r[o]c[a]t[o]s |

"Ammecatus son of Rocatus lies here" "[Am]bicatos son of Rocatos" | Knoc y Doonee, Kirk Andreas | CISP ANDRS/1[37] Combined Latin and Ogam |

| CIIC 501 | ᚛ᚉᚒᚅᚐᚋᚐᚌᚂᚔ ᚋᚐᚉ᚜ CUNAMAGLI MAC[ | CISP ARBRY/1[38] | ||

| CIIC 502 | ᚛ᚋᚐᚊ ᚂᚓᚑᚌ᚜ MAQ LEOG | CISP ARBRY/2[39] | ||

| CIIC 503 | ᚛ᚇᚑᚃᚐᚔᚇᚑᚅᚐ ᚋᚐᚊᚔ ᚇᚏᚑᚐᚈᚐ᚜ DOVAIDONA MAQI DROATA | "Dovaido son of the Druid." | Ballaqueeney, Port St Mary, Rushen | CISP RUSHN/1[40] |

| CIIC 504 | ᚛ᚁᚔᚃᚐᚔᚇᚑᚅᚐᚄᚋᚐᚊᚔᚋᚒᚉᚑᚔ᚜ ᚛ᚉᚒᚅᚐᚃᚐᚂᚔ᚜ BIVAIDONAS MAQI MUCOI CUNAVA[LI] | "Of Bivaidonas, son of the tribe Cunava[li]" | Ballaqueeney, Port St Mary, Rushen | CISP RUSHN/2[41] |

| CIIC 506 | ᚛ᚃᚔᚉᚒᚂᚐ ᚋᚐᚊ ᚉᚒᚌᚔᚅᚔ᚜ VICULA MAQ CUGINI | Vicula, Cugini | Gigha, Argyll | CISP GIGHA/1[42] |

| CIIC 507 | ᚛ᚉᚏᚑᚅ[-]ᚅ᚜ CRON[-][N][ | Poltaloch, Kilmartin, Argyll | CISP POLCH/1[43] Fragment, recognised in 1931 | |

| CIIC 1068 | ᚛ᚂᚒᚌᚅᚔ᚜ LUGNI | Ballavarkish, Bride | CISP BRIDE/1[44] Recognized 1911; crosses and animals, 8th or 9th century |

Scholastic inscriptions

The term 'scholastic' derives from the fact that the inscriptions are believed to have been inspired by the manuscript sources, instead of being continuations of the original monument tradition. Scholastic inscriptions typically draw a line into the stone's surface along which the letters are arranged, rather than using the stone's edge. They begin in the course of the 6th century, and continue into Old and Middle Irish, and even into Modern times. From the High Middle Ages, contemporary to the Manuscript tradition, they may contain Forfeda. The 30 or so Pictish inscriptions qualify as early Scholastic, roughly 6th to 9th century. Some Viking Age stones on Man and Shetland are in Old Norse, or at least contain Norse names.

Scotland

| ID | Text | Translation / Personal names | Location | Notes |

| CISP BRATT/1 | ᚛ᚔᚏᚐᚈᚐᚇᚇᚑᚐᚏᚓᚅᚄ᚜ IRATADDOARENS[ | Addoaren (Saint Ethernan?) | Brandsbutt, Inverurie, Aberdeenshire | CISP BRATT/1[45] Pictish(?), dated 6th to 8th century |

| CISP BREAY/1 | ᚛ᚉᚏᚏᚑᚄᚄᚉᚉ᚜ : ᚛ᚅᚐᚆᚆᚈᚃᚃᚇᚇᚐᚇᚇᚄ᚜ : ᚛ᚇᚐᚈᚈᚏᚏ᚜ : ᚛ᚐᚅᚅ[--] ᚁᚓᚅᚔᚄᚓᚄ ᚋᚓᚊᚊ ᚇᚇᚏᚑᚐᚅᚅ[--]᚜ CRRO[S]SCC : NAHHTVVDDA[DD]S : DATTRR : [A]NN[--] BEN[I]SES MEQQ DDR[O]ANN[-- | Nahhtvdd[add]s, Benises, Dr[o]ann | Bressay, Shetland | CISP BREAY/1[46] Norse or Gaelic, contains five forfeda |

| ? | ᚛ᚁᚓᚅᚇᚇᚐᚉᚈᚐᚅᚔᚋᚂ᚜ [B]ENDDACTANIM[L] | a blessing on the soul of L. | Birsay, Orkney | Excavated in 1970.[47] See Buckquoy spindle-whorl |

| ? | ᚛ᚐᚃᚒᚑᚐᚅᚅᚒᚅᚐᚑᚒᚐᚈᚓᚇᚑᚃᚓᚅᚔ᚜ AVUOANNUNAOUATEDOVENI | Avuo Anuano soothsayer of the Doveni | Auquhollie, near Stonehaven | CISP AUQUH/1[48] |

| Newton Stone | ᚐᚔᚇᚇᚐᚏᚉᚒᚅ ᚃᚓᚐᚅ ᚃᚑᚁᚏᚓᚅᚅᚔ ᚁᚐᚂᚄ[ᚁᚐᚉᚄ] ᚔᚑᚄᚄᚐᚏ AIDDARCUN FEAN FOBRENNI BA(L or K)S IOSSAR[49] | ? | Shevock toll-bar, Aberdeenshire | Contains 2(?) lines of Ogham inscriptions and an undeciphered secondary inscription[50] |

Isle of Man

- CISP KMICH/1,[51] an 11th-century combined Runic and Ogam inscription in Kirk Michael churchyard, Kirk Michael, Isle of Man

- ᚛ᚁᚂᚃᚄᚅᚆᚇᚈᚉᚊᚋᚌᚍᚎᚏᚐᚑᚒᚓᚔ᚜

- ᚛ᚋᚒᚒᚉᚑᚋᚐᚂᚂᚐᚃᚔᚒᚐᚋᚒᚂᚂᚌᚒᚉ᚜

- ᛘᛅᛚ᛬ᛚᚢᛘᚴᚢᚿ᛬ᚱᛅᛁᛋᛏᛁ᛬ᚴᚱᚢᛋ᛬ᚦᛁᚾᛅ᛬ᛁᚠᛏᛁᚱ᛬ᛘᛅᛚ᛬ᛘᚢᚱᚢ᛬ᚠᚢᛋᛏᚱᛅ᛬ᛋᛁᚾᛁ᛬ᛏᚭᛏᛁᚱᛏᚢᚠᚴᛅᛚᛋ᛬ᚴᚭᚾᛅ᛬ᛁᛋ᛬ᛅᚦᛁᛋᛚ᛬ᛅᛏᛁ᛭

- ᛒᛁᛏᚱᛅᛁᛋ᛬ᛚᛅᛁᚠᛅ᛬ᚠᚢᛋᛏᚱᛅ᛬ᚴᚢᚦᛅᚾ᛬ᚦᛅᚾ᛬ᛋᚭᚾ᛬ᛁᛚᛅᚾ᛭

- Transcription:

- blfsnhdtcqmgngzraouei

- MUUCOMAL LAFIUA MULLGUC

- MAL : LUMKUN : RAISTI : KRUS : ÞINA : IFTIR : MAL : MURU : FUSTRA : SINI : TOTIRTUFKALS : KONA : IS : AÞISL : ATI+

[B]ITRA : IS : LAIFA : FUSTRA : KUÞAN : ÞAN : SON : ILAN +- Translation:

- An ogham abecedarium (the whole ogham alphabet)

- "Mucomael grandson/descendant of O'Maelguc"

- "Mal Lumkun set up this cross in memory of Mal Mury her foster-son, daughter of Dufgal, the wife whom Athisl married,"

- "Better it is to leave a good foster son than a bad son"

- (The runic part is in Norse.)

- ᚁᚐᚉ ᚑᚉᚑᚔᚉᚐᚈᚔᚐᚂᚂ or possibly ᚐ ᚋᚐᚊᚔᚋᚒᚉᚑᚔᚉᚐᚈᚔᚐᚂᚂ

- ...BAC......OCOICATIALL possibly 'A thong (group) of fifty warriors'

- An ogham inscription in Old Irish discovered at the Speke Farm keeill (chapel) by the seventh fairway of the Mount Murray golf course five miles southwest of Douglas by a Time Team excavation.

- Has been defined as an 11th - 12th century inscription on stylistic grounds (use of bind ogham)[52]

- However there has been at least one proposed date of 6th - 8th century from the association of a 6-7th century grave nearby, with the possibility of the more familiar variant reading '..A...MACI MUCOI CATIALL[I]' '..., son of the tribe of Catiall[i].'[53]

Ireland

- A 19th-century ogham inscription from Ahenny, Co. Tipperary (Raftery 1969)

- Beneath this sepulchral tomb lie the remains of Mary Dempsey who departed this life January the 4th 1802 aged 17 years

- ᚛ᚃᚐᚐᚅᚂᚔᚌᚄᚑᚅᚐᚂᚒᚐᚈᚐᚋᚐᚏᚔᚅᚔᚇᚆᚔᚋᚒᚄᚐ᚜ ᚛ᚑᚋᚁᚐᚂᚂᚔᚅᚐᚌᚉᚏᚐᚅᚔᚁᚆ᚜

- fa an lig so na lu ata mari ni dhimusa / o mballi na gcranibh

- "Beneath this stone lieth Mári Ní Dhíomasaigh from Ballycranna"

Manuscript tradition

- Latin text written in ogham, in the Annals of Inisfallen of 1193 (ms. Rawlinson B. 503, 40c)

- ᚛ᚅᚒᚋᚒᚄ ᚆᚑᚅᚑᚏᚐᚈᚒᚏ ᚄᚔᚅᚓ᚜ ᚛ᚅᚒᚋᚑ ᚅᚒᚂᚂᚒᚄ ᚐᚋᚐᚈᚒᚏ᚜

- nummus honoratur sine / nummo nullus amatur

- This is a hexameter line with internal rhyme at the caesura, to be scanned as follows: nūmmus honōrātur || sine nūmmō nullus amātur.

- "Money is honoured, without money nobody is loved"

- Fictional inscription: a Middle Irish saga text recorded in the Book of Leinster (LL 66 AB) mentions the following ogham inscription:

- ᚛ᚌᚔᚚ ᚓ ᚈᚔᚄᚓᚇ ᚔᚅ ᚃᚐᚔᚇᚉᚆᚓ᚜ ᚛ᚇᚘᚐ ᚋᚁᚐ ᚌᚐᚄᚉᚓᚇᚐᚉᚆ᚜

- ᚛ᚌᚓᚔᚄ ᚃᚐᚔᚏ ᚐᚏ ᚈᚆᚓᚉᚆᚈ ᚇᚔᚅᚇ ᚃᚐᚔᚇᚉᚆᚔ᚜

- ᚛ᚉᚓᚅ ᚉᚆᚑᚋᚏᚐᚉ ᚅᚑᚓᚅᚃᚆᚔᚏ ᚇᚑ ᚃᚆᚒᚐᚉᚏᚐ᚜

- Gip e tised in faidche, dia m-ba gascedach, geis fair ar thecht dind faidchi cen chomrac n-oenfhir do fhuacra.

- "Whoever comes to this meadow, if he be armed, he is forbidden to leave the meadow, without requesting single combat."

Literature

- Brash, R. R., The Ogam Inscribed Monuments of the Gaedhil in the British Isles, London (1879).

- J. Higgitt, K. Forsyth, D. Parsons (eds.), Roman, Runes and Ogham. Medieval Inscriptions in the Insular World and on the Continent, Donington: Shaun Tyas (2001).

- Jackson, K.H., Notes on the Ogam inscriptions of southern Britain, in C. Fox, B. Dickins (eds.) The Early Cultures of North-West Europe. Cambridge: 197—213 (1950).

- Macalister, Robert A.S. The Secret Languages of Ireland, pp27 – 36, Cambridge University Press, 1937

- Macalister, R. A. S., Corpus Inscriptionum Insularum Celticarum Vol. I., Dublin: Stationery Office (1945).

- Macalister, R. A. S., Corpus Inscriptionum Insularum Celticarum' Vol. II., Dublin: Stationery Office (1949).

- McManus, D, A Guide to Ogam, An Sagart, Maynooth, Co. Kildare (1991)

- MacNeill, Eoin. Archaisms in the Ogham Inscriptions, 'Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy' 39, pp 33–53, Dublin

- Ziegler, S., Die Sprache der altirischen Ogam-Inschriften, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht (1994).

References

- ↑ "INCHA/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "TITUS-Ogamica 002". Titus.fkidg1.uni-frankfurt.de. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ↑ "CLOOM/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "ISLAN/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "KILMA/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "RUSHE/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "TULLA/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ ᚖ also [θ]: Macalister, Introduction, p. 5, and CIIC 7, pp. 9-10

- ↑ "CORRO/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "DOOGH/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "AGHAL/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "BREAS/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "Ogham in 3D - Ballyboodan / 38. Ballyboodan". Ogham.celt.dias.ie. 21 July 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ↑ "Titus Database Ogamica : CIIC No. 047". Titus.fkidgl.uni-frankfurt.de. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ↑ Marsh, Richard. "Crossoona Rath | BALTINGLASS | Places". County Wicklow Heritage. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ↑ "TITUS-Ogamica 180". titus.uni-frankfurt.de.

- ↑ "MAUIG/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "COOLM/4". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "OLDIS/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "AGHAS/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "BALBR/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "RTHKE/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ Discovered in 1975. Thomas Fanning and Donncha Ó Corráin, "An Ogham stone and cross-slab from Ratass Church, Tralee", JKAHS 10 (1977), pp. 14–18.

- ↑ Davies, John (2008). The Welsh Academy Encyclopedia of Wales. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-7083-1953-6.

- ↑ "BRAW/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "BRIDL/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "CALDY/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "STNTN/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "LWNCK/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "LWNCK/2". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "WVALE/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "STKEW/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "FARDL/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ J. A. MacCulloch, The Religion of the Ancient Celts

- ↑ "TVST3/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "SILCH/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "ANDRS/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "ARBRY/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "ARBRY/2". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "RUSHN/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "RUSHN/2". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "GIGHA/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "POLCH/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "BRIDE/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "BRATT/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ "BREAY/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ Forsyth, Katherine (1995). "The ogham-inscribed spindle-whorl from Buckquoy: evidence for the Irish language in pre-Viking Orkney?". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland. 125: 677–696. ISSN 0081-1564.

- ↑ "AUQUH/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ Brash, Richard Rolt (10 March 1873). "ON THE OGHAM INSCRIPTION OF THE NEWTON PILLAR-STONE" (PDF). Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland: 139.

- ↑ "Site Record for Newton House, The Newton Stone Newton in the Garioch". RCAHMS. Retrieved 3 March 2013.

- ↑ "KMICH/1". Celtic Inscribed Stones Project. University College London.

- ↑ Wessex Archaeology, Speke Keeill, Mount Murray Hotel, Isle of Man, Archaeological Evaluation and Assessment of Results (Ref: 62511.01 July 2007)

- ↑ "BabelStone Blog : A Throng of Fifty Warriors Routed by a Single Scholar : An Exercise in Ogham Decipherment". www.babelstone.co.uk.