| Bussa's Rebellion | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of North American slave revolts | |||||||

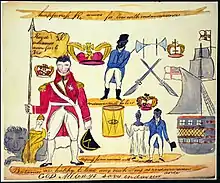

Sketch of a flag used by the Bussa rebels including the slogan "Happiness Remains for Ever with endeavourance... Britannia are happy to lead any such Sons as endeavourance and God Always saves endeavour" [sic] | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Rebelling Slaves | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Bussa † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~400 (actively fighting)[2] ~5,000 (total rebelling) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Part of a series on |

| North American slave revolts |

|---|

|

Bussa's rebellion (14–16 April 1816) was the largest slave revolt in Barbadian history. The rebellion takes its name from the African-born slave, Bussa, who led the rebellion. The rebellion, which was eventually defeated by the colonial militia, was the first of three mass slave rebellions in the British West Indies that shook public faith in slavery in the years leading up to the abolition of slavery in the British Empire and emancipation of former slaves. It was followed by the Demerara rebellion of 1823 and by the Baptist War in Jamaica in 1831–1832; these are often referred to as the "late slave rebellions".

Bussa

Bussa (/ˈbʌsə/) was born a free man in West Africa of possible Igbo descent and was captured by African merchants, sold to European slave traders and transported to Barbados in the late 18th century as a slave, where under the Barbados Slave Code slavery had been legal since 1661.[3] Not much is known about him and there are no earlier records of him, and virtually no biographical information about Bussa is available. Records show a slave named "Bussa" worked as a ranger (a head officer among the slaves) on "Bayley's Plantation" in the parish of Saint Philip around the time of the rebellion.[1] This position would have given Bussa more freedom of movement than the average slave and would have made it easier for him to plan and coordinate the rebellion.

Revolt

The revolts arose at a time when the British Parliament was working on schemes to ameliorate the conditions of slaves in the Caribbean. Preparation for this rebellion began soon after the House of Assembly discussed and rejected the Imperial Registry Bill in November 1815, which would have registered West Indian slaves. Historians believe that slaves interpreted some of the parliamentary proposals as preparatory to emancipation, and took action when emancipation did not take place.[2]

Among Bussa's collaborators were Joseph Pitt Washington Franklin (a free man), John and Nanny Grigg, a senior domestic slave, and Jackey on Simmons' Plantation, as well as other slaves, drivers and artisans. Jackey was a Creole driver who was an important figure. The planning was undertaken at a number of sugar estates, including Bailey's plantation, where it began. By February 1816, Bussa was an African driver, one of the few in his position.[2] He and his collaborators decided to start the revolt on 14 April, Easter Sunday.

Bussa, King Wiltshire, Dick Bailey and Johnny led the slaves into battle at Bailey's Plantation on Tuesday, 16 April. He commanded some 400 rebels, men and women, most of whom were believed to be Creole, born in the islands. He was killed in battle, his forces continued the fight until they were defeated by superior firepower of the colonial militia. The rebellion failed but its influence was significant to the future of Barbados.

Legacy

- Bussa remains a popular figure in Barbados.

- In 1985, 169 years after his rebellion, the Emancipation Statue, created by Karl Broodhagen, was unveiled in Haggatt Hall, in the parish of St Michael. Many Barbadians attributed the statue to Bussa and nicknamed it "Bussa's Statue".[4]

- 1998, the Parliament of Barbados named Bussa as one of the eleven National Heroes of Barbados.[5]

References

- 1 2 The National Archives. "Bussa's rebellion". Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- 1 2 3 "The Emancipation Wars", National Library of Jamaica

- ↑ Williams, Emily Allen (2004). The Critical Response to Kamau Brathwaite. Praeger Publishers. p. 235. ISBN 0-275-97957-1.

- ↑ "Emancipation Statue". Barbados.org. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- ↑ "Parliament's History". BarbadosParliament.com. Parliament of Barbados. 2009. Archived from the original on 23 May 2007. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

Further reading

- Beckles, Hilary. "A History of Barbados: From Amerindian Settlement to Caribbean Single Market". Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Beckles, Hilary. Black Rebellion in Barbados. Bridgetown, Barbados: Antilles Publications, 1984. [detailed account of the rebellion]

- Craton, Michael. Testing the Chains: Resistance to Slavery in the British West Indies, Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1982. [detailed account of the rebellion]

- Rodriguez, Junius P., ed. Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion. Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2006.

External links

- Bussa profile, Itzcaribbean

- Bussa's Rebellion: How and Why did the Enslaved Africans of Barbados rebel in 1816, National Archives (UK)