| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Florina, Edessa, Kastoria, Thessaloniki, Serres, Kilkis[1] | |

| 50,000–250,000 (est.)[2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9] | |

| descendants of the 92,000–120,000 (est.) refugees from Greece (1913–1950)[10][11][12] | |

| 81,745 (2006 census) – 90,000 (est.) descendants of migrants from the region of Macedonia[13][14] | |

| 50,000 – 70,000 (est., incl. descendants)[15] | |

| 26,000 (est.)[16] | |

| 30,000 (est.)[16][17] | |

Vojvodina (Banat) | 7,500 (est.) |

| Languages | |

| Macedonian, Bulgarian, Greek | |

| Religion | |

| Greek Orthodox Church, Islam | |

Slavic speakers are a minority population in the northern Greek region of Macedonia, who are mostly concentrated in certain parts of the peripheries of West and Central Macedonia, adjacent to the territory of the state of North Macedonia. Their dialects are called today "Slavic" in Greece, while generally they are considered Macedonian. Some members have formed their own emigrant communities in neighbouring countries, as well as further abroad.

History

Middle Ages and Ottoman rule

The Slavs took advantage of the desolation left by the nomadic tribes and in the 6th century settled the Balkan Peninsula. Aided by the Avars and the Bulgars, the Slavic tribes started in the 6th century a gradual invasion into the Byzantine lands. They invaded Macedonia and reached as far south as Thessaly and the Peloponnese, settling in isolated regions that were called by the Byzantines Sclavinias, until they were gradually pacified. At the beginning of the 9th century, the Slavic Bulgarian Empire conquered Northern Byzantine lands, including most of Macedonia. Those regions remained under Bulgarian rule for two centuries, until the conquest of Bulgaria by the Byzantine Emperor of the Macedonian dynasty Basil II in 1018. In the 13th and the 14th century, Macedonia was contested by the Byzantine Empire, the Latin Empire, Bulgaria and Serbia but the frequent shift of borders did not result in any major population changes. In 1338, the geographical area of Macedonia was conquered by the Serbian Empire, but after the Battle of Maritsa in 1371 most of the Macedonian Serbian lords would accept supreme Ottoman rule.

During the Middle Ages Slavs in South Macedonia were mostly defined as Bulgarians,[18][19] and this continued also during 16th and 17th centuries by Ottoman historians and travellers like Hoca Sadeddin Efendi, Mustafa Selaniki, Hadji Khalfa and Evliya Çelebi. Nevertheless, most of the Slavic speakers had not formed a national identity in modern sense and were instead identified through their religious affiliations.

Some Slavic speakers also converted to Islam. This conversion appears to have been a gradual and voluntary process. Economic and social gain was an incentive to become a Muslim. Muslims also enjoyed some legal privileges. Nevertheless, the rise of European nationalism in the 18th century led to the expansion of the Hellenic idea in Macedonia and under the influence of the Greek schools and the Patriarchate of Constantinople, and part from the urban Christian population of Slavic origin started to view itself more as Greek. In the Bulgarian Archbishopric of Ohrid the Slavonic liturgy was preserved on the lower levels until its abolition in 1767. This led to the first literary work in vernacular modern Bulgarian, History of Slav-Bulgarians in 1762. Its author was a Macedonia-born monk Paisius of Hilendar, who wrote it in the Bulgarian Orthodox Zograf Monastery, on Mount Athos. Nevertheless, it took almost a century for the Bulgarian idea to regain ascendancy in the region. Paisius was the first ardent call for a national awakening and urged his compatriots to throw off the subjugation to the Greek language and culture. The example of Paisius was followed also by other Bulgarian nationalists in 18th century Macedonia.

The Macedonian Bulgarians took active part in the long struggle for independent Bulgarian Patriarchate and Bulgarian schools during the 19th century. The foundation of the Bulgarian Exarchate (1870) aimed specifically at differentiating the Bulgarian from the Greek population on an ethnic and linguistic basis, hence providing the conditions for the open assertion of a Bulgarian national identity.[20] On the other hand, the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (IMARO) was founded in 1893 in Ottoman Thessaloniki by several Bulgarian Exarchate teachers and professionals who sought to create a militant movement dedicated to the autonomy of Macedonia and Thrace within the Ottoman Empire. Many Bulgarian exarchists participated in the Ilinden Uprising in 1903 with hope of liberation from the Porte. In 1883 the Kastoria region consisted of 60,000 people, all Christian, of which 4/9 were Slavophone Greeks and the rest 5/9 were Grecophone Greeks, Albanophone Greeks and Aromanians.[21]

French ethnographic map of the Balkans by Ami Boue, 1847.

French ethnographic map of the Balkans by Ami Boue, 1847. The nationalities of southeastern Europe according to Pallas Nagy Lexikona, 1897.

The nationalities of southeastern Europe according to Pallas Nagy Lexikona, 1897. The regions of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by ethnic Bulgarians in 1912, according to the Bulgarian point of view.

The regions of the Balkan Peninsula inhabited by ethnic Bulgarians in 1912, according to the Bulgarian point of view. Greek ethnographic map from 1918, showing the Macedonian Slavs as a separate people.

Greek ethnographic map from 1918, showing the Macedonian Slavs as a separate people.

Bulgarian Exarchate seal of the Voden (Edessa) municipality, 1870.

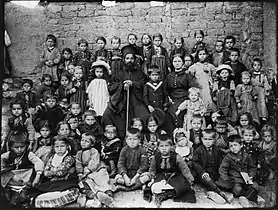

Bulgarian Exarchate seal of the Voden (Edessa) municipality, 1870. Pupils of the Greek school of Zoupanishta, near Kastoria.

Pupils of the Greek school of Zoupanishta, near Kastoria.

The title page of the Konikovo Gospel, printed in 1852.

The title page of the Konikovo Gospel, printed in 1852.

From 1900 onwards, the danger of Bulgarian control had upset the Greeks. The Bishop of Kastoria, Germanos Karavangelis, realised that it was time to act in a more efficient way and started organising Greek opposition. Germanos animated the Greek population against the IMORO and formed committees to promote the Greek interests. Taking advantage of the internal political and personal disputes in IMORO, Karavangelis succeeded to organize guerrilla groups. Fierce conflicts between the Greeks and Bulgarians started in the area of Kastoria, in the Giannitsa Lake and elsewhere; both parties committed cruel crimes. Both guerrilla groups had also to confront the Turkish army. These conflicts ended after the revolution of "Young Turks" in 1908, as they promised to respect all ethnicities and religions and generally to provide a constitution.

Balkan Wars and World War I

During the Balkan Wars, many atrocities were committed by Turks, Bulgarians and Greeks in the war over Macedonia. After the Balkan Wars ended in 1913, Greece took control of southern Macedonia and began an official policy of forced assimilation which included the settlement of Greeks from other provinces into southern Macedonia, as well as the linguistic and cultural Hellenization of Slav speakers.[22] which continued even after World War I.[23] The Greeks expelled Exarchist churchmen and teachers and closed Bulgarian schools and churches. The Bulgarian language (including the Macedonian dialects) was prohibited, and its surreptitious use, whenever detected, was ridiculed or punished.[24]

Bulgaria's entry into World War I on the side of the Central Powers signified a dramatic shift in the way European public opinion viewed the Bulgarian population of Macedonia. The ultimate victory of the Allies in 1918 led to the victory of the vision of the Slavic population of Macedonia as an amorphous mass, without a developed national consciousness. Within Greece, the ejection of the Bulgarian church, the closure of Bulgarian schools, and the banning of publication in Bulgarian language, together with the expulsion or flight to Bulgaria of a large proportion of the Macedonian Bulgarian intelligentsia, served as the prelude to campaigns of forcible cultural and linguistic assimilation. The remaining Macedonian Bulgarians were classified as "Slavophones".[25] After the Ilinden Uprising, the Balkan Wars and especially after the First World War more than 100,000 Bulgarians from Greek Macedonia moved to Bulgaria.

There was agreement in 1919 between Bulgaria and Greece which provided opportunities to expatriate the Bulgarians from Greece.[26] Until the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922) and the Population exchange between Greece and Turkey in 1923 there were also some Pomak communities in the region.[27]

Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO)

During the Balkan Wars IMRO members joined the Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps and fought with the Bulgarian Army. Others with their bands assisted the Bulgarian army with its advance and still others penetrated as far as the region of Kastoria, southwestern Macedonia. In the Second Balkan War IMRO bands fought the Greeks behind the front lines but were subsequently routed and driven out. The result of the Balkan Wars was that the Macedonian region was partitioned between Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia. IMARO maintained its existence in Bulgaria, where it played a role in politics by playing upon Bulgarian irredentism and urging a renewed war. During the First World War in Macedonia (1915–1918) the organization supported Bulgarian army and joined to Bulgarian war-time authorities. Bulgarian army, supported by the organization's forces, was successful in the first stages of this conflict, came into positions on the line of the pre-war Greek-Serbian border.

The Bulgarian advance into Greek held Eastern Macedonia, precipitated internal Greek crisis. The government ordered its troops in the area not to resist, and most of the Corps was forced to surrender. However the post-war Treaty of Neuilly again denied Bulgaria what it felt was its share of Macedonia. From 1913 to 1926 there were large-scale changes in the population structure due to ethnic migrations. During and after the Balkan Wars about 15,000 Slavs left the new Greek territories for Bulgaria but more significant was the Greek–Bulgarian convention 1919 in which some 72,000 Slavs-speakers left Greece for Bulgaria, mostly from Eastern Macedonia, which from then remained almost Slav free. IMRO began sending armed bands into Greek Macedonia to assassinate officials. In the 1920s in the region of Greek Macedonia 24 chetas and 10 local reconnaissance detachments were active. Many locals were repressed by the Greek authorities on suspicions of contacts with the revolutionary movement. In this period the combined Macedonian-Adrianopolitan revolutionary movement separated into Internal Thracian Revolutionary Organization and Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization. ITRO was a revolutionary organization active in the Greek regions of Thrace and Eastern Macedonia to the river Strymon. The reason for the establishment of ITRO was the transfer of the region from Bulgaria to Greece in May 1920.

| Part of a series on |

| Bulgarians Българи |

|---|

|

| Culture |

| By country |

| Subgroups |

| Religion |

| Language |

| Other |

|

At the end of 1922, the Greek government started to expel large numbers of Thracian Bulgarians into Bulgaria and the activity of ITRO grew into an open rebellion. Meanwhile, the left-wing did form the new organisation called IMRO (United) in 1925 in Vienna. However, it did not have real popular support and remained based abroad with, closely linked to the Comintern and the Balkan Communist Federation. IMRO's and ITRO's constant fratricidal killings and assassinations abroad provoked some within Bulgarian military after the coup of 19 May 1934 to take control and break the power of the organizations, which had come to be seen as a gangster organizations inside Bulgaria and a band of assassins outside it.

Interwar period

The Tarlis and Petrich incidents triggered heavy protests in Bulgaria and international outcry against Greece. The Common Greco-Bulgarian committee for emigration investigated the incident and presented its conclusions to League of Nations in Geneva. As a result, a bilateral Bulgarian-Greek agreement was signed in Geneva on September 29, 1925, known as Politis-Kalfov protocol after the demand of the League of Nations, recognizing Greek Slavophones as Bulgarians and guaranteeing their protection. Next month a Slavic language primer textbook in Latin known as Abecedar published by the Greek ministry for education, was introduced to Greek schools of Aegean Macedonia. On February 2, 1925, the Greek parliament, under pressure from Serbia, rejected ratification of the 1913 Greek-Serbian Coalition Treaty. Agreement lasted 9 months until June 10, 1925, when League of Nations annulled it.

During the 1920s the Comintern developed a new policy for the Balkans, about collaboration between the communists and the Macedonian movement. The idea for a new unified organization was supported by the Soviet Union, which saw a chance for using this well developed revolutionary movement to spread revolution in the Balkans. In the so-called May Manifesto of 6 May 1924, for first time the objectives of the unified Slav Macedonian liberation movement were presented: "independence and unification of partitioned Macedonia, fighting all the neighbouring Balkan monarchies, forming a Balkan Communist Federation". In 1934 the Comintern issued also a special resolution about the recognition of the Slav Macedonian ethnicity.[28] This decision was supported by the Greek Communist Party.

The 1928 census recorded 81,844 Slavo-Macedonian speakers or 1.3% of the population of Greece, distinct from 16,755 Bulgarian speakers.[29] Contemporary unofficial Greek reports state that there were 200,000 "Bulgarian"-speaking inhabitants of Macedonia, of whom 90,000 lack Greek national identity.[29] The bulk of the Slavo-Macedonian minority was concentrated in West Macedonia.[29] The census reported that there were 38,562 of them in the nome (district) of Florina or 31% of the total population and 19,537 in the nome of Edessa (Pella) or 20% of the population.[29] According to the prefect of Florina, in 1930 there were 76,370 (61%), of whom 61,950 (or 49% of the population) lacked Greek national identity.

The situation for Slavic speakers became unbearable when the Metaxas regime took power in 1936.[16] Metaxas was firmly opposed to the irredentist factions of the Slavophones of northern Greece mainly in Macedonia and Thrace, some of whom underwent political persecution due to advocacy of irredentism with regard to neighboring countries. Place names and surnames were officially Hellenized and the native Slavic dialects were banned even in personal use.[16] It was during this time that many Slavic speakers fled their homes and emigrated to the United States, Canada and Australia. The name changes took place according to the Greek language.

Ohrana and the Bulgarian annexation during WWII

Ohrana were armed detachments organized by the Bulgarian army, composed of pro-Bulgarian oriented part of the Slavic population in occupied Greek Macedonia during World War II, led by Bulgarian officers.[30] In 1941 Greek Macedonia was occupied by German, Italian and Bulgarian troops. The Bulgarian troops occupied the Eastern Macedonia and Western Thrace. The Bulgarian policy was to win the loyalty of the Slav inhabitants and to instill them a Bulgarian national identity. Indeed, many of these people did greet the Bulgarians as liberators, particularly in eastern and central Macedonia, however, this campaign was less successful in German-occupied western Macedonia.[31] At the beginning of the occupation in Greece most of the Slavic speakers in the area felt themselves to be Bulgarians.[32] Only a small part espoused a pro-Hellenic feelings.

The Bulgarian occupying forces began a campaign of exterminating Greeks from Macedonia. The Bulgarians were supported in this ethnic cleansing by the Slavic minority in Macedonia. In the city of Drama in May 1941, over 15,000 Greeks were killed. By the end of 1941, over 100,000 Greeks were expelled from this region.[33]

Unlike Germany and Italy, Bulgaria officially annexed the occupied territories, which had long been a target of Bulgarian irridentism.[34] A massive campaign of "Bulgarisation" was launched, which saw all Greek officials deported. This campaign was successful especially in Eastern and later in Central Macedonia, when Bulgarians entered the area in 1943, after Italian withdrawal from Greece. All Slav-speakers there were regarded as Bulgarians and not so effective in German-occupied Western Macedonia. A ban was placed on the use of the Greek language, the names of towns and places changed to the forms traditional in Bulgarian. In addition, the Bulgarian government tried to alter the ethnic composition of the region, by expropriating land and houses from Greeks in favour of Bulgarian settlers. The same year, the German High Command approved the foundation of a Bulgarian military club in Thessaloníki. The Bulgarians organized supplying of food and provisions for the Slavic population in Central and Western Macedonia, aiming to gain the local population that was in the German and Italian occupied zones. The Bulgarian clubs soon started to gain support among parts of the population. Many Communist political prisoners were released with the intercession of Bulgarian Club in Thessaloniki, which had made representations to the German occupation authorities. They all declared Bulgarian ethnicity.[35][36]

In 1942, the Bulgarian club asked assistance from the High command in organizing armed units among the Slavic-speaking population in northern Greece. For this purpose, the Bulgarian army, under the approval of the German forces in the Balkans sent a handful of officers from the Bulgarian army, to the zones occupied by the Italian and German troops to be attached to the German occupying forces as "liaison officers". All the Bulgarian officers brought into service were locally born Macedonians who had immigrated to Bulgaria with their families during the 1920s and 1930s as part of the Greek-Bulgarian Treaty of Neuilly which saw 90,000 Bulgarians migrating to Bulgaria from Greece. These officers were given the objective to form armed Bulgarian militias. Bulgaria was interested in acquiring the zones under Italian and German occupation and hopped to sway the allegiance of the 80,000 Slavs who lived there at the time.[30] The appearance of Greek partisans in those areas persuaded the Italians to allow the formation of these collaborationist detachments.[30] Following the defeat of the Axis powers and the evacuation of the Nazi occupation forces many members of the Ohrana joined the SNOF where they could still pursue their goal of secession. The advance of the Red Army into Bulgaria in September 1944, the withdrawal of the German armed forces from Greece in October, meant that the Bulgarian Army had to withdraw from Greek Macedonia and Thrace. There was a rapprochement between the Greek Communist Party and the Ohrana collaborationist units.[37]

Further collaboration between the Bulgarian-controlled Ohrana and the EAM controlled SNOF followed when it was agreed that Greek Macedonia would be allowed to secede.[38][39] Finally it is estimated that entire Ohrana units had joined the SNOF which began to press the ELAS leadership to allow it autonomous action in Greek Macedonia.[40]

There had been also a larger flow of refugees into Bulgaria as the Bulgarian Army pulled out of the Drama-Serres region in late 1944. A large proportion of Bulgarians and Slavic speakers emigrated there. In 1944 the declarations of Bulgarian nationality were estimated by the Greek authorities, on the basis of monthly returns, to have reached 16,000 in the districts of German-occupied Greek Macedonia,[41] but according to British sources, declarations of Bulgarian nationality throughout Western Macedonia reached 23,000.[42] In the beginning of the Bulgarian occupation in 1941 there were 38,611 declarations of Bulgarian identity in Eastern Macedonia. Then the ethnic composition of the Serres region consisted of 67 963 Greeks, 11 000 Bulgarians and 1237 others; in Sidirokastro region- 22 295 Greeks, 10 820 Bulgarians and 685 others; Drama region- 11 068 Bulgarians, 117 395 Greeks and others; Nea Zichni region – 4710 Bulgarians, 28 724 Greeks and others; Kavala region – 59 433 Greeks, 1000 Bulgarians and 3986 others; Thasos- 21 270 and 3 Bulgarians; Eleftheroupoli region- 36 822 Greeks, 10 Bulgarians and 301 others.[43] At another census in 1943 the Bulgarian population had increased by less than 50,000 and not larger was the decrease of the Greek population.[44]

Greek Civil War

During the beginning of the Second World War, Greek Slavic-speaking citizens fought within the Greek army until the country was overrun in 1941. The Greek communists had already been influenced by the Comintern and it was the only political party in Greece to recognize Macedonian national identity.[45] As result many Slavic speakers joined the Communist Party of Greece (KKE) and participated in partisan activities. The KKE expressed its intent to "fight for the national self-determination of the repressed Macedonians".[46]

In 1943, the Slavic-Macedonian National Liberation Front (SNOF) was set up by ethnic Macedonian members of the KKE. The main aim of the SNOF was to obtain the entire support of the local population and to mobilize it, through SNOF, for the aims of the National Liberation Front (EAM).[47] Another major aim was to fight against the Bulgarian organisation Ohrana and Bulgarian authorities.[48]

During this time, the ethnic Macedonians in Greece were permitted to publish newspapers in Macedonian and run schools.[49] In late 1944 after the German and Bulgarian withdrawal from Greece, the Josip Broz Tito's Partisans movement hardly concealed its intention of expanding. It was from this period that Slav-speakers in Greece who had previously referred to themselves as "Bulgarians" increasingly began to identify as "Macedonians".[50]

By 1945 World War II had ended and Greece was in open civil war. It has been estimated that after the end of the Second World War over 20,000 people fled from Greece to Bulgaria. To an extent the collaboration of the peasants with the Germans, Italians, Bulgarians or ELAS was determined by the geopolitical position of each village. Depending upon whether their village was vulnerable to attack by the Greek communist guerrillas or the occupation forces, the peasants would opt to support the side in relation to which they were most vulnerable. In both cases, the attempt was to promise "freedom" (autonomy or independence) to the formerly persecuted Slavic minority as a means of gaining its support.[51]

National Liberation Front

| Part of a series on |

| Macedonians |

|---|

|

| By region or country |

| Macedonia (region) |

| Diaspora |

|

|

|

|

|

Subgroups and related groups |

|

|

| Culture |

|

|

| Religion |

| Other topics |

The National Liberation Front (NOF) was organized by the political and military groups of the Slavic minority in Greece, active from 1945 to 1949. The interbellum was the time when part of them came to the conclusion that they are Macedonians. Greek hostility to the Slavic minority produced tensions that rose to separatism. After the recognition in 1934 from the Comintern of the Macedonian ethnicity, the Greek communists also recognized Macedonian national identity. That separatism was reinforced by Communist Yugoslavia's support, since Yugoslavia's new authorities after 1944 encouraged the growth of Macedonian national consciousness.

Following World War II, the population of Yugoslav Macedonia did begin to feel themselves to be Macedonian, assisted and pushed by a government policy.[52] Communist Bulgaria also began a policy of making Macedonia connecting link for the establishment of new Balkan Federative Republic and stimulating in Bulgarian Macedonia a development of distinct Slav Macedonian consciousness.[53] However, differences soon emerged between Yugoslavia and Bulgaria concerning the national character of the Macedonian Slavs – whereas Bulgarians considered them to be an offshoot of the Bulgarians,[54] Yugoslavia regarded them as an independent nation which had nothing to do whatsoever with the Bulgarians.[55] Thus the initial tolerance for the Macedonization of Pirin Macedonia gradually grew into outright alarm.

At first, the NOF organized meetings, street and factory protests and published illegal underground newspapers. Soon after its founding, members began forming armed partisan detachments. In 1945, 12 such groups were formed in Kastoria, 7 in Florina, and 11 in Edessa and the Gianitsa region.[56] Many Aromanians also joined the Macedonians in NOF, especially in the Kastoria region. The NOF merged with the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE) which was the main armed unit supporting the Communist Party.

Owing to the KKE's equal treatment of ethnic Macedonians and Greeks, many ethnic Macedonians enlisted as volunteers in the DSE (60% of the DSE was composed of Slavic Macedonians).[57] It was during this time that books written in the Macedonian dialect (the official language was in process of codifying) were published and Macedonians cultural organizations theatres were opened.[58]

According to information announced by Paskal Mitrovski on the I plenum of NOF in August 1948, about 85% of the Slavic-speaking population in Greek Macedonia had an ethnic Macedonian self-identity. It has been estimated that out of DSE's 20,000 fighters, 14,000 were Slavic Macedonians from Greek Macedonia.[58][59] Given their important role in the battle,[60] the KKE changed its policy towards them. At the fifth Plenum of KKE on January 31, 1949, a resolution was passed declaring that after KKE's victory, the Slavic Macedonians would find their national restoration as they wish.[61]

Refugee children

The DSE was slowly driven back and eventually defeated. Thousands of Slavic speakers were expelled and fled to the newly established Socialist Republic of Macedonia, while thousands more children took refuge in other Eastern Bloc countries.[58] They are known as Децата бегалци/Decata begalci. Many of them made their way to the US, Canada and Australia. Other estimates claim that 5,000 were sent to Romania, 3,000 to Czechoslovakia, 2,500 to Bulgaria, Poland and Hungary and a further 700 to East Germany. There are also estimations that 52,000 – 72,000 people in total (incl. Greeks) were evacuated from Greece.[58] However a 1951 document from the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia states the total number of ethnic Macedonian and Greeks arriving from Greece between the years 1941–1951 is 28,595.

From 1941 until 1944 500 found refuge in the People's Republic of Macedonia, in 1944 4,000 people, in 1945 5,000, in 1946 8,000, in 1947 6,000, in 1948 3,000, in 1949 2,000, in 1950 80, and in 1951 15 people. About 4,000 left Yugoslavia and moved to other Socialist countries (and very few went also to western countries). So in 1951 in Yugoslavia were 24,595 refugees from Greek Macedonia. 19,000 lived in Yugoslav Macedonia, 4,000 in Serbia (mainly in Gakovo-Krusevlje) and 1595 in other Yugoslav republics.[62]

This data is confirmed by the KKE, which claims that the total number of political refugees from Greece (incl. Greeks) was 55,881.[63]

Post-war period

Since the end of the Greek Civil War many ethnic Macedonians have attempted to return to their homes in Greece. A 1982 amnesty law which stated "all Greek by descent who during the civil war of 1946–1949 and because of it have fled abroad as political refugees[64] had the right to return", thus excluding all those who did not identify as ethnic Greeks.[23]

This was brought to a forefront shortly after the independence of the Republic of Macedonia (now North Macedonia) in 1991. Many ethnic Macedonians have been refused entry to Greece because their documentation listed the Slavic names of the places of birth as opposed to the official Greek names, despite the child refugees, now elderly, only knowing their village by the local Macedonian name.[23] These measures were even extended to Australian and Canadian citizens. Despite this, there have been sporadic periods of free entry, most of which have only ever lasted a few days.

Despite the removal of official recognition to those identifying as ethnic Macedonians after the end of the Greek Civil War, a 1954 letter from the Prefect of Florina, K. Tousildis, reported that people were still affirming that the language they spoke was Macedonian in forms relating to personal documents, birth and marriage registries, etc.[65]

Recent history

Since the late 1980s there has been a Macedonian ethnic revival in much of Northern Greece,[66] especially where Macedonian speakers have not been minoritised.[67] In 1984 the "Movement for Human and National Rights for the Macedonians of Aegean Macedonia" was founded,[68] and was followed by the creation of the "Central Committee for Macedonian Human Rights" in Salonika in 1989.[69] In 1990 a manifesto by this group was presented to the Conference for Security and Co-operation in Europe on behalf of the ethnic Macedonians.[68] Following this the "Macedonian Movement for Balkan Prosperity" (MAKIVE) was formed, and in 1993 this group held the first "All Macedonian Congress" in Greece.[70] The bilingual Macedonian and Greek-language "Ta Moglena" newspaper was first put into print in 1989, and although restricted to the Moglena region had a readership of 3,000.[71] In 1989 the first attempts at establishing a "House of Macedonian Culture" in Florina began.[72] MAKIVE participated in the 1993 local elections and received 14 percent of the vote in the Florina Prefecture.[73]

According to a study by anthropologist Ricki van Boeschoten, 64% of the inhabitants of 43 villages in the Florina area were Macedonian-language speakers.[74] According to a 1993 study, of the 90 villages in Florina Prefecture, 50% were populated only by Slavic speakers, while another 23% with mixed population of Slavic speakers and other groups.[75] One study of the archives in Langadas and the Lake Koroneia basin in Thessaloniki Prefecture found that most of the 22 villages in the area contained a population primarily made up of former Slavic speakers.[76]

In January 1994, Rainbow (Macedonian: Виножито, romanized: Vinožito, Greek: Ουράνιο Τόξο, romanized: Ouránio Tóxo) was founded as the political party to represent the ethnic Macedonian minority. At the 1994 European Parliament election the party received 7,263 votes and polled 5.7% in the Florina district. The party opened its offices in Florina on September 6, 1995. The opening of the office faced strong hostility and that night the offices were ransacked.[77] In 1997 the "Zora" (Macedonian: Зора, lit. Dawn) newspaper first began to published and the following year,[78] the Second All-Macedonian congress was held in Florina. Soon after the "Makedoniko" magazine also began to be published.

In 2001 the first Macedonian Orthodox church in Greece was founded in the Aridaia region, which was followed in 2002 by the election of a Rainbow Candidate, Petros Dimtsis, to office in the Florina Prefecture. The year also saw the "Loza" (Macedonian: Лоза, lit. Vine) magazine go into print. In the following years several Macedonian-language radio stations were established, however many including "Makedonski Glas" (Macedonian: Македонски Глас, lit. Macedonian Voice), were shut down by Greek authorities.[79] During this period ethnic Macedonians such as Kostas Novakis began to record and distribute music in the native Macedonian dialects.[80] Ethnic Macedonian activists reprinted the language primer Abecedar (Macedonian: Абецедар), in attempt to encourage further use of the Macedonian language.[81] However, the lack of Macedonian-language literature has left many young ethnic Macedonian students dependent on textbooks from the Republic of Macedonia.[82] In 2008 thirty ethnic Macedonians from the villages of Lofoi, Meliti, Kella and Vevi protested against the presence of the Greek military in the Florina region.[83][84]

Another ethnic Macedonian organisation, the Educational and Cultural Movement of Edessa (Macedonian: Образовното и културно движење на Воден, romanized: Obrazovnoto i kulturnoto dviženje na Voden), was formed in 2009. Based in Edessa, the group focuses on promoting ethnic Macedonian culture, through the publication of books and CD's, whilst also running Macedonian-language courses and teaching the Macedonian Cyrillic alphabet.[85] Since then Macedonian-language courses have been extended to include Florina and Salonika.[86] Later that year Rainbow officially opened its second office in the town of Edessa.[87]

In early 2010 several Macedonian-language newspapers were put into print for the first time. In early 2010 the Zadruga (Macedonian: Задруга, Greek: Koinotita) newspaper was first published,[88] This was shortly followed by the publication of the "Nova Zora" newspaper in May 2010. The estimated readership of Nova Zora is 20,000, whilst that of Zadrgua is considerably smaller.[88] The "Krste Petkov Misirkov Foundation" was established in 2009, which aims to establish a museum dedicated to ethnic Macedonians of Greece, whilst also cooperating with other Macedonian minorities in neighbouring countries. The foundations aims at cataloguing ethnic Macedonian culture in Greece along with promoting the Macedonian language.[89][90]

In 2010 another group of ethnic Macedonians were elected to office, including the outspoken local chairman of Meliti, Pando Ašlakov.[91] According to reports from North Macedonia, ethnic Macedonians have also been elected as chairmen in the villages of Vevi, Pappagiannis, Neochoraki and Achlada.[91] Later that year the first Macedonian-Greek dictionary was launched by ethnic Macedonian activists in both Brussels and Athens.[92]

The Church of Saint Zlata of Meglen in Aridaia is the only Macedonian Orthodox Church in Greek Macedonia, operating under archimandrite Nikodim Tsarknias.[93]

Ethnic and linguistic affiliations

| Part of a series on |

| Greeks |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

History of Greece (Ancient · Byzantine · Ottoman) |

Members of this group have had a number of conflicting ethnic identifications. Predominantly identified as Macedonian Bulgarians until the early 1940s,[95][96] since the formation of a Macedonian nation state, many of the migrant population in the diaspora (Australia, United States and Canada) now feel a strong Macedonian identity and have followed the consolidation of the Macedonian ethnicity.[97] However, those who remain in Greece now mainly identify themselves as ethnic Greeks.[98][99] The Macedonian region of Greece has a Greek majority which includes descendants of the Pontic Greeks, but it is ethnically diverse (including Arvanites, Aromanians, Megleno-Romanians and Slavs).

The second group in today's Greece is made up of those who seem to reject any national identity, but have distinct regional ethnic identity, which they may call "indigenous" (Greek: ντόπια, dopia), which might be understood as Slavomacedonian, or Macedonian,[100] and the smallest group is made up of those who have a so-called ethnic Macedonian national identity.[101] They speak East South Slavic dialects that are usually linguistically classified as Macedonian,[102] but which are locally often referred to simply as "Slavic" or "the local language".

A crucial element of that controversy is the very name Macedonian, as it is also used by a much more numerous group of people with a Greek national identity to indicate their regional identity. The term "Aegean Macedonians" (Macedonian: Егејски Македонци, Egejski Makedonci), mainly used in North Macedonia and in the irredentist context of a United Macedonia, is associated with those parts of the population that have a so-called ethnic Macedonian identity.[103] Speakers who identify as Greeks or have distinct regional ethnic identity, often speak of themselves simply as "locals" (Greek: ντόπιοι, dopii), to distinguish themselves from native Greek speakers from the rest of Greece and/or Greek refugees from Asia Minor who entered the area in the 1920s and after.

Some Slavic speakers in Greek Macedonia will also use the term "Macedonians" or "Slavomacedonians", though in a regional rather than an ethnic sense. People of Greek persuasion are sometimes called by the pejorative term "Grecomans" by the other side. Greek sources, which usually avoid the identification of the group with the nation of North Macedonia, and also reject the use of the name "Macedonian" for the latter, will most often refer only to so-called "Slavophones" or "Slavophone Greeks".

"Slavic speakers" or "Slavophones" is also used as a cover term for people across the different ethnic orientations. The exact number of this minority remaining in Greece today, together with its members' choice of ethnic identification, is difficult to ascertain; most maximum estimates range around 180,000–200,000 with those of an ethnic Macedonian national consciousness numbering possibly 10,000 to 30,000.[104] However, as per leading experts on this issue, the number of this people has decreased in the last decades, because of intermarriage and urbanization; they now number between 50,000 and 70,000 people with around 10,000 of them identifying as ethnic Macedonians.[105][106][107][108][109]

Past discrimination

After the conclusion of the First World War a widespread policy of Hellenisation was implemented in the Greek region of Macedonia[23][110][111] with personal and topographic names forcibly changed to Greek versions[112] and Cyrillic inscriptions across Northern Greece being removed from gravestones and churches.[112][113]

Under the regime of Ioannis Metaxas the situation for Slavic speakers became intolerable, causing many to emigrate. A law was passed banning the Bulgarian language (local Macedonian dialects).[114][115] Many people who broke the rule were deported to the islands of Thasos and Cephalonia.[116] Others were arrested, fined, beaten and forced to drink castor oil,[110] or even deported to the border regions in Yugoslavia[58] following a staunch government policy of chastising minorities.[117]

During the Greek Civil War, areas under Communist control freely taught the newly codified Macedonian language. Throughout this period it is claimed that the ethnic Macedonian culture and language flourished.[118] Over 10,000 children went to 87 schools, Macedonian-language newspapers were printed and theatres opened. As the National forces approached, these facilities were either shut down or destroyed. People feared oppression and the loss of their rights under the rule of the National government, which in turn caused many people to flee from Greece.[16][119] However, the Greek Communists were defeated in the civil war, their Provisional Government was exiled, and tens of thousands of Slavic speakers were expelled from Greece.[120][121] Many fled in order to avoid persecution from the ensuing National army.[122][123] Those who fled during the Greek Civil War were stripped of their Greek Citizenship and property.[124] Although these refugees have been classed as political refugees, there have been claims that they were also targeted due to their ethnic and cultural identities.

During the Cold War cases of discrimination against people who identified themselves as ethnic Macedonians, and against the Macedonian language, had been reported by Human Rights Watch/Helsinki.[23] In 1959 it was reported that the inhabitants of three villages adopted a 'language oath', renouncing their Slavic dialect.[23] According to Riki Van Boeschoten, this "peculiar ritual" took place "probably on the initiative of local government officials."[125]

According to a 1994 report by the Human Rights Watch, based on a fact-finding mission in 1993 in the Florina Prefecture and Bitola, Greece oppressed the ethnic Macedonians and implemented a program to forcefully Hellenize them.[23] According to its findings, the ethnic Macedonian minority was denied acknowledgment of its existence by the Greek government, which refused the teaching of their language and other expressions of ethnic Macedonian culture; members of the minority "were discriminated against in employment in the public sector in the past, and may suffer from such discrimination at present"; minority activists "have been prosecuted and convicted for the peaceful expression of their views" and were generally "harassed by the government, followed and threatened by security forces, and subjected to economic and social pressures resulting from government harassment", leading to a climate of fear.[23] The Greek government further discriminated against ethnic Macedonian refugees who fled into Yugoslavia during the Greek Civil War; while Greek political refugees were allowed to reclaim their citizenship, they were not.[23]

The Greek state requires radio stations to broadcast in Greek, therefore excluding the Slavic speakers of Greek Macedonia (who are considered ethnic Macedonians by the Rainbow political party) from operating radio stations in Slavic.[126]

Culture

Regardless of political orientation, Macedonian speakers in Greece share a common culture with ethnic Macedonians.[127][128][129] The commonalities include religious festivals, dances, music, language, folklore and national dress. Despite these commonalities however, there are regional folk dances which are specific to persons living in Greece. However, waves of refugees and emigration have had the effect of spreading this culture far beyond the borders of Greece.[130]

Greece has blocked attempts by ethnic Macedonians to establish a Home of Macedonian Culture despite being convicted for a violation of freedom of association by the European Court of Human Rights.[131]

Traditions

Koleda, an ancient Slavic winter ritual, is widely celebrated across northern Greece by Slavic speakers, in areas from Florina to Thessaloniki, where it is called Koleda (Κόλεντε, Κόλιαντα) or Koleda Babo (Κόλιντα Μπάμπω) which means "Koleda Grandmother" in Slavic. It is celebrated around Christmas by gathering in the village square and lighting a bonfire, followed by local Macedonian music and dancing.

Winter traditions that are characteristic to Slavic speakers in Greece, Bulgaria and North Macedonia include Babaria (Greek: Μπαμπάρια; Macedonian: Бабари; Bulgarian: Бабугери) in the Florina area, Ezarki (Greek: Εζζκάρι; Macedonian: Ежкари; Bulgarian: Ешкари) in the Ptolemaida area, Rogochari (Greek: Ρογκοτσσάρι; Macedonian: Рогочари; Bulgarian: Рогочари) in the Kastoria area, and Dzamalari (Greek: Τζζαμαλάρι; Macedonian: Џамалари; Bulgarian: Джамалари/Джамали) in the Edessa area.[132][133]

Music

Many regional folk songs are performed in both the local Macedonian dialects and Standard Macedonian language, depending on the origin of the song. However, this was not always the case, and in 1993 the Greek Helsinki Monitor found that the Greek government refused in "the recent past to permit the performance of [ethnic] Macedonian songs and dances".[134] In recent years however these restrictions have been lifted and once again Macedonian songs are performed freely at festivals and gatherings across Greece.[23][135]

Many songs originating Greek Macedonia such as "Filka Moma" (Macedonian: Филка Мома, lit. Filka Girl) have become popular in North Macedonia. Whilst likewise many songs composed by artists from North Macedonia such as "Egejska Maka" by Suzana Spasovska, "Makedonsko devojče" by Jonče Hristovski,[136] and "Kade ste Makedončinja?" are also widely sung in Greece.[137] In recent years many ethnic Macedonian performers including Elena Velevska, Suzana Spasovska, Ferus Mustafov, Group Synthesis and Vaska Ilieva, have all been invited to perform in amongst ethnic Macedonians in Greece.[138][139] Likewise ethnic Macedonian performers from Greece such as Kostas Novakis also perform in North Macedonia.[140] Many performers who live in the diaspora often return to Greece to perform Macedonian songs, including Marija Dimkova.[141]

Dances

The Lerinsko oro/lerin dance, with origins in the region of Florina, is also popular amongst Slavic speakers. Other dances popularized by the Boys from Buf include the Bufsko Pušteno and Armensko Oro.

Media

The first Macedonian-language media in Greece emerged in the 1940s. The "Crvena Zvezda" newspaper, first published in 1942 in the local Solun-Voden dialect, is often credited with being the first Macedonian-language newspaper to be published in Greece.[142] This was soon followed by the publication of many others including, "Edinstvo" (Unity), "Sloveno-Makedonski Glas", "Nova Makedonka", "Freedom", "Pobeda" (Victory), "Prespanski Glas" (Voice of Prespa), "Iskra" (Spark), "Stražar" (Guard) and others.[142] Most of these newspapers were written in the codified Macedonian language or the local Macedonian dialects. The Nepokoren (Macedonian: Непокорен) newspaper was issued from May 1, 1947, until August 1949, and served as a later example of Macedonian-language media in Greece. It was affiliated with the National Liberation Front, which was the military organisation of the Ethnic Macedonian minority in Greece. The Bilten magazine (Macedonian: Билтен), is another example of Greek Civil War era Macedonian media.[143]

After the Greek Civil War a ban was placed on public use of Macedonian, and this was reflect in the decline of all Macedonian-language media. The 1990s saw a resurgence of Macedonian-language print including the publication of the "Ta Moglena", Loza, Zora (Macedonian: Зора) and Makedoniko newspapers. This was followed with the publication of the Zadruga magazine (Macedonian: Задруга) in early 2010.[144] Soon afterwards in May 2010 the monthly newspaper Nova Zora (Macedonian: Нова Зора)[145] went to print. Both Zadruga and Nova Zora are published in both Macedonian and Greek.

Several Macedonian-language radio stations have recently been set up in Greek Macedonia to cater for the Macedonian speaking population.[146] These stations however, like other Macedonian-language institutions in Greece have faced fierce opposition from the authorities, with one of these radio stations, "Macedonian Voice" (Macedonian: Македонски Глас), being shut down by authorities.[79]

Education and language

The Slavic dialects spoken across Northern Greece belong to the eastern group of South Slavic, comprising Bulgarian and Macedonian, and share all the characteristics that set this group apart from other Slavic languages: existence of a definite article, lack of cases, lack of a verb infinitive, comparative forms of adjectives formed with the prefix по-, future tense formed by the present form of the verb preceded by ще/ќе, and existence of a renarrative mood.[147] These dialects include the Upper and Lower Prespa dialects, the Kostur, Nestram-Kostenar, Ser-Drama-Lagadin-Nevrokop dialect, and Solun-Voden dialects. The Prilep-Bitola dialect is widely spoken in the Florina region, and forms the basis of the Standard Macedonian language. The majority of the speakers also speak Greek, this trend is more pronounced amongst younger persons.

Speakers employ various terms to refer to the language which they speak. These terms include Makedonski (Macedonian: Македонски), Slavomakedonika (Greek: Σλαβομακεδονικά, "Slavomacedonian"), Entopia (Greek: Εντόπια, "local" language), Naše (Macedonian: Наше, "our own" language), Starski (Macedonian: Старски, "the old" language) or Slavika (Greek: Σλαβικά, "Slavic"). Historically, the terms Balgàrtzki, Bolgàrtski or Bulgàrtski had been used in the region of Kostur (Kastoria), and Bògartski ("Bulgarian") in the region of Lower Prespa (Prespes).[148]

According to Peter Trudgill,

There is, of course, the very interesting Ausbau sociolinguistic question as to whether the language they speak is Bulgarian or Macedonian, given that both these languages have developed out of the South Slavonic dialect continuum...In former Yugoslav Macedonia and Bulgaria there is no problem, of course. Bulgarians are considered to speak Bulgarian and Macedonians Macedonian. The Slavonic dialects of Greece, however, are "roofless" dialects whose speakers have no access to education in the standard languages. Greek non-linguists, when they acknowledge the existence of these dialects at all, frequently refer to them by the label Slavika, which has the implication of denying that they have any connection with the languages of the neighboring countries. It seems most sensible, in fact, to refer to the language of the Pomaks as Bulgarian and to that of the Christian Slavonic-speakers in Greek Macedonia as Macedonian.[149]

Until the middle of the nineteenth century the language of instruction in virtually all schools in the region was Greek. One of the first Bulgarian schools began operation in 1857 in Kukush.[150] The number of Bulgarian schools increased as the Bulgarian struggle for ecclesiastical independence intensified and after the establishment of the Bulgarian Exarchate in 1870. According to the statistics of the Bulgarian Exarchate, by 1912, when the First Balkan War broke out, there were 296 Bulgarian schools with 589 teachers and approximately 19 000 pupils in Greek Macedonia.[151] For comparison, the total number of Bulgarian-exarchist schools in all of Macedonia in 1912 was 1196 with 2096 teachers and 70 000 pupils.[152] All Bulgarian schools in Greek and Serbian Macedonia were closed after the Second Balkan War. The Abecedar language primer, originally printed in 1925, was designed for speakers in using the Prilep-Bitola dialect in the Florina area. Although the book used a Latin script, it was printed in the locally Prilep-Bitola dialect. In the 1930s the Metaxas regime banned the use of the Slavomacedonian language in public and private use. Laws were enacted banning the language,[114][115] and speakers faced harsh penalties including being arrested, fined, beaten and forced to drink castor oil.[110]

During the Axis occupation of Greece during World War II however these penalties were lifted. Macedonian was employed in widespread use, with Macedonian-language newspapers appearing from 1942.[153] During the period 1941–1944 within The Bulgarian occupation zone Bulgarian was taught.

During the Greek Civil War, the codified Macedonian language was taught in 87 schools with 10,000 students in areas of northern Greece under the control of Communist-led forces, until their defeat by the National Army in 1949.[154] After the war, all of these Macedonian-language schools were closed down.[155]

More recently there have been attempts to once again begin education in Macedonian. In 2009 the Educational and Cultural Movement of Edessa began to run Macedonian-language courses, teaching the Macedonian Cyrillic alphabet.[85] Macedonian-language courses have also begun in Salonika, as a way of further encouraging use of Macedonian.[156] These courses have since been extended to include Macedonian speakers in Florina and Edessa.[157]

In 2006 the Macedonian-language primer Abecedar was reprinted in an informal attempt to reintroduce Macedonian-language education[81] The Abecedar primer was reprinted in 2006 by the Rainbow Political Party, it was printed in Macedonian, Greek and English. In the absence of more Macedonian-language books printed in Greece, young ethnic Macedonians living in Greece use books originating from North Macedonia.[82]

Today Macedonian dialects are freely spoken in Greece however there are serious fears for the loss the language among the younger generations due to the lack of exposure to their native language. It appears however that reports of the demise of the use of Macedonian in Greece have been premature, with linguists such as Christian Voss asserting that the language has a "stable future" in Greece, and that the language is undergoing a "revival" amongst younger speakers.[158] The Rainbow Party has called for the introduction of the language in schools and for official purposes. They have been joined by others such as Pande Ašlakov, mayor of Meliti, in calling for the language to be officially introduced into the education system.[159]

Certain characteristics of these dialects, along with most varieties of Spoken Macedonian, include the changing of the suffix ovi to oj creating the words lebovi → leboj (лебови → лебој, "bread").[160] Often the intervocalic consonants of /v/, /ɡ/ and /d/ are lost, changing words from polovina → polojna ("a half") and sega → sea ("now"), which also features strongly in dialects spoken in North Macedonia.[161] In other phonological and morphological characteristics, they remain similar to the other South-Eastern dialects spoken in North Macedonia and Albania.[162]

On 27 July 2022,[163] in a landmark ruling, the Centre for the Macedonian Language in Greece was officially registered as a non-governmental organization. This is the first time that a cultural organization promoting the Macedonian language has been legally approved in Greece and the first legal recognition of the Macedonian language in Greece since at least 1928.[164][165][166][29]

Diaspora

Outside of Greece there is a large diaspora to be found in the North Macedonia, former Eastern Bloc countries such as Bulgaria, as well as in other European and overseas countries.

Bulgaria

The most numerous Slavic diaspora from Greece lives in Bulgaria. There were a number of refugee waves, most notably after the Treaty of Berlin and the Kresna-Razlog Uprising (1878), the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising (1903), during the Balkan Wars (1912–1913), and after World War I (1918).[167] According to some estimates, by the beginning of the Balkan Wars, the total number of refugees from Macedonia and Thrace was about 120,000.[167] Others estimate that by the middle of the 1890s between 100,000 and 200,000 Slavs from Macedonia had already immigrated to Bulgaria.[168] Around 100 000 Bulgarians fled to Bulgaria from the districts around Koukush before the advancing Greek army during the Second Balkan War.[169] 66 000 more left Greece for Bulgaria after the end of World War I, following a population exchange agreement between Bulgaria and Greece.[170]

The refugees and their various organizations played an active role in Bulgarian public and political life: at the end of the 19th century they comprised about a third of the officers in the army (430 out of 1289), 43% of government officials (15 000 out of 38 000), 37% of the priests of the Bulgarian Exarchate (1,262 out of 3,412), and a third of the capital's population.[168] The Supreme Macedonian-Adrianople Committee and the Macedonian Scientific Institute are among the most notable organizations founded by Macedonian Bulgarian immigrants to Bulgaria.

North Macedonia

The state of North Macedonia is home to thousands of people who self-identify as "Aegean Macedonians". Sources put the number of Aegean Macedonians living in North Macedonia at somewhere between 50,000 and 70,000.[15] The majority of these people are descended from World War II and Greek Civil War refugees who fled to the then Bulgarian-occupied Yugoslav Macedonia and People's Republic of Macedonia. The years following the conflict saw the repatriation of many refugees mainly from Eastern Bloc countries. The refugees were primarily settled in deserted villages and areas across Yugoslav Macedonia. A large proportion went to the Tetovo and Gostivar areas. Another large group was to settle in Bitola and the surrounding areas, while refugee camps were established in Kumanovo and Strumica. Large enclaves of Greek refugees and their descendants can be found in the suburbs of Topansko Pole and Avtokamanda in Skopje. Many Aegean Macedonians have held prominent positions in North Macedonia, including former prime minister Nikola Gruevski and Dimitar Dimitrov, the former Minister of Education.

Australia

A large self-identifying Aegean Macedonian population also lives in Australia, many of which arrived during the early 1900s. Charles Price estimates that by 1940 there were 670 Ethnic Macedonians from Florina and 370 from Kastoria resident in Australia. The group was a key supporter of the Macedonian-Australian People's League, and since then has formed numerous emigrant organisations.[171] There are Aegean Macedonian communities in Richmond, Melbourne, Manjimup,[172] Shepparton, Wanneroo and Queanbeyan.[173] These immigrants have established numerous cultural and social groups including The Church of St George and the Lerin Community Centre in Shepparton and the Aegean Macedonian hall – Kotori built in Richmond along with other churches and halls being built in Queanbeyan in Manjimup.[16] The "Macedonian Aegean Association of Australia" is the uniting body for this community in Australia.[16] It has been estimated by scholar Peter Hill that over 50,000 Aegean Macedonians and their descendants can be found in Australia.[174]

Canada

Large populations of Macedonians emigrated to Canada in the wake of the failed Ilinden Uprising and as Pečalbari (lit. Seasonal Workers) in the early 1900s. An internal census revealed that by 1910 the majority of these people were from the Florina (Lerin) and Kastoria (Kostur) regions.[175] By 1940 this number had grown to over 1,200 families, primarily concentrated in the Toronto region.[175] A further 6,000 ethnic Macedonians are estimated to have arrived as refugees, following the aftermath of the Greek Civil War.[176] One of the many cultural and benevolent societies established included "The Association of Refugee Children from Aegean Macedonia" (ARCAM) founded in 1979. The association aimed to unite former child refugees from all over the world, with branches soon established in Toronto, Melbourne, Perth, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Poland and Macedonia.[177]

Romania

In the aftermath of the Greek Civil War thousands of ethnic Bulgarian and ethnic Macedonian refugees were displaced to Romania. Between 1948 and 1949 an estimated 5,200 child refugees, all ethnic Bulgarian, Macedonian and Greek were sent to Romania. The largest of the evacuation camps was set up in the town of Tulgheş, and here all the refugees were schooled in Greek and the ethnic Macedonian also in Macedonian; other languages were Romanian and Russian.[3]

United States

Most of the Slavic-speaking immigrants from Macedonia arrived in the United States during the first decade of the twentieth century. Between 1903 and 1906 an estimated 50,000 Slavic-speaking migrants from Macedonia came to the United States. These identified themselves as either Bulgarians or Macedonian Bulgarians. Their most prominent organisation, the Macedonian Political Organisation was established in Fort Wayne, Indiana, in 1922 (it was renamed to Macedonian Patriotic Organisation in 1952).[178]

Notable persons

- Dimitar Blagoev, politician and philsopher

- Vasil Chekalarov, revolutionary, IMRO leader

- Atanas Dalchev, poet, critic, and translator

- Gotse Delchev, revolutionary, IMRO leader

- Dimitar Dimitrov, politician

- Kostadin Hristov

- Angelis Gatsos, Greek revolutionary

- Andon Kalchev, officer in the Bulgarian Army, Ohrana member

- Risto Kirjazovski

- Stojan Kočov

- Jagnula Kunovska

- Krste Misirkov, Philologist, journalist, historian and ethnographer

- Paskal Mitrevski

- Kroum Pindoff

- Lazar Poptraykov, revolutionary, IMRO leader

- Lyubka Rondova, Bulgarian[179][180][181] folk singer

- Andrew Rossos

- Blagoy Shklifov, dialectologist[182][183]

- Steve Stavro

- Georgi Traykov, politician, Head of State of Bulgaria (1964–1971)

- Nikodim Tsarknias, monk

- Andreas Tsipas

- Dimitar Vlahov, politician and revolutionary

- Pavlos Voskopoulos

- Anton Yugov, member of the Bulgarian Communist Party, Prime Minister of Bulgaria (1956–1962)

- Hristo Smirnenski, writer and poet[184]

See also

References

- ↑ "Macedonian". Ethnologue. 1999-02-19. Retrieved 2015-08-31.

- ↑ Jacques Bacid (1983). Macedonia Through the Ages. Columbia University.

- 1 2 Danforth, Loring M. The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World 1995. Princeton University Press.

- ↑ "UCLA Language Materials Project: Language Profile". Lmp.ucla.edu. Archived from the original on 2011-02-09. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ "UCLA Language Materials Project: Language Profile". Lmp.ucla.edu. Archived from the original on 2011-06-05. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ "National Conflict in a Transnational World: Greeks and Macedonians at the CSCE". Gate.net. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ Poulton, Hugh (1995). Who are the Macedonians?. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 167. ISBN 1-85065-238-4.

- ↑ Shea, John (1994-11-15). Macedonia and Greece: The Struggle to Define a New Balkan Nation – John Shea – Google Books. McFarland. ISBN 9780786402281. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ "Greece". State.gov. 2002-03-04. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ Loring M. Danforth (1997). The Macedonian Conflict. Princeton University Press. p. 69. ISBN 9780691043562.

- ↑ Howard Jones (1997). A new kind of war. Oxford University Press US. p. 69. ISBN 9780195113853.

- ↑ John S. Koliopoulos (1999). Plundered loyalties: Axis occupation and civil strife in Greek West Macedonia, 1941–1949. C. Hurst & Co. p. 35. ISBN 1-85065-381-X.

- ↑ "20680-Ancestry by Country of Birth of Parents – Time Series Statistics (2001, 2006 Census Years) – Australia". 1 October 2007. Archived from the original on 1 October 2007. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ↑ The Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation, 1988, James Jupp (Editor), Angus & Robertson, Sydney.

- 1 2 Simpson, Neil (1994). Macedonia Its Disputed History. Victoria: Aristoc Press. pp. 92. ISBN 0-646-20462-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Peter, Hill. (1989) The Macedonians in Australia, Hesperian Press, Carlisle

- ↑ Stephan Thernstrom; Ann Orlov; Oscar Handlin (1980). Harvard encyclopedia of American ethnic groups. Harvard University Press. p. 691. ISBN 9780674375123.

- ↑ A charter of Romanus II, 960 Pulcherius (Slav-Bulgarian population in Chalcidice Peninsula is mentioned), Recueil des historiens des Croisades. Historiens orientaux. III, p. 331 – a passage in English Georgii Cedreni compendium, op. cit, pp. 449–456 – a passage in English (Bulgarian population in Servia is mentioned) In the so-called Legend of Thessaloniki (12th c.) it is said that the Bulgarian language was also spoken hi the market place of Thessaloniki, Documents of the notary Manoli Braschiano concerning the sale and liberation of slaves of Bulgarian nationality from Macedonia (Kastoria, Seres, region of Thessaloniki etc.), From the Third Zograf Beadroll, containing the names of donors to the Zograf Monastery at Mt. Athos from settlements and regions indicated as Bulgarian lands, Evidence from the Venetian Ambassador Lorenzo Bernardo on the Bulgarian character of the settlements in Macedonia

- ↑ Венециански документи за историята на България и българите от ХІІ-XV век, София 2001, с. 150, 188/Documenta Veneta historiam Bulgariae et Bulgarorum illustrantia saeculis XII-XV, p. 150, 188, edidit Vassil Gjuzelev (Venetian documents for the history of Bulgaria and Bulgarians, p. 150, 188 – Venetian documents from 14–15th century about slaves from South Macedonia with Bulgarian belonging/origin)

- ↑ Journal of Modern Greek Studies 14.2 (1996) 253–301 Nationalism and Identity Politics in the Balkans: Greece and the Macedonian Question by Victor Roudometof.

- ↑ Vakalopoulos, A. Konstantinos (1983). The northern Hellenism during the early phase of the Greek struggle for Macedonia (1878–1894). Institute for Balkan Studies. p. 190.

- ↑ The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. Dennis Hupchik

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 HRW 1994, p. ?.

- ↑ Ivo Banac, "The Macedoine" in "The National Question in Yugoslavia. Origins, History, Politics", pp. 307–328, Cornell University Press, 1984, retrieved on September 8, 2007.

- ↑ Nationality on the Balkans. The case of the Macedonians, by F. A. K. Yasamee. (Balkans: A Mirror of the New World Order, Istanbul: EREN, 1995; pp. 121–132.

- ↑ Даскалов, Георги. Българите в Егейска Македония. Rсторико-демографско изследване /1900–1990/, София, Македонски научен институт, 1996, с. 165 (Daskalov, Georgi. The Bulgarians in Aegean Macedonia. Historical-Demographic research /1900–1990/, Sofia, published by Macedonian Scientific Institute, 1996, p. 165.)

- ↑ Theodor Capidan, Meglenoromânii, istoria şi graiul lor Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, vol. I, București, 1925, p.5, 19, 21–22.

- ↑ "Резолюция о македонской нации (принятой Балканском секретариате Коминтерна" – Февраль 1934 г, Москва

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mavrogordatos, George. Stillborn Republic: Social Coalitions and Party Strategies in Greece, 1922–1936. University of California Press, 1983. ISBN 9780520043589, p. 227, 247

- 1 2 3 Miller, Marshall Lee (1975). Bulgaria During the Second World War. Stanford University Press. p. 129. ISBN 0-8047-0870-3.

In Greece the Bulgarians reacquired their former territory, extending along the Aegean coast from the Struma (Strymon) River east of Salonika to Dedeagach (Alexandroupolis) on the Turkish border. Bulgaria looked longingly toward Salonika and western Macedonia, which were under German and Italian control, and established propaganda centres to secure the allegiance of the approximately 80,000 Slavs in these regions. The Bulgarian plan was to organize these Slavs militarily in the hope that Bulgaria would eventually assume the administration there. The appearance of Greek partisans in western Macedonia persuaded the Italian and German authorities to allow the formation of Slav security battalions (Ohrana) led by Bulgarian officers.

- ↑ Danforth, Loring M. (1995). The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-691-04357-9.

- ↑ Woodhouse, Christopher Montague (2002). The struggle for Greece, 1941–1949. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 67. ISBN 1-85065-492-1.

- ↑ Max, Ben. "atrocities during the greek civil war".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Mazower (2000), p. 276

- ↑ Uranros, 103-4.

- ↑ Makedonia newspaper, 11 May 1948.

- ↑ Cowan, Jane K. (2000). Macedonia: the politics of identity and difference. Sydney: Pluto Press. p. 73. ISBN 0-7453-1589-5.

He also played a leading part in effecting a rapprochement between the GCP (Greek Communist Party) and Ohrana

- ↑ Fritz August Voigt (1949). Pax Britannica. Constable. p. 94.

Collaboration between the Ohrana, under Bulgarian control, and SNOF, under the control of EAM, and, therefore, of the Greek Communist Party

- ↑ "Collaboration between the Bulgarian-controlled Ohrana and the EAM -controlled SNOF followed upon an agreement that Macedonia should become autonomous". The Nineteenth Century and After. A. D. Caratzas: 12. 1946.

- ↑ Kophos, Euangelos; Kōphos, Euangelos (1993). Nationalism and communism in Macedonia: civil conflict, politics of mutation, national identity. New Rochelle, N.Y: A. D. Caratzas. p. 125. ISBN 0-89241-540-1.

By September, entire Ohrana units had joined the SNOF which, in turn, began to press the ELAS leadership to allow it to raise the SNOF battalion to division

- ↑ John S. Koliopoulos (1999). Plundered loyalties: Axis occupation and civil strife in Greek West Macedonia, 1941–1949. C. Hurst & Co. p. 53. ISBN 1-85065-381-X.

- ↑ F0371/58615, Thessaloniki consular report of 24 Sep. 1946

- ↑ Karloukovski, Vassil. "C. Jonchev – Bylgarija i Belomorieto – 3a". macedonia.kroraina.com. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ↑ Karloukovski, Vassil. "D. Jonchev – Bylgarija i Belomorieto – 3b". macedonia.kroraina.com. Retrieved 18 October 2017.

- ↑ Incompatible Allies: Greek Communism and Macedonian Nationalism in the Civil War in Greece, 1943–1949, Andrew Rossos – The Journal of Modern History 69 (March 1997): 42

- ↑ KKE, Πέντε Χρόνια Αγώνες 1931–1936, Athens, 2nd ed., 1946.

- ↑ "Славјано Македонски Глас", 15 Јануари 1944 с.1

- ↑ "АМ, Збирка: Егејска Македонија во НОБ 1941–1945 – (Повик на СНОФ до Македонците од Костурско 16 Мај 1944)"

- ↑ "Народно Ослободителниот Фронт и други организации на Македонците од Егејскиот дел на Македонија. (Ристо Кирјазовски)", Скопје, 1985.

- ↑ HRW 1994, p. 9.

- ↑ John S. Koliopoulos. Plundered Loyalties: World War II and Civil War in Greek West Macedonia. Foreword by C. M. Woodhouse. New York: New York University Press. 1999. p. 304.

- ↑ "H-Net Reviews". H-net.msu.edu. January 1996. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ Cook, Bernard A. (2001). Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780815340584. Retrieved 2015-09-05.

- ↑ Yugoslavia: A History of Its Demise, Viktor Meier, Routledge, 2013, ISBN 1134665113, p. 183.

- ↑ Hugh Poulton Who are the Macedonians?, C. Hurst & Co, 2000, ISBN 1-85065-534-0. pp. 107–108.

- ↑ "Les Archives de la Macedonine, Fond: Aegean Macedonia in NLW" – (Field report of Mihail Keramidzhiev to the Main Command of NOF), 8 July 1945

- ↑ "Η Τραγική αναμέτρηση, 1945–1949 – Ο μύθος και η αλήθεια. Ζαούσης Αλέξανδρος" (ISBN 9607213432).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Simpson, Neil (1994). Macedonia Its Disputed History. Victoria: Aristoc Press. pp. 101, 102 & 91. ISBN 0-646-20462-9.

- ↑ Ζαούσης Αλέξανδρος. Η Τραγική αναμέτρηση, 1945–1949 – Ο μύθος και η αλήθεια (ISBN 9607213432).

- ↑ Speech presented by Nikos Zachariadis at the Second Congress of the NOF (National Liberation Front of the ethnic Macedonians from Greek Macedonia), published in Σαράντα Χρόνια του ΚΚΕ 1918–1958, Athens, 1958, p. 575.

- ↑ "Macedonian Library – Македонска Библиотека". Macedonian.atspace.com. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ report of General consultant of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia addressed to foreign ministry of Greece Doc 47 15-7-1951 SMIR, ΡΑ, Grcka, 1951, f-30, d-21,410429, (έκθεση του γενικού προξενείου της Γιουγκοσλαβίας στη Θεσσαλονίκη SMIR, ΡΑ, Grcka, 1951, f-30, d-21,410429, Γενικό Προξενείο της Ομόσπονδης Λαϊκής Δημοκρατίας της Γιουγκοσλαβίας προς Υπουργείο Εξωτερικών, Αρ. Εγγρ. 47, Θεσσαλονίκη 15.7.1951. (translated and published by Spiros Sfetas . ΛΓ΄, Θεσσαλονίκη 2001–2002 by the Macedonian Studies )

- ↑ 3rd KKE congress 10–14 October 1950: Situation and problems of the political refugees in People's Republics pages 263–311 (3η Συνδιάσκεψη του Κόμματος (10–14 October 1950. Βλέπε: "III Συνδιάσκεψη του ΚΚΕ, εισηγήσεις, λόγοι, αποφάσεις – Μόνο για εσωκομματική χρήση – Εισήγηση Β. Μπαρτζιώτα: Η κατάσταση και τα προβλήματα των πολιτικών προσφύγων στις Λαϊκές Δημοκρατίες", σελ. 263 – 311") Quote: "Total number of political refugees : 55,881 (23,028 men, 14,956 women and 17,596 children, 368 unknown or not accounted)"

- ↑ Jane K. Cowan (20 December 2000). Macedonia: The Politics of Identity and Difference. Pluto Press. pp. 38–. ISBN 978-0-7453-1589-8.

- ↑ "Μητρικη Γλωσσα Η Μακεδονικη | Нова Зора –". Novazora.gr. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ Voss, Christian (2007). "Language ideology between self-identification and ascription among the Slavic speakers in Greek Macedonia and Thrace". In Steinke, K; Voß, Ch (eds.). The Pomaks in Greece and Bulgaria – a model case for borderland minorities in the Balkans. Munich. pp. 177–192.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Detrez, Raymond; Plas, Pieter (2005). Developing cultural identity in the Balkans: convergence vs divergence. Peter Lang. p. 50. ISBN 90-5201-297-0.

- 1 2 Shea, John (1997). Macedonia and Greece: The Struggle to Define a New Balkan Nation. McFarland. p. 147. ISBN 0-7864-3767-7.

- ↑ Bugajski, Janusz (1995). Ethnic politics in Eastern Europe: a guide to nationality policies, organizations, and parties. M.E. Sharpe. p. 177. ISBN 1-56324-283-4.

- ↑ Bugajski, Janusz (2002). Political parties of Eastern Europe: a guide to politics in the post-Communist era. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 769.

- ↑ HRW 1994, p. 39.

- ↑ Forward, Jean S. (2001). Endangered peoples of Europe: struggles to survive and thrive. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 95.

- ↑ Poulton, Hugh (2000). Who are the Macedonians?. C. Hurst & Co. p. 166. ISBN 1-85065-534-0.

- ↑ Riki Van Boeschoten (2001). Usage des langues minoritaires dans les départements de Florina et d'Aridea (Macédoine) (Use of minority languages in the districts of Florina and Aridea (Macedonia). Strates [online], Number 10. Villageois et citadins de Grèce (Villagers and Citizens of Greece), 11 January 2005

- ↑ Clogg, Richard (2002). Minorities in Greece: Aspects of a Plural Society. Hurst. ISBN 9781850657057.

- ↑ Fields of Wheat, Hills of Blood. University of Chicago Press. p. 250.

- ↑ "Greek Helsinki Monitor & Minority Rights Group – Greece; Greece against its Macedonian minority" (PDF). Greekhelsinki.gr. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-12-09. Retrieved 2015-09-05.

- ↑ Liotta, P. H. (2001). Dismembering the state: the death of Yugoslavia and why it matters. Lexington Books. p. 293. ISBN 0-7391-0212-5.

- 1 2 "Page Redirection". A1.com.mk. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ "Ελευθεροτυπία | Απογευματινή Αδέσμευτη Εφημερίδα". Archive.enet.gr. 2014-11-14. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- 1 2 TJ-Hosting. "EFA-Rainbow :: Abecedar". Florina.org. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- 1 2 "Македонскиот јазик во Грција има стабилна иднина". Mn.mk. 2015-02-09. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ "ДНЕВНИК: Грција експроприра во Леринско – Net Press". 2012-03-23. Archived from the original on 2012-03-23. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ "Македонците од Овчарани со камбани против грчки тенкови". 2012-03-23. Archived from the original on 2012-03-23. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- 1 2 "ΜΟΡΦΩΤΙΚΗ και ΠΟΛΙΤΙΣΤΙΚΗ ΚΙΝΗΣΗ ΕΔΕΣΣΑΣ". Edessavoden.gr. Archived from the original on 2015-08-01. Retrieved 2015-08-31.

- ↑ "Во Грција ќе никне училиште на македонски јазик?". Radiolav.com.mk. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ "EFA-Rainbow :: Macedonian Political Party in Greece". Florina.org. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- 1 2 "Втор весник на Македонците во Грција – Нова Македонија". Novamakedonija.com.mk. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ "Page Redirection". A1.com.mk. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- ↑ "EFA-Rainbow :: Macedonian Political Party in Greece". Florina.org. Retrieved 2015-09-04.

- 1 2 "TIME.mk - страница за вести". Archived from the original on 2012-09-12. Retrieved 2011-07-21.

- ↑ "Грција индиректно финансира македонско-грчки речник | Балкан | DW.DE | 22.06.2011". Archived from the original on 2013-02-19. Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- ↑ "Покана од архимандритот Царкњас на литургија во чест на Света Злата Мегленска во С'ботско, Грција". MKD.mk. 26 October 2022.

- ↑ See Ethnologue (); Euromosaic, Le (slavo)macédonien / bulgare en Grèce, L'arvanite / albanais en Grèce, Le valaque/aromoune-aroumane en Grèce, and Mercator-Education: European Network for Regional or Minority Languages and Education, The Turkish language in education in Greece. cf. also P. Trudgill, "Greece and European Turkey: From Religious to Linguistic Identity", in S. Barbour, C. Carmichael (eds.), Language and Nationalism in Europe, Oxford University Press 2000.

- ↑ Poulton, Hugh (1995). Who are the Macedonians?. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 109. ISBN 1-85065-238-4.

- ↑ Kontogiorgi, Elisabeth (2006). Population exchange in Greek Macedonia: the rural settlement of refugees 1922–1930. Oxford University Press. p. 200. ISBN 0-19-927896-2.

- ↑ John S. Koliopoulos (1999). Plundered loyalties: Axis occupation and civil strife in Greek West Macedonia, 1941–1949. C. Hurst & Co. p. 108. ISBN 1-85065-381-X.

- ↑ Clogg, Richard (2002). Minorities in Greece: aspects of a plural society. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 142. ISBN 1-85065-706-8.

- ↑ Danforth, Loring M. (1997). The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World. Princeton University Press. p. 116. ISBN 0-691-04356-6.

- ↑ ‘The matter is certainly more complex here, as the majority of the Greek citizens who grew up in what is usually called "Slavophone" or "bilingual" families have today a Greek national identity, as a result of either conscientious choice or coercion of their ancestors, in the first half of the twentieth century. A second group is made up of those who seem to reject any national identity (Greek or Macedonian) but have distinct ethnic identity, which they may call "indigenous" – dopia –, Slavomacedonian, or Macedonian. The smallest group is made up of those who have a clear Macedonian national identity and consider themselves as part of the same nation with the dominant one in the neighboring Republic of Macedonia.’ See: Greek Helsinki Monitor, Report about Compliance with the Principles of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (along guidelines for state reports according to Article 25.1 of the Convention), 18 September 1999, Part I, .

- ↑ Cowan, Jane K. (2000). Macedonia: the politics of identity and difference. Pluto Press. p. 102. ISBN 0-7453-1589-5.

- ↑ ‘Apart from certain peripheral areas in the far east of Greek Macedonia, which in our opinion must be considered as part of the Bulgarian linguistic area, the dialects of the Slav minority in Greece belong to Macedonia diasystem…’ See: Trudgill P., 2000, "Greece and European Turkey: From Religious to Linguistic Identity". In: Stephen Barbour and Cathie Carmichael (eds.), Language and Nationalism in Europe, Oxford : Oxford University Press, p.259.

- ↑ Loring M. Danforth (March 1997). The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World. Princeton University Press. pp. 37–. ISBN 978-0-691-04356-2. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

...that includes all of Greek Macedonia, which they insist on calling "Aegean Macedonia," a name which itself constitutes a challenge to the legitimacy of Greek sovereignty over the area. In addition ..