| Buchnera aphidicola | |

|---|---|

| |

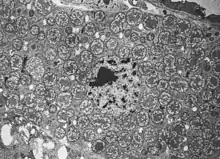

| Buchnera aphidicola in a host cell | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Pseudomonadota |

| Class: | Gammaproteobacteria |

| Order: | Enterobacterales |

| Family: | Erwiniaceae |

| Genus: | Buchnera Munson et al. 1991 |

| Species: | B. aphidicola |

| Binomial name | |

| Buchnera aphidicola Munson et al. 1991[1] | |

Buchnera aphidicola, a member of the Pseudomonadota and the only species in the genus Buchnera, is the primary endosymbiont of aphids, and has been studied in the pea aphid, Acyrthosiphon pisum.[2] Buchnera is believed to have had a free-living, Gram-negative ancestor similar to a modern Enterobacterales, such as Escherichia coli. Buchnera is 3 µm in diameter and has some of the key characteristics of its Enterobacterales relatives, such as a Gram-negative cell wall. However, unlike most other Gram-negative bacteria, Buchnera lacks the genes to produce lipopolysaccharides for its outer membrane. The long association with aphids and the limitation of crossover events due to strictly vertical transmission has seen the deletion of genes required for anaerobic respiration, the synthesis of amino sugars, fatty acids, phospholipids, and complex carbohydrates.[3] This has resulted not only in one of the smallest known genomes of any living organism, but also one of the most genetically stable.[3]

The symbiotic relationship with aphids began between 160 million and 280 million years ago,[4] and has persisted through maternal transmission and cospeciation. Aphids have developed a bilobed bacteriome containing sixty to eighty bacteriocyte cells in which the life cycle of Buchnera associated with aphids is confined to.[5] A mature aphid may carry an estimated 5.6 × 106 Buchnera cells. Buchnera has lost regulatory factors, allowing continuous overproduction of tryptophan and other amino acids. Each bacteriocyte contains multiple vesicles, symbiosomes derived from the cell membrane.

Genome

The sizes of various Buchnera genomes are in the range of 600 to 650 kb and encode on the order of 500 to 560 proteins. Many contain also one or two plasmids (2.3 to 11 kb in size).[6]

As with many endosymbionts, Abbot and Moran 2002 find Buchnera in Pemphigus obesinymphae to be undergoing relatively high genetic drift (i.e., relative to all organisms). This is evidenced by extremely low gene polymorphism and some nonsynonymous variants.[7]

Buchnera and plant viruses

Buchnera also increases the transmission of plant viruses by producing symbionin, a protein that binds to the viral coat and protects it inside the aphid. This makes it more likely that the virion will survive and be able to infect another plant when the aphid next feeds.[4]

History

Buchnera was named after Paul Buchner by Paul Baumann and his graduate student, and the first molecular characterization of a symbiotic bacterium was carried out by Baumann, using Buchnera. The initial studies on Buchnera later led to studies on symbionts of many groups of insects, pursued by numerous investigators, including Paul and Linda Baumann, Nancy Moran, Serap Aksoy, and Roy Gross, who together investigated symbionts of aphids, tsetse flies, ants, leafhoppers, mealybugs, whiteflies, psyllids, and others.

References

- ↑ "Buchnera". List of Prokaryotic names with Standing in Nomenclature. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ↑ Douglas, A. E. (January 1998). "Nutritional Interactions in Insect-Microbial Symbioses: Aphids and Their Symbiotic Bacteria Buchnera". Annual Review of Entomology. 43 (1): 17–37. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.43.1.17. ISSN 0066-4170. PMID 15012383.

- 1 2 Gil, Rosario; Sabater-Muñoz, Beatriz; Latorre, Amparo; Silva, Francisco J.; Moya, Andrés (2002). "Extreme Genome Reduction in Buchnera spp.: Toward the Minimal Genome Needed for Symbiotic Life". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (7): 4454–4458. doi:10.1073/pnas.062067299. ISSN 0027-8424. JSTOR 3058325. PMC 123669. PMID 11904373.

- 1 2 Banerjee, S; Hess, D; Majumder, P; Roy, D; Das, S (2004). "The Interactions of Allium sativum Leaf Agglutinin with a Chaperonin Group of Unique Receptor Protein Isolated from a Bacterial Endosymbiont of the Mustard Aphid". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (22): 23782–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M401405200. PMID 15028723.

- ↑ Baumann, Paul (October 2005). "Biology of Bacteriocyte-Associated Endosymbionts of Plant Sap-Sucking Insects". Annual Review of Microbiology. 59 (1): 155–189. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.59.030804.121041. ISSN 0066-4227. PMID 16153167.

- ↑ van Ham, Roeland C. H. J.; Kamerbeek, Judith; Palacios, Carmen; Rausell, Carolina; Abascal, Federico; Bastolla, Ugo; Fernández, Jose M.; Jiménez, Luis; Postigo, Marina (2003-01-21). "Reductive genome evolution in Buchnera aphidicola". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 100 (2): 581–586. doi:10.1073/pnas.0235981100. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 141039. PMID 12522265.

- ↑ Kirchberger, Paul C.; Schmidt, Marian L.; Ochman, Howard (2020-09-08). "The Ingenuity of Bacterial Genomes". Annual Review of Microbiology. Annual Reviews. 74 (1): 815–834. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-020518-115822. ISSN 0066-4227.

- Pérez-Brocal V, Gil R, Ramos S, Lamelas A, Postigo M, Michelena J, Silva F, Moya A, Latorre A (2006). "A small microbial genome: the end of a long symbiotic relationship?". Science. 314 (5797): 312–3. doi:10.1126/science.1130441. PMID 17038625. S2CID 40081627.

- Douglas, A E (1998). "Nutritional interactions in insect-microbial symbioses: Aphids and their symbiotic bacteria Buchnera". Annual Review of Entomology. 43: 17–38. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.43.1.17. ISSN 0066-4170. PMID 15012383.