| Bohemond II | |

|---|---|

Bohemond II of Antioch | |

| Prince of Antioch | |

| Reign | 1111 or 1119–1130 |

| Predecessor | Bohemond I or Roger of Salerno |

| Successor | Constance |

| Regent | Tancred of Hauteville (?) Roger of Salerno (?) Baldwin II of Jerusalem |

| Prince of Taranto | |

| Reign | 1111–1128 |

| Predecessor | Bohemond I |

| Regent | Constance of France |

| Born | 1107 or 1108 |

| Died | February 1130 (aged 22–23) |

| Spouse | Alice of Jerusalem |

| Issue | Constance of Antioch |

| House | Hauteville |

| Father | Bohemond I of Antioch |

| Mother | Constance of France |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

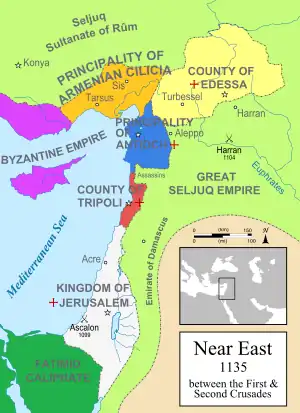

Bohemond II (1107/1108 – February 1130) was Prince of Taranto from 1111 to 1128 and Prince of Antioch from 1111/1119 to 1130. He was the son of Bohemond I, who in 1108 was forced to submit to the authority of the Byzantine Empire in the Treaty of Devol. Three years later, the infant Bohemond inherited the Principality of Taranto under the guardianship of his mother, Constance of France. The Principality of Antioch was administered by his father's nephew, Tancred, until 1111. Tancred's cousin, Roger of Salerno, managed the principality from 1111 to 1119. After Roger died in the Battle of the Field of Blood, Baldwin II of Jerusalem took over the administration of Antioch. However, he did acknowledge Bohemond's right to personally rule the principality upon reaching the age of majority.

Bohemond came to Antioch in autumn 1126. He launched successful military campaigns against the nearby Muslim rulers, but his conflict with Joscelin I of Courtenay enabled Imad ad-Din Zengi to secure Mosul and Aleppo. Meanwhile, Roger II of Sicily occupied the Principality of Taranto in 1128. Bohemond died fighting against Danishmend Emir Gazi during a military campaign against Cilician Armenia, and Gümüshtigin sent Bohemond's embalmed head to the Abbasid Caliph.

Early life

Bohemond II was the son of Prince Bohemond I of Taranto and Antioch and Constance of France.[1] He was born in 1107 or 1108.[2][3] In 1104, Bohemond I returned to Europe to seek military assistance against the Byzantine Empire and left his nephew Tancred in Syria to administer Antioch.[4] Two charters show that Tancred styled himself prince of Antioch in 1108.[5] In September of that year, Bohemond I was forced to sign the Treaty of Devol, which authorized the Byzantine Empire to annex Antioch upon his death.[6]

Bohemond I died in Apulia in 1111. Bohemond II was still a minor,[7] so his mother took charge of the government of Taranto.[8] The Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos sent envoys to Tancred to demand control of Antioch, but Tancred refused to obey and continued to govern the principality.[9] Tancred died in 1112 and bequeathed Antioch to his nephew, Roger of Salerno.[10][11]

Roger's legal status during his rule in Antioch is uncertain.[12] According to William of Tyre, Tancred made Roger his successor "with the understanding that, at the demand of Bohemond or his heirs, he should not refuse to return it," suggesting that Roger was simply regent for the child Bohemond.[13] Roger adopted the title of prince, which implies that he regarded himself the ruler of Antioch in his own right.[12][14] The contemporaneous Fulcher of Chartres accused Roger of depriving of "his inheritance his own lord, the son of Bohemond [I], then living in Apulia with his mother."[15] Charters issued in Bohemond's Italian domains between 1117 and 1119 emphasized that he was the son of the prince of Antioch, but did not style him prince.[16]

After Roger and most Antiochene noblemen perished in the Battle of the Field of Blood on 28 June 1119, King Baldwin II of Jerusalem hurried to Syria to save Antioch from Ilghazi, the Artuqid ruler of Mardin.[17][18] The notables of Antioch proclaimed Baldwin ruler of Antioch, but they emphasized that Antioch was Bohemond's "rightful inheritance," according to Walter the Chancellor.[15][19] Baldwin promised to cede Antioch to Bohemond if Bohemond came to the principality.[15] Those who were present at the meeting agreed that Bohemond should marry Baldwin's daughter, Alice.[19][20] They also decreed that Bohemond would not be entitled to reclaim grants made during his absence from the principality.[20]

Baldwin II was captured in 1123,[21] and the burghers of Antioch sent envoys to Bohemond, urging him to come to his principality.[22] Bohemond reached the age of majority at the age of 16.[2] According to William of Tyre, he made an agreement with Duke William II of Apulia, stipulating that the one who first died without issue was to will his principality to the other; however, the reliability of William's report is suspect.[23][24] Alexander of Telese recorded that before leaving for Syria, Bohemond entrusted his Italian domains to the Holy See, but Romuald of Salerno said that he made Alexander, Count of Conversano, the overseer of those lands.[23][25] Bohemond sailed from Otranto with a fleet of twenty-four ships in September 1126.[26]

Prince of Antioch

Bohemond landed at the port of St. Symeon in the Principality of Antioch in October or November.[20][22] He went to Antioch to meet Baldwin II of Jerusalem, who subsequently ceded Antioch to him.[26] Bohemond was officially installed as prince in Baldwin's presence.[27]

Matthew of Edessa portrayed Bohemond as "a forceful character and great power."[27] Badr ad-Daulah captured Kafartab shortly after Bohemond's arrival, but Bohemond quickly recaptured the fortress in early 1127.[26][27] According to historian Steven Runciman, Bohemond's attack against the Munqidhites of Shaizar, which was recorded by Usama ibn Munqidh, also occurred during this period.[26][27]

Bohemond came into conflict with Joscelin I of Edessa in 1127,[28][22] although sources do not reveal the reason behind the enmity of the two Christian rulers.[28] According to Runciman, Joscelin seized former Antiochene territories from Il-Bursuqi, governor of Mosul. Furthermore, Bohemond refused to cede Azaz to Joscelin, despite the fact that Roger of Salerno promised it to Joscelin as the dowry of his second wife, Maria of Salerno.[29] Taking advantage of Bohemond's absence due to a campaign, Joscelin invaded Antioch with the assistance of Turkish mercenaries, plundering the villages along the frontier.[29]

Bernard of Valence, Latin Patriarch of Antioch, imposed an interdict on the County of Edessa.[29] Baldwin II of Jerusalem hurried to Syria to mediate between Bohemond and Joscelin in early 1128.[22][29] Joscelin, who had become seriously ill, agreed to restore the property to Bohemond and to do homage to him.[30] However, the conflict between Bohemond and Joscelin enabled Imad ad-Din Zengi, Il-Bursuqi's successor as governor of Mosul, to seize Aleppo without resistance on 28 June 1128.[31]

Meanwhile, Bohemond's cousin William II of Apulia had died without issue on 25 July 1127.[24] Pope Honorius II tried to prevent Count Roger II of Sicily (the cousin of both William and Bohemond) from seizing Apulia, but Roger did not obey him.[25] In May 1128, he invaded Bohemond's Italian principality,[25] capturing Taranto, Otranto and Brindisi without resistance.[25] He completed the conquest of the whole principality around 15 June.[25]

Taking advantage of the disputes between the Assassins and Taj al-Muluk Buri, atabeg of Damascus, Baldwin II of Jerusalem invaded Damascene territory and laid siege to Banias in November 1129.[32] Bohemond and Joscelin joined Baldwin, but a heavy rainfall forced the crusaders to abandon the siege.[32][28]

Bohemond decided to recover Anazarbus and other territories which had been lost to the Cilician Armenia.[33] He invaded Cilicia in February 1130, traveling along the Ceyhan River.[34] Leo I of Cilicia sought assistance from the Danishmend Emir Gazi who made a surprise attack on Bohemond's army.[35] Bohemond and his soldiers were massacred in the battle.[36][37] According to Michael the Syrian, the Turks killed Bohemond because they did not recognize him; had they recognized him, they would have saved him so they could demand a ransom from him.[38] Gümüshtigin had Bohemond's head embalmed and sent to Al-Mustarshid, the Abbasid caliph.[35]

Family

Bohemond's wife, Alice, was the second daughter of Baldwin II of Jerusalem and Morphia of Melitene.[39] Their only child, Constance, was two when Bohemond died in 1130.[40] Alice tried to secure the regency for Constance for herself, but the Antiochene noblemen preferred her father, Baldwin II of Jerusalem.[40] After Bohemond's death, Roger II of Sicily laid claim to Antioch, but he could never assert it against Constance.[41]

| Genealogy of the Norman rulers of Antioch and southern Italy[42] |

|---|

References

- ↑ Runciman 1989, p. 125, Appendix III (Genealogical tree No. 2.).

- 1 2 Houben 2002, p. 31.

- ↑ The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica (2016). "Bohemond II Prince of Antioch". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 3 May 2016.

- ↑ Barber 2012, p. 83.

- ↑ Asbridge 2000, p. 137.

- ↑ Asbridge 2000, pp. 137–138.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, p. 51.

- ↑ Norwich 1992, p. 304.

- ↑ Asbridge 2000, p. 138.

- ↑ Barber 2012, p. 103.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, p. 124.

- 1 2 Asbridge 2000, p. 139.

- ↑ Asbridge 2000, pp. 141–142.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, p. 126.

- 1 2 3 Asbridge 2000, p. 141.

- ↑ Asbridge 2000, p. 142.

- ↑ Barber 2012, pp. 123–124.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, pp. 149, 152.

- 1 2 Runciman 1989, p. 152.

- 1 2 3 Asbridge 2000, p. 146.

- ↑ Nicholson 1969, p. 419.

- 1 2 3 4 Nicholson 1969, p. 428.

- 1 2 Houben 2002, p. 43.

- 1 2 Norwich 1992, p. 307.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Norwich 1992, p. 312.

- 1 2 3 4 Runciman 1989, p. 176.

- 1 2 3 4 Asbridge 2000, p. 147.

- 1 2 3 Asbridge 2000, p. 127.

- 1 2 3 4 Runciman 1989, p. 181.

- ↑ Nicholson 1969, pp. 428–429.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, pp. 181–182.

- 1 2 Runciman 1989, p. 180.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, p. 182.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, pp. 182–183.

- 1 2 Runciman 1989, p. 183.

- ↑ Nicholson 1969, p. 431.

- ↑ Barber 2012, p. 152.

- ↑ Barber 2012, p. 395.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, p. 176, Appendix III (Genealogical tree No. 1.).

- 1 2 Runciman 1989, p. 184.

- ↑ Houben 2002, pp. 44, 78.

- ↑ Runciman 1989, Appendix III.

Sources

- Asbridge, Thomas (2000). The Creation of the Principality of Antioch, 1098–1130. Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-661-3.

- Barber, Malcolm (2012). The Crusader States. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11312-9.

- Houben, Hubert (2002). Roger II of Sicily: Ruler between East and West. Translated by Graham A. Loud and Diane Milburn. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-65208-1.

- Nicholson, Robert L. (1969). "The Growth of the Latin States, 1118–1144". In Setton, Kenneth M.; Baldwin, Marshall W. (eds.). A History of the Crusades, Volume I: The First Hundred Years. The University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 410–447. ISBN 0-299-04844-6.

- Norwich, John Julius (1992). The Normans in Sicily. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-015212-8.

- Runciman, Steven (1989). A History of the Crusades, Volume II: The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East, 1100–1187. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-06162-8.

Further reading

- Richard, Jean (1999). The Crusades: c. 1071-c. 1291. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62566-1.