The Lord Boothby | |

|---|---|

Boothby in 1924 | |

| Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Food | |

| In office 15 May 1940 – 22 October 1940 | |

| Monarch | George VI |

| Prime Minister | Winston Churchill |

| Preceded by | Alan Lennox-Boyd |

| Succeeded by | Gwilym Lloyd George |

| Member of the House of Lords Lord Temporal | |

| In office 18 August 1958 – 16 July 1986 Life Peerage | |

| Member of Parliament | |

| In office 29 October 1924 – 18 August 1958 | |

| Preceded by | Frederick Martin |

| Succeeded by | Patrick Wolrige-Gordon |

| Constituency | Aberdeen and Kincardine East (1924–1950) East Aberdeenshire (1950–1958) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 12 February 1900 Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Died | 16 July 1986 (aged 86) London, England |

| Political party | Conservative |

| Spouses | Diana Cavendish

(m. 1935; div. 1937)Wanda Sanna (m. 1967) |

| Parent(s) | Robert Tuite Boothby Mabel Lancaster |

| Alma mater | Eton College Magdalen College, Oxford |

Robert John Graham Boothby, Baron Boothby, KBE (12 February 1900 – 16 July 1986), often known as Bob Boothby, was a British Conservative politician.

Early life

The only son of Sir Robert Tuite Boothby, KBE, of Edinburgh and a cousin of Rosalind Grant, mother of the broadcaster Sir Ludovic Kennedy, Boothby was educated at St Aubyns School, Eton College, and Magdalen College, Oxford. Before going up to Oxford, near the end of the First World War, he trained as an officer and was commissioned into the Brigade of Guards, but was too young to see active service.[1] Boothby read History at the University of Oxford; the shortened war course was not classed, being marked either 'Pass' or 'Fail'. He attended a few lectures and did some general reading, but, as he cheerfully observed, "there were far too many other things to do".[2] He achieved a pass without distinction in 1921.[3] After Oxford, he became a partner in a firm of stockbrokers.

Politics

Boothby was an unsuccessful parliamentary candidate for Orkney and Shetland in 1923 and was elected as Member of Parliament (MP) for Aberdeen and Kincardine East in 1924. He held the seat until its abolition in 1950, when he was elected for its successor constituency of East Aberdeenshire. Re-elected a final time in 1955, he gave up the seat in 1958 when he was raised to the peerage, triggering a by-election.

Boothby was Parliamentary Private Secretary to Chancellor of the Exchequer Winston Churchill from 1926 to 1929. He helped launch the Popular Front in December 1936.[4] He held junior ministerial office as Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Food in 1940–41. He was later forced to resign his post and go to the back benches for not declaring an interest when asking a parliamentary question. During the Second World War he joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve and served as a junior staff officer with Bomber Command, and later as a liaison officer with the Free French Forces, retiring with the rank of Flight Lieutenant. In 1950 he received the Legion of Honour for his latter services.[5]

In 1954 (echoing words he had said in 1934), Boothby complained that for 30 years he had been advocating "a constructive policy on broad lines" but that this had not been taken up: "The doctrine of infallibility has always applied to the Treasury and the Bank of England". Boothby opposed free trade in food stuffs, and claimed that such a policy would invalidate the Agriculture Act 1947 and ruin British farmers. This economic liberalism of the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Rab Butler, led to Boothby complaining that "The Tory Party have in fact become the Liberal Party" and cited what the leader of the Liberal Party (Clement Davies) had said to him about Butler: "Sir Robert Peel has come again."[6] In response, Davies claimed that Boothby "has been sitting on the wrong side of the House for many years. Undoubtedly he said tonight that he is the planner of planners. I do not believe in that kind of planning. The hon. Member seems to know better than the ordinary person what is good for the ordinary person, what he ought to buy, where he ought to buy it, where he ought to manufacture and everything else of that kind. There is the true Socialist".[6]

Boothby was a British delegate to the Consultative Assembly of the Council of Europe from 1949 until 1957 and advocated the United Kingdom's entry into the European Economic Community (a predecessor of the European Union). He was a prominent commentator on public affairs on radio and television, often taking part in the long-running BBC radio programme Any Questions. He also advocated the virtues of herring as a food.[7]

He was Vice-Chairman of the Committee on Economic Affairs, 1952–1956; Honorary President of the Scottish Chamber of Agriculture, 1934; Rector of the University of St Andrews, 1958–1961; Chairman of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, 1961–1963; and President, Anglo-Israel Association, 1962–1975. He was awarded an Honorary LLD by St Andrews in 1959, and was made an Honorary Burgess of the Burghs of Peterhead, Fraserburgh, Turriff and Rosehearty. He was appointed an Officer of the Legion of Honour in 1950, and a KBE in 1953.[8]

Boothby was raised to the peerage as a life peer with the title Baron Boothby, of Buchan and Rattray Head in the County of Aberdeen, on 22 August 1958.[9]

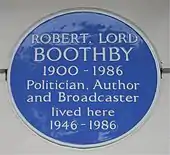

There is a blue plaque on his house in Eaton Square, London.

He was the subject of This Is Your Life in October 1963, when he was surprised by Eamonn Andrews at BBC Television Centre.

Homosexual law reform

During the 1950s, Boothby was a prominent advocate of decriminalizing homosexual acts between men. In his memoirs, he wrote that he was determined to "do something practical to remove the fear and misery in which many of our most gifted citizens were then compelled to live".[10]

In December 1953, he sent a memorandum to David Maxwell Fyfe, then the Home Secretary, calling for the establishment of a departmental inquiry into homosexuality. He argued that:

By attaching so fearful a stigma to homosexuality as such, you put a very large number of otherwise law-abiding and useful citizens on the other side of the fence which divides the good citizen from the bad. By making them feel that, instead of unfortunates they are social pariahs, you drive them into squalor – perhaps into crime; and produce that very "underground" which it is so clearly in the public interest to eradicate.[11]

Boothby premised his argument for law reform on the idea that it was the role of the state "not to punish psychological disorders – rather to try and cure them".[11] He argued in the House of Commons that the law as it was did not "achieve the objective of all of us, which is to limit the incidence of homosexuality and to mitigate its evil effects".[12]

After the Departmental Committee on Homosexual Offences and Prostitution recommended decriminalization in the Wolfenden Report of 1957, Boothby claimed that, through his correspondence with Fyfe, he had been "primarily responsible" for the committee's establishment.[13]

Personal life

Boothby had a colourful, if reasonably discreet, private life, mainly because the press refused to print what they knew of him, or were prevented from doing so. Woodrow Wyatt, whose reliability has been questioned,[14][15][16] claimed after the death of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother that she had confided to him in an interview in 1991 that "The press knew all about it", referring to Boothby's affairs, and that she had described Boothby as "a bounder but not a cad".[17]

From 1930, Boothby had a long affair with Lady Dorothy Macmillan, wife of the Conservative politician Harold Macmillan (prime minister from 1957 to 1963). He was rumoured to be the father of the youngest Macmillan daughter, Sarah, although the 2010 biography of Harold Macmillan by D. R. Thorpe discounts Boothby's paternity.[17][18][19] This connection to Macmillan, via his wife, has been seen as one of the reasons why the police did not investigate the death of Edward Cavendish, 10th Duke of Devonshire, who died in the presence of suspected serial killer John Bodkin Adams.[17] The duke was Lady Dorothy's brother, and it is thought the police were wary of drawing press attention to her while she was being unfaithful.[17]

Boothby was married twice. His first wife (married 1935) was Diana Cavendish, daughter of Lord Richard Cavendish, and Lady Dorothy's first cousin; Boothby married her after concluding his relationship with the married Lady Dorothy to be "on the wane". He swiftly realised the marriage had been a mistake (it went on to be a source of long-lasting guilt feelings for him) and it was dissolved in 1937.[20] Lady Dorothy died in 1966. The following year Boothby married Wanda Sanna, a Sardinian woman 33 years his junior. His second cousin, writer and broadcaster Sir Ludovic Kennedy, asserted that Boothby fathered at least three children by the wives of other men ("two by one woman, one by another").[21]

Sexuality and the Kray twins

Partly because of his support for homosexual law reform, Boothby was subject to public rumours about his sexuality, although he insisted publicly in 1954 that he was "not a homosexual".[22] He did, however, comment that "sub-conscious bi-sexuality is a component part of all of us [and] the majority of males pass through a homosexual period".[23] While an undergraduate at Magdalen College, Oxford, Boothby earned the nickname 'the Palladium', because "he was twice nightly".[24] He later spoke about the role of a speculated homosexual relationship in the drowning of his friend Michael Llewelyn Davies (one of the models for Peter Pan) and fellow Oxonian Rupert Buxton.[25] In a Channel 4 documentary broadcast in 1997, it was claimed that he did not begin to have physical relationships with women until the age of 25.[24]

In 1963, Boothby began an affair with East End cat burglar Leslie Holt (d. 1979), a younger man he met at a gambling club. Holt introduced him to the gangster Ronnie Kray, one of the Kray twins, who allegedly supplied Boothby with young men, and arranged orgies in Cedra Court (the apartment block in Hackney where the Kray twins lived), receiving favours from Boothby in return.[24] When Boothby's underworld associations came to the attention of the Sunday Express, the Conservative-supporting newspaper opted not to publish the damaging story.[26][27] The matter was eventually reported in 1964 in the Labour-supporting Sunday Mirror tabloid, and the parties were subsequently named by the German magazine Stern.[28]

Boothby denied the story and threatened to sue the Mirror. His close friend Tom Driberg—a senior Labour MP, and also homosexual—also associated with the Krays; hence, neither of the major political parties had an interest in publicity, and the newspaper's owner Cecil King came under pressure from the Labour leadership to drop the matter.[24] The Mirror backed down, sacked its editor, apologised and paid Boothby £40,000 in an out-of-court settlement. Other newspapers became less willing to cover the Krays' criminal activities, which continued for three more years.[24] The police investigation received no support from Scotland Yard, while Boothby embarrassed his fellow peers by campaigning on behalf of the Krays in the Lords, until their increasing violence made association impossible.[24] It has been claimed that journalists who investigated Boothby were subjected to legal threats and break-ins, and that much of that suppression was directed by Arnold Goodman. Documents released in 2015 show that MI5 used the Kray twins to gather intelligence on homosexual politicians and establishment figures.

The MI5 files focus on Lord Boothby, who was said to share Ronnie Kray's fondness for young men.

Meeting with Hitler

Boothby was a frequent visitor to Weimar Germany, and in 1932, he was invited to meet Hitler. In his autobiography, he recalls that Hitler "sprang to his feet, lifted his right arm, and shouted 'Hitler!'; ... I responded by clicking my heels together, raising my right arm, and shouting back: 'Boothby!'" Unlike some who were impressed by Hitler, Boothby came away thinking he had seen "the unmistakable glint of madness in his eyes," and the meeting helped convince him to become one of Churchill's small group of parliamentary campaigners for faster rearmament.[29]

Death

After his death from a heart attack in Westminster Hospital, London, aged 86, Boothby's ashes were scattered at Rattray Head near Crimond, Aberdeenshire, off the coast of his former constituency.[30]

Arms

|

|

References

- ↑ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 6. Oxford University Press. 2004. p. 639. ISBN 0-19-861356-3.Article by John Grigg.

- ↑ Robert Rhodes James, Robert Boothby: A Portrait of Churchill's Ally, Harmondsworth: Viking Penguin, 1991, pp. 38–39

- ↑ Oxford University Calendar 1925, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1925, p. 229

- ↑ The Liberal Party and the Popular Front, English Historical Review (2006)

- ↑ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 6. p. 640.

- 1 2 COMMONWEALTH ECONOMIC CONFERENCE HC Deb 04 February 1954 vol 523 cc576-695

- ↑ Referred to in passing during Face to Face, BBC Television, 27 May 1959.

- ↑ "No. 39863". The London Gazette (Supplement). 1 June 1953. p. 2953.

- ↑ "No. 41479". The London Gazette. 22 August 1958. p. 5211.

- ↑ Boothby, Robert (1978). Boothby: Recollections of a Rebel. London: Hutchinson of London. p. 25. ISBN 978-0091348304.

- 1 2 Boothby, Robert. "Robert Boothby memorandum to David Maxwell Fyfe, copied to Viscount Hailsham" (7 December 1953) [Textual record]. The Papers of Lord Hailsham, Series: 2, Political correspondence, Box: 25, 1952–1954, File: 7, Correspondence with Members of Parliament. Cambridge: Churchill Archives Centre, University of Cambridge.

- ↑ HANSARD 1803–2005; HC Deb 28 April 1954, vol. 526, c1750.

- ↑ Boothby, Robert (30 November 1958). "Lord Boothby's Column". Sunday Dispatch.

- ↑ David Sexton, "Don't believe all those diary droolings", Evening Standard (12 October 1998), A 11: "Robert Rhodes James, the editor of Chips Channon's entertaining diaries, advised caution in believing them. 'Even if the diarist is not attempting to give a deliberately false version, a talented writer can easily over-dramatise...' There is plenty of internal evidence that Wyatt should be approached with a similar caution."

- ↑ Stephen Lomax, Valentine Low, "Did he drool? What a horrible thought", Evening Standard (19 October 1998), p. 15.

- ↑ Petronella Wyatt, "All of a tremble", The Spectator (31 October 1998), p. 71.

- 1 2 3 4 Cullen, Pamela V., A Stranger in Blood: The Case Files on Dr John Bodkin Adams, London, Elliott & Thompson, 2006, ISBN 1-904027-19-9 pp. 617–18

- ↑ D. R. Thorpe, Supermac: The Life of Harold Macmillan (London: Pimlico, paperback edition, 2011, p. 100. London: Chatto & Windus, Kindle ed., 2010, locs. 2467, 2477).

- ↑ "Too Obviously Cleverer". London Review of Books. 8 September 2011.

- ↑ Angela Lambert (23 February 1994). "The Prime Minister, his wife and her lover: Dorothy Macmillan had an affair that lasted 30 years. Everyone knew but nobody talked. How times have changed, says Angela Lambert". The Independent. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ↑ Matthew Parris and Kevin Maguire, Great Parliamentary Scandals: Five Centuries of Calumny, Smear and Innuendo, Robson Books, 2004, p116

- ↑ "The Subject of Rumours". The Times. 1 August 1964.

- ↑ Robert Rhodes James, Bob Boothby: A Portrait (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1991), p. 40.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Lords of the Underworld", Secret History, Channel 4 (23 June 1997).

- ↑ "Rupert Buxton". Neverpedia: The Peter Pan resource. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- ↑ David Barrett "Letters shed new light on Kray twins scandal", The Sunday Telegraph, 26 July 2009

- ↑ "Reggie Kray: Notorious gangster", BBC News, 1 October 2000

- ↑ "The Kray Twins: Brothers in Arms" on truTV

- ↑ Boothby, Robert (1978). Boothby: Recollections of a Rebel. London: Hutchinson. p. 110. ISBN 978-0091348304.

- ↑ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 6. p. 641.

- ↑ Burke's Peerage. 1959.

Publications

- The New Economy, London: Secker & Warburg, 1943

- I Fight to Live: Autobiography, London: Victor Gollancz, 1947

- My Yesterday, Your Tomorrow, London: Hutchinson, 1962

- Boothby: Recollections of a Rebel, London: Hutchinson, 1978