| Black Hawk War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Indian Wars | |||||||

Black Hawk, the Sauk war chief and namesake of the Black Hawk War in 1832 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Ho-Chunk Menominee Dakota and Potawatomi allies | Black Hawk's British Band with Ho-Chunk and Potawatomi allies | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Henry Atkinson Edmund P. Gaines Henry Dodge Isaiah Stillman Jefferson Davis Winfield Scott Robert C. Buchanan |

Black Hawk Neapope Wabokieshiek | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

6,000+ militiamen 630 Army regulars 700+ Native Americans[1] |

500 warriors 600 non-combatants | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 77 killed (including non-combatants)[2] | 450–600 killed (including non-combatants)[2][3] | ||||||

The Black Hawk War was a conflict between the United States and Native Americans led by Black Hawk, a Sauk leader. The war erupted after Black Hawk and a group of Sauks, Meskwakis (Fox), and Kickapoos, known as the "British Band", crossed the Mississippi River, to the U.S. state of Illinois, from Iowa Indian Territory in April 1832. Black Hawk's motives were ambiguous, but he was apparently hoping to reclaim land that was taken over by the United States in the disputed 1804 Treaty of St. Louis.

U.S. officials, convinced that the British Band was hostile, mobilized a frontier militia and opened fire on a delegation from the Native Americans on May 14, 1832. Black Hawk responded by successfully attacking the militia at the Battle of Stillman's Run. He led his band to a secure location in what is now southern Wisconsin and was pursued by U.S. forces. Meanwhile, other Native Americans conducted raids against forts and colonies largely unprotected with the absence of the militia. Some Ho-Chunk and Potawatomi warriors took part in these raids, although most tribe members tried to avoid the conflict. The Menominee and Dakota tribes, already at odds with the Sauks and Meskwakis, supported the United States.

Commanded by General Henry Atkinson, the U.S. forces tracked the British Band. Militia under Colonel Henry Dodge caught up with the British Band on July 21 and defeated them at the Battle of Wisconsin Heights. Black Hawk's band was weakened by hunger, death, and desertion, and many native survivors retreated towards the Mississippi. On August 2, U.S. soldiers attacked the remnants of the British Band at the Battle of Bad Axe, killing many and capturing most who remained alive. Black Hawk and other leaders escaped, but later surrendered and were imprisoned for a year.

The Black Hawk War gave Abraham Lincoln his brief military service, although he saw no combat.[4] Other participants who would later become famous included Winfield Scott, Zachary Taylor, Jefferson Davis and James Clyman. The war gave impetus to the U.S. policy of Indian removal, in which Native American tribes were pressured to sell their lands and move west of the Mississippi River to reside.

Background

In the 18th century, the Sauk and Meskwaki (or Fox) Native American tribes lived along the Mississippi River in what are now the U.S. states of Illinois and Iowa. The land they lived on was considered sacred because of the fertile soil, prime hunting, accessibility to lead, and access to water, which was helpful for trade. The two tribes had become closely connected after having been displaced from the Great Lakes region in conflicts with New France and other Native American tribes, particularly after the so-called Fox Wars ended in the 1730s.[5] By the time of the Black Hawk War, the population of the two tribes was about 6,000 people.[6]

Disputed treaty

As the United States colonized westward in the early 19th century, government officials sought to buy as much Native American land as possible. In 1804, territorial governor William Henry Harrison negotiated a treaty in St. Louis in which a group of Sauk and Meskwaki leaders supposedly sold their lands east of the Mississippi for more than $2,200, in goods and annual payments of $1,000 in goods. The treaty became controversial because the Native leaders had not been authorized by their tribal councils to cede lands. Historian Robert Owens argued that the chiefs probably did not intend to give up ownership of the land, and that they would not have sold so much valuable territory for such a modest price.[7] Historian Patrick Jung concluded that the Sauk and Meskwaki chiefs intended to cede a little land, but that the Americans included more territory in the treaty's language than the Natives realized.[8] According to Jung, the Sauks and Maskwacis did not learn the true extent of the cession until years later.[9]

The 1804 treaty allowed the tribes to continue using the ceded land until it was sold to American colonists by the U.S. government.[10] For the next two decades, Sauks continued to live at Saukenuk, their primary village, which was located near the confluence of the Mississippi and Rock Rivers.[11] In 1828, the U.S. government finally began to have the ceded land surveyed for colonists. Indian agent Thomas Forsyth informed the Sauks that they should vacate Saukenuk and their other settlements east of the Mississippi.[12]

Sauks divided

The Sauks were divided about whether to resist implementation of the disputed 1804 treaty.[13] Most Sauks decided to relocate west of the Mississippi rather than become involved in a confrontation with the United States. The leader of this group was Keokuk, who had helped defend Saukenuk against the Americans during the War of 1812. Keokuk was not a chief, but as a skilled orator, he often spoke on behalf of the Sauk civil chiefs in negotiations with the Americans.[14] Keokuk regarded the 1804 treaty as a fraud, but after having seen the size of American cities on the east coast in 1824, he did not think the Sauks could successfully oppose the United States.[15]

The Americans knew Keokuk was for peace and would not wage war against them. For this reason, the Americans gave him many gifts, hoping to bribe Keokuk into moving across the Mississippi into Iowa. The American plan succeeded when Keokuk and a majority of the tribe decided to leave. However, about 800 Sauks—roughly one-sixth of the tribe—chose instead to resist American expansion.[16] Black Hawk, a war captain who had fought against the United States in the War of 1812 and was now in his 60s, emerged as the leader of this faction in 1829.[17] Like Keokuk, Black Hawk was not a civil chief, but he became Keokuk's primary rival for influence within the tribe. Black Hawk had actually signed a treaty in May 1816 that affirmed the disputed 1804 land cession, but he insisted that what had been written down was different from what had been spoken at the treaty conference. According to Black Hawk, the "whites were in the habit of saying one thing to the Indians and putting another thing down on paper."[18]

Black Hawk was determined to hold onto Saukenuk, a village at the confluence of the Rock River with the Mississippi, where he lived and had been born. When the Sauks returned to the village in 1829 after their annual winter hunt in the west, they found that it had been occupied by squatters who were anticipating the sale of land.[19] After months of clashes with the squatters, the Sauks left in September 1829 for the next winter hunt. Hoping to avoid further confrontations, Keokuk told Forsyth that he and his followers would not return to Saukenuk.[20]

Against the advice of Keokuk and Forsyth, Black Hawk's faction returned to Saukenuk in the spring of 1830.[21] This time, they were joined by more than 200 Kickapoos, a people who had often allied with the Sauks.[22] Black Hawk and his followers became known as the "British Band" because they sometimes flew a British flag to defy claims of U.S. sovereignty, and because they hoped to gain the support of the British at Fort Malden in Canada.[23]

When the British Band once again returned to Saukenuk in 1831, Black Hawk's following had grown to about 1,500 people, and now included some Potawatomis,[24] a people with close ties to the Sauks and Meskwakis.[25] American officials determined to force the British Band out of the state. General Edmund P. Gaines, commander of the Western Department of the United States Army, assembled troops with the hope of intimidating Black Hawk into leaving. The army had no cavalry to pursue the Sauks should they flee further into Illinois on horseback, and so on June 5 Gaines requested that the state militia provide a mounted battalion.[26] Illinois governor John Reynolds had already alerted the militia; about 1,500 volunteers turned out.[27] Meanwhile, Keokuk convinced many of Black Hawk's followers to leave Illinois.[28]

On June 25, 1831, Gaines sent troops to Vandruff Island across from Saukenuk. The island had been named for a farmer and trader who operated a ferry, as well as sold liquor to the natives, which had previously prompted a raid by Black Hawk to destroy the whiskey.[29] This time, underbrush had grown to impede the militiamen from landing, so the next day the militia tried to assault Saukenuk itself, only to find that Black Hawk and his followers had abandoned the village and recrossed the Mississippi.[30] On June 30, Black Hawk, Quashquame, and other Sauk leaders met with Gaines and signed an agreement in which the Sauks promised to remain west of the Mississippi and to break off further contact with the British in Canada.[31]

Black Hawk's return

In late 1831, Neapope, a Sauk civil chief, returned from Fort Malden and told Black Hawk that the British and the other Illinois tribes were prepared to support the Sauks against the United States. Why Neapope made these claims, which would prove to be unfounded, is unclear. Historians have described Neapope's report to Black Hawk as "wishful thinking"[32] and the product of a "fertile imagination".[33] Black Hawk welcomed the information, though he would later criticize Neapope for misleading him. He spent the winter in an unsuccessful attempt to recruit additional allies from other tribes and from Keokuk's followers.[34]

According to Neapope's erroneous report, Wabokieshiek ("White Cloud"), a shaman known to Americans as the "Winnebago Prophet", had claimed that other tribes were ready to support Black Hawk.[33] Wabokieshiek's mother was a Ho-Chunk (Winnebago), but his father had belonged to a Sauk clan that provided the tribe's civil leaders. When Wabokieshiek joined the British Band in 1832, he would become the ranking Sauk civil chief in the group.[35] His village, Prophetstown, was about thirty-five miles up the Rock River from Saukenuk.[36] The village was inhabited by about 200[16] Ho-Chunks, Sauks, Meskwakis, Kickapoos, and Potawatomis who were dissatisfied with tribal leaders who refused to stand up to American expansion.[37] Although some Americans would later characterize Wabokieshiek as a primary instigator of the Black Hawk War, the Winnebago Prophet, according to historian John Hall, "actually discouraged his followers from resorting to armed conflict with the whites".[38]

On April 5, 1832, the British Band entered Illinois once again.[39] Numbering about 500 warriors and 600 non-combatants, they crossed near the mouth of the Iowa River over to Yellow Banks (present-day Oquawka, Illinois), and then headed north.[40] Black Hawk's intentions upon reentering Illinois are not entirely clear, since reports from both colonists and Indian sources are conflicting. Some said that the British Band intended to reoccupy Saukenuk, while others said that the destination was Prophetstown.[41] According to historian Kerry Trask, "even Black Hawk may not have been sure where they were going and what they intended to do".[42]

As the British Band moved into Illinois, American officials urged Wabokieshiek to advise Black Hawk to turn back. Previously, the Winnebago Prophet had encouraged Black Hawk to come to Prophetstown, arguing that the 1831 agreement made with General Gaines prohibited a return to Saukenuk, but did not forbid the Sauks from moving to Prophetstown.[43] Now, instead of telling Black Hawk to turn back, Wabokieshiek told him that, as long as the British Band remained peaceful, the Americans would have no choice but to let them settle at Prophetstown, especially if the British and the area tribes supported the band.[44] Although the British Band traveled with armed guards as a security precaution, Black Hawk was probably hoping to avoid a war when he reentered Illinois. The presence of women, children, and the elderly indicated that the band was not a war party.[45]

Intertribal war and American policy

Although the return of Black Hawk's band worried U.S. officials, they were at the time more concerned about the possibility of a war among the Native American tribes in the region.[46] Most accounts of the Black Hawk War focus on the conflict between Black Hawk and the United States, but historian John Hall argues that this overlooks the perspective of many Native American participants. According to Hall, "the Black Hawk War also involved an intertribal conflict that had smoldered for decades".[47] Tribes along the Upper Mississippi had long fought for control of diminishing hunting grounds, and the Black Hawk War provided an opportunity for some Natives to resume a war that had nothing to do with Black Hawk.[48]

After having displaced the British as the dominant outside power following the War of 1812, the United States had assumed the role of mediator in intertribal disputes. Before the Black Hawk War, U.S. policy discouraged intertribal warfare. This was not strictly for humanitarian reasons: intertribal warfare made it more difficult for the United States to acquire Indian land and move the tribes to the West, a policy known as Indian removal, which had become the primary goal by the late 1820s.[49] U.S. efforts at mediation included multi-tribal treaty councils at Prairie du Chien in 1825 and 1830, in which tribal boundaries were drawn.[50] Native Americans sometimes resented American mediation, especially young men, for whom warfare was an important avenue of social advancement.[51]

The situation was complicated by the American spoils system. After Andrew Jackson assumed the U.S. presidency in March 1829, many competent Indian agents were replaced by unqualified Jackson loyalists, argues historian John Hall. Men like Thomas Forsyth, John Marsh, and Thomas McKenney were replaced by less qualified men such as Felix St. Vrain. In the 19th century, historian Lyman Draper argued that the Black Hawk War could have been avoided had Forsyth remained as the agent to the Sauks.[52]

In 1830, violence threatened to undo American attempts at preventing intertribal warfare. In May, Dakotas (Santee Sioux) and Menominees killed fifteen Meskwakis attending a treaty conference at Prairie du Chien. In retaliation, a party of Meskwakis and Sauks killed twenty-six Menominees, including women and children, at Prairie du Chien in July 1831.[53] American officials discouraged the Menominees from seeking revenge, but the western bands of the tribe formed a coalition with the Dakotas to strike at the Sauks and Meskwakis.[54]

Hoping to prevent the outbreak of a wider war, American officials ordered the U.S. Army to arrest the Meskwakis who massacred the Menominees.[55] General Gaines was ill, and so his subordinate, Brigadier General Henry Atkinson, received the assignment.[56] Atkinson was a middle-aged officer who had ably handled administrative and diplomatic tasks, most notably during the 1827 Winnebago War, but he had never seen combat.[57] On April 8, he set out from Jefferson Barracks in Missouri, moving up the Mississippi River by steamboat with about 220 soldiers. By chance, Black Hawk and his British Band had just crossed into Illinois. Although Atkinson did not realize it, his boats passed Black Hawk's band.[58]

When Atkinson arrived at Fort Armstrong on Rock Island on April 12, he learned that the British Band was in Illinois, and that most of the Meskwakis he wanted to arrest were now with the band.[59] Like other American officials, Atkinson was convinced that the British Band intended to start a war. Because he had few troops at his disposal, Atkinson hoped to get support from the Illinois state militia. He wrote to Governor Reynolds on April 13, describing—and perhaps purposely exaggerating—the threat that the British Band posed.[60] Reynolds, who was eager for a war to drive the Indians out of the state, responded as Atkinson had hoped: he called for militia volunteers to assemble at Beardstown by April 22 to begin a thirty-day enlistment. The 2,100 men who volunteered were organized into a brigade of five regiments under Brigadier General Samuel Whiteside.[61] Among the militiamen was 23-year-old Abraham Lincoln, who was elected captain of his company.[62]

Initial diplomacy

1.jpg.webp)

After Atkinson's arrival at Rock Island on April 12, 1832, he, Keokuk, and Meskwaki chief Wapello sent emissaries to the British Band, which was now ascending the Rock River. Black Hawk rejected the messages advising him to turn back.[63] Colonel Zachary Taylor, a regular army officer who served under Atkinson, later stated that Atkinson should have made an attempt to stop the British Band by force. Some historians have agreed, arguing that Atkinson could have prevented the outbreak of war with more decisive action or astute diplomacy. Cecil Eby charged that "Atkinson was a paper general, unwilling to proceed until all risk had been eliminated".[64] Kerry Trask, however, argued that Atkinson was correct in believing that he did not yet have enough troops to stop the British Band.[65] According to Patrick Jung, leaders on both sides had little chance of avoiding bloodshed at this point, because the militiamen and some of Black Hawk's warriors were spoiling for a fight.[66]

Meanwhile, Black Hawk learned that the Ho-Chunk and Potawatomi tribes were less supportive than anticipated. As in other tribes, different bands of these tribes often pursued different policies.[67] The Ho-Chunks who lived along the Rock River in Illinois had family ties to the Sauks; they cautiously supported the British Band while trying not to provoke the Americans.[68] Ho-Chunks in Wisconsin were more divided. Some bands, remembering their loss to the Americans in the 1827 Winnebago War, decided to stay clear of the conflict. Other Ho-Chunks with ties to the Dakotas and Menominees, most notably Waukon Decorah and his brothers, were eager to fight against the British Band.[69]

Most Potawatomis wanted to remain neutral in the conflict, but found it difficult to do so.[70] Many settlers, recalling the Fort Dearborn massacre of 1812, distrusted the Potawatomis and assumed that they would join Black Hawk's uprising.[71] Potawatomi leaders worried that the tribe as a whole would be punished if any Potawatomis supported Black Hawk. At a council outside Chicago on May 1, 1832, Potawatomi leaders including Billy Caldwell "passed a resolution declaring any Potawatomi who supported Black Hawk a traitor to his tribe".[72] In mid May, Potawatomi chiefs Shabonna and Waubonsie told Black Hawk that neither they nor the British would come to his aid.[73]

Without British supplies, adequate provisions, or Native allies, Black Hawk realized that his band was in serious trouble.[74] By some accounts, he was ready to negotiate with Atkinson to end the crisis, but an ill-fated encounter with Illinois militiamen would end all possibility of a peaceful resolution.[75]

Stillman's Run

General Samuel Whiteside's militia brigade had been mustered into federal service at Rock Island under General Atkinson in late April, and divided into four regiments (commanded by Colonels John DeWitt, Jacob Fry, John Thomas, and Samuel M. Thompson), and a scout or spy battalion commanded by James D. Henry,[76] with judge William Thomas as their quartermaster. Atkinson had allowed Reynolds, Whiteside, and the militiamen to leave up the Rock River on April 27, while he brought up the rear with the regular soldiers, directing his least trained and disciplined men—to "move upon the Indians should they be within striking distance without waiting for my arrival".[77][78] Governor Reynolds accompanied the expedition as a major general of militia.

On May 10, the militia marching up the Rock River in pursuit of the British Band reached Prophetstown (about 35 miles from their starting point at the confluence). Rather than wait per Atkinson's plan, they burned White Cloud's empty village, and proceeded about 40 miles upriver to Dixon's Ferry, where they waited for Atkinson and his troops.[79][80] Although Reynolds wanted to allow the 260 eager militiamen not yet federalized to continue further as scouts, the cautious Whiteside insisted on waiting for Atkinson at the settlement.[81] Dixon's Ferry had actually been established in 1826 by Ogee, of half-native ancestry, where the wagon trail connecting Peoria to the lead mines in Galena crossed the Rock River; settlers had established cabins along the Peoria/Galena trace and at the crossing, so that by 1829 its post office served settlers up the river as far as Rockford.[82]

On May 12, learning that Black Hawk's band was only twenty-five miles away, eager militiamen led by Major Isaiah Stillman left Whiteside's encampment, making another camp on a tributary of the Rock River later named Stillman Valley after him. Seeing a small party of natives with a red flag, Major Samuel Hackelton and some men pursued without waiting for orders, and Hackelton killed a native before returning to Whiteside's camp with the news.[80] However, Black Hawk and others were nearby, and near dusk on May 14 attacked Stillman's party in what became known as the Battle of Stillman's Run. Accounts of the battle vary.[83] Black Hawk later stated that he sent three men under a white flag to parley, but the Americans imprisoned them and opened fire on a second group of emissaries who followed. Some militiamen claimed they never saw a white flag; others believed that the flag was a ruse the Indians used to set an ambush.[84] All accounts agree that Black Hawk's warriors attacked the militia camp at dusk, that the much more numerous militia were routed, and the survivors straggled into Whiteside's camp. To Black Hawk's surprise, his forty warriors killed twelve Illinois militiamen, and suffered only three fatalities.[85]

The Battle of Stillman's Run proved a turning point. Before the battle, Black Hawk had not committed to war. Now he determined to avenge what he saw as the treacherous killing of his warriors under a flag of truce.[86] Whiteside too was incensed when he returned to the battle site with a burial party and viewed the mutilated corpses.[87] After Stillman's defeat, American leaders like President Jackson and Secretary of War Lewis Cass refused to consider a diplomatic solution; they wanted a resounding victory over Black Hawk to serve as an example to other Native Americans who might consider similar uprisings.[88]

Initial raids

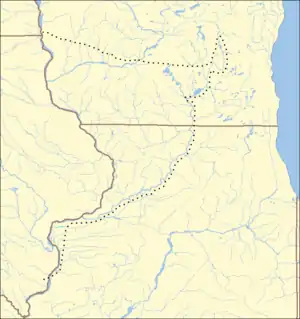

Michigan Territory (Wisconsin)

Illinois

Unorganized

Territory (Iowa)  |

| Map of Black Hawk War sites Symbols are wikilinked to article |

With hostilities now underway, and few allies to depend upon, Black Hawk sought a place of refuge for the women, children, and elderly in his band. Accepting an offer from the Rock River Ho-Chunks, the band traveled further upriver to Lake Koshkonong in the Michigan Territory and camped in an isolated place known as the "Island".[89] With the non-combatants secure, members of the British Band, with a number of Ho-Chunk and Potawatomi allies, began raiding settlers.[90] Not all Native Americans in the region supported this turn of events; most notably, Potawatomi chief Shabonna rode throughout the settlements, warning settlers of the impending attacks.[91]

The initial raiding parties consisted primarily of Ho-Chunk and Potawatomi warriors. The first attack came on May 19, 1832, when Ho-Chunks ambushed six men near Buffalo Grove, Illinois, killing a man named William Durley.[92] Durley's scalped and mutilated body was found by Indian agent Felix St. Vrain. The Indian agent was himself killed and mutilated, along with three other men, several days later at Kellogg's Grove.[93]

The Ho-Chunks and Potawatomis who took part in the war were sometimes motivated by grievances not directly related to Black Hawk's objectives.[94] One such incident was the Indian Creek massacre. In the spring of 1832, Potawatomis living along Indian Creek were upset that a settler named William Davis had dammed the creek, preventing fish from reaching their village. Davis ignored the protests, and assaulted a Potawatomi man who tried to dismantle the dam.[95] The Black Hawk War provided the Indian Creek Potawatomis with an opportunity for revenge. On May 21, about fifty Potawatomis and three Sauks from the British Band attacked Davis's settlement, killing, scalping, and mutilating fifteen men, women, and children.[96] Two teenage girls from the settlement were kidnapped and taken to Black Hawk's camp.[97] A Ho-Chunk chief named White Crow negotiated their release two weeks later.[98] Like other Rock River Ho-Chunks, White Crow was trying to placate the Americans while clandestinely aiding the British Band.[99]

American reorganization

News of Stillman's defeat, the Indian Creek massacre, and other smaller attacks triggered panic among the settlers. Many fled to Chicago, then a small town, which became overcrowded with hungry refugees.[100] Many Potawatomis also fled towards Chicago, not wanting to get caught in the conflict nor be mistaken for hostiles.[101] Throughout the region, settlers hurriedly organized militia units and built small forts.[102]

After Stillman's defeat on May 14, the regulars and militia continued up the Rock River to search for Black Hawk. The militiamen became discouraged at not being able to find the British Band. When they heard about the Indian raids, many deserted so that they could return home to defend their families.[103] As morale plummeted, Governor Reynolds asked his militia officers to vote on whether to continue the campaign. General Whiteside, disgusted with the performance of his men, cast the tie-breaking vote in favor of disbanding.[104] Most of Whiteside's brigade disbanded at Ottawa, Illinois, on May 28. About 300 men, including Abraham Lincoln, agreed to remain in the field for twenty more days until a new militia force could be organized.[105]

As Whiteside's brigade disbanded, Atkinson organized a new force in June 1832 that he dubbed the "Army of the Frontier".[106] The army consisted of 629 regular army infantrymen and 3,196 mounted militia volunteers. The militia was divided into three brigades commanded by Brigadier Generals Alexander Posey, Milton Alexander, and James D. Henry. Since many men were assigned to local patrols and guard duties, Atkinson had only 450 regulars and 2,100 militiamen available for campaigning.[107] Many more militiamen served in units that were not part of the Army of the Frontier's three brigades. Abraham Lincoln, for example, reenlisted as a private in an independent company that was taken into federal service. Henry Dodge, a Michigan territorial militia colonel who would prove to be one of the best commanders in the war,[108] fielded a battalion of mounted volunteers that numbered 250 men at its strongest. The overall number of militiamen who took part in the war is not precisely known; the total from Illinois alone has been estimated at six to seven thousand.[109]

In addition to organizing a new militia army, Atkinson also began to recruit Native American allies, reversing the previous American policy of trying to prevent intertribal warfare.[110] Menominees, Dakotas, and some Ho-Chunks bands were eager to go to war against the British Band. By June 6, agent Joseph M. Street had assembled about 225 Natives at Prairie du Chien.[111] This force included about eighty Dakotas under Wabasha and L'Arc, forty Menominees, and several bands of Ho Chunks.[112] Although the Indian warriors followed their own leaders, Atkinson placed the force under the nominal command of William S. Hamilton, a militia colonel and a son of Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton would prove to be an unfortunate choice to lead the force; historian John Hall characterized him as "pretentious and unqualified".[113] Before long, the Indians became frustrated with marching around under Hamilton and not seeing any action. Some Menominee scouts remained, but most of the Natives eventually left Hamilton and fought the war on their own terms.[114]

June raids

In June 1832, after hearing that Atkinson was forming a new army, Black Hawk began sending out raiding parties. Perhaps hoping to lead the Americans away from his camp at Lake Koshkonong, he targeted areas to the west.[115] The first major attack occurred on June 14 near present-day South Wayne, Wisconsin, when a band of about 30 warriors attacked a group of farmers, killing and scalping four.[116]

Responding to this attack, militia Colonel Henry Dodge gathered a force of twenty-nine mounted volunteers and set out in pursuit of the attackers. On June 16, Dodge and his men cornered about eleven of the raiders at a bend in the Pecatonica River. In a brief battle, the Americans killed and scalped all of the Natives.[117] The Battle of Horseshoe Bend (or Battle of Pecatonica) was the first real American victory in the war, and helped restore public confidence in the volunteer militia force.[118]

On the same day of Dodge's victory, another skirmish took place at Kellogg's Grove in present-day Stephenson County, Illinois. American forces had occupied Kellogg's Grove in an effort to intercept war parties raiding to the west. In the First Battle of Kellogg's Grove, militia commanded by Adam W. Snyder pursued a British Band raiding party of about thirty warriors. Three Illinois militiamen and six Native warriors died in the fighting.[119] Two days later, on June 18, militia under James W. Stephenson encountered what was probably the same war party near Yellow Creek. The Battle of Waddams Grove became a hard-fought, hand-to-hand melee. Three militiamen and five or six Indians were killed in the action.[120]

Back on June 6, when a civilian miner was killed by raiders near the village of Blue Mounds in the Michigan Territory, residents began to fear that the Rock River Ho-Chunks were joining the war.[121] On June 20, a Ho-Chunk raiding party estimated by one eyewitness to be as large as 100 warriors attacked the settler fort at Blue Mounds. Two militiamen were killed in the attack, one of whom was badly mutilated.[122]

On June 24, 1832, Black Hawk and about 200 warriors attacked at the hastily constructed Apple River Fort, near present-day Elizabeth, Illinois. Local settlers, warned of Black Hawk's approach, took refuge in the fort, which was defended by about 20[123] to 35[124] militiamen. The Battle of Apple River Fort lasted about forty-five minutes. The women and girls inside the fort, under the direction of Elizabeth Armstrong, loaded muskets and molded bullets.[123] After losing several men, Black Hawk broke off the siege, looted the nearby homes, and headed back towards his camp.[125]

The next day, June 25, Black Hawk's party encountered a militia battalion commanded by Major John Dement. In the Second Battle of Kellogg's Grove, Black Hawk's warriors drove the militiamen inside their fort and commenced a two-hour siege. After losing nine warriors and killing five militiamen, Black Hawk broke off the siege and returned to his main camp at Lake Koshkonong.[126] This would prove to be Black Hawk's last military success in the war. With his band running low on food, he decided to take them back across the Mississippi.[127]

Final campaign

On June 15, 1832, President Andrew Jackson, displeased with Atkinson's handling of the war, appointed General Winfield Scott to take command.[128] Scott gathered about 950 troops from eastern army posts just as a cholera pandemic had spread to eastern North America.[129] As Scott's troops traveled by steamboat from Buffalo, New York, across the Great Lakes towards Chicago, his men started getting sick from cholera, with many of them dying. At each place the vessels landed, the sick were deposited and soldiers deserted. By the time the last steamboat landed in Chicago, Scott had only about 350 effective soldiers left.[130] On July 29, Scott began a hurried journey west, ahead of his troops, eager to take command of what was certain to be the war's final campaign, but he would be too late to see any combat.[131]

General Atkinson, who learned in early July that Scott would be taking command, hoped to bring the war to a successful conclusion before Scott's arrival.[132] The Americans had difficulty locating the British Band, however, thanks in part to false intelligence given to them by area Native Americans. Potawatomis and Ho-Chunks in Illinois, many of whom had sought to remain neutral in the war, decided to cooperate with the Americans. Tribal leaders knew that some of their warriors had aided the British Band, and so they hoped that a highly visible show of support for the Americans would dissuade U.S. officials from punishing the tribes after the conflict was over. Wearing white headbands to distinguish themselves from hostile Natives, Ho-Chunks and Potawatomis served as guides for Atkinson's army.[133] Ho-Chunks sympathetic to the plight of Black Hawk's people misled Atkinson into thinking that the British Band was still at Lake Koshkonong. While Atkinson's men were trudging through the swamps and running low on provisions, the British Band had in fact relocated miles to the north.[134] Potawatomis under Billy Caldwell also managed to demonstrate support for the Americans while avoiding battle.[135]

In mid-July, Colonel Dodge learned from métis trader Pierre Paquette that the British Band was camped near the Rock River rapids, at present Hustisford, Wisconsin.[136] Dodge and James D. Henry set out in pursuit from Fort Winnebago on July 15.[137] The British Band, reduced to fewer than 600 people due to death and desertion, headed for the Mississippi River as the militia approached.[138] The Americans pursued them, killing and scalping several Native stragglers along the way.[139]

Wisconsin Heights

On July 21, 1832, the militiamen caught up with the British Band near present-day Sauk City, Wisconsin. To buy time for the noncombatants to cross the Wisconsin River, Black Hawk and Neapope confronted the Americans in a rear guard action that became known as the Battle of Wisconsin Heights. Black Hawk was desperately outnumbered, leading about 50 Sauks and 60 to 70 Kickapoos against 750 militiamen.[140] The battle was a lopsided victory for the militiamen, who lost only one man while killing as many as 68 of Black Hawk's warriors.[141] Despite the high casualties, the battle allowed much of the British Band, including many women and children, to escape across the river.[142] Black Hawk had managed to hold off a much larger force while allowing most of his people to escape, a difficult military operation that impressed some U.S. Army officers when they learned of it.[143]

The Battle of Wisconsin Heights had been a victory for the militia; no regular soldiers of the U.S. Army had been present.[144] Atkinson and the regulars joined up with the volunteers several days after the battle. With a force of about 400 regulars and 900 militiamen, the Americans crossed the Wisconsin River on July 27 and resumed the pursuit of the British Band.[145] The British Band was moving slow, encumbered with wounded warriors and people dying of starvation. The Americans followed the trail of dead bodies, cast off equipment, and the remains of horses the hungry Natives had eaten.[146]

Bad Axe

After the Battle of Wisconsin Heights, a messenger from Black Hawk had shouted to the militiamen that the starving British Band was going back across the Mississippi and would fight no more. No one in the American camp understood the message, however, since their Ho-Chunk guides were not present to interpret.[147] Black Hawk may have believed that the Americans had gotten the message, and that they had not pursued him after the Battle of Wisconsin Heights. He apparently expected that the Americans were going to let his band recross the Mississippi untouched.[148]

The Americans, however, had no intentions of letting the British Band escape. The Warrior, a steamboat outfitted with an artillery piece, patrolled the Mississippi River, while American-allied Dakotas, Menominees, and Ho-Chunks watched the banks.[149] On August 1, the Warrior arrived at the mouth of the Bad Axe River, where the Dakotas told the Americans that they would find Black Hawk's people.[150] Black Hawk raised a white flag in an attempt to surrender, but his intentions may have been garbled in translation.[151] The Americans, in no mood to accept a surrender anyway, thought that the Indians were using the white flag to set an ambush. When they became certain that the Natives on land were the British Band, they opened fire. Twenty-three Natives were killed in the exchange of gunfire, while just one soldier on the Warrior was injured.[152]

_(14590318379).jpg.webp)

After the Warrior left, Black Hawk decided to seek refuge in the north with the Ojibwes. Only about 50 people, including Wabokieshiek, agreed to go with him; the others remained, determined to cross the Mississippi and return to Sauk territory.[153] The next morning, on August 2, Black Hawk was heading north when he learned that the American army had closed in on the members of the British Band who were trying to cross the Mississippi.[154] He tried to rejoin the main body, but after a skirmish with American troops near present-day Victory, Wisconsin, he gave up the attempt.[154] Sauk chief Weesheet later criticized Black Hawk and Wabokieshiek for abandoning the people during the final battle of the war.[155]

The Battle of Bad Axe began at about 9:00 am on August 2 after the Americans caught up with the remnants of the British Band a few miles downstream from the mouth of the Bad Axe River. The British Band was reduced to roughly 500 people by this time, including about 150 warriors.[156] The warriors fought with the Americans while the Native noncombatants frantically tried to cross the river. Many made it to one of the two nearby islands, but were dislodged after the steamboat Warrior returned at noon, carrying regulars and Menominees allied with the Americans.[157]

The battle was another lopsided victory for the Americans, who lost just 14 men, including one Menominee who died by friendly fire and was buried with honors alongside the US soldiers.[158] At least 260 members of the British Band were killed, including about 110 who drowned while trying to cross the river. Although the regular soldiers of the U.S. Army generally tried to avoid needless bloodshed, many of the militiamen intentionally killed Native noncombatants, sometimes in cold blood.[159] The encounter was, in the words of historian Patrick Jung, "less of a battle and more of a massacre".[2]

Menominees from Green Bay, who had mobilized a battalion of nearly 300 men, arrived too late for the battle. They were upset at having missed the chance to fight their old enemies, and so on August 10, General Scott sent 100 of them after a part of the British Band that had escaped.[160] Indian agent Samuel C. Stambaugh, who accompanied them, urged the Menominees not to take any scalps, but Chief Grizzly Bear insisted that such a prohibition could not be enforced.[161] The group tracked down about ten Sauks, only two of whom were warriors. The Menominees killed and scalped the warriors, but spared the women and children.[162]

The Dakotas, who had volunteered 150 warriors to fight against the Sauks and Meskwakis, also arrived too late to participate in the Battle of Bad Axe, but they pursued the members of the British Band who made it across the Mississippi into Iowa. On about August 9, in the final engagement of the war,[163] they attacked the remnants of the British Band along the Cedar River, killing 68 and taking 22 prisoners.[164] Ho-Chunks also hunted survivors of the British Band, taking between fifty and sixty scalps.[165]

Aftermath

The Black Hawk War resulted in the deaths of 77 settlers, militiamen, and regular soldiers.[2] This figure does not include the deaths from cholera suffered by the relief force under General Winfield Scott. Estimates of how many members of the British Band died during the conflict range from about 450 to 600, or about half of the 1,100 people who entered Illinois with Black Hawk in 1832.[166]

A number of American men with political ambitions fought in the Black Hawk War. At least seven future U.S. Senators took part, as did four future Illinois governors; future governors of Michigan, Nebraska, and the Wisconsin Territory; and two future U.S. presidents, Taylor and Lincoln.[167] The Black Hawk War demonstrated to American officials the need for mounted troops to fight a mounted foe. During the war, the U.S. Army did not have cavalry; the only mounted soldiers were part-time volunteers. After the war, Congress created the Mounted Ranger Battalion under the command of Henry Dodge, which was expanded to the 1st Cavalry Regiment in 1833.[168]

Black Hawk's imprisonment and legacy

After the Battle of Bad Axe, Black Hawk, Wabokieshiek, and their followers traveled northeast to seek refuge with the Ojibwes. American officials offered a reward of $100 and forty horses for Black Hawk's capture.[169] While camping near present-day Tomah, Wisconsin, Black Hawk's party was seen by a passing Ho-Chunk man, who alerted his village chief. The village council sent a delegation to Black Hawk's camp and convinced him to surrender to the Americans. On August 27, 1832, Black Hawk and Wabokieshiek surrendered at Prairie du Chien to Indian agent Joseph Street.[170] Colonel Zachary Taylor took custody of the prisoners, and sent them by steamboat to Jefferson Barracks, escorted by Lieutenants Jefferson Davis and Robert Anderson.[171]

By war's end, Black Hawk and nineteen other leaders of the British Band were incarcerated at Jefferson Barracks. Most of the prisoners were released in the succeeding months, but in April 1833, Black Hawk, Wabokieshiek, Neapope, and three others were transferred to Fort Monroe in Virginia, which was better equipped to hold prisoners.[172] The American public was eager to catch a glimpse of the captured Indians. Large crowds gathered in Louisville and Cincinnati to watch them pass.[173] On April 26, the prisoners met briefly with President Jackson in Washington, D.C., before being taken to Fort Monroe.[174] Even in prison they were treated as celebrities: they posed for portraits by artists such as Charles Bird King and John Wesley Jarvis, and a dinner was held in their honor before they left.[175]

American officials decided to release the prisoners after a few weeks. First, however, the Natives were required to visit several large U.S. cities on the east coast. This was a tactic often used when Native American leaders came to the East, because it was thought that a demonstration of the size and power of the United States would discourage future resistance to U.S. expansion.[176] Beginning on June 4, 1833, Black Hawk and his companions were taken on a tour of Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York City. They attended dinners and plays, and were shown a battleship, various public buildings, and a military parade. Huge crowds gathered to see them. Black Hawk's handsome son Nasheweskaska (Whirling Thunder) was a particular favorite.[177] Reaction in the west, however, was less welcoming. When the prisoners traveled through Detroit on their way home, one crowd burned and hanged effigies of the Indians.[178]

According to historian Kerry Trask, Black Hawk and his fellow prisoners were treated like celebrities because the Indians served as a living embodiment of the noble savage myth that had become popular in the eastern United States. Then and later, argues Trask, Americans absolved themselves of complicity in the dispossession of Native Americans by expressing admiration or sympathy for defeated Indians like Black Hawk.[179] The mythologizing of Black Hawk continued, argues Trask, with the many plaques and memorials that were later erected in his honor. "Indeed," writes Trask, "most of the reconstructed memory of the Black Hawk War has been designed to make white people feel good about themselves."[180] Black Hawk also became an admired symbol of resistance among Native Americans, even among descendants of those who had opposed him.

Treaties and removals

The Black Hawk War marked the end of Native armed resistance to U.S. expansion in the Old Northwest.[181] The war provided an opportunity for American officials such as Andrew Jackson, Lewis Cass, and John Reynolds to compel Native American tribes to sell their lands east of the Mississippi River and move to the West, a policy known as Indian removal. Officials conducted a number of treaties after the war to purchase the remaining Native American land claims in the Old Northwest. The Dakotas and Menominees, who won approval from American officials for their role in the war, largely avoided postwar removal pressure until later decades.[182]

After the war, American officials learned that some Ho-Chunks had aided Black Hawk more than had been previously known.[183] Eight Ho-Chunks were briefly imprisoned at Fort Winnebago for their role in the war, but charges against them were eventually dropped due to a lack of witnesses.[184] In September 1832, General Scott and Governor Reynolds conducted a treaty with the Ho-Chunks at Rock Island. The Ho-Chunks ceded all their land south of the Wisconsin River in exchange for a forty-mile strip of land in Iowa and annual payments of $10,000 for twenty-seven years.[185] The land in Iowa was known as the "Neutral Ground" because it had been designated in 1830 as a buffer zone between the Dakotas and their enemies to the south, the Sauks and Meskwakis.[186] Scott hoped that the settlement of the Ho-Chunks in the Neutral Ground would help keep the peace.[187] Ho-Chunks remaining in Wisconsin were pressured to sign a removal treaty in 1837, even though leaders such as Waukon Decorah had been U.S. allies during the Black Hawk War. General Atkinson was assigned to use the army to forcibly relocate those Ho-Chunks who refused to move to Iowa.[188]

Following the September 1832 treaty with the Ho-Chunks, Scott and Reynolds conducted another with the Sauks and Meskwakis, with Keokuk and Wapello serving as the primary representatives of their tribes. Scott told the assembled chiefs that "if a particular part of a nation goes out of their country, and makes war, the whole nation is responsible".[187] The tribes sold about 6 million acres (24,000 km2) of land in eastern Iowa to the United States for payments of $20,000 per year for thirty years, among other provisions.[189] Keokuk was granted a reservation within the cession and recognized by the Americans as the primary chief of the Sauks and Meskwakis.[190] The tribes sold the reservation to the United States in 1836, and additional land in Iowa the following year.[191] Their last lands in Iowa were sold in 1842, and most of the Natives moved to a reservation in Kansas.[192]

Thanks to the decision of Potawatomi leaders to aid the U.S. during the war, American officials did not seize tribal land as war reparations. Instead, only three individuals accused of leading the Indian Creek massacre were tried in court; they were acquitted.[193] Nevertheless, the drive to purchase Potawatomi land west of the Mississippi began in October 1832, when commissioners in Indiana bought a large amount of Potawatomi land, even though not all Potawatomi bands were represented at the treaty.[194] The tribe was compelled to sell their remaining land west of the Mississippi in a treaty held in Chicago in September 1833.[195]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Hall, 2: Jung, 174

- 1 2 3 4 Jung, 172.

- ↑ Eby, 17.

- ↑ "Understanding the war between the States – Chapter 24" (PDF).

- ↑ Hall, 21–26; Jung, 13–14; Trask, 29.

- ↑ Jung, 14; Trask, 64.

- ↑ Owens, 87–90.

- ↑ Jung, 21–22.

- ↑ Jung, 32.

- ↑ Trask, 72.

- ↑ Trask, 28–29.

- ↑ Trask, 70; Jung, 52–53.

- ↑ Jung, 52.

- ↑ Jung, 55.

- ↑ Jung, 54–55; Nichols, 78.

- 1 2 Jung, 56.

- ↑ Jung, 53.

- ↑ Jung, 53; Trask, 73.

- ↑ Hall, 90; Trask, 71.

- ↑ Trask, 79.

- ↑ Jung, 59.

- ↑ Jung, 47, 58.

- ↑ Hall, 90, 127; Jung, 56.

- ↑ Jung, 60.

- ↑ Edmunds, 235–36.

- ↑ Eby, 83–86.

- ↑ Eby, 88; Jung, 62.

- ↑ Jung, 62.

- ↑ "View of Vandruff Island from Black Hawk Tower » RIPS".

- ↑ Eby, 88–89; Jung, 63; Trask, 102.

- ↑ Jung, 64; Trask, 105.

- ↑ Hall, 116.

- 1 2 Jung, 66.

- ↑ Jung, 69; Hall, 116.

- ↑ Jung, 74.

- ↑ Trask, 63, 69.

- ↑ Dowd, 193; Hall, 110.

- ↑ Hall, 110.

- ↑ Jung, 74; Hall, 116; Trask, 145, gives a more general date of "probably April 6".

- ↑ Jung, 74–75; Trask, 145.

- ↑ Trask, 149–50; Hall, 129–30.

- ↑ Trask, 150.

- ↑ Jung, 73; Trask, 146–47.

- ↑ Hall, 110; Jung, 73.

- ↑ Eby, 35; Jung, 74–75.

- ↑ Jung 50, 70; Hall, 99–100.

- ↑ Hall, 9.

- ↑ Hall, 100.

- ↑ Hall, 55, 95; Buckley, 165.

- ↑ Buckley, 172–75; Hall, 77–78, 100–02.

- ↑ Hall, 9, 24, 55, 237.

- ↑ Hall, 103–04. Eby, 79, echoed the argument.

- ↑ Jung, 49; Hall, 111.

- ↑ Hall, 113–15.

- ↑ Hall, 115; Jung, 49–50.

- ↑ Hall, 115; Jung, 70.

- ↑ Hall, 115; Jung, 71–72; Trask, 143.

- ↑ Trask, 146.

- ↑ Hall, 117; Jung, 75.

- ↑ Jung, 76; Trask, 158–59.

- ↑ Jung, 79–80; Trask, 174.

- ↑ Jung, 79.

- ↑ Jung, 76–77; Nichols, 117–18.

- ↑ Eby, 93.

- ↑ Trask, 152–55.

- ↑ Jung, 86.

- ↑ Hall, 10–11.

- ↑ Hall, 131.

- ↑ Hall, 122–23; Jung, 78–79.

- ↑ Hall, 125.

- ↑ Hall, 122.

- ↑ Hall, 132.

- ↑ Jung, 86–87; Edmunds, 236.

- ↑ Jung, 83–84; Nichols, 120; Trask, 180–81.

- ↑ Hall, 133.

- ↑ Harrington, George B. Past and Present of Bureau County, Illinois. Chicago, IL, USA: Pioneer Publishing (1906). p. 39

- ↑ Jung, p. 84.

- ↑ Thomas Ford, A History of Illinois: from its commencement as a state in 1818 to 1847, annotated and introduced by Rodney O. Davis. University of Illinois Press (1995). pp. 76–77

- ↑ Prophetstown State Park, Illinois Department of Natural Resources

- 1 2 Ford, p. 78

- ↑ Jung, 85–86.

- ↑ William V. Pooley, "Settlement of Illinois, 1830–1850" (1905). Thesis submitted to the University of Wisconsin. Ann Arbor, Michigan, University Microfilms (1968). p. 147

- ↑ Jung, p. 88; Trask, p. 183.

- ↑ Jung, pp. 88–89; Trask, p. 186.

- ↑ Jung, p. 89; Hall, pp. 133–134.

- ↑ Jung, p. 89.

- ↑ "Battle of Stillman's Run" in William B. Kessell, Encyclopedia of Native American Wars and Warfare (2005), available online

- ↑ Jung, pp. 118–120.

- ↑ Jung, 93–94.

- ↑ Jung, 94, 108.

- ↑ Edmunds, 237; Trask, 200; Jung, 95.

- ↑ Jung, 95; Trask, 198.

- ↑ Jung, 97; Trask, 198–99.

- ↑ Jung, 95.

- ↑ Hall, 135–36.

- ↑ Jung, 95; Trask, 202.

- ↑ Jung, 96; Trask, 215.

- ↑ Trask, 212–17.

- ↑ Hall, 152–54; 164–65.

- ↑ Trask, 200–06; Jung, 97.

- ↑ Edmunds, 238; Jung, 103.

- ↑ Jung, 96.

- ↑ Trask, 194–96.

- ↑ Jung, 100; Trask, 196.

- ↑ Jung, 101; Trask, 196–97.

- ↑ Jung, 115.

- ↑ Jung, 114–15.

- ↑ Jung, 103.

- ↑ Jung, 116.

- ↑ Hall, 143–45.

- ↑ Hall, 148.

- ↑ Hall, 148; Jung 104.

- ↑ Hall, 145.

- ↑ Hall, 162–63; Jung, 105.

- ↑ Jung, 108.

- ↑ Jung, 109.

- ↑ Jung, 109–10; Trask, 233–34.

- ↑ Jung, 110; Trask, 234–37.

- ↑ Jung, 111–12.

- ↑ Jung, 112; Trask, 220–21.

- ↑ Trask, 220.

- ↑ Jung, 112; Trask, 220.

- 1 2 Trask, 222.

- ↑ Jung, 113.

- ↑ Jung, 114.

- ↑ Jung, 121–23.

- ↑ Jung, 124.

- ↑ Jung, 118; Trask, 272.

- ↑ Jung, 139.

- ↑ Jung, 140–41; Trask, 271–75.

- ↑ Jung, 141; Trask, 276.

- ↑ Jung, 130.

- ↑ Edmunds, 239; Hall, 244–49.

- ↑ Jung, 131–34.

- ↑ Hall, 165–67.

- ↑ Jung, 142.

- ↑ Jung, 144.

- ↑ Jung, 146–48.

- ↑ Jung, 149–50.

- ↑ Jung, 153–56.

- ↑ Jung, 156; Trask, 260–61.

- ↑ Lewis, James. "The Black Hawk War of 1832". Abraham Lincoln Digitization Project. Northern Illinois University. p. 2c. Archived from the original on August 15, 2009. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- ↑ Jung, 157.

- ↑ Jung, 156.

- ↑ Jung, 161; Trask, 268.

- ↑ Jung, 162; Trask, 270–71.

- ↑ Nichols, 131; Trask, 266.

- ↑ Jung, 168–69.

- ↑ Hall, 192–94.

- ↑ Jung, 164–65; Hall, 194.

- ↑ Jung, 165; Nichols, 133.

- ↑ Jung, 166; Trask, 279.

- ↑ Jung, 166; Nichols, 133. Jung says "about 60 people" left with Black Hawk; Nichols, 135, estimated "perhaps forty".

- 1 2 Jung, 169.

- ↑ Jung, 180–81; Trask, 282.

- ↑ Jung, 170.

- ↑ Trask, 286–87; Jung, 170–71.

- ↑ Jung, 171–72; Hall, 196.

- ↑ Trask, 285–86, 293.

- ↑ Hall, 197.

- ↑ Hall, 198.

- ↑ Hall, 199.

- ↑ Hall, 202.

- ↑ Jung, 175; Hall, 201.

- ↑ Jung, 177; Hall, 210–11.

- ↑ Jung, 172, 179.

- ↑ Lewis, James. "The Black Hawk War of 1832". Abraham Lincoln Historical Digitization Project. Northern Illinois University. p. 2d. Archived from the original on June 19, 2009. Retrieved August 11, 2009.

- ↑ Jung 205–06.

- ↑ Jung, 181.

- ↑ Jung, 182; Trask, 294–95.

- ↑ Jung, 183.

- ↑ Jung, 190–91.

- ↑ Trask, 298; Jung, 192.

- ↑ Jung, 192; Trask, 298.

- ↑ Nichols, 147; Trask, 298.

- ↑ Jung, 191; Nichols, 148; Trask, 300.

- ↑ Jung, 195–97; Nichols, 148–49; Trask, 300–01.

- ↑ Trask, 301–02; Jung, 197.

- ↑ Trask, 298–303.

- ↑ Trask, 308.

- ↑ Buckley, 210; Hall, 255; Jung, 208.

- ↑ Hall, 207.

- ↑ Hall, 209–10.

- ↑ Jung, 207.

- ↑ Hall, 212–13; Jung, 285–86.

- ↑ Jung, 49; Buckley, 203.

- 1 2 Jung, 186.

- ↑ Hall, 259–61.

- ↑ Trask, 304; Jung, 187.

- ↑ Jung, 187.

- ↑ Jung, 198.

- ↑ Jung, 201–02.

- ↑ Edmunds, 238; Hall, 208, 215.

- ↑ Hall, 215–16.

- ↑ Edmunds, 247–48; Hall, 231.

References

Secondary sources

- Buckley, Jay H. William Clark: Indian Diplomat. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-8061-3911-1

- Drake, Benjamin. The life and adventures of Black Hawk: with sketches of Keokuk, the Sac and Fox Indians, and the late Black Hawk war. 1849. The life and adventures of Black Hawk: with sketches of Keokuk, the Sac and Fox Indians, and the late Black Hawk war.

- Eby, Cecil. "That Disgraceful Affair", The Black Hawk War. New York: Norton, 1973. ISBN 0-393-05484-5

- Edmunds, R. David. The Potawatomis: Keepers of the Fire. University of Oklahoma Press, 1978. ISBN 0-8061-1478-9

- Hall, John W. Uncommon Defense: Indian Allies in the Black Hawk War. Harvard University Press, 2009. ISBN 0-674-03518-6

- Jung, Patrick J. The Black Hawk War of 1832. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007. ISBN 0-8061-3811-4

- Lewis, James E. "The Black Hawk War: Background". Northern Illinois University Digital Library. Accessed 8 December 2023.

- Nichols, Roger L. Black Hawk and the Warrior's Path. Arlington Heights, Illinois: Harlan Davidson, 1992. ISBN 0-88295-884-4

- Nichols, Roger L. Warrior Nations: The United States and Indian Peoples. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013

- Owens, Robert M. Mr. Jefferson's Hammer: William Henry Harrison and the Origins of American Indian Policy. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-8061-3842-8

- Trask, Kerry A. Black Hawk: The Battle for the Heart of America. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 2006. ISBN 0-8050-7758-8

Primary sources

- Black Hawk. Life of Black Hawk. Originally published 1833. Reprinted often in various editions. Revised in 1882 with inauthentic embellishments; most modern editions restore the original wording.

- Whitney, Ellen M., ed. The Black Hawk War, 1831–1832: Volume I, Illinois Volunteers. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Historical Library, 1970. ISBN 0-912154-22-5. Published as Volume XXXV of Collections of the Illinois State Historical Library. Available online from the Internet Archive.

- ———, ed. The Black Hawk War, 1831–1832: Volume II, Letters & Papers, Part I, April 30, 1831 – June 23, 1832. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Historical Library, 1973. ISBN 0-912154-22-5. Published as Volume XXXVI of Collections of the Illinois State Historical Library. Available online from the Internet Archive.

- ———, ed. The Black Hawk War, 1831–1832: Volume II, Letters & Papers, Part II, June 24, 1832 – October 14, 1834. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Historical Library, 1975. ISBN 0-912154-24-1. Published as Volume XXXVII of Collections of the Illinois State Historical Library.

- ———, ed. The Black Hawk War, 1831–1832: Volume II, Letters and Papers, Part III, Appendices and Index. Springfield, Illinois: Illinois State Historical Library, 1978. Published as Volume XXXVIII of Collections of the Illinois State Historical Library.

External links

| Library resources about Black Hawk War |

- The Autobiography of Ma-Ka-Tai-Me-She-Kia-Kiak, or Black Hawk at Standard Ebooks

- The Black Hawk War of 1832, Abraham Lincoln Historical Digitization Project, Northern Illinois University

- Turning Points in Wisconsin History: The Black Hawk War (documents from the Wisconsin Historical Society)

- Webcast Lecture at the Pritzker Military Museum & Library by John W. Hall on March 27, 2010

- Black Hawk's autobiography through the interpretation of Antoine LeClaire ; J.B. Patterson, amanuensis and editor of the first edition; an introduction and notes, critical and historical, by James D. Rishell. 1912.

- The Black Hawk watch tower in the county of Rock Island, State of Illinois by John H. Hauberg for Rock Island Chamber of Commerce. 1925.