Black-figure pottery painting, also known as the black-figure style or black-figure ceramic (Ancient Greek: μελανόμορφα, romanized: melanómorpha), is one of the styles of painting on antique Greek vases. It was especially common between the 7th and 5th centuries BCE, although there are specimens dating as late as the 2nd century BCE. Stylistically it can be distinguished from the preceding orientalizing period and the subsequent red-figure pottery style.

Figures and ornaments were painted on the body of the vessel using shapes and colors reminiscent of silhouettes. Delicate contours were incised into the paint before firing, and details could be reinforced and highlighted with opaque colors, usually white and red. The principal centers for this style were initially the commercial hub Corinth, and later Athens. Other important production sites are known to have been in Laconia, Boeotia, eastern Greece, and Italy. Particularly in Italy individual styles developed which were at least in part intended for the Etruscan market. Greek black-figure vases were very popular with the Etruscans, as is evident from frequent imports. Greek artists created customized goods for the Etruscan market which differed in form and decor from their normal products. The Etruscans also developed their own black-figure ceramic industry oriented on Greek models.

Black-figure painting on vases was the first art style to give rise to a significant number of identifiable artists. Some are known by their true names, others only by the pragmatic names they were given in the scientific literature. Attica especially was the home of well-known artists. Some potters introduced a variety of innovations which frequently influenced the work of the painters; sometimes it was the painters who inspired the potters’ originality. Red- as well as black-figure vases are some of the most important sources of mythology and iconography, and sometimes also for researching day-to-day ancient Greek life. Since the 19th century CE at the latest, these vases have been the subject of intensive investigation.

Production techniques

The foundation for pottery painting is the vase onto which an image is painted. Popular shapes alternated with passing fashions. Whereas many recurred after intervals, others were replaced over time. They all had a common method of manufacture: after the vase was made, it was first dried before being painted. The workshops were under the control of the potters, who as owners of businesses had an elevated social position.

The extent to which potters and painters were identical is uncertain. It is likely that many master potters themselves made their main contribution in the production process as vase painters, while employing additional painters. It is, however, not easy to reconstruct links between potters and painters. In many cases, such as Tleson and the Tleson Painter, Amasis and the Amasis Painter or even Nikosthenes and Painter N, it is impossible to make unambiguous attributions, although in much of the scientific literature these painters and potters are assumed to be the same person. But such attributions can only be made with confidence if the signatures of potter and painter are at hand.

The painters, who were either slaves or craftsmen paid as pottery painters, worked on unfired, leather-dry vases. In the case of black-figure production the subject was painted on the vase with a clay slurry (a slip, in older literature also designated as varnish) which turned black and glossy after firing. This was not "paint" in the usual sense, since this surface slip was made from the same clay material as the vase itself, only differing in the size of the component particles, achieved during refining the clay before potting began. The area for the figures was first painted with a brush-like implement. The internal outlines and structural details were incised into the slip so that the underlying clay could be seen through the scratches. Two other earth-based pigments giving red and white were used to add details such as ornaments, clothing or parts of clothing, hair, animal manes, parts of weapons and other equipment. White was also frequently used to represent women's skin.

The success of all this effort could only be judged after a complicated, three-phase firing process which generated the red color of the body clay and the black of the applied slip. The vessel was fired in a kiln at a temperature of about 800 °C, with the resultant oxidization turning the vase a reddish-orange color. The temperature was then raised to about 950 °C with the kiln's vents closed and green wood added to remove the oxygen. The vessel then turned an overall black. The final stage required the vents to be re-opened to allow oxygen into the kiln, which was allowed to cool down. The vessel then returned to its reddish-orange colour due to renewed oxidization, while the now-sintered painted layer remained the glossy black color which had been created in the second stage.

Although scoring is one of the main stylistic indicators, some pieces do without. For these, the form is technically similar to the orientalizing style, but the image repertoire no longer reflects orientalizing practice.[1]

Developments

The evolution of black-figure pottery painting is traditionally described in terms of various regional styles and schools. Using Corinth as the hub, there were basic differences in the productions of the individual regions, even if they did influence each other. Especially in Attica, although not exclusively there, the best and most influential artists of their time characterized classical Greek pottery painting. The further development and quality of the vessels as image carrier are the subjects of this section.

Corinth

.jpg.webp)

The black-figure technique was developed around 700 BC in Corinth[2] and used for the first time in the early 7th century BC by Proto-Corinthian pottery painters, who were still painting in the orientalizing style. The new technique was reminiscent of engraved metal pieces, with the more costly metal tableware being replaced by pottery vases with figures painted on them. A characteristic black-figure style developed before the end of the century. Most orientalizing elements had been given up and there were no ornaments except for dabbed rosettes (the rosettes being formed by an arrangement of small individual dots)

The clay used in Corinth was soft, with a yellow, occasionally green tint. Faulty firing was a matter of course, occurring whenever the complicated firing procedure did not function as desired. The result was often unwanted coloring of the entire vase, or parts of it. After firing, the glossy slip applied to the vase turned dull black. The supplemental red and white colors first appeared in Corinth and then became very common. The painted vessels are usually of small format, seldom higher than 30 cm. Oil flasks (alabastra, aryballos), pyxides, kraters, oenochoes and cups were the most common vessels painted. Sculptured vases were also widespread. In contrast to Attic vases, inscriptions are rare, and painters’ signatures even more so. Most of the surviving vessels produced in Corinth have been found in Etruria, lower Italy and Sicily. In the 7th and first half of the 6th centuries BC, Corinthian vase painting dominated the Mediterranean market for ceramics. It is difficult to construct a stylistic sequence for Corinthian vase painting. In contrast to Attic painting, for example, the proportions of the pottery foundation did not evolve much. It is also often difficult to date Corinthian vases; one frequently has to rely on secondary dates, such as the founding of Greek colonies in Italy. Based on such information an approximate chronology can be drawn up using stylistic comparisons, but it seldom has anywhere near the precision of the dating of Attic vases.

Mythological scenes are frequently depicted, especially Heracles and figures relating to the Trojan War. But the imagery on Corinthian vases does not have as wide a thematic range as do later works by Attic painters. Gods are seldom depicted, Dionysus never. But the Theban Cycle was more popular in Corinth than later in Athens. Primarily fights, horsemen and banquets were the most common scenes of daily life, the latter appearing for the first time during the early Corinthian period. Sport scenes are rare. Scenes with fat-bellied dancers are unique and their meaning is disputed up to the present time. These are drinkers whose bellies and buttocks are padded with pillows and they may represent an early form of Greek comedy.[3]

Transitional style

The transitional style (640-625 BC) linked the orientalizing (Proto-Corinthian) with the black-figure style. The old animal frieze style of the Proto-Corinthian period had run dry, as did the interest of vase painters in mythological scenes. During this period animal and hybrid creatures were dominant. The index form of the time was the spherical aryballos, which was produced in large numbers and decorated with animal friezes or scenes of daily life. The image quality is inferior compared with the orientalizing period. The most distinguished artists of the time were the Shambling Bull Painter, whose most famous work is an aryballos with a hunting scene, the Painter of Palermo 489, and his disciple, the Columbus Painter. The latter's personal style can be most easily recognized in his images of powerful lions. Beside the aryballos, the kotyle and the alabastron are the most important vase shapes. The edges of kotyles were ornamented, and the other decorations consisted of animals and rays. The two vertical vase surfaces frequently have mythological scenes. The alabastrons were usually painted with single figures.

Early- and Middle Corinthian

The Duel Painter was the most important early Corinthian painter (625-600 BC)[4] who depicted fighting scenes on aryballos. Starting in the Middle Corinthian period (600-575 BC), opaque colors were used more and more frequently to emphasize details. Figures were additionally painted using a series of white dots. The aryballos became larger and were given a flat base.

The Pholoe Painter is well known, his most famous work being a skyphos with a picture of Heracles. The Dodwell Painter continued to paint animal friezes, although other painters had already given up this tradition.[5] His creative period extended into the Late-Corinthian period (575–550 BC) and his influence cannot be overestimated on vase painting of that time. Likewise of exceptional reputation were the master of the Gorgoneion Group and the Cavalcade Painter, given this designation because of his preference for depicting horsemen on cup interiors; he was active around 580 BC.[6] Two of his masterpieces[7] are a cup[8] showing the suicide of Ajax, and a column krater showing a bridal couple in a chariot. All figures shown on the bowl are labeled.

The first artist known by name is the polychrome vase painter Timonidas, who signed[9] a flask[10] and a pinax.[11] A second artist's name of Milonidas also appears on a pinax.

The Corinthian olpe wine jug was replaced by an Attic version of the oinochoe with a cloverleaf lip. In Middle Corinthian time, depictions of people again became more common. The Eurytios Krater dated around 600 BC is considered to be of particularly high quality; it shows a symposium in the main frieze with Heracles, Eurytios, and other mythical figures.

Late Corinthian

In Late Corinthian times (sometimes designated Late Corinthian I, 575–550 BC) Corinthian vases had a red coating to enhance the contrast between the large white areas and the rather pale color of the clay vessel. This put the Corinthian craftsmen in competition with Attic pottery painters, who had in the meantime taken over a leading role in the pottery trade. Attic vase forms were also increasingly copied. Oinochoes, whose form had remained basically unchanged up until that time, began to resemble Attic forms; lekythos also started to be increasingly produced. The column krater, a Corinthian invention which was for that reason called a korinthios in the rest of Greece, was modified. Shortening the volutes above the handles gave rise to the Chalcidic krater. The main image field it was decorated with various representations of daily life or mythological scenes, the secondary field contained an animal frieze. The back often showed two large animals.

Cups had become deeper already in Mid-Corinthian times and this trend continued. They became just as popular as kotyles. Many of them have mythological scenes on the outside and a gorgon grimace on the inside. This type of painting was also adopted by Attic painters. On their part, Corinthian painters took over framed image fields from Athens. Animal friezes became less important. During this time the third Corinthian painter with a known name, Chares, was active.[12] The Tydeus Painter should also be mentioned, who around 560 BC liked to paint neck amphoras with a red background.[13] Incised rosettes continued to be put on vases; they are lacking on only a few kraters and cups. The most outstanding piece of art in this period is the Amphiaraos Krater, a column krater created around 560 BC as the major work of the Amphiaraos Painter. It shows several events from the life of the hero Amphiaraos.

Around 550 BC the production of figured vases came to an end. The following Late Corinthian Style II is characterized by vases only with ornaments, usually painted with a silhouette technique. It was succeeded by the red-figure style, which however did not attain a particularly high quality in Corinth.

Attica

With over 20,000 extant pieces, Attic black-figure vases comprise the largest and at the same time most significant vase collection, second only to Attic red-figure vases.[14] Attic potters benefitted from the excellent, iron-rich clay found in Attica. High quality Attic black-figure vases have a uniform, glossy, pitch-black coating and the color-intensive terra cotta clay foundation has been meticulously smoothened. Women's skin is always indicated with a white opaque color, which is also frequently used for details such as individual horses, clothing or ornaments. The most outstanding Attic artists elevated vase painting to a graphic art, but a large number of average quality and mass-market products were also produced. The outstanding significance of Attic pottery comes from their almost endless repertoire of scenes covering a wide range of themes. These provide rich testimonials especially in regard to mythology, but also to daily life. On the other hand, there are virtually no images referring to contemporary events. Such references are only occasionally evident in the form of annotations, for example when kalos inscriptions are painted on a vase. Vases were produced for the domestic market on the one hand, and were important for celebrations or in connection with ritual acts. On the other hand, they were also an important export product sold throughout the Mediterranean area. For this reason most of the surviving vases come from Etruscan necropolises.[15]

Pioneers

The black-figure technique was first applied in the middle of the 7th century BC, during the period of Proto-Attic vase painting. Influenced by pottery from Corinth, which offered the highest quality at the time, Attic vase painters switched to the new technology between about 635 BC and the end of the century. At first they closely followed the methods and subjects of the Corinthian models. The Painter of Berlin A 34 at the beginning of this period is the first identified individual painter. The first artist with a unique style was the Nessos Painter. With his Nessos amphora he created the first outstanding piece in the Attic black-figure style.[16] At the same time he was an early master of the Attic animal frieze style. One of his vases was also the first known Attic vase exported to Etruria.[17] He was also responsible for the first representations of harpies and Sirens in Attic art. In contrast to the Corinthian painters he used double and even triple incised lines to better depict animal anatomy. A double-scored shoulder line became a characteristic of Attic vases. The possibilities inherent in large pieces of pottery such as belly amphoras as carriers for images were also recognized at an early date. Other important painters of this pioneer time were the Piraeus Painter, the Bellerophon Painter and the Lion Painter.

Early Attic vases

The black-figure style became generally established in Athens around 600 BC. An early Athenian development was the horse-head amphora, the name coming from the depiction of horse heads in an image window. Image windows were frequently used in the subsequent period and were later adopted even in Corinth. The Cerameicus Painter and the Gorgon Painter are associated with the horse-head amphoras. The Corinthian influence was not only maintained, but even intensified. The animal frieze was recognized as generally obligatory and customarily used. This had economic as well as stylistic reasons, because Athens competed with Corinth for markets. Attic vases were sold in the Black Sea area, Libya, Syria, lower Italy and Spain, as well as within the Greek homeland.

In addition to following Corinthian models, Athens vases also showed local innovations. Thus at the beginning of the 6th century BC a "Deianaira type" of lekythos arose, with an elongated, oval form.[18] The most important painter of this early time was the Gorgon Painter (600–580 BC). He was a very productive artist who seldom made use of mythological themes or human figures, and when he did, always accompanied them with animals or animal friezes. Some of his other vases had only animal representations, as was the case with many Corinthian vases. Besides the Gorgon Painter the painters of the Komast Group (585–570 BC) should be mentioned. This group decorated types of vases which were new to Athens, namely lekanes, kotyles and kothons. The most important innovation was however the introduction of the komast cup, which along with the "prekomast cups" of the Oxford Palmette Class stands at the beginning of the development of Attic cups. Important painters in this group were the elder KX Painter and the somewhat less talented KY Painter, who introduced the column krater to Athens.[19] These vessels were designed for use at banquets and were thus decorated with relevant komos scenes, such as komast performers komos scenes.

Other significant painters of the first generation were the Panther Painter, the Anagyrus Painter, the Painter of the Dresden Lekanis and the Polos Painter. The last significant representative of the first generation of painters was Sophilos (580–570 BC), who is the first Attic vase painter known by name. In all, he signed four surviving vases, three as painter and one as potter, revealing that at this date potters were also painters of vases in the black-figure style. A fundamental separation of both crafts seems to have occurred only in the course of the development of the red-figure style, although prior specialization cannot be ruled out. Sophilos makes liberal use of annotations. He apparently specialized in large vases, since especially dinos and amphoras are known to be his work. Much more frequently than his predecessors, Sophilos shows mythological scenes like the funeral games for Patroclus. The decline of the animal frieze begins with him, and plant and other ornaments are also of lower quality since they are regarded as less important and thus receive scant attention from the painter. But in other respects Sophilos shows that he was an ambitious artist. On two dinos the marriage of Peleus and Thetis is depicted. These vases were produced at about the same time as the François vase, which depicts this subject to perfection. However, Sophilos does without any trimmings in the form of animal friezes on one of his two dinos,[20] and he does not combine different myths in scenes distributed over various vase surfaces. It is the first large Greek vase showing a single myth in several interrelated segments. A special feature of the dinos is the painter's application of the opaque white paint designating women directly on the clay foundation, and not as usual on the black gloss. The figure's interior details and contours are painted in a dull red. This particular technique is rare, only found in vases painted in Sophilos' workshop and on wooden panels painted in the Corinthian style in the 6th century BC. Sophilos also painted one of the rare chalices (a variety of goblet) and created the first surviving series of votive tablets. He himself or one of his successors also decorated the first marriage vase (known as a lebes gamikos) to be found.[21]

Pre-Classical Archaic period

Starting around the second third of the 6th century BC, Attic artists became interested in mythological scenes and other representations of figures. Animal friezes became less important. Only a few painters took care with them, and they were generally moved from the center of attention to less important areas of vases. This new style is especially represented by the François vase, signed by both the potter Ergotimos and the painter Kleitias (570–560 BC). This krater is considered to be the most famous Greek painted vase.[22] It is the first known volute krater made of clay. Mythological events are depicted in several friezes, with animal friezes being shown in secondary locations. Several iconographic and technical details appear on this vase for the first time. Many are unique, such as the representation of a lowered mast of a sailing ship; others became part of the standard repertoire, such as people sitting with one leg behind the other, instead of with the traditional parallel positioning of the legs.[23] Four other, smaller vases were signed by Ergotimos and Kleitias, and additional vases and fragments are attributed to them. They provide evidence for other innovations by Kleitias, like the first depiction of the birth of Athena or of the Dance on Crete.

Nearchos (565–555 BC) signed as potter and painter. He favored large figures and was the first to create images showing the harnessing of a chariot. Another innovation was to place a tongue design on a white background under the vase lip.[24] Other talented painters were the Painter of Akropolis 606 and the Ptoon Painter, whose most well-known piece is the Hearst Hydria. The Burgon Group is also significant, being the source of the first totally preserved Panathenaic amphora.

The Siana cup evolved from the komast cup around 575 BC. While the Komast Group produced shapes other than cups, some craftsmen specialized in cup production after the time of the first important exemplifier of Siana cups, the C Painter (575-555 BC). The cups have a higher rim than previously and a trumpet-shaped base on a relatively short hollow stem. For the first time in Attic vase painting the inside of the cup was decorated with framed images (tondo). There were two types of decoration. In the "double-decker" style the cup body and the lip each have separate decorations. In the "overlap" style the image extends over both body and lip. After the second quarter of the 6th century BC there was more interest in decorating especially cups with pictures of athletes. Another important Siana cup painter was the Heidelberg Painter. He, too, painted almost exclusively Siana cups. His favorite subject was the hero Heracles. The Heidelberg Painter is the first Attic painter to show him with the Erymanthian boar, with Nereus, with Busiris and in the garden of the Hesperides. The Cassandra Painter, who decorated mid-sized cups with high bases and lips, marks the end of the development of the Siana cup. He is primarily significant as the first known painter to belong to the so-called Little Masters, a large group of painters who produced the same range of vessels, known as Little-master cups. So-called Merrythought cups were produced contemporaneously with Siana cups. Their handles are in the form of a two-pronged fork and end in what looks like a button. These cups do not have a delineated rim. They also have a deeper bowl with a higher and narrower foot.

The last outstanding painter of the Pre-Classical Archaic Period was Lydos (560-540 BC), who signed two of his surviving pieces with ho Lydos (the Lydian). He or his immediate ancestors probably came from Asia Minor but he was undoubtedly trained in Athens. Over 130 surviving vases are now attributed to him. One of his pictures on a hydria is the first known Attic representation of the fight between Heracles and Geryon. Lydos was the first to show Heracles with the hide of a lion, which afterward became common in Attic art. He also depicted the battle between the gods and the giants on a dinos found on Athens’ acropolis, and Heracles with Cycnus. Lydos decorated other types of vessels besides hydriai and dinos, such as plates, cups (overlap Siena cups), column kraters and psykters, as well as votive tablets. It continues to be difficult to identify Lydos’ products as such since they frequently differ only slightly from those of his immediate milieu. The style is quite homogenous, but the pieces vary considerably in quality. The drawings are not always carefully produced. Lydos was probably a foreman in a very productive workshop in Athens’pottery district. He was presumably the last Attic vase painter to put animal friezes on large vases. Still in the Corinthian tradition, his figure drawings are a link in the chain of vase painters extending from Kleitias via Lydos and the Amasis Painters to Exekias. Along with them he participated in the evolution of this art in Attica and had a lasting influence.[25]

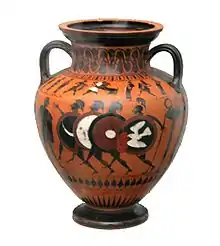

A special form of Attic vases of this period was the Tyrrhenian amphora (550-530 BC). These were egg-shaped neck amphora with decorations atypical of the usual Attic design canon of the period. Almost all of the c. 200 surviving vases were found in Etruria. The body of the amphora is usually subdivided into several parallel friezes. The upper or shoulder frieze usually shows a popular scene from mythology. There are sometimes less common subjects, such as a unique scene of the sacrificing of Polyxena. The first known erotic images on Attic vases are also found at this vase location. The painters frequently put annotations on Tyrrhenian amphora which identify the persons shown. The other two or three friezes were decorated with animals; sometimes one of them was replaced with a plant frieze. The neck is customarily painted with a lotus palmette cross or festoons. The amphoras are quite colorful and recall Corinthian products. In this case a Corinthian form was obviously deliberately copied to produce a particular vase type for the Etruscan market, where the style was popular. It is possible that this form was not manufactured in Athens but somewhere else in Attica, or even outside Attica. Important painters were the Castellani Painter and the Goltyr Painter.

The years of mastery

The period between 560 and the inception of red-figure pottery painting around 530/520 BC is considered to be the absolute pinnacle of black-figure vase painting. In this period the best and most well-known artists exploited all the possibilities offered by this style.[26]

The first important painter of this time was the Amasis Painter (560–525 BC), named after the famous potter Amasis, with whom he primarily worked. Many researchers regard them as the same person. He began his painting career at about the same time as Lydos but was active over a period almost twice as long. Whereas Lydos showed more the abilities of a skilled craftsman, the Amasis Painter was an accomplished artist. His images are clever, charming and sophisticated[27] and his personal artistic development comes close to a reflection of the overall evolution of black-figure Attic vase painting at that time. His early work shows his affinity to the painters of Siana cups. Advances can be most easily recognized in how he draws the folds of clothing. His early female figures wear clothes without folds. Later he paints flat, angular folds, and in the end he is able to convey the impression of supple, flowing garments.[28] Drawings of garments were one of his chief characteristics; he liked to depicted patterned and fringed clothing. The groups of figures which the Amasis Painter shows were carefully drawn and symmetrically composed. Initially they were quite static, later figures convey an impression of motion. Although the Amasis Painter often depicted mythological events—he is known for his pig-faced satyrs, for example—he is better known for his scenes of daily life. He was the first painter to portray them to a significant extent. His work decisively influenced the work of red-figure painters later. He possibly anticipated some of their innovations or was influenced by them toward the end of his painting career: on many of his vases women are only shown in outline, without a black filling, and they are no longer identifiable as women by the application of opaque white as skin color.[29]

Group E (550–525 v. Chr.) was a large, self-contained collection of artisans, and is considered to be the most important anonymous group producing black-figure Attic pottery. It rigorously broke with the stylistic tradition of Lydos both as to image and vessel. Egg-shaped neck amphoras were completely given up, column kraters almost entirely abandoned. Instead, this group introduced Type A belly amphoras, which then became an index form. Neck amphoras were usually produced only in customized versions. The group had no interest in small formats. Many scenes, especially those originating in myths, were reproduced again and again. Thus several amphoras of this group show Heracles with Geryon or the Nemean Lion, and increasingly Theseus and the Minotaur, as well as the birth of Athena. The particular significance of the group is, however, in the influence it exerted on Exekias. Most Attic artists of the period copied the styles of Group E and Exekias. The work of Lydos and the Amasis Painter was, by contrast, not imitated as frequently. Beazley describes the importance of the group for Exekias as follows: "Group E is the fertile ground from which the art of Exekias sprouts, the tradition which he takes up and surpasses on his way from an excellent craftsman to a true artist".[30]

Exekias (545-520 BC) is generally considered to be the absolute master of the black-figure style, which reaches its apex with him.[31] His significance is not only due to his masterful vase painting, but also to his high quality and innovative pottery. He signed 12 of his surviving vessels as potter, two as both painter and potter. Exekias probably had a large role in the development of Little-master cups and the Type A belly amphora mentioned above, and he possibly invented the calyx krater, at least the oldest existing piece is from his workshop. In contrast to many other comparable craftsmen, as a painter he attached great importance to the careful elaboration of ornaments. The details of his images—horses’ manes, weapons, clothing—are also outstandingly well executed. His scenes are usually monumental and the figures emanate a dignity previously unknown in painting. In many cases he broke with Attic conventions. For his most famous vessel, the Dionysus cup, he was the first to use a coral-red interior coating instead of the customary red color. This innovation, as well as his placing of two pairs of eyes on the exterior, connects Exekias with the classic eye cups. Probably even more innovative was his use of the entire inside of the cup for his picture of Dionysus, reclining on a ship from which grapevines sprout. At this time it was in fact customary to decorate the inside surface merely with a gorgon face. The cup[32] is probably one of the experiments undertaken in the pottery district to break new ground before the red-figure style was introduced. He was the first to paint a ship sailing along the rim of a dinos. He only seldom adhered to traditional patterns of depicting customary mythological subjects. His depiction of the suicide of Ajax is also significant. Exekias does not show the act itself, which was in the tradition, but rather Ajax’ preparations.[33] About as famous as the Dionysus cup is an amphora with his visualization of Ajax and Achilles engaged in a board game.[34] Not only is the portrayal detailed, Exekias even conveys the outcome of the game. Almost in the style of a speech balloon he has both players announce the numbers they cast with their dice—Ajax a three and Achilles a four. This is the oldest known depiction of this scene, of which there is no mention in classical literature. No fewer than 180 other surviving vases, dating from the Exekias version up to about 480 BC, show this scene.[35]

John Boardman emphasizes the exceptional status of Exekias which singles him out from traditional vase painters: "The people depicted by earlier artist are elegant dolls at best. Amasis (the Amasis Painter) was able to visualize people as people. But Exekias could envision them as gods and thereby give us a foretaste of classical art".[36]

Acknowledging that vase painters in ancient Greece were regarded as craftsmen rather than artists, Exekias is nevertheless considered by today's art historians to be an accomplished artist whose work can be compared with "major" paintings (murals and panel paintings) of that period.[37] His contemporaries apparently recognized this as well. The Berlin Collection of Classical Antiquities in the Altes Museum contains the remnants of a series of his votive tablets. The complete series probably had 16 individual panels. Placing such an order with a potter and vase painter is likely to be unique in antiquity and is evidence of the high reputation of this artist. The tablets show grieving for a dead Athenian woman as well as her lying in state and being transported to a gravesite. Exekias conveys both the grief and the dignity of the figures. One special feature, for example, is that the leader of the funeral procession turns his face to look at the viewer directly, so to speak. The depiction of the horses is also unique; they have individual temperaments and are not reduced to their function as noble animals, as is otherwise customary on vases.[38]

There was further specialization among producers of vessels and cups during the mature Classical Period. The large-volume komast and Siana cups evolved via Gordion cups[39] into graceful variants called Little-master cups because of their delicate painting. The potters and painters of this form are accordingly called Little Masters. They chiefly painted band cups and lip cups. The lip cups[40] got their name from their relatively pronounced and delineated lip. The outside of the cup retained much of the clay background and typically bore only a few small images, sometimes only inscriptions, or in some cases the entire cup was only minimally decorated. Also in the area of the handles there are seldom more than palmettes or inscriptions near the attachment points. These inscriptions can be the potter's signature, a drinker's toast, or simply a meaningless sequence of letters. But lip cup interiors are often also decorated with images.

Band cups[41] have a softer transition between the body and the rim. The decoration is in the form of a band circling the cup exterior and can frequently be a very elaborate frieze. In the case of this form the rim is coated with a glossy black slip. The interior retains the color of the clay, except for a black dot painted in the center. Variations include Droop cups and Kassel cups. Droop cups[42] have black, concave lips and a high foot. As with classic band cups the rim is left black, but the area below it is decorated with ornaments like leaves, buds, palmettes, dots, nimbuses or animals on the cup exterior. Kassel cups[43] are a small form, squatter than other Little Masters cups, and the entire exterior is decorated. As in the case of Droop cups, primarily ornaments are painted. Famous Little Masters are the potters Phrynos, Sokles, Tleson and Ergoteles, the latter two being sons of the potter Nearchos. Hermogenes invented a Little Master variety of skyphos[44] now known as a Hermogenes skyphos. The Phrynos Painter, Taleides Painter, Xenokles Painter and the Group of Rhodes 12264 should also be mentioned here.

Lip cup by the potter Tleson with signature ("Tleson, son of nearchos, made me"), c. 540 BC, now in the Munich State Collection of Antiquities

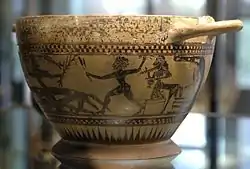

Lip cup by the potter Tleson with signature ("Tleson, son of nearchos, made me"), c. 540 BC, now in the Munich State Collection of Antiquities Band cup by an unknown artist showing fighters, c. 540 BC, from Vulci, now in the Louvre, Paris

Band cup by an unknown artist showing fighters, c. 540 BC, from Vulci, now in the Louvre, Paris Droop cup by an unknown artist, c. 550/530 BC, from Greece, now in the Louvre, Paris

Droop cup by an unknown artist, c. 550/530 BC, from Greece, now in the Louvre, Paris Kassel cup by an unknown artist, c. 540 BC, now in the Louvre, Paris

Kassel cup by an unknown artist, c. 540 BC, now in the Louvre, Paris

The last quarter of the 6th century BC

Until the end of the century the quality of black-figure vase production could basically be maintained. But after the development of the red-figure style around 530 BC, presumably by the Andokides Painter, more and more painters went over to the red-figure style, which provided many more possibilities for adding details within the figure contours. The new style also permitted many more promising experiments with foreshortening, perspective views and new designs for arrangements. Scene contents, as always, reflected trends in taste and the spirit of the times, but the red-figure style created better preconditions for presenting more elaborate scenes by exploiting the new arrangement possibilities.

But in the meantime, a few innovative craftsmen could still give new impulses to the production of black-figure vases. The most imaginative potter of the time, also a talented businessman, was Nikosthenes. Over 120 vases bear his signature, indicating that they were made by him or in his workshop. He seems to have particularly specialized in producing vases for export to Etruria. In his workshop the usual neck amphoras, Little Masters, Droop and eye cups were produced, but also a type of amphora reminiscent of Etruscan bucchero pottery, named the Nikosthenic amphora after its creator. These pieces were found particularly in Caere, the other vase types usually in Cerveteri and Vulci. The many inventions in his workshop were not limited to forms. In Nikosthenes’ workshop what is known as the Six's technique was developed, in which figures were painted in reddish brown or white atop a black glossy slip. It is not clear whether Nikosthenes also painted vases, in which case he is usually presumed to be identical with Painter N.[45] The BMN Painter and the red-figure Nikosthenes Painter are also named after Nikosthenes. In his workshop he employed many famous vase painters, including the elderly Lydos, Oltos and Epiktetos. The workshop tradition was continued by Nikosthenes’ successor, Pamphaios.[46]

Two black-figure vase painters are considered to be mannerists (540-520 BC). The painter Elbows Out decorated primarily Little Masters cups. The extended elbows of his figures are conspicuous, a characteristic responsible for his pragmatic name. He only seldom depicted mythological scenes; erotic scenes are much more common. He also decorated a rare vase form known as a lydion. The most important of the two painters was The Affecter, whose name comes from the exaggeratedly artificial impression made by his figures. These small-headed figures do not seem to be acting as much as posing. His early work shows scenes of daily life; later he turned to decorative scenes in which figures and attributes are recognizable, but hardly actions. If his figures are clothed they look as if they were padded; if they are naked they are very angular. The Affecter was both potter and painter; over 130 of his vases have survived.[47]

The Antimenes Painter (530–500 BC) liked to decorate hydria with animal friezes in the predella, and otherwise especially neck amphoras. Two hydria attributed to him are decorated on the neck region using a white ground technique. He was the first to paint amphoras with a masklike face of Dionysus. The most famous of his over 200 surviving vases shows an olive harvest on the back side. His drawings are seldom really precise, but neither are they excessively careless.[48] Stylistically, the painter Psiax is closely related to the Antimenes Painter, although the former also used the red-figure technique. As the teacher of the painters Euphronius and Phintias, Psiax had a great influence on the early development of the red-figure style. He frequently shows horse and chariot scenes and archers.[49]

The last important group of painters was the Leagros Group (520-500 BC), named after the kalos inscription they frequently used, Leagros. Amphoras and hydria, the latter often with palmettes in the predella, are the most frequently painted vessels. The image field is usually filled absolutely to capacity, but the quality of the images is still kept very high. Many of the over 200 vases in this group were decorated with scenes of the Trojan War and the life of Heracles[50] Painters like the witty Acheloos Painter, the conventional Chiusi Painter, and the Daybreak Painter with his faithful detailing belong to the Leagros Group.[51]

Other well-known vase painters of the time are the Painter of the Vatican Mourner, The Princeton Painter, the Painter of Munich 1410 and the Swing Painter (540-520 BC), to whom many vases are attributed. He is not considered to be a very good artist, but his figures are unintentionally humorous because of the figures with their large heads, strange noses and frequently clenched fists.[52] The work of the Rycroft Painter bears a resemblance to red-figure vase painting and the new forms of expression. He liked to depict Dionysian scenes, horses and chariots, and the adventures of Heracles. He often uses outline drawings. The approximately 50 usually large-size vessels attributed to him are elegantly painted.[53] The Class of C.M. 218 primarily decorated variations of the Nikosthenic amphoras. The Hypobibazon Class worked with a new type of belly amphora with rounded handles and feet, whose decoration is characterized by a key meander above the image fields. A smaller variant of neck amphora was decorated by the Three Line Group. The Perizoma Group adopted around 520 BC the newly introduced form of the stamnos. Toward the end of the century, high quality productions were still being produced by the Euphiletos Painter, the Madrid Painter and the imaginative Priam Painter.

Particularly cup painters like Oltos, Epiktetos, Pheidippos and Skythes painted vases in both red- and black-figure styles (Bilingual Pottery), primarily eye cups. The interior was usually in the black-figure style, the exterior in the red-figure style. There are several cases of amphoras whose front and back sides are decorated in the two different styles. The most famous are works by the Andokides Painter, whose black-figure scenes are attributed to the Lysippides Painter. Scholars are divided on the issue of whether these painters are the same person. Only a few painters, for example the Nikoxenos Painter and the Athena Painter, produced large quantities of vases using both techniques. Although bilingual pottery was quite popular for a short time, the style went out of fashion already toward the end of the century.[54]

Late Period

At the beginning of the 5th century BC until 480 BC at the latest, all painters of repute were using the red-figure style. But black-figure vases continued to be produced for some 50 additional years, with their quality progressively decreasing. The last painters producing acceptable quality images on large vases were the Eucharides Painter and the Kleophrades Painter. Only workshops which produced smaller shapes like olpes, oenochoes, skyphos, small neck amphoras and particular lekythos increasingly used the old style. The Phanyllis Painter used the Six technique, among other methods, and both the Edinburgh Painter and the Gela Painter decorated the first cylindrical lekythos. The former primarily produced casual, clear and simple scenes using a black-figure style on a white ground. The white ground of the vases was quite thick and no longer painted directly on the clay foundation, a technique which became the standard for all white-ground vases. The Sappho Painter specialized in funerary lekythos. The workshop of the Haimon Painter was especially productive; over 600 of their vases have survived. The Athena Painter (who is perhaps identical with the red-figure Bowdoin Painter) and the Perseus Painter continued to decorate large, standard lekythos. The scenes of the Athena Painter still radiate some of the dignity inherent in the work of the Leagros Group. The Marathon Painter is primarily known for the funerary lekythos found in the tumulus for the Athenians who died in the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC. The last significant lekythos painter, the Beldam Painter, worked from around 470 BC until 450 BC. Except for the Panathenaic prize amphoras, the black-figure style came to a close in Attica at this time.[55]

Panathenaic prize amphoras

Among black-figure Attic vases, the Panathenaic prize amphoras play a special role. After 566 BC—when the Panathenaic celebrations were introduced or reorganized—they were the prize for the winners of sport competitions and were filled with olive oil, one of the city's main export goods. On the front they routinely bore the image of the goddess Athena standing between two pillars on which roosters perched; on the back there was a sports scene. The shape was always the same and was only modified slightly over the long period of its production. The belly amphora was, as its name suggests, originally especially bulbous, with a short neck and a long, narrow foot. Around 530 BC the necks become shorter and the body somewhat narrower. Around 400 BC the vase shoulders were considerably reduced in width and the curve of the vase body looked constricted. After 366 BC the vases were again more elegant and become even narrower.

These vases were primarily produced in the leading workshops of the Kerameikos district. It seems to have been an honor or particularly lucrative to be awarded a commission for producing the vases. This also explains the existence of many prize amphoras by excellent vase painters. In addition to superior black-figure painters like the Euphiletos Painter, Exekias, Hypereides and the Leagros Group, many red-figure master craftsmen are known as creators of prize amphoras. These include the Eucharides Painter, the Kleophrades Painter, the Berlin Painter, the Achilleus Painter and Sophilos, who was the only one to have signed one of the surviving vases. The first known vase was produced by the Burgon Group and is known as the Burgon vase. Since the name of the ruling official (Archon) occasionally appears on the vase after the 4th century BC, some of the vases can be precisely dated. Since the Panathenaia were religious festivals, the style and the type of decoration changed neither during the red-figure period nor after figured vases were no longer really traded in Athens. The prize amphoras were produced into the 2nd century BC, and about 1,000 of them have survived. Since for some dates the number of amphorae awarded to a winner is known, it is possible to deduce that about one percent of the total production of Athenian vases has survived. Other projections lead to the conclusion that in all about seven million vases with painted figures were produced in Athens.[56] In addition to the prize amphoras, imitative forms known as Pseudo-Panathenaic prize amphoras were also manufactured.[57]

Laconia

Starting already in the 7th century BC painted pottery was being produced in Sparta for local consumption as well as for export. The first quality pieces were produced around 580 BC. The zenith in black-figure pottery was reached between about 575 and 525 BC. Besides Sparta, the main discovery sites are the islands of Rhodes and Samos, as well as Taranto, Etruscan necropolises, and Cyrene, which was at first considered to be the original source of the pottery. The quality of the vessels is very high. The clay was well slurried and was given a cream-colored coating. Amphoras, hydriai, column kraters (called krater lakonikos in antiquity), volute kraters, Chalcidic kraters, lebes, aryballoi and the Spartan drinking cup, the lakaina, were painted. But the index form and most frequent find is the cup. In Lakonia the deep bowl was usually put on a high foot; cups on low feet are rare. The exterior is typically decorated with ornaments, usually festoons of pomegranates, and the interior scene is quite large and contains figures. In Laconia earlier than in the rest of Greece the tondo became the main framework for cup scenes. The main image was likewise divided into two segments at an early date, a main scene and a smaller, lower one. Frequently the vessel was only coated with a glossy slip or decorated with just a few ornaments. Inscriptions are uncommon but can appear as name annotations. Signatures are unknown for potters as well as painters. It is probable that the Laconian craftsmen were perioeci pottery painters. Characteristic features of the pottery often match the fashion of known painters. It is also possible that they were migrant potters from eastern Greece, which would explain the strong eastern Greek influence especially on the Boreads Painter.

In the meantime at least eight vase painters can be distinguished. Five painters, the Arkesilas Painter (565–555), the Boreads Painter (575–565), the Hunt Painter, the Naucratis Painter (575–550) and the Rider Painter (550–530) are considered to be the more important representatives of the style, while other painters are regarded as craftsmen of lesser ability. The images are usually angular and stiff, and contain animal friezes, scenes of daily life, especially symposia, and many mythological subjects. Of the latter, Poseidon and Zeus are depicted especially frequently, but also Heracles and his twelve labors as well as the Theban and Trojan legend cycles. Especially on the early vases, a gorgon grimace is placed in a cup tondo. A depiction of the nymph Cyrene and a tondo with a rider with a scrolling tendril growing from his head (name vase of the Rider Painter) are exceptional.[58] Also important is a cup with an image of Arcesilaus II. The Arcesilas cup supplied the pragmatic name for the Arcesilas Painter.[59] It is one of the rare depictions on Greek pottery of current events or people. The subjects suggest Attic influence. A reddish purple was the main opaque color. At present over 360 Laconian vases are known, with almost a third of them, 116 pieces, being attributed to the Naucratis Painter. The decline around 550 BC of Corinthian black-figure vase painting, which had an important influence on Laconian painting, led to a massive reduction in the Laconian production of black-figure vases, which came to an end around 500 BC. The pottery was very widely distributed, from Marseille to Ionian Greece. On Samos, Laconian pottery is more common than Corinthian pottery because of the close political alliance with Sparta.[60]

Boeotia

Black-figure vases were produced in Boeotia from the 6th to the 4th century BC. As late as the early 6th century BC many Boeotian painters were using the orientalizing outline technique. Afterward they oriented themselves closely on Attic production. Distinctions and attributions to one of the two regions are sometimes difficult and the vases can also be confused with Corinthian pottery. Low-quality Attic and Corinthian vases are often declared to be Boeotian works. Frequently, good Boeotian vases are considered to be Attic and poor Attic vases are falsely considered to be Boeotian. There was probably an exchange of craftsmen with Attica. In at least one case it is certain that an Attic potter emigrated to Boeotia (the Horse-Bird Painter, and possibly also the Tokra Painter, and among the potters certainly Teisias the Athenian). The most important subjects are animal friezes, symposia and komos scenes. Mythological scenes are rare, and when present usually show Heracles or Theseus. From the late 6th century through the 5th century a silhouette-like style predominated. Especially kantharos, lekanis, cups, plates and pitchers were painted. As was the case in Athens, there are kalos inscriptions. Boeotian potters especially liked to produce molded vases, as well as kantharos with sculptured additions and tripod pyxides. The shapes of lekanis, cups and neck amphoras were also taken over from Athens. The painting style is often humorous, and there is a preference for komos scenes and satyrs.[61]

Between 425 and 350 BC Kabeiric vases were the main black-figure style in Boeotia. In most cases this was a hybrid form between a kantharos and a skyphos with a deep bowl and vertical ring handles, but there were also lebes, cups and pyxides. They are named after the primary place where they were found, the Sanctuary of the Kabeiroi near Thebes. The scenes, usually painted on only one side of the vase, depict the local cult. The vases caricature mythological events in a humorous, exaggerated form. Sometimes komos scenes are shown, which presumably related directly to the cult.[62]

Euboea

Black-figure vase painting in Euboea was also influenced by Corinth and especially by Attica. It is not always easy to distinguish these works from Attic vases. Scholars assume that most of the pottery was produced in Eretria. Primarily amphoras, lekythos, hydria and plates were painted. Large-format amphoras were usually decorated with mythological scenes, such as the adventures of Herakles or the Judgment of Paris. The large amphoras, derived from 7th century shapes, have tapering lips and usually scenes relating to weddings. They are apparently funerary vases produced for children who died before they could marry. Restrained employment of incising and regular use of opaque white for the floral ornaments were typical features of black-figure pottery from Eretria. In addition to scenes reflecting Attic models, there were also wilder scenes like the rape of a deer by a satyr or Heracles with centaurs and demons. The vases of the Dolphin Class were previously regarded as being Attic, but are now considered to be Euboic. However, their clay does not match any known Eretrian sources. Perhaps the pieces were produced in Chalcis.[63]

The origin of some black-figure regional styles is disputed. For example, Chalcidian pottery painting was once associated with Euboea; in the meantime production in Italy is considered to be more likely.

Eastern Greece

In hardly any other region of Greece are the borders between the orientalizing and black-figure styles as uncertain as in the case of vases from eastern Greece. Until about 600 BC only outline drawings and empty spaces were employed. Then during the late phase of the orientalizing style incised drawings began to appear, the new technique coming from northern Ionia. The animal frieze style which had previously predominated was certainly decorative, but offered few opportunities for further technical and artistic development. Regional styles arose, especially in Ionia.

Toward the end of the Wild Goat style, northern Ionian artists imitated—rather poorly—Corinthian models. But already in the 7th century high quality vases were being produced in Ionia. Since approximately 600 BC the black-figure style was used either entirely or in part to decorate vases. In addition to regional styles which developed in Klazomenai, Ephesus, Milet, Chios and Samos there were especially in northern Ionia styles which cannot be precisely localized. Oil flasks which adhered to the Lydian model (lydions) were common, but most of them were decorated only with stripes. There are also original scenes, for example a Scythian with a Bactrian camel, or a satyr and a ram. For some styles attribution is controversial. Thus the Northampton Group shows strong Ionian influence but production was probably in Italy, perhaps by immigrants from Ionia.[64]

In Klazomenai primarily amphoras and hydria were painted in the middle of the 6th century BC (c. 550 to 350 BC), as well as deep bowls with flat, angular-looking figures. The vessels are not very elegant in workmanship. Dancing women and animals were frequently depicted. Leading workshops were those of the Tübingen Painter, the Petrie Painter, and the Urla Group. Most of the vases were found in Naukratis and in Tell Defenneh, which was abandoned in 525 BC. Their origin was initially uncertain, but Robert Zahn identified the source by comparison with images on Klazomenian sarcophagi. The pottery was often decorated with sculptured women's masks. Mythological scenes were rare; fishscale ornaments, rows of white dots, and stiff-looking dancing women were popular. The depiction of a herold standing in front of a king and a queen is unique. In general, men were characterized by large, spade-shaped beards. Starting already in 600 BC and continuing to about 520 BC rosette cups, successor to the eastern Greece bird cups, were produced, probably in Klazomenai.[65]

Samian pottery first appeared around 560/550 BC with forms adopted from Attica. These are Little Masters cups and kantharos with facial forms. The painting is precise and decorative. Samos along with Milet and Rhodes was one of the main centers for the production of vases in the Wild Goat style.[66]

Rhodian vase painting is primarily known from Rhodian plates. These were produced using a polychrome technique with many of the details being incised as in black-figure painting. From about 560 to 530 BC situlas were common, inspired by Egyptian models. These show both Greek subjects, such as Typhon, as well as ancient Egyptian themes like Egyptian hieroglyphics and Egyptian sport disciplines.[67]

Italy including Etruria

Caeretan Hydria

"Caeretan hydria" is the name used for an especially colorful style of black-figure vase painting. The origin of these vases is disputed in the literature. Based on an assessment of the painting the vases were long considered to be Etruscan or Corinthian, but in recent years the view predominates that the producers were two pottery painters who emigrated from eastern Greece to Caere (modern Cerveteri) in Etruria. Inscriptions in Ionic Greek support the emigration theory. The workshop existed for only one generation. Today about 40 vases produced by the two master craftsmen in this style are known. All are hydriai except for one alabastron. None were found outside of Etruria; most came from Caere, which is the reason for their name. The vases are dated to approximately 530 to 510/500 BC. The Caeretan hydria are followed stylistically by neck amphoras decorated with stripes.

These technically rather inferior hydriai are 40–45 cm. high. The bodies of these vases have high and very prominent necks, broad shoulders, and low ring feet in the form of upside-down chalices. Many of the hydriai are misshapen or show faulty firing. The painted images are in four zones: a shoulder zone, a belly zone with figures and one with ornaments, and a lower section. All but the belly zone with figures are decorated with ornaments. There is only one case of both belly friezes having figures. Their multiple colors distinguish them from all other black-figure styles. The style recalls Ionian vase painting and multicolored painted wooden tablets found in Egypt. Men are shown with red, black or white skin. Women are almost always portrayed with an opaque white color. The contours as well as the details are incised, as is typical for the black-figure style. Surfaces of black glossy slip are often covered with an additional colored slip, so that the black slip which becomes visible where there is scoring supplies the various shapes with internal details. On the front side the images are always full of action, on the back heraldic designs are common. Ornaments are an important component of the hydrias; they are not subsidiary to other motifs. Stencils were used to paint the ornaments; they are not incised.

The Busiris Painter and the Eagle Painter are named as painters. The latter is considered the leading representative of this style. They were particularly interested in mythological topics which usually revealed an eastern influence. On the name vase by the Busiris painter, Heracles is trampling on the mythical Egyptian pharao Busiris. Heracles is frequently depicted on other vases as well, and scenes of daily life also exist. There are also uncommon scenes, such as Cetus accompanied by a white seal.[68]

Pontic vases

The Pontic vases are also closely related stylistically to Ionian pottery painting. Also in this case it is assumed that they were produced in Etruscan workshops by craftsmen who emigrated from Ionia. The vases got their misleading name from the depiction on a vase of archers thought to be Scythians, who lived at the Black Sea (Pontus). Most of the vases were found in graves in Vulci, a significant number also in Cerveteri. The index form was a neck amphora with a particularly slender shape, closely resembling Tyrrhenian amphoras. Other shapes were oenochoes with spiral handles, dinos, kyathos, plates, beakers with high bases, and, less often, kantharos and other forms. The adornment of Pontic vases is always similar. In general there is an ornamental decoration on the neck, then figures on the shoulder, followed by another band of ornaments, an animal frieze, and finally a ring of rays. Foot, neck and handles are black. The importance of ornaments is noticeable, although they are often rather carelessly formed; some vases are decorated only with ornaments. The clay of these vases is yellowish-red; the slip covering the vases is black or brownish-red, of high quality, and with a metallic sheen. Red and white opaque colors are generously used for figures and ornaments. Animals are usually decorated with a white stripe on their bellies. Scholars have identified six workshops to date. The earliest and best is considered to be that of the Paris Painter. He shows mythological figures, included a beardless Heracles, as was customary in eastern Greece. Occasionally there are scenes which are not a part of Greek mythology, such as Heracles fighting Juno Sospita ("the Savior") by the Paris Painter, or a wolf demon by the Tityos Painter. There are also scenes of daily life, komos scenes, and riders. The vases are dated to a time between 550 and 500 BC, and about 200 are known.[69]

Etruria

Locally produced Etruscan vases probably date from the 7th century BC. At first, they resemble black-figure models from Corinth and eastern Greece. It is assumed that in the early phase primarily Greek immigrants were the producers. The first important style was Pontic pottery painting. Afterward, in the period between 530 and 500 BC, the Micali Painter and his workshop followed. At this time Etruscan artists tended to follow Attic models and produced primarily amphoras, hydriai and jugs. They usually had komos and symposia scenes and animal friezes. Mythological scenes are less common, but they are very carefully produced. The black-figure style ended around 480 BC. Toward the end a mannerist style developed, and sometimes a rather careless silhouette technique.[70]

Chalcidian pottery

Chalcidian vase painting was named from the mythological inscriptions which sometimes appeared in Chalcidian script. For this reason the origin of the pottery was first suspected to be Euboea. Currently it is assumed that the pottery was produced in Rhegion, perhaps also in Caere, but the issue has not yet been finally decided.[71] Chalcidian vase painting was influenced by Attic, Corinthian and especially Ionian painting. The vases were found primarily in Italian locations like Caeri, Vulci and Rhegion, but also at other locations of the western Mediterranean.

The production of Chalcidian vases began suddenly around 560 BC. To date, no precursors have been identified. After 50 years, around 510 BC, it was already over. About 600 vases have survived, and 15 painters or painter groups have been so far identified. These vases are characterized by high quality pottery work. The glossy slip which covers them is usually pitch-black after firing. The clay has an orange color. Red and white opaque colores were generously used in the painting, as was scoring to produce interior details. The index form is the neck amphora, accounting for a quarter of all known vases, but there are also eye cups, oinochoes and hydria; other vessel types being less common. Lekanis and cups in the Etruscan style are exceptions. The vases are economical and stringent in construction. The "Chalcidian cup foot" is a typical characteristic. It is sometimes copied in black-figure Attic vases, less often in red-figured vases.

The most important of the known artists of the older generation is the Inscription Painter, of the younger representatives the Phineus Painter. The former is presumably the originator of the style; some 170 of the surviving vases are attributed to the very productive workshop of the latter. He is probably also the last representative of this style. The images are usually more decorative than narrative. Riders, animal friezes, heraldic pictures or groups of people are shown. A large lotus-palmette cross is frequently part of the picture. Mythological scenes are seldom, but when they occur they are in general of exceptionally high quality.

Pseudo-Chalcidian vase painting is the successor to Chalcidian painting. It is close to Chalcidian but also has strong links to Attic and Corinthian vase painting. Thus the artists used the Ionian rather than the Chalcidian alphabet for inscriptions. The structure of the clay is also different. There are about 70 known vases of this type, which were first classified by Andreas Rumpf. It is possible that the artisans were successors to the Chalcidian vase painters and potters who emigrated to Etruria.[72]

Pseudo-Chalcidian vase painting is classified into two groups. The elder of the two is the Polyphemus Group, which produced most of the surviving vessels, primarily neck amphoras and oinochoes. Groups of animals are usually shown, less seldom mythological scenes. The vessels were found in Etruria, on Sicily, in Marsellle and Vix. The younger and less productive Memnon Group, to which 12 vases are currently attributed, had a much smaller geographical distribution, being limited to Etruria and Sicily. Except for one oinochoe they produced only neck amphoras, which were usually decorated with animals and riders.[73]

Other

The vases of the Northampton Group were all small neck amphoras with the exception of a single belly amphora. They are stylistically very similar to northern Ionian vase painting, but were probably produced in Italy rather than in Ionia, perhaps in Etruria around 540 BC. The vases of this group are of very high quality. They show rich ornamental decorations and scenes that have captured the interest of scholars, such as a prince with horses and someone riding on a crane. They are similar to the work of the Group of Campana Dinoi and to the so-called Northampton Amphora whose clay is similar to that of Caeretan hydriai. The Northampton Group was named after this amphora. The round Campana hydriai recall Boeotian and Euboean models.[74]

Other regions

Alabastrons with cylindrical bodies from Andros are rare, as are lekanis from Thasos. These are reminiscent of Boeotian products except that they have two animal friezes instead of the single frieze common for Boeotia. Thasian plates rather followed Attic models and with their figured scenes are more ambitious than on the lekanis. Imitations of vases from Chios in the black-figure style are known. Local black-figure pottery from Halai is also rare. After the Athenians occupied Elaious on the Dardanelles, local black-figure pottery production began there as well. The modest products included simple lekanis with outline images. A small number of vases in black-figure style were produced in Celtic France. They too were almost certainly inspired by Greek vases.[75]

Research and reception

Scholarly research on these vases started especially in the 19th century. Since this time the suspicion has intensified that these vases have a Greek rather than an Etruscan origin. Especially a Panathenaic prize amphora found by Edward Dodwell in 1819 in Athens provided evidence. The first to present a proof was Gustav Kramer in his work Styl und Herkunft der bemalten griechischen Tongefäße (1837). However it took several years for this insight to be generally accepted. Eduard Gerhard published an article entitled Rapporto Volcente in the Annali dell’Instituto di Corrispondenza Archeologica in which he systematically investigated the vases; he was the first scholar to do so. Toward this end in 1830 he studied vases found in Tarquinia, comparing them, for example, with vases found in Attica and Aegina. During this work he identified 31 painter and potter signatures. Previously, only the potter Taleides was known.[76]

The next step in research was scientific cataloging of the major vase collections in museums. In 1854 Otto Jahn published the vases in the Munich State Collection of Antiquities. Previously, catalogs of the Vatican museums (1842) and the British Museum (1851) had been published. The description of the vase collection in the Berlin Collection of Classical Antiquities, put together in 1885 by Adolf Furtwängler, was especially influential. Furtwängler was the first to classify the vessels by region of artistic origin, technology, style, shape, and painting stye, which had a lasting effect on subsequent research. In 1893 Paul Hartwig attempted in his book Meisterschalen to identify various painters based on kalos inscriptions, signatures and style analyses. Edmond Pottier, curator at the Louvre, initiated in 1919 the Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum. All major collections worldwide are published in this series, which as of 2009 amounted to over 300 volumes.[77]

Scientific research on Attic vase painting owes a great deal to John D. Beazley. He began studying these vases in about 1910, making use of the method developed by the art historian Giovanni Morelli for studying paintings, which had been refined by Bernard Berenson. He assumed that each painter created original works which could always be unmistakably attributed. He made use of particular details such as faces, fingers, arms, legs, knees, and folds of clothing. Beazley studied 65,000 vases and fragments, of which 20,000 were black-figure. In the course of his studies, which lasted almost six decades, he could attribute 17,000 of them by name or by using a system of pragmatic names, and classified them into groups of painters or workshops, relationships and stylistic affinity. He identified over 1,500 potters and painters. No other archaeologist had such a decisive influence on the research of an archaeological field as did Beazley, whose analyses remain valid to a large extent up to the present time. After Beazley, scholars like John Boardman, Erika Simon and Dietrich von Bothmer investigated black-figure Attic vases.[78]

Basic research on Corinthian pottery was accomplished by Humfry Payne, who in the 1930s made a first stylistic classification which is, in essence, being used up to the present time. He classified the vases according to shape, type of decoration and image subjects, and only afterward did he make distinctions as to painters and workshops. He followed Beazley's method except for attributing less importance to allocating painters and groups since a chronological framework was more important for him. Jack L. Benson took on this allocation task in 1953 and distinguished 109 painters and groups. Last of all, Darrell A. Amyx summarized the research up to that point in his 1988 book Corinthian Vase-Painting of the Archaic Period. It is however a matter of scholarly dispute whether it is at all possible in the case of Corinthian pottery to attribute specific painters.[79]

Laconian pottery was known since the 19th century from a significant number of vases from Etruscan graves. At first they were erroneously attributed, being considered for a long time to be a product of Cyrene, where some of the earliest pieces were also found. Thanks to British excavations carried out in Sparta's Sanctuary of Artemis Orthia, their true origin was quickly identified. In 1934, Arthur Lane put together all the known material and was the first archaeologist to identify different artists. In 1956 the new discoveries were studied by Brian B. Shefton. He reduced the number of distinct painters by half. In 1958 and 1959 other new material from Taranto was published. A significant number of other vases were also found on Samos. Conrad Michael Stibbe studied anew all 360 vases known to him and published his findings in 1972. He identified five major and three minor painters.[80]

In addition to research on Attic, Corinthian and Laconian vase painting, archaeologists are frequently especially interested in minor Italian styles. The Caeretan hydriai were first identified and named by Carl Humann and Otto Puchstein. Andreas Rumpf, Adolf Kirchhoff and other archaeologists erroneously suspected the origin of Chalkidischen Pottery to be Euboea. Georg Ferdinand Dümmler is responsible for the false naming of the Pontic vases, which he assumed to come from the Black Sea area because of the depiction of a Scythian on one of the vases.[81] In the meantime, research on all styles is carried out less by individuals than by a large international group of scientists.

See also

- List of Greek Vase Painters § Black Figure Period

- Pottery of Ancient Greece

- See also w:de:Liste der Formen, Typen und Varianten der antiken griechischen Fein- und Gebrauchskeramik in the German Wikipedia for a useful set of tables classifying vase shapes and variations, with distinguishing shape outlines and typical examples.

- See also w:de:Liste der griechischen Töpfer und Vasenmaler/Konkordanz

References

- ↑ On vase production and style see Ingeborg Scheibler: Griechische Töpferkunst. München 1995, S. 73–134; Matthias Steinhart: Töpferkunst und Meisterzeichnung, von Zabern, Mainz 1996, S. 14–17; Heide Mommsen, Matthias Steinhart: Schwarzfigurige Vasenmalerei. In: Der Neue Pauly (DNP). Band 12, Metzler, Stuttgart 1996–2003, ISBN 3-476-01470-3, Sp. 274–281.

- ↑ "Black-figure." In Encyclopedic Dictionary of Archaeology. Barbara Ann Kipfer, ed. New York: Springer, 2000, p. 71. ISBN 0-306-46158-7;Ashmolean Museum Department of Antiquities. Select Exhibition of Sir John and Lady Beazley's Gifts to the Ashmolean Museum, 1912-1966. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 1967, p. 40; Grant, Neil. The Greeks: How They Lived. New York: Mallard Press, 1990, p. 18. ISBN 0-7924-5383-2

- ↑ On Corinthian vase paintings see Thomas Mannack: Griechische Vasenmalerei, Theiss, Stuttgart 2002, S. 100–104; Matthias Steinhart: Korinthische Vasenmalerei. In: Der Neue Pauly (DNP). Band 6, Metzler, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-476-01476-2, Sp. 738–742.; John Boardman: Early Greek Vase Painting, Thames and Hudson, London 1998, S. 178–185. .

- ↑ Chronologies vary somewhat. In Matthias Steinhart: Korinthische Vasenmalerei. In: Der Neue Pauly (DNP). Band 6, Metzler, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-476-01476-2, Sp. 738–742 the following is given: Early Corinthian (620/615–595 BC), Middle Corinthian (595–570 BC), Late Corinthian I (570–550 BC), and Late Corinthian II (after 550 BC).

- ↑ On the Dodwell Painter, see Matthias Steinhart: Dodwell-Maler. In: Der Neue Pauly (DNP). Band 3, Metzler, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-476-01473-8, Sp. 726–727.

- ↑ On the Cavalcade Painter, see Matthias Steinhart: Kavalkade-Maler. In: Der Neue Pauly (DNP). Band 6, Metzler, Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-476-01476-2, Sp. 370–371.

- ↑ Mannack, S. 101.

- ↑ today in Basel.

- ↑ On Tomonidas see Matthias Steinhart: Timonidas. In: Der Neue Pauly (DNP). Band 12/1, Metzler, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 3-476-01482-7, Sp. 594–594.

- ↑ Now in Athens.

- ↑ Now in the Berlin Collection of Classical Antiquities, Altes Museum.

- ↑ On Chares see Matthias Steinhart: Chares [5]. In: Der Neue Pauly (DNP). Band 2, Metzler, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-476-01472-X, Sp. 1099–1099.

- ↑ On the Tydeus Painter see Matthias Steinhart: Tydeus-Maler. In: Der Neue Pauly (DNP). Band 2, Metzler, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-476-01472-X, Sp. 939–940.

- ↑ John Boardman: Schwarzfigurige Vasen aus Athen, von Zabern, Mainz 1979, S. 7.

- ↑ Heide Mommsen: Schwarzfigurige Vasenmalerei. In: Der Neue Pauly (DNP). Band 12, Metzler, Stuttgart 1996–2003, ISBN 3-476-01470-3, Sp. 274–281.

- ↑ Thomas Mannack: Griechische Vasenmalerei, Theiss, Stuttgart 2002, S. 104.

- ↑ Fragment in Leipzig, found in Cerveteri, with gorgons on the belly as on the Nessos vase.

- ↑ Thomas Mannack: Griechische Vasenmalerei, Theiss, Stuttgart 2002, S. 105; John Boardman: Schwarzfigurige Vasen aus Athen, von Zabern, Mainz 1979, S. 18f.

- ↑ John Boardman: Schwarzfigurige Vasen aus Athen, von Zabern, Mainz 1979, S. 20.

- ↑ Found on the Akropolis in Athens, now in the Akropolis Museum, inventory number 587.

- ↑ John Boardman: Schwarzfigurige Vasen aus Athen, von Zabern, Mainz 1979, S. 21.

- ↑ Thomas Mannack: Griechische Vasenmalerei, Theiss, Stuttgart 2002, S. 111.

- ↑ on the François vase see John Boardman: Schwarzfigurige Vasen aus Athen, von Zabern, Mainz 1979, S. 37f. und Thomas Mannack: Griechische Vasenmalerei, Theiss, Stuttgart 2002, S. 111f.

- ↑ Thomas Mannack: Griechische Vasenmalerei, Theiss, Stuttgart 2002, S. 113.

- ↑ On Lydos see John Boardman: Schwarzfigurige Vasen aus Athen, von Zabern, Mainz 1979, S. 57–58, Thomas Mannack: Griechische Vasenmalerei, Theiss, Stuttgart 2002, S. 113.

- ↑ John Boardman: Schwarzfigurige Vasen aus Athen, von Zabern, Mainz 1979, S. 57.

- ↑ John Boardman: Schwarzfigurige Vasen aus Athen, von Zabern, Mainz 1979, S. 60.

- ↑ John Boardman: Schwarzfigurige Vasen aus Athen, von Zabern, Mainz 1979, S. 61.

- ↑ On the Amasis Painter see John Boardman: Schwarzfigurige Vasen aus Athen, von Zabern, Mainz 1979, S. 60–62; Thomas Mannack: Griechische Vasenmalerei, Theiss, Stuttgart 2002, S. 120.

- ↑ Quote translated from John Boardman: Schwarzfigurige Vasen aus Athen, von Zabern, Mainz 1979, S. 62. On Group E see John Boardman: Schwarzfigurige Vasen aus Athen, von Zabern, Mainz 1979, S. 62 und Thomas Mannack: Griechische Vasenmalerei, Theiss, Stuttgart 2002, S. 120.