| St Mary’s Hospital or Bishop Dunbar’s Hospital | |

|---|---|

| St Machar's Cathedral | |

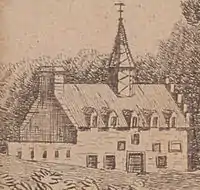

Sketch of Dunbar's Hospital: from Alexander Macdonald Munro, and New Spalding Club (Aberdeen Scotland), Records of Old Aberdeen, Mclvii-Mdcccxci (Mcccxcviii-Mcmiii) Vol. 2. (Aberdeen: Printed for the New Spalding Club, 1899). - Unknown author. | |

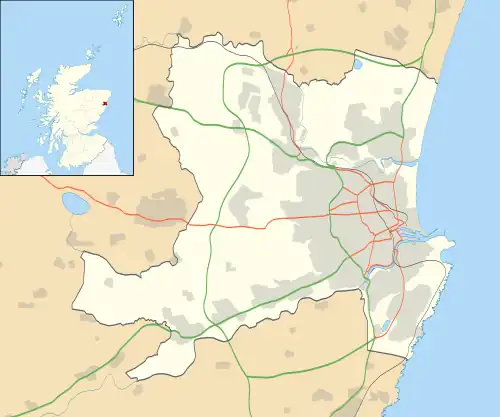

Location in Aberdeen | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Old Aberdeen, Aberdeenshire, Scotland |

| Coordinates | 57°10′12″N 2°06′12″W / 57.169956°N 2.1034351°W |

| Organisation | |

| Care system | Medieval Sub-Monastic care |

| Type | Medieval Cathedral Hospital |

| Patron | Gavin Dunbar (bishop of Aberdeen) |

| History | |

| Opened | 1531 |

| Closed | c. 1789 |

| Demolished | After 1790 |

| Links | |

| Lists | Hospitals in Scotland |

| Other links | Hospitals in medieval Scotland |

Bishop Dunbar's Hospital was founded in 1531 by Bishop Gavin Dunbar, the Elder. The hospital was endowed by a mortification just before his death. Dunbar petitioned the King, James V of Scotland, and the charter, signed on 24 February 1531 records the King’s approval that ‘[Dunbar shall] ... found an hospital near the cathedral church, but outside the cemetery...’ It was also known as St Mary's Hospital.[1] In the mortification, Dunbar's charitable purpose is recorded.[2] Bedesmen were supported by a charitable foundation that emerged from the original church control until the twenty-first century. Bedesmen drew their name from the word "bede" - a prayer. The residents of Dunbar's Hospital said prayers in a cycle of Divine Office. The Bede House, Old Aberdeen was used by the Bedesmen from the hospital from 1789 to the end of the nineteenth century. The only remains of the 1531 building can be seen in a perimeter wall for Seaton Park in Old Aberdeen. The last Bedesman died in 1988. The Managers of the Hospital constituted a Charity, Bishop Dunbar Hospital Trust. The Charity ceased active operation in 2012.

Foundation of the hospital

There are a number of copies of the foundation charter in the Dunbar Archives at the University of Aberdeen.[3] An English translation at the beginning of the charter is as follows:

“…It is quite evident that all prelates of the church are not the owners of the patrimony of the cross (or the Christian church), but the guardians and dispensers of it. And whatever is left of the fruits of the church to any prelate after satisfying the necessities of the church and his own life, the prelate is bound to bestow it on the poor, and devote it to pious purposes. And although we have given away in different churches for the augmentation of divine worship some parts of our means, acquired by industry or otherwise, and other parts for the welfare of the state, yet we have contributed to charitable works at great expense. Feeling that when something is left, after supplying the needs of the church and our own life, and remembering the words of almighty God :- ‘Give of thy bread to the hungry, and take the poor and the wandering under the shelter of thy house, and clothe the naked…”

In this preface, Dunbar confirms his Christian practice of enacting "corporal works of mercy".[4] However, this does not really explain fully why the hospital was built. Dunbar was a charitable man. It was common practice for the nobility to exercise care of their community. Some noblemen were more charitable than others. Perhaps it was because Dunbar was a Bishop? It is possible that there was a theological motive at work. The explanation is to be found in the name of the inhabitants, Bedesmen, and in the description of how they were to live – in care and prayer. The explanation draws on an often-misunderstood principle of Catholicism – a belief in Purgatory and prayers for the dead.[5]

“… we desire therefore, by means of a new charitable institution, to obtain some help towards earning divine favour [author’s emphasis] by relieving the want of the Christian poor, and supporting them, and we have resolved to make, construct, and found a hospital near the cathedral … but outside the cemetery, and to form and endow it in the following manner…”

Dunbar makes explicit his wish to ‘…[earn] … divine favour by relieving the want of the Christian poor…’ In this and in other acts, Bishop Dunbar’s Catholic faith in salvation is clear. He expresses a belief in prayers for the dead and a certainty in the cleansing power of Purgatory.[6] To the late medieval Catholic, Purgatory was as ‘real’ as Heaven or Hell or pestilence or the existence of most of the population in poverty. Dunbar as a prelate of the Church would have held what Karen Armstrong calls a ‘mythic’ belief in the practice of saying prayers for the dead.[7] Dunbar was acting with dual purposes – to alleviate poverty and to exhibit Christian charity. His hospital was to support Bedesmen who were to pray for the dead. There can be no doubt that Dunbar aimed to deal with the poverty of some elderly (men) in Old Aberdeen. It is clear that his concerns regarding poverty were based on a Catholic faith in salvation. The charter continues:

“… In the first place we have ordained that the house of the hospital shall be a hundred feet long, and about thirty-two feet wide, and that it shall be divided so as to accommodate twelve poor men in separate rooms…the rest of the house, which will be thirty-six feet long, and thirty-two feet wide, will be so divided, that in the north side there will be a common room sixteen wide, and thirty-six feet long, for all the poor men in which they can have a common fire and other necessary things, and opposite to it, in the south side of the house, there will be an oratory well furnished and of the same size as the common room of the house, and provided with an altar…”

that is, a concern for the poverty of elderly men in a dedicated home and Christian piety in the provision of an oratory. The prayerful day became less strict from 1577-80. From 1545 to 1577, William Gordon (Bishop of Aberdeen) was Bishop of Aberdeen. Gordon and his nephew, the staunchly Catholic George Gordon, 4th Earl of Huntly were slow to acquiesce to the wishes of the Reformist and the "Church of Scotland". After the downfall of Mary, Queen of Scots, in 1567, Bishop Gordon appears to have accepted the authority of the new Church of Scotland since he retained his see until his death on 6 August 1577. It is likely that the strict regime of prayer required of the Bedesmen was continued until Bishop Gordon’s death. His successor was David Cunningham (bishop) who managed to negotiate an understanding between James VI and the 4th Earl of Huntly. The status of the Bedesmen changed during the time Cunningham was "Bishop" and Chancellor of Kings College, Old Aberdeen and became less Catholic during the time he held the Bishopric of Aberdeen. At the time the Reformation in Old Aberdeen was a "slow process". The Reformation affected the relationship between the Hospital and the Cathedral Church of St Machar. The status of "bedesmen" varied across different institutions. In "new" Aberdeen, in 1633, Dr William Guild had a mortification ratified by King Charles I, that instituted a Hospital for ‘… good pious and sober men…’, members of the Seven Incorporated Trades of Aberdeen. See Aberdeen trades hospitals. The Mortification required the men to live a Reformed yet prayerful day. The men were to be:

‘…always present at the Sunday and weekly sermons … unless they be confined to their beds by sickness .. , as also at the public morning and evening prayers .. especially in summer. ALSO, I ordain that in their own chapel a portion of the Word of God be read twice daily, and prayers offered up by a suitable reader … who shall have fifty merks paid him therefore yearly … to be properly chosen by the patron, which service shall be between nine and ten in the morning or forenoon, and between three and four in the evening or afternoon: and whoever .. except through sickness … shall be once absent, let him be admonished; if twice, punished by the director; and if thrice, removed from the hospital…’ (1887 translation)

A dutiful prayer-full day was to be observed, under penalty of exclusion, in post-Reformation Aberdeen.[8]

The Dunbar Hospital Charter describes how the men were to be paid, fed and clothed; and how the hospital was to be organized and lays down details of the prayerful day the Bedesmen were to keep:

“...the poor men shall pray daily for the felicitous and prosperous state of our lord the King, and for his soul, and for the souls of his predecessors and successors, and also for our soul, and the souls of our parents, our brothers and sisters, and all our friends, and also of all the faithful in Christ …”

The prayerful day was long. Based on our modern understanding of a care home, the conditions were arduous.

“….between supper time and the closing of the gate, the poor men shall enter the oratory and every one in his place in a line shall repeat devoutly the hymn of our Lady on behalf of the souls of those before mentioned. Then if so disposed, they may go away and sleep till three o'clock, when every poor man shall repeat in his room the hymn of the most blessed Virgin Mary …”

The Charter can be read in a number of ways. It is a prescient description of care for the poor and the elderly, which was not to be fully enacted in Scotland until the nineteenth century. In this Bishop Dunbar was a caring and prophetic prelate. The Charter can also be read as a document of the times. In late pre-Reformation Scotland Dunbar, the King, the Court and the vast majority of people would have found nothing amiss in endowing men and women to pray for the dead. Dunbar in his civic and religious acts was a clearly a man of his times. He was a Canonist and Catholic priest who had a firm grasp on a theory of salvation. He placed an unambiguous belief in the power of prayer to mitigate the purging of his soul before its eventual and certain elevation into Paradise. It is a truism that charity brings with it a responsibility to enact Christian values.

The Hospital

Very little is known about the exact conditions of the Hospital. The earliest drawings are in accord with the 1531 Mortification. William Orem, the Old Aberdeen Town Clerk, writing in 1725 provides some details:

“ …Above the gate is an inscription “PER EXECUTORES” and on the south side of the ..oratory another inscription, viz. Duodecim pauperibus domum hanc Reverendus Paper Gavinus Dunbar hujius alme sedis quondam pontifex aedisicari jussit anno a Christo nato 1532”. [Trans. Gavin Dunbar, reverend Father in God, who was sometime Bishop of this holy see, ordered this house to be built for twelve poor men, anno 1532 – Glory To God] Within the Oratory there is an further dedication (which includes) .. “Gloria episcopi est pauperum opibis providere. Ignominia sacerdotis est proprijs studere divitijs Patientia pauperum non perbit in sinem..” [ Trans. ..It is the glory of the Bishop to provide for the poor but a reproach to a priest to study only how to make himself rich. The Lord will not suyffer the poor to perish..][10] The armorial costs of King James V are on the south side of the Hospital along with that of Bishop Dunbar. “.. in the said Oratory there is a desk for a chaplain, and seats also for the said poor men; and a little baptizary in the south wall thereof. …”(pp63-64)[11]

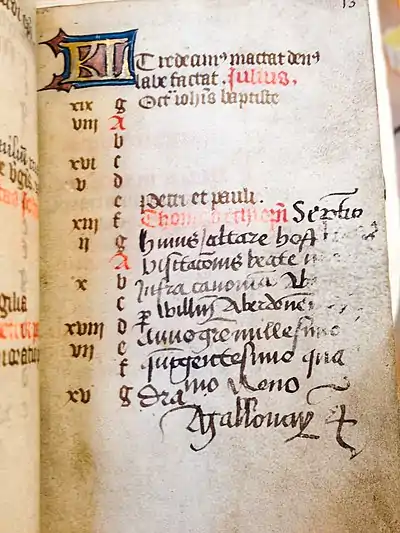

The Altar of St. Thomas the Martyr of Canterbury

One item survives from the Oratory. This is the Aberdeen Psalter. It is annotated by Bishop Dunbar’s distinguished colleague Canon Alexander Galloway. Galloway often annotated liturgic books. The annotation has been written in 1549, at the reference in the calendar to 7 July. In 1549 William Gordon (bishop of Aberdeen) was bishop. This annotation refers to an altar dedicated to St Thomas of Canterbury. It reads "….huius altare hospitalis visitationis beate Marie infra canonicam Aberdonensem per Willelmum Aberdonensem episcopum anno gratie millesimo quingentesimo quadragesimo nono..." The insertion is damaged and there must be some doubt about the date when the altar was erected. It is most likely that the altar was erected by Bishop Dunbar c. 1529x1531, not by Bishop Gordon.[12] It seems likely that one of the altars in the Oratory would have been dedicated to Thomas of Canterbury, given that Dunbar was had dedicated another altar to a St Thomas in Elgin Cathedral on 2 September 1529. This altar, along with two chaplains and 50 merks income from the lands of Querrelwood and Lidgate, was to commemorate his father and mother.[13]

The Move to Don Street

In about 1789, the original building was in a state of disrepair and the owner of the land adjacent to the Hospital and St Machar’s Cathedral Church, James Forbes-Seaton arranged for a house he owned in Seaton Gate (modern Don Street) to be used for the Bedesmen. In that year the Bedesmen moved away from the original Hospital and it was in a state of ruins with a few years. See Bede House, Old Aberdeen for the history of the Bede House in Old Aberdeen.

Later history

From about the 1830s the Bedesmen began to live in the community instead of the Bede House in Don Street. Similar changes occurred in the "new" Aberdeen Trades Hospital. See Aberdeen trades hospitals. The number of men had increased and the income to support them had diminished. The decline in the use of in-house residential care as well as the "prayerful day" was complete.

The Last Bedesman

The charitable aims of the Hospital lasted until the 21st century. The last Bedesman died in 1988. The charity, Bishop Dunbar’s Hospital Trust, continued support the elderly poor in Old Aberdeen through the 19th and 20th centuries. With declining income from investments, the charity was eventually wound up in 2009. The name Bede is still commemorated in Old Aberdeen in a community housing development, Bedehouse Court.

See also

- Beggar's badge

- Hospitals in medieval Scotland

- Aberdeen trades hospitals

- Mitchell's Hospital Old Aberdeen

- Kincardine O'Neil Hospital, Aberdeenshire

- Scottish Bedesmen

- Hospital chantry

- Hospital of St John the Baptist, Arbroath

- Soutra Aisle

- Physic garden

- Provand's Lordship - the "physic" garden in Glasgow

A much later hospital was built in Old Aberdeen - see Mitchell's Hospital Old Aberdeen in 1801.

References

- ↑ Ian Borthwick Cowan, David Edward Easson, and Richard Neville Hadcock, Medieval Religious Houses, Scotland with an Appendix on the Houses in the Isle of Man. 2nd edn (London: Longman, 1976), pp. xxviii, 252p,[4]fold plates.

- ↑ "..FRANGE ESURIENTI PANEM TUUM ET EGENOS VAGOSQUE INDUC IN DOMUM TUAM.." (give thy bread to the hungry and the needy and bring the wandering into your house).

- ↑ See MS 3861 for further details of the Hospital Archive

- ↑ P K Guilday and others, The Catholic Encyclopaedia, Rev ed (Gilmary Society, New York, 1936). See Matthew 25:34-40 "… Verily I say unto you, in as much as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me…" (v.40, King James Version). In Catholic theology corporal works of mercy are: to feed the hungry; to give drink to the thirsty; to clothe the naked; to harbour the harbourless; to visit the sick; to ransom the captive; and, to bury the dead.

- ↑ See John A. A. Goodall, God's House at Ewelme : Life, Devotion, and Architecture in a Fifteenth-Century Almshouse, (Aldershot, Hants, England ; Burlington, Vt.: Ashgate, 2001). Goodall’s book is an excellent account of a Bedehouse or Almshouse built in 1437 by Alice, Duchess of Suffolk. There is a striking similarity in the prayerful day to be followed by the almsmen and Dunbar’s Bedesmen. Goodall provides a summary of the theology under-pinning Purgatory (pp.142-145). It is worth comparing the text of the Ewelme charter with the charter from St Mary’s in Old Aberdeen (see pp.234-237, lines 522 to 743, in the English translation of the Ewelme charter).

- ↑ There are other examples of Dunbar’s belief in Purgatory. For example, on 2 September 1529, he endowed two Chaplains for the Cathedral in Elgin to ‘… pray for the Souls …’ of his father and mother. Cosmo Innes, Bannatyne Club (Edinburgh Scotland), and Episcopal Church in Scotland. Diocese of Moray., Registrum Episcopatus Moraviensis E Pluribus Codicibus Consarcinatum Circa A.D. Mccc, Cum Continuatione Diplomatum Recentiorum Usque Ad A.D. Mdcxxiii, (Edinburgi: [Bannatyne Club], 1837).

- ↑ K Armstrong, The case for God: what religion really means (Bodley Head, 2009); K Armstrong, A short history of myth (Canongate, Edinburgh, 2005); K Armstrong and others, The myths. 6 vols (Canongate, Edinburgh, 2008). Armstrong in her recent writing, distinguishes between ‘mythos’ and ‘logos’. ‘Mythos’ from Greek..[μύθος] ‘…refers to experiences that are obscure and ineffable because they are beyond speech and relate to the inner rather than the external world; "logos" from Greek (λόγος)… corresponds to facts… it is essentially practical … it constantly looks ahead to achieve a greater control over our environment or to discover something fresh…’ She argues persuasively that in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries people began to move from a belief system that was based on ‘mythos’ ‘….to develop an entirely new kind of civilization governed by scientific rationality…’ She calls these beliefs ‘logos’.

- ↑ See Ebenezer Bain, Merchant and Craft Guilds : A History of the Aberdeen Incorporated Trades, (Aberdeen: Edmond & Spark, 1887).

- ↑ Different versions of the charter exist. The text in this article draws on: Richard W. K. Bain, James, and George Grub, Bishop Gavin Dunbar's Hospital. Memorandum Dealing with the History and Records from the Foundation of the Benefaction and List of Title Deeds and Other Writs Relating Thereto, (Aberdeen: Rosemount P., 1931). and A M Munro, Records of Old Aberdeen, Vol.2 (New Spalding Club, Aberdeen, 1899). The original 1531 charter by signed by James V and part of the Gavin Dunbar Hospital in the University of Aberdeen

- ↑ Last sentence of Psalm IX, v18 … The patient abiding of the poor shall not perish foe ever...

- ↑ William Orem, John Nichols, and Hector Boece, A Description of the Chanonry in Old Aberdeen : In the Years 1724 and 1725, Bibliotheca Topographica Britannica (London: Printed by and for J. Nichols ..., and sold by all the booksellers in Great-Britain and Ireland, 1782).

- ↑ It is most likely that the Thomas referred to was Thomas of Canterbury, not Thomas the Disciple. St Thomas of Canterbury has two Feast Days, 7 July and 29 December.

- ↑ See entries DE/JD/857 and EN/JD/642 from The Database of Dedications to Saints in Medieval Scotland, at, http://saints.shca.ed.ac.uk/index.cfm?fuseaction=home.search.

Further reading

- Ray McAleese, 'The Bede House and the Bedesmen in Old Aberdeen', Leopard, December/January (2011), 59-67.

- Ray McAleese, 'Old Aberdeen's Bedesmen - Poverty and Piety', History Scotland, 12 (2012), 26-29, 46-49.

- Ray McAleese, 'Gavin Dunbar: Nobleman, Statesman, Catholic Bishop and Philanthropist', Scottish Local History (2012), 14-21.

- Ray McAleese, 'Bishop Gavin Dunbar: Nobleman, Statesman, Catholic Bishop, Administrator and Philanthropist'. ed. by Walter R. H. Duncan, Friends of St Machar, Occasional Publications, Series 2, No. 7 (Aberdeen: Friends of St Machar, 2013), p. 40.