.jpg.webp) A Mono couple living near Northfork, California, ca. 1920 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| approximately 2,300 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| United States (California and Nevada) | |

| Languages | |

| Mono language "Nim", English | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional Tribal Religion, Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Northern Paiute, Shoshone, Bannock |

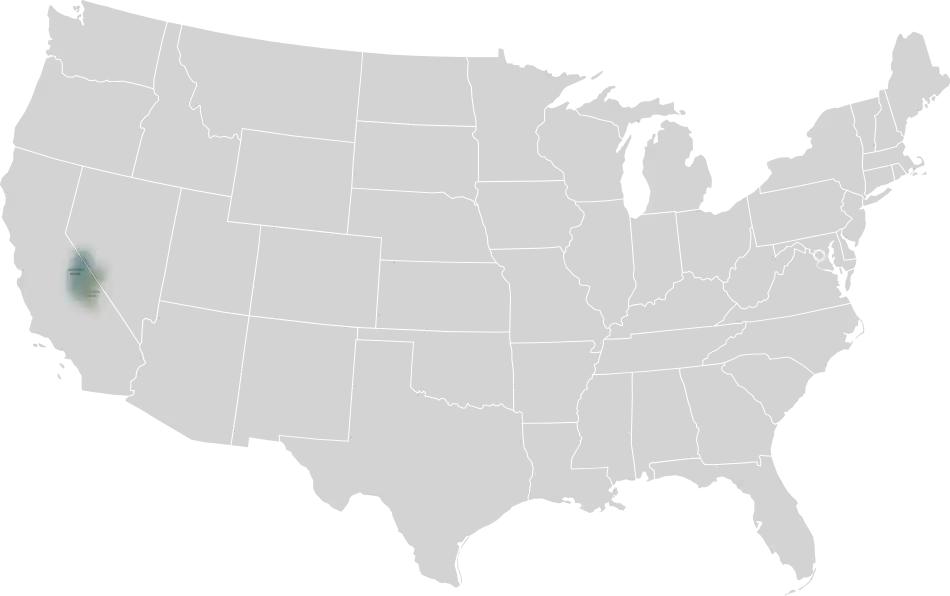

The Mono (/ˈmoʊnoʊ/ MOH-noh) are a Native American people who traditionally live in the central Sierra Nevada, the Eastern Sierra (generally south of Bridgeport), the Mono Basin, and adjacent areas of the Great Basin. They are often grouped under the historical label "Paiute" together with the Northern Paiute and Southern Paiute – but these three groups, although related within the Numic group of Uto-Aztecan languages, do not form a single, unique, unified group of Great Basin tribes.

Today, many of the tribal citizens and descendants of the Mono tribe inhabit the town of North Fork (thus the label "Northfork Mono") in Madera County. People of the Mono tribe are also spread across California in: the Owens River Valley; the San Joaquin Valley and foothills areas, especially Fresno County; and in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Tribal groups

The "Mono" lived on both sides of the Sierra Nevada and are divided into two regional tribal/dialect groups, roughly based on the Sierra crest:

- Eastern Mono Southernmost Northern Paiute live on the California-Nevada border on the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada in the Owens Valley (Mono: Payahǖǖnadǖ/Payahuunadu – "place/land of flowing water") along the Owens River (Wakopee) and south to Owens Lake (Pacheta). They are also known as the "Owens Valley Paiute"[1]

- Western Mono on the west side in the south-central foothills of the Sierra Nevada, including the "Northfork Mono," as labeled by E.W. Gifford, an ethnographer studying people in the vicinity of the San Joaquin River in the 1910s.[2]

Culture and geography

The current tribal name "Mono" is a Yokutsan loanword from the tribe's western neighbors, the Yokuts, who however hereby designated the Owens valley Paiutes as the southernmost Northern Paiute band living around "owens lake" / Mono Lake as monachie/monoache ("fly people") because fly larvae was their chief food staple and trading article[4] and not the "Mono". This "Kucadikadi Northern Paiute Band", whose autonym Kutsavidökadö/Kutzadika'a means "eaters of the brine fly pupae", are also known as Mono Lake Paiute or Owens Valley Paiute, a holdover from early anthropological literature, and are often confused with the non-Northern Paiute ethnic group of the Western mono "Mono".[5]

The "Eastern Mono" referred to themselves as Numa/Nuumu or Nüümü ("People") in their Mono language dialect and to their kin to the west as Panan witü / Pana witü ("western place" People); the "Western Mono" called themselves Nyyhmy/Nimi or Nim/Nium ("People"); a full blooded "Western Mono" person was called cawu h nyyhmy.[6]

Eastern Mono (Owens Valley Paiute)

The Owens Valley Paiute or Eastern Mono live on the California-Nevada border, they formerly ranged on the eastern side of the southern Sierra Nevada across the Owens Valley[7] along the Owens Rivers from Long Valley on the north to Owens Lake on the south, and from the crest of the Sierra Nevada on the west to the White and Inyo Mountains including the Fish Lake and Deep Springs Valleys on the east. They were predominantly sedentary and settled in fixed settlements along rivers or springs (or artificial canals). The more intensive arable farming by means of partly artificial irrigation enabled them to build up food reserves and thus, in contrast to the "Western Mono bands", to feed larger groups. The Sedentism is also reflected in their socio-political organization in different "districts" (each with communistic hunting and seed rights, political unity, and a number of villages), whose name mostly ended with "patü/witü", meaning "place" or "land"; each "district" was under the command of a headman or pohenaby.

Some "Owens Valley Northern Paiute" districts:

- Panatü (Black Rock Territory, south to Taboose Creek)

- Pitama Patü or Pitana Patü ("south place" = Bishop, California, extending from the volcanic tableland and Horton Creek in the Sierra to a line running out into Owens Valley from Waucodayavi, the largest peak south of Rawson Creek. Note that Waucodayavi does not have an English name, but is a peak of approximately 9,280 feet located almost due west of Keough Hot Springs.)

- Ütü’ütü witü or Anglicized to Utu Utu Gwaiti ("hot place" = Benton, California, from Keough Hot Springs south to Shannon Creek)

- Kwina Patii or Kwina Patü ("north place" = Round Valley, California)

- Tovowaha Matii, Tovowahamatü or Tobowahamatü ("natural mound place" = Big Pine, California, south to Big Pine Creek in the mountains, but with fishing and seed rights along Owens River nearly to Fish Springs)

- Tuniga witü, Tunuhu witü or Tinemaha/Tinnemaha ("around the foot of the mountain place" = Fish Springs, California)

- Ozanwitü ("salt place" from the saline lake = Deep Springs Valley, they called their valley Patosabaya and themselves Patosabaya nunemu.)

- Ka’o witü ("very deep valley" = Saline Valley, was Shoshoni with a few intermarried Paiute, but was accessible to Paiute for salt)

The tribal areas of the "Eastern Mono bands" bordered in the northwest on the areas of the hostile Southern Sierra Miwok with which it often came to conflicts, in the northeast several Northern Paiute bands migrated, in the southeast and south the Timbisha Shoshone and Western Shoshone bands, in the southwest the Tübatulabal (also: Kern River Indians) and in the west the "Western Mono bands".

The Owens Valley Paiute were also more aggressive and hostile towards neighboring Indian tribes and most recently they fought the Americans in the "Owens Valley Indian War" (1862 to 1863) with allied Shoshone, Kawaiisu and Tübatulabal The Owens Valley Paiutes are The Southernmost Northern Paiute Band.

Their self-designation is Numa, Numu, or Nüümü, meaning "People" or Nün‘wa Paya Hup Ca’a‘ Otuu’mu—"Coyote's children living in the water ditch".[8]

- Big Pine Paiute Tribe of the Owens Valley, Big Pine, California (also Timbisha)

- Fort Independence Indian Community of Paiute Indians, Independence, California

- Lone Pine Paiute-Shoshone Tribe, Lone Pine, California

- Bishop Paiute Tribe, Bishop, California (also Timbisha)

- Utu Utu Gwaitu Paiute Tribe of the Benton Paiute Reservation, Benton, California[9][10]

Western Mono

The "Western Mono bands" in the western southern Sierra Nevada foothills in the San Joaquin Valley (San Joaquin River was called typici h huu' – "important, great river"), Kings River and Kaweah River (in today's counties of Madera, Fresno and Tulare) lived mostly as typical semi-nomadic hunters and gatherers of fishing, hunting and gathering as well as agriculture. In the winter, several families descended into the river valleys and built together fixed settlements, most of which were used for several years. In summer the winter settlements were abandoned and the family groups migrated as hunters and gatherers to the more sheltered and cooler altitudes of the mountains. Therefore, these smaller groups are sometimes considered socio-politically not as bands but as local groups.

The tribal areas of the "Western Mono" bordered the (mostly) hostile Southern Sierra Miwok in the north, the "Eastern Mono" settled in the east, the Tübatulabal in the southeast and the Foothill Yokuts in the west.

Some "Western Mono bands" formed bilingual bands or units with "Foothill Yokuts" and partly took over their culture, so that today – except for one – each "Western Mono band" are only known under its "Yokuts" name. Even in the ethnological literature the original ethnic classification of the bands listed below is controversial; partly they are listed as "Foothill Yokuts bands" (who adopted the "Mono language" and culture through the immigration of the "Western Mono" and soon became bilingual) or as "Western Mono bands" (who would have adopted the language of the dominant "Foothill Yokuts"). In particular, the classification of the two Kings River bands – the Michahai / Michahay and Entimbich[11] – is difficult.

The Western Mono self-designation is Nyyhmy, Nimi, Nim or Nium, meaning "People" or cawu h nyyhmy.

By contact with the Europeans, the following bands (or local groups) could be distinguished (from north to south):[12]

- Northfork Mono or Nim / Nium: most isolated band of the "Western Mono", therefore not known under a "Yokuts" name. They lived generally along the northern shore of the San Joaquin River westward on both sides of its North Fork (and its tributaries) to Fine Gold Creek (shared territory with the Yokuts there); they established smaller settlements than the more southerly "Western Mono Bands".

- Wobonuch, Wobunuch, Woponunch or Wobonoch (plural: Wobenchasi): Lived in the foothills west of General Grant Grove (with the General Grant Tree) from the mouth of the North Fork Kings River into the Kings River upstream along several tributaries and including the Kings Canyon, along the Mill Flat Creek alone were two major settlements, their area includes today's Kings Canyon National Park.

- Entimbich, Endimbich, Endembich or Indimbich (Plural: Enatbicha): bilingual, probably originally a "Kings River Yokuts Band". Lived along the Kings River south and west of the Wobonuch, their main settlement was located in the area of today's Dunlap, California, further settlements were along Mill Creek, Rancheria Creek and White Deer Creek.

- Michahai or Michahay: bilingual, many mixed marriages with neighboring Waksachi, often regarded as a "Kings River Yokuts band". Lived along the Cottonwood Creek, a stream of the St. John's River, a tributary of the Kaweah River north of the municipality of Auckland, California.

- Waksachi (plural: Wakesdachi): bilingual, but basically "Mono (Nim)"-speaking, partly adopted the culture of the neighboring Yokuts. Their tribal area was in the Long Valley south of Mill Creek and along Eshom Creek, a tributary of the North Fork Kaweah River, other settlements were along Lime Kiln Creek (also known as Dry Creek), such as "Ash Springs" and "Badger Camp".

- Balwisha, Badwisha, Patwisha, Potwisha or Baluusha: bilingual, but basically "Mono (Nim)"-speaking, partly adopted the culture of the neighboring Yokuts. Lived along the Kaweah River tributaries (Marble, Middle, East and South Forks) westwards to Lake Kaweah. One of their westernmost villages was located on the left bank of the Kaweah River below the confluence of its North Forks and Middle Forks near the community of Three Rivers, California (near the confluence of the Middle, East and South Forks), eastwards they had settlements upstream along the Middle and East Forks as well as Salt Creeks. The Sequoia National Park is located in their territory today, their trading partners were the Wukchumni Yokuts.

If the Entimbich and Michahai are counted as "Kings River Yokuts" then beside the above-mentioned bands sometimes the following bands are listed:

- Posgisa, Poshgisha or Boshgesha: Lived on the southern shore of the San Joaquin River and south of the Northfork Mono along Big Sandy Creek to the headwaters of Little and Big Dry Creek; according to reports from neighboring Yokuts, there were two settlements near Auberry, California. Presumably identical with the group later called "Auberry Band of Western Mono", whose Mono/Nim-language name was ?unaħpaahtyħ ("that which is on the other side [of the San Joaquin River]") or Unapatɨ Nɨm ("About (the San Joaquin River) People").

- Holkoma: sometimes synonymously called "Towincheba" or "Kokoheba", but both seems only names for single Holkoma villages. Were living in settlements along a series of confluent streams – especially the Big Creek, Burr Creek and Sycamore Creek above the mouth of the Mill Creek into the Kings River.

- Big Sandy Rancheria of Mono Indians of California

- Cold Springs Rancheria of Mono Indians of California

- Northfork Rancheria of Mono Indians of California

- Table Mountain Rancheria of California[13]

- Tule River Indian Tribe of the Tule River Reservation[14]

The two clans of the North Fork Mono Tribe are represented by the golden eagle and the coyote. Mono traditions still in practice today include fishing, hunting, acorn gathering, cooking, healing, basket making, and games. The Honorable Ron Goode is the Tribal Chairman for the North Fork Mono Tribe, which is not a federally recognized tribe. The North Fork Rancheria of Mono Indians is the federally recognized tribe in North Fork and their Chairperson is Elaine Fink.

Ceremonies are performed at the Sierra Mono Museum[15] in North Fork, California, and an annual Indian Fair Days festival takes place on the first weekend of August every year to revive many traditions and rituals for tribal kin and tourists alike to enjoy.

Language

The Mono speak the Mono language, which together with the Northern Paiute language (a dialect continuum) forms the Western Numic branch of the Uto-Aztecan language family. Due to the geographical separation as well as the interaction with neighboring tribes and peoples (incorporation of loanwords and/or frequent Bilingualism) two very different dialects developed in the course of time which are difficult to understand for each other. The native language of the Mono people is referred to as "Nim."

Mun a hoo e boso. Mun a hoo e num. Mun a hoo to e hun noh pa teh can be translated as "Hello to my friends. Hello to the Mono people. Hello to the people from all over."[16]

Today, the "Mono language (Nim)" (including its two dialects) is critically endangered. Among about 1,300 "Western Mono (Mono or Monache) people", only about 20 active speakers and 100 half speakers speak "Western Mono" or the "Monachi/Monache" dialect (better known as: "Mono/Monache" or "Mono Lake Paiute"). Of the 1,000 "Owens Valley Paiute (Eastern Mono) people" there are only 30 active speakers of the "Eastern Mono" or "Owens Valley Northern Paiute" dialect left.

Population

Estimates for the pre-contact populations of most native groups in California have varied substantially. (See Population of Native California.) Alfred L. Kroeber (1925:883) suggested that the 1770 population of the Mono was 4,000. Sherburne F. Cook (1976:192) set the population of the Western Mono alone at about 1,800. Kroeber reported the population of the Mono in 1910 as 1,500.

Today, there are approximately 2,300 enrolled Mono people. The Cold Springs Mono have 275 tribal members.[17] The Northfork Mono's enrollment is 1,800, making them one of California's largest native tribes. The Big Sandy Mono have about 495 members. The Big Pine Band has 462 tribal members, but it is difficult to determine how many of these are Mono.[18]

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Survey of California and Other Indian Languages: Mono." University of California. 2009–2010 (retrieved 5 May 2010)

- ↑ California Indians and Their Reservations. Archived 2010-07-26 at the Wayback Machine SDSU Library and Information Access. (retrieved 24 July 2009)

- ↑ "Hunter-Gatherer Language Database". huntergatherer.la.utexas.edu.

- ↑ Sprague, Marguerite (2003). "Welcome to Bodie". Bodie's Gold. Reno, Nevada: University of Nevada Press. pp. 3, 205. ISBN 0-87417-628-X.

- ↑ Lamb gives the Mono language name for this Northern Paiute band as Kwicathyhka' ("larvae eaters").

- ↑ Sydney M. Lamb. 1957. Mono Grammar. University of California. Berkeley PhD dissertation. .pdf

- ↑ Liljeblad & Fowler 1986, p. 412.

- ↑ Pritzker 2000, p. 227.

- ↑ Liljeblad & Fowler 1986, p. 413.

- ↑ Pritzker 2000, pp. 229–230.

- ↑ the Entimbich were probably originally "Western Mono" and the Michahai / Michahay were probably "Foothill Yokuts" – but these bands lived in the border area of the two ethnic groups and developed a new identity as a bilingual entity through marriage, adoption of the respective foreign language and partly culture, for which it was irrelevant whether they were regarded as "Western Mono" or "Foothill Yokuts". It was only with the establishment of the reservations that traditional social ties were broken; today American English is the dominant language and the Entimbich identify themselves as "Foothill Yokuts" since the 1950s.

- ↑ "Robert F.G. Spier: Monache: Language, Territory, and Environment" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-28. Retrieved 2019-06-08.

- ↑ Pritzker, 159

- ↑ Pritzker, 137

- ↑ Sierra Mono Museum, accessed 7/9/2012

- ↑ The Western Mono People: Yesterday and Today. Archived 2008-04-20 at the Wayback Machine Northfork Rancheria of Mono Indians. (retrieved 24 July 2009)

- ↑ California Indians and Their Reservations. Archived 2010-01-10 at the Wayback Machine SDSU Library and Information Access. (retrieved 25 July 2009)

- ↑ History and Timeline. Archived 2008-04-22 at the Wayback Machine North Fork Rancheria of Mono Indians. (retrieved 25 July 2009)

References

- Cook, Sherburne F. 1976. The Conflict between the California Indian and White Civilization. University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Kroeber, A. L. 1925. Handbook of the Indians of California. Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin No. 78. Washington, DC.

- Liljeblad, Sven; Fowler, Catherine S. (1986). "Owens Valley Paiute". In d'Azevedo, Warren L. (ed.). Great Basin. Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 11. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 412–434. ISBN 978-0-160-04581-3.

- Pritzker, Barry M. (2000). A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

.jpg.webp)