| Symphonie fantastique | |

|---|---|

| Épisode de la vie d'un artiste… en cinq parties | |

| Symphony by Hector Berlioz | |

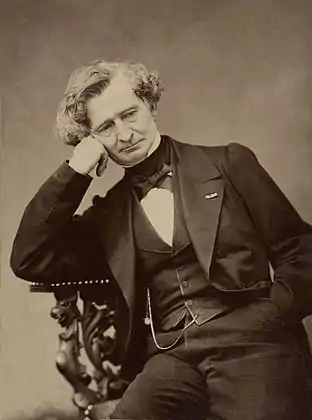

Hector Berlioz by Pierre Petit | |

| Opus | 14 |

| Period | Romantic music |

| Composed | 1830 |

| Dedication | Nicholas I of Russia |

| Duration | About 50 minutes |

| Movements | Five |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 5 December 1830 |

| Location | Paris |

| Conductor | François Habeneck |

Symphonie fantastique: Épisode de la vie d'un artiste… en cinq parties (English: Fantastical Symphony: Episode in the Life of an Artist… in Five Sections) Op. 14, is a program symphony written by the French composer Hector Berlioz in 1830. It is an important piece of the early Romantic period. The first performance was at the Paris Conservatoire on 5 December 1830. Franz Liszt made a piano transcription of the symphony in 1833 (S. 470).[1]

The American composer and conductor Leonard Bernstein described the symphony as the first musical expedition into psychedelia both because of its hallucinatory and dream-like nature, and because history suggests Berlioz composed at least a portion of it under the influence of opium. According to Bernstein, "Berlioz tells it like it is. You take a trip, you wind up screaming at your own funeral."[2][3]

Berlioz put a great deal of feeling into the piece, exploring the extremities of the emotional spectrum. He wanted people to understand his compositional intention, as the story he attached to each movement drove his musical choices. Berlioz said "For this reason I generally find it extremely painful to hear my works conducted by someone other than myself."[4]

In 1831 Berlioz wrote a lesser-known sequel to the work, Lélio, for actor, soloists, chorus, piano and orchestra.

Overview

Symphonie fantastique is a piece of program music that tells the story of a gifted artist who, in the depths of hopelessness and despair because of his unrequited love for a woman, has poisoned himself with opium. The piece tells the story of the artist’s drug-fueled hallucinations, beginning with a ball and a scene in a field and ending with a march to the scaffold and a satanic dream. The artist’s passion is represented by an elusive theme called the idée fixe (i.e. the object of fixation — a contemporary medical term also found in literary works of the period).[5][6]

Berlioz provided his own preface and program notes for each movement of the work. They exist in two principal versions: one from 1845 in the first edition of the work and the second from 1855.[7] Because of these changes, it can be seen how Berlioz downplayed the programmatic aspect of the piece later in life.

In the 1845 first edition, he writes:[7]

The composer's intention has been to develop various episodes in the life of an artist, in so far as they lend themselves to musical treatment. As the work cannot rely on the assistance of speech, the plan of the instrumental drama needs to be set out in advance. The following programme must therefore be considered as the spoken text of an opera, which serves to introduce musical movements and to motivate their character and expression.

%252C_by_George_Clint.jpg.webp)

In 1855, Berlioz writes:[7]

The following programme should be distributed to the audience every time the Symphonie fantastique is performed dramatically and thus followed by the monodrama of Lélio which concludes and completes the episode in the life of an artist. In this case the invisible orchestra is placed on the stage of a theatre behind the lowered curtain. If the symphony is performed on its own as a concert piece this arrangement is no longer necessary: one may even dispense with distributing the programme and keep only the title of the five movements. The author hopes that the symphony provides on its own sufficient musical interest independently of any dramatic intention.

Inspiration

After attending a performance of William Shakespeare's Hamlet on 11 September 1827, Berlioz fell in love with Irish actress Harriet Smithson, who played the role of Ophelia. He sent her numerous love letters, all of which were unanswered. When she left Paris in 1829, they had still not met.[8] Berlioz wrote Symphonie fantastique as a way to express his obsession. Smithson did not attend the premiere in 1830, but she heard the work in 1832 and realized the piece was about her. Berlioz began to court Smithson and later manipulated her into marriage by swallowing a lethal dose of opium in front of her. Hysterical, she accepted the proposal, upon which Berlioz produced a vial of antidote from his other pocket. The two were married in 1833 and eventually separated.[6]

Instrumentation

The score calls for an orchestra of about 90 musicians:

|

|

|

Berlioz originally wrote for one serpent and one ophicleide, but quickly switched to two ophicleides after the serpent proved to be difficult to use.

Each of the 5 movements had a different instrumentation. Berlioz was one of the first to employ such a huge orchestra, and his successors continue this trend.

Berlioz also brings unique instrumentation and playing techniques into the piece. The piece was one of the earliest symphonies where the English horn played a large role. He includes an imitative duet between an off-stage oboe and the English horn. Berlioz also utilizes col legno bowing for the strings, a technique used very infrequently by major composers during his career.

Movements

The symphony has five movements, instead of four as was conventional for symphonies of the time:

Each movement depicts an episode in the protagonist's life that is described by Berlioz in the program notes to the 1845 score.[7] These program notes are quoted in each section below.

I. "Rêveries – Passions" (Daydreams – Passions)

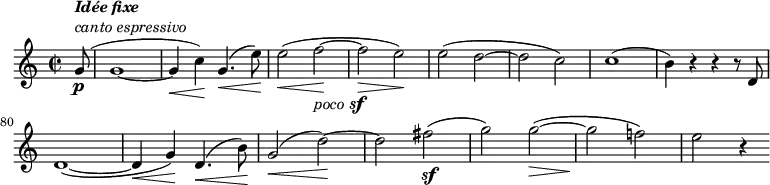

The author imagines that a young musician, afflicted by the sickness of spirit which a famous writer[lower-alpha 1] has called the vagueness [or confusion] of passions (vague des passions),[lower-alpha 2] sees for the first time a woman who unites all the charms of the ideal person his imagination was dreaming of, and falls desperately in love with her. By a strange anomaly, the beloved image never presents itself to the artist's mind without being associated with a musical idea, in which he recognizes a certain quality of passion, but endowed with the nobility and shyness which he credits to the object of his love.

This melodic image and its model keep haunting him ceaselessly like a double idée fixe. This explains the constant recurrence in all the movements of the symphony of the melody which launches the first allegro. The transitions from this state of dreamy melancholy, interrupted by occasional upsurges of aimless joy, to delirious passion, with its outbursts of fury and jealousy, its returns of tenderness, its tears, its religious consolations – all this forms the subject of the first movement.

- ↑ François-René de Chateaubriand

- ↑ For the meaning of 'le vague', see vague at Wiktionary.

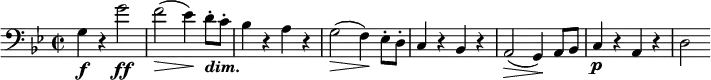

The first movement is radical in its harmonic outline, building a vast arch back to the home key; while similar to the sonata form of the classical period, Parisian critics regarded this as unconventional. It is here that the listener is introduced to the theme of the artist's beloved, or the idée fixe. The idée fixe begins:

Throughout the movement there is a simplicity in the way melodies and themes are presented, which Robert Schumann likened to Beethoven's epigrams' ideas that could be extended had the composer chosen to. In part, it is because Berlioz rejected writing the more symmetrical melodies then in academic fashion, and instead looked for melodies that were "so intense in every note as to defy normal harmonization", as Schumann put it. The theme itself was taken from Berlioz's scène lyrique "Herminie", composed in 1828.[9]

II. "Un bal" (A ball)

The artist finds himself in the most diverse situations in life, in the tumult of a festive party, in the peaceful contemplation of the beautiful sights of nature, yet everywhere, whether in town or in the countryside, the beloved image keeps haunting him and throws his spirit into confusion.

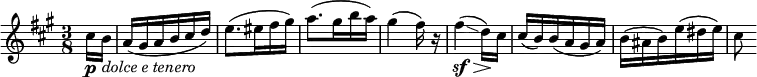

The second movement is a waltz in 3

8. It begins with a mysterious introduction that creates an atmosphere of impending excitement, followed by a passage dominated by two harps; then the flowing waltz theme appears, derived from the idée fixe at first,[10] then transforming it. More formal statements of the idée fixe twice interrupt the waltz.

The movement is the only one to feature the two harps, providing the glamour and sensual richness of the ball, and may also symbolize the object of the young man's affection. Berlioz wrote extensively in his memoirs of his trials and tribulations in having this symphony performed, due to a lack of capable harpists and harps, especially in Germany.

Another feature of this movement is that Berlioz added a part for solo cornet to his autograph score, although it was not included in the score published in his lifetime. The work has most often been played and recorded without the solo cornet part.[11] However, conductors Jean Martinon, Colin Davis, Otto Klemperer, Gustavo Dudamel, John Eliot Gardiner, Charles Mackerras, Jos van Immerseel and Leonard Slatkin have employed this part for cornet in performances of the symphony.

III. "Scène aux champs" (Scene in the country)

One evening in the countryside he hears two shepherds in the distance dialoguing with their ranz des vaches; this pastoral duet, the setting, the gentle rustling of the trees in the wind, some causes for hope that he has recently conceived, all conspire to restore to his heart an unaccustomed feeling of calm and to give to his thoughts a happier colouring. He broods on his loneliness, and hopes that soon he will no longer be on his own... But what if she betrayed him!... This mingled hope and fear, these ideas of happiness, disturbed by dark premonitions, form the subject of the adagio. At the end one of the shepherds resumes his ranz des vaches; the other one no longer answers. Distant sound of thunder... solitude... silence.

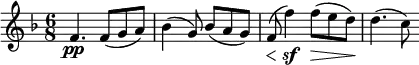

The third movement is a slow movement, marked Adagio, in 6

8. The two shepherds mentioned in the program notes are depicted by a cor anglais (English horn) and an offstage oboe tossing an evocative melody back and forth. After the cor anglais–oboe conversation, the principal theme of the movement appears on solo flute and violins. It begins with:

Berlioz salvaged this theme from his abandoned Messe solennelle.[9] The idée fixe returns in the middle of the movement, played by oboe and flute.[12] The sound of distant thunder at the end of the movement is a striking passage for four timpani.[9]

IV. "Marche au supplice" (March to the scaffold)

Convinced that his love is spurned, the artist poisons himself with opium. The dose of narcotic, while too weak to cause his death, plunges him into a heavy sleep accompanied by the strangest of visions. He dreams that he has killed his beloved, that he is condemned, led to the scaffold and is witnessing his own execution. The procession advances to the sound of a march that is sometimes sombre and wild, and sometimes brilliant and solemn, in which a dull sound of heavy footsteps follows without transition the loudest outbursts. At the end of the march, the first four bars of the idée fixe reappear like a final thought of love interrupted by the fatal blow.

Berlioz claimed to have written the fourth movement in a single night, reconstructing music from an unfinished project, the opera Les francs-juges.[9] The movement begins with timpani sextuplets in thirds, for which he directs: "The first quaver of each half-bar is to be played with two drumsticks, and the other five with the right hand drumsticks". The movement proceeds as a march filled with blaring horns and rushing passages, and scurrying figures that later show up in the last movement.

Before the musical depiction of his execution, there is a brief, nostalgic recollection of the idée fixe in a solo clarinet part, as though representing the last conscious thought of the soon-to-be-executed man.[2]

V. "Songe d'une nuit du sabbat" (Dream of a Night of the Sabbath)

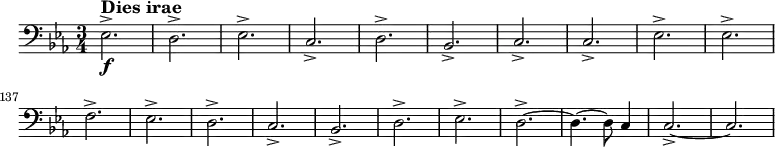

He sees himself at a witches' sabbath, in the midst of a hideous gathering of shades, sorcerers and monsters of every kind who have come together for his funeral. Strange sounds, groans, outbursts of laughter; distant shouts which seem to be answered by more shouts. The beloved melody appears once more, but has now lost its noble and shy character; it is now no more than a vulgar dance tune, trivial and grotesque: it is she who is coming to the sabbath ... Roar of delight at her arrival ... She joins the diabolical orgy ... The funeral knell tolls, burlesque parody of the Dies irae, the dance of the witches. The dance of the witches combined with the Dies irae.

This movement can be divided into sections according to tempo changes:

- The introduction is Largo, in common time, creating an ominous quality through the copious use of diminished seventh chords [13] dynamic variations and instrumental effects, particularly in the strings (tremolos, pizzicato, sforzando).

- At bar 21, the tempo changes to Allegro and the metre to 6

8. The return of the idée fixe as a "vulgar dance tune" is depicted by the B♭ clarinet. This is interrupted by an Allegro Assai section in cut time at bar 29. - The idée fixe then returns as a prominent E♭ clarinet solo at bar 40, in 6

8 and Allegro. The E♭ clarinet contributes a brighter timbre than the B♭ clarinet. - At bar 80, there is one bar of alla breve, with descending crotchets in unison through the entire orchestra. Again in 6

8, this section sees the introduction of the bells and fragments of the "witches' round dance". - The "Dies irae" begins at bar 127, the motif derived from the 13th-century Latin sequence. It is initially stated in unison between the unusual combination of four bassoons and two ophicleides. The key, C minor, allows the bassoons to render the theme at the bottom of their range.

- At bar 222, the "witches' round dance" motif is repeatedly stated in the strings, to be interrupted by three syncopated notes in the brass. This leads into the Ronde du Sabbat (Sabbath Round) at bar 241, where the motif is finally expressed in full.

- The Dies irae et Ronde du Sabbat Ensemble section is at bar 414.

There are a host of effects, including trilling in the woodwinds and col legno in the strings. The climactic finale combines the somber Dies Irae melody, now in A minor, with the fugue of the Ronde du Sabbat, building to a modulation into E♭ major, then chromatically into C major, ending on a C chord.

References

- ↑ Howard, Leslie (1991). "History of Liszt's Transcription of Symphonie fantastique". Hyperion Records.

- 1 2 "Leonard Bernstein – Young People's Concerts". leonardbernstein.com. Archived from the original on 2014-12-05. Retrieved 2014-11-30.

- ↑ Bernstein, Leonard (2006). Young People's Concerts. Cleckheaton, West Yorkshire: Amadeus Press. ISBN 978-1-5746-7102-5.

- ↑ O'Neal, Melinda (2019). Experiencing Berlioz: A Listener's Companion. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-8108-8606-3. OCLC 1001413971.

- ↑ Brittan, Francesca (2006). "Berlioz and the Pathological Fantastic: Melancholy, Monomania, and Romantic Autobiography". 19th-Century Music. 29 (3): 211–239. doi:10.1525/ncm.2006.29.3.211.

- 1 2 "Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique: Keeping Score | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2023-04-21.

- 1 2 3 4 Translation of Berlioz's program notes to the Symphonie fantastique

- ↑ Taruskin, Richard (2019) [2013]. The Oxford History of Western Music (2 ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 449.

- 1 2 3 4 Steinberg, Michael. "The Symphony: A Listener's Guide". pp. 61–66. Oxford University Press, 1995.

- ↑ "Hector Berlioz – Discussion on Symphonie fantastique". ugcs.caltech.edu. Archived from the original on 2015-11-26.

- ↑ The Hector Berlioz Website: Berlioz Music Scores. Retrieved 26 July 2014

- ↑ Bernstein, Leonard. "Berlioz Takes a Trip": Commentary on Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique

- ↑ Hovland, E. (2019, p20) “Who’s afraid of Berlioz?” Studia Musicologica Norvegica. Vol 45, No. 1, pp9-30.

Sources

- Holoman, D. Kern, Berlioz (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1989). ISBN 0-674-06778-9.

- Oxford Companion to Music, Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-19-866212-2.

- Wright, Craig, "The Essential Listening to Music" (Schirmer, Cengage Learning 2013). ISBN 978-1-111-34202-9.

External links

- Symphonie fantastique on the Hector Berlioz Website, with links to Scorch full score and program note written by the composer.

- Symphonie fantastique: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Keeping Score: Berlioz Symphonie fantastique, multimedia website with interactive score produced by the San Francisco Symphony

- European Archive. A copyright-free LP recording of the Symphonie fantastique by Willem van Otterloo (conductor) and the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra at the European Archive

- Beyond the Score. A concert-hall dramatized documentary and performance with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

- Symphonie fantastique at the Internet Archive, performed by the Cleveland Orchestra, Artur Rodzinski conducting

- Complete performance of the symphony by the London Symphony Orchestra accompanied by visual illustrations of the symphony's programme