Benito Juárez | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp)       Aerial view at night, View of the Estadio Azul, Insurgentes Sur avenue, View of the Polyforum Cultural Siqueiros, Sunken Park "Luis G. Urbina", church of San Lorenzo Xochimanca and World Trade Center | |

Seal | |

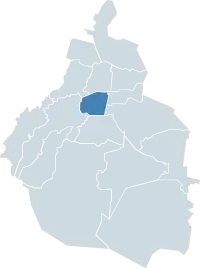

Benito Juárez within Mexico City | |

| Country | |

| Federal entity | |

| Established | 1941 |

| Named for | Benito Juárez |

| Seat | Municipio Libre esq. División del Norte Col. Santa Cruz Atoyac, Benito Juárez C03310 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Santiago Taboada (PAN) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 26.62 km2 (10.28 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 2,242 m (7,356 ft) |

| Population (2020)[3] | |

| • Total | 434,153 |

| • Density | 16,000/km2 (42,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central Standard Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (Central Daylight Time) |

| Postal codes | 03000–03949 |

| Area code | 55 |

| HDI (2010) | |

| Website | alcaldiabenitojuarez.gob.mx |

Benito Juárez (pronounced [beˈnito ˈxwaɾes] ⓘ), is a borough (demarcación territorial) in Mexico City. It is a largely residential area, located to the south of historic center of Mexico City, although there are pressures for areas to convert to commercial use. It was named after Benito Juárez, president in the 19th century.

The borough has the highest socioeconomic index in the country as it is primarily populated by the middle and upper middle classes. The borough is home to a number of landmarks such as the World Trade Center Mexico City, the Estadio Azul, the Plaza México and the Polyforum Cultural Siqueiros.

The borough

The borough is in the north center of the Mexico City, just south of the oldest section of the city. It borders the boroughs of Miguel Hidalgo, Cuauhtémoc, Coyoacán, Iztapalapa, Iztacalco and Álvaro Obregón. The borders are formed by two rivers, the La Piedad and the Churubusco, as well as the following streets: Presidente Adolfo López Mateos (Anillo Periférico), 11 de Abril, Avenida Revolución, Puente de la Morena, Viaducto Miguel Alemán, Calzada de Tlalpan, Santa Anita, Atzayacatl, Plutarco Elías Calles and Barranca del Muerto.[5][6] Many of the names of the rivers, streets and neighborhoods have their origin in the pre Hispanic period.[6]

It has a territory of 26.63 km2 (2,661.5 hectares), which is 1.8% of Mexico City, with an average altitude of 2,242 metres. It consists of 56 neighborhoods called "colonias" and three major apartment complexes (unidades habitacionales) which cover 2,210 city blocks and through which some of the most important city thoroughfares pass.[5][7][8] The borough is nearly entirely residential with a socioeconomic level of middle class to upper middle class.[9]

The borough is located in the southwest part of the Valley of Mexico.[5] The land is flat with little variation and a portion of it is former lakebed of Lake Texcoco.[8][10] The ground is highly elastic clay which extends down for about fifteen meters. The climate is temperate with an average annual temperature of 17C.[8]

Most of the neighborhoods of the borough have a socioeconomic level of middle class to upper middle class.[9] Forty two percent of the land is zoned for mixed use (residential/commercial), thirty nine percent residential, thirteen percent for storage and warehouses, four percent for open space and two percent industrial.[7][11] Almost all housing and other construction consists of cement, cinderblock or brick, including both walls and roofs.[10] The total number of housing units is 115,975, with 99.9% privately owned. The average number of people per household is 3.1. About 94% of housing is constructed in accordance to building codes. Housing units mostly consist of individual houses (27%), apartments in complexes (62%) and a housing arrangement called a "vecindad" (5%). Over 99% of residential units have running water, 99.5% have sewerage and 100% have electricity.[11] The most important colonias are Nápoles, Del Valle, Narvarte, Mixcoac, Portales, Ciudad de los Deportes, San José Insurgentes, San Pedro de los Pinos, Xoco, Insurgentes Mixcoac, General Anaya, Noche Buena and Nativitas.[10]

Landmarks

The World Trade Center is located in Colonia Nápoles.[12] It was a development project conceived in 1947, in an area called Parque de la Lama. However, political opposition stalled the project until the 1960s. At this time, in preparation for the 1968 Olympics, the project moved forward with a total eleven spaces centered on the Hotel de México building. This complex includes the Polyforum, a commercial center, a Public Art school, a handcrafts market, a dinner theatre, garden areas, parking garage and a public transportation hub. Most of the complex would not be completed until the 1980s and the World Trade Center tower was inaugurated in 1994. Today the complex extends over covers an area of 81,000m2.[13]

Next door to each other are the Estadio Azul (lit. Blue Stadium) and the Plaza México bullring, also on the west side of the borough. The two were constructed as part of a large project called the Ciudad de los Deportes (Sports City). This project was conceived in the late 1930s to cover what was formerly the San José Hacienda. The complex was to include swimming pools, a baseball field, an indoor jai alai court along with several outdoor ones, boxing and lucha libre rings, theatres, forty tennis courts, restaurants and parking for over two thousand cars. However, the developer went bankrupt with only the bullring near completion. This bullring was begun in 1944 and opened in 1946. It was built to replace the El Toreo ring in the La Roma neighborhood, which dated from 1907. The new facility was built with the express purpose of being the largest in the world. The bullring covers a surface of 1452m2 with a 43-meter diameter. The stands extend up for 35.9 meters and the sand area is twenty meters below street level. There is seating for between 45,000 and 48,000 people.[14]

Both the bullring and the Estadio Azul stadium have playing fields which are about twenty meters below street level. This is because both were built over the firing pits for former brick making operations of the hacienda. The stadium was inaugurated in 1947 and has been the home of the Cruz Azul professional soccer team since 1996.[14][15] The Ciudad de Deportes was planned so that cars can easily enter and exit the area, but over time, housing and other construction has crowded the area around these two landmarks. Since the 1940s, the complex has been owned and operated by the Cosío family.[14]

The Polyforum Cultural Siqueiros was built to be a multipurpose forum to host cultural, political and social events. It is divided into several areas include a 500-seat theater, galleries, offices and the main forum space. The building is also a museum hosting twelve panels on the outside walls and 2,400 meters of interior painted with a mural called "The March of Humanity" by David Siqueiros. Today it remains a private institution supported by the activities it hosts and donations made to the Siqueiros Foundation.[16] The interior mural work was originally planned for a hotel in Cuernavaca with the theme of the history of humanity. However, the concept grew to more than the hotel could host, and it was later thought to put the work in its own building in Mexico City. This eventually became the Polyforum Siqueiros with the aim of constructing the largest mural in the world, which it remains to this day.[17]

The borough is home to a number of houses of notable persons, many of which were part of the intellectual and political life of Mexico. As of 1945, many of these homes, up to those constructed in the late 19th and early 20th century have been declared under a state of conservation.[18] One example of this is the house in which lived Valentín Gómez Farías in what was the village of San Juan Mixcoac. It was constructed in the 17th century and still remains.[19]

The borough has a number of public sports facilities and cultural institutions. Sports facilities include the Olympic complex of the Francisco Márquez Pool and Juan de la Barrera Gymnasium, Benito Juárez Sports Complex, Joaquín Capilla Sports Complex, Tirso Hernández Sports Complex and the Gumersindo Romero Sports Complex.[20] The borough has thirteen "casas de cultura" or cultural centers to promote culture through artistic, social, handcrafts events as well as through the staging of plays. The borough also has an established for Desarrollo Social (Social Development), and audio library and a Casa Museo museum.[18]

History

Name and symbol

The borough was created in 1970 and named after former Mexican president Benito Juárez.[21] The current logo for the borough was adopted in 2001, which is a stylized depiction of the head of President Benito Juárez. The prior logo was a glyph of a serpent which is symbolic of Mixcoac.[22]

Archeology

The main archeological finds of the area are Aztec/Mexica and include those in Mixcoac, Actipan, Tlacoquemécatl, Xoco, Portales, Ticomán, La Piedad, Ahuehuatlan, Barrio de San Juan, San Pedro de los Pinos Acachinaco (Nativitas) and one at the Metro Zapata station. The pyramid base as San Pedro de los Pinos is located near Mixcoac. It is the only one of its kind left in the borough, discovered in 1916 by Francisco Fernández del Castillo. It was a Mexica temple dedicated to the god Mixcoatl. The site also contains two temazcals as well as two Teotihuacan style sculpted heads. Artifacts have been found in other areas as well such as Xoco and Santa Cruz which include ceramics, stone knives and figurines. In the former village of Atoyac, a pre-Hispanic idol was found during the colonial era and destroyed by the Spanish. The Spanish village was built over a Mesoamerican one, which was dedicated to Tlahuac. The church of Santa Cruz Atoyac was built over the temple.[6]

Colonial period

Except for small villages on the east and west side, most of the territory of the modern borough was covered by the waters of Lake Texcoco during the pre-Hispanic period.[10] Crossing part of the east side was a causeway that linked Tenochtitlan to Iztapalapa and Tlalpan.[10][23] After the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, the first colonial era constructions in the area were evangelical churches built by the Franciscans such as the Church of Santa Cruz in Atoyac in 1564 and the Santo Domingo de Guzmán Church in Mixcoac in 1595.[10][19] In the early colonial period, most of the area came under the jurisdiction of Hernán Cortés as part of his Coyoacán properties.[24] As Lake Texcoco dried, the area became dotted with villages under the hacienda system and had some important roads leading south from Mexico City. The old causeway became the Calzada de Tlalpan and would eventually become the first to be paved.[23] In the Mixcoac area, villages dotted an important colonial era road that connected the main village of Mixcoac with Tacubaya.[10] Other important roads included that with linked San Ángel to Tacubaya, called the Atlacuihuayan, today Avenida Revolución, and the road that linked village of La Piedad with Mexico City over which bricks and pulque was transported.[23]

The Cortés family would lose their Coyoacán lands by the early 17th century but as the lake dried, the area remained a rural zone just south of Mexico City. This city would remain within its conquest-era boundaries for all of the colonial period into the 19th century, with the Spanish living in the city and the indigenous living in the rural areas outside. However, these indigenous lost control over lands they held previously. Whatever lands they still held communally would be eventually taken over by growing Spanish-held haciendas. This area not only provided agricultural goods to Mexico City but was also important for brick making. These operations would remain important through the colonial era into the mid 19th century.[24] In the 18th century, the territory of the modern borough included the villages of Santo Domingo, Mixcoac, La Piedad, Santa Cruz Atoyac, Actipan, San Juan Maninaltongo, Santa María Nonoalco and Xoco along with the la Candelaria, Santo Tomás Tecoyotitla and Atepuxco neighborhoods and the ranches and haciendas of Los Portales, San Borja, Nalvarte (Narvarte), San Simón, Santa Cruz, La Piedad and San Andrés de las Ladrilleras.[24]

19th century

At the beginning of the 19th century and after the Mexican War of Independence, the Federal District of Mexico was created by the 1824 Constitution. This district would border but not include what is now the Benito Juárez borough, which was still rural farmland and pasture. For much of the colonial period, one of the major industries of the area was brick making, mostly for nearby Mexico City. However, by 1855 only ten small operations were left.

During the 19th century, much of the farmland disappeared and many former farm workers became factory workers, especially in textiles. Instead it was part of the Tacubaya prefecture divided into five municipalities, Tacubaya, Tacuba, Santa Fe, Cuajimalpa and Mixcoac. In 1826, much of Coyoacán, along with what are now Tlalpan, Xochimilco and Mexicalzingo became part of the State of Mexico, splitting off much of the Benito Juárez territory from Hernán Cortés’ old Coyoacan lands. For most of the 19th century, most of the borough was part of the then municipality of Tacubaya, with Mixcoac and the municipal seat. Its economy was based on meeting Mexico City's needs for grains, flowers, pulque, textiles and other products although some were exported.[24]

The wars of the 19th century affected the area. In 1847, U.S. troops fought their way through the territory on their way to conquering the center of Mexico City. These troops enacted a diversionary tactic at the Portales Hacienda, which allowed them to circle around and gain access to Chapultepec a day later. After this war, the Federal District was expanded to include this area along with areas farther to the south, but it was still considered outside the city proper. During the Reform War the San Pedro de los Pinos and Mixcoac areas were Liberal strongholds under General Santos Degollado.[24]

By the early 20th century, old villages such as Nonoalco, Xoco, Catipan, San Simón Ticumac, Tlacoquemécatl and Nativitas had been integrated into the ranches and haciendas of the area, which still dominated the area. Some larger villages such as Mixcoac and La Piedad remained. La Piedad was connected to Mexico City via an avenue called La Quinta Monterde, today called Calzada Ermita. It was also known for its two cemeteries, one where common people were buried and the other, the Panteón Francés, for those with money. The first attempt to integrate the area with Mexico City proper came in 1867, but the locals especially of the village of La Piedad resisted.[25] However, these villages were increasingly connected to the main urban center. In the 1870s, trolleys pulled by mules were operating in the area, with the first trolley concession operated by Jorge Luis Hemmerken that connected the Zocalo with San Angel and Mixcoac with Tacubaya.[26]

Further integration of the area into Mexico City proper came in 1899 when prefectures such as Tacubaya, Mixcoac, and General Anaya became part of the city's direct jurisdiction.[19][25] The Federal District was reorganized into thirteen municipalities in 1903, with the Tacubaya area (which then accounted for much of what is now Benito Juárez) divided into the municipalities of Mixcoac, Santa Fe, Cuajimalpa and the village of Tacubaya.[25]

Mexican Revolution to the present

During the Mexican Revolution, the Zapatistas took control of the south of the Federal District, including parts of Benito Juárez like Mixcoac.[25]

Residential development of the Benito Juárez area began during and after the Mexican Revolution. Between 1909 and 1910, the streets began to be paved and numbers put on the houses. Most of the new streets in the borough are named after famous men and women from the Porfirio Díaz era. These include doctors such as Nicolás San Juan, lawyers such as Artemio de Valle Arizpe and Jose Linares, and engineers such as Gabriel Mancera. However, most of these people did not live in the area.[25] In the 1920s, there was haphazard and unregulated subdivision development over old haciendas with the initial purpose of building country homes. This is the origin of modern "colonia" neighborhoods such as Del Valle, California, Berlín, Carrera Lardizábal, La Laguna and El Zacate. However, a number of villages still remained such as Mixcoac, San Pedro de los Pinos, Actipan and Tacubaya. Later in the decade, development would be more orderly and created subdivisions in Mixcoac, Tacubaya, San Pedro de los Pinos, Actipan, Navarrete and other areas.[10][27] In addition, a number of colonias were created on the east side to meet the demand for middle class housing, resulting in Moderna, Portales, Santa Cruz, Postal, Álamos, Niños Héroes and Independencia.[27] Trolley cars were introduced to facilitate transportation. This construction, along with the construction of major thoroughfares would result in the development of the borough without any ecological reserve space or major parks. Its location next to the historical extension of Mexico City proper would also mean that it would gain all city services earlier than the rest of the Federal District.[10] This development for upper and middle classes, along with the installation of good infrastructure such as roads, schools and hospitals would allow the borough to develop with no major areas for the poor.[28]

In 1928, the Federal District was reorganized into a Central Department and thirteen boroughs. Most of the Benito Juárez area was part of the Central Department, with a small section belonging to the municipality of General Anaya.[19][27] Another reorganization in 1941, split the Central Department into four entities, Benito Juárez along with Cuauhtémoc, Venustiano Carranza and Miguel Hidalgo. The new Benito Juárez borough also included part of the General Anaya municipality, which was split between it and Coyoacán.[19][27] The final borders of the borough were established on December 29, 1970, when the former circumscription of Mexico City was abolished and the Benito Juárez borough formally incorporated.[10][29]

For most of the area's history, population growth was very slow. As late as the 1850s, the municipality of Mixcoac only had 1,500 people.[30] Urbanization began in the first half of the 20th century, but major population expansion did not occur until the 1950s when apartment buildings began to replace houses. This construction was so rapid that by 1960, the borough was considered to be completely urbanized. This was part of a process of the sudden growth of Mexico City in general, which expanded over Benito Juárez and south into Coyoacán and other southern boroughs. Benito Juárez became part of the city proper, but mostly residential, inhabited by the middle class and higher. However, the street patterns of a number of former villages can still be discerned in some areas, with many of these areas still containing older, rustic homes. This is particularly true in Mixcoac, San Juan, San Simón Ticumac, San Pedro de los Pinos, Actipan and Nonoalco.[27]

The strongest population growth occurred between 1950 and 1960. In 1969, Plaza Universidad shopping mall opened, Mexico City's first shopping center anchored by a department store.[31] Since 1970, the population has continued to grow but slower, today ranking between fourth and fifth place in population in Mexico City.[30] The Mixcoac and Churubusco Rivers were encased in cement tubes where they cross the borough. This eliminated the last of the area's surface water.[23]

The population decline in the borough since the 1980s has negatively affected the economy and tax base of the area with little new construction from then until the 2000s.[28][32] There is strong economic pressure to convert residential structures and areas into commercial units mostly due to the borough centralized location and accessibility by road. This saturation has led to zoning violations and traffic congestion.[10] Since 2000, the borough has worked to attract young families such as those who made it grow in the 1950s and 1960s. However, these are now two income families who need cars in order to commute to places like the north of the city, Santa Fe and Vallejo.[28] From 2001 to 2007, the borough constructed 31,569 new residences; however, it did not result in an increase in population. It lost 5,000 in the same time period.[32] The construction boom of the 2000s, resulted in a number of serious building code violations with 51% of the 1,816 buildings with 30,873 apartments judged deficient. Most of these violations are related to the number of parking spaces available as well as the amount of free space among apartments. The large number of new apartments built in that time period has put strain on city services.[33] The building of massive apartment complexes has caused complaints in the borough as neighbors of these developments claim that crime rates go up. As of 2002, buildings of more than six stories are limited to certain neighborhoods.[34]

The development of housing for the middle class and above from the 1920s on has meant that Benito Juárez the gap between rich and poor is less here than in other boroughs such as Miguel Hidalgo. Overall, the borough has the highest socioeconomic indicators in the country, according to the United Nations Development Programme. Its indicators are equivalent to those in Germany, Spain, Italy and New Zealand. The borough ranks highest in personal income, health indicators and education.[35]

However, these socioeconomic indicators have not protected the borough from crime problems, especially in the past few decades. There has been a rise in crime rates, especially robbery of banks and cars.[36][37] The number of crimes has increased and the borough is now ranked fourth in overall crime rates, moving up from fifth place in 2008.[38] Most reported crime consists of robbery at 52.8% followed by assaults at 15.3%.[7] One of the most dangerous areas is along Calzada de Tlalpan because of the heavy through traffic allowing perpetrators to disappear into the crowd.[37] The colonia with the highest crime rate is Narvarte. Another problematic area is Colonia Álamos because of the high number of people passing through.[38] Upper class Del Valle has begun to have problems with robberies and transients.[9][36] The borough states that one of the main reasons for the high crime rates is that delinquents from other parts of the city come to the area looking for victims.[39] Most of the crime takes place in eleven colonias including Insurgentes Mixcoac, San Pedro de los Pinos, Nápoles, la Unidad Miguel Alemán, Del Valle Norte, Narvarte Poniente, Niños Héroes, Nativitas, Portales Norte, Del Lago and Álamos.[36]

Demographics

The borough is currently one of the most densely populated in Mexico City with 16,260 inhabitants per km2, 1.3 times the density of Mexico City as a whole. During work days, another million and a half people come into the borough to work or shop.[10][30] Most of the population of the borough occurred in the mid 20th century and since then there has been a slight negative growth rate starting at −2.9% in the 1980s to -.03% in 2005, although population increased again from 2010 to 2020.[7] The most populous neighborhoods include Narvarte Oriente, Narvarte Poniente, Del Valle Centro, Portales Norte, Del Valle Norte, El Valle del Sur, Portales Sur and Álamos.[10]

The population of the borough is slightly older than the Mexico City average, with the highest overall standard of living. The average age in Benito Juárez is 33 years compared to the city average of 27.[10] Most of the population is in the middle to upper middle class, with about fifty two percent white collar workers and other professionals.[30] According to the 2005 census, 32 percent work in services, 13% as street vendors and 12% as government workers. There are 122,000 residential units with 2.9 occupants on average. 99% are literate, average schooling is 12.6 years with 117,000 people with professional level studies and 16,000 with post-graduate degrees.[9] The borough was ranked with the highest standard of living in the country of Mexico according to the Consejo Nacional de Población.[7]

Most of the population of the borough originates from some other part of the country with a small population of indigenous language speakers. As of 2000, 69% of the population had migrated into the borough from other parts of Mexico, especially the states of Hidalgo, Puebla, Veracruz and Oaxaca.[30] As of 2000, there were just under 6,000 people in the borough that spoke an indigenous language, about 1.8 percent of the total, with almost all of the rest being speakers of Spanish. This ranks the borough eighth in Mexico City. Of the indigenous language speakers, just under seventy percent were women and most spoke Nahuatl at 28.5% followed by Zapotec and Otomi at 11.5 and 9.4% each.[10]

Economy

The borough's economic activity accounts for 6.2% of the total GDP of Mexico City. The largest contributing sector is construction enterprises, which make up 22.4% of the city's construction. Services, especially professional services, makes up about seventy percent of the borough's GDP, followed by construction at just over 27% and commerce at 17.4%.[7] Up to two million people come into the borough on any given day for work, shopping or to study.[36] The borough ranks second after Coyoacán in spaced dedicated to commerce at 274,366 m2.[40] Avenida Insurgentes is the most important commercial area for the borough, with a large concentration of bars and restaurants from fast food to international cuisine at all price ranges. These serve the large number of offices that house architect, lawyers and other professional services.[9]

The borough's hotel infrastructure is minimal with four out of the city's 64 five-star establishments and thirteen of its 96 four-star hotels; however, there have been recent efforts to expand tourism in the borough.[7][41] Tourist attractions include the murals of the Polyforum Cultural Siqueiros, the Secretaría de Comunicaciones y Transportes and the Insurgentes Theatre along with the archeological site at Parque Hundido, Estadio Azul and the Plaza de Toros México.[42] Three tourist routes are planned for the borough to bring visitors to the area's museums, historic sites, commercial centers, bars and restaurants via the city's Turibús. Two areas especially targeted are Narvarte and Mixcoac. This follows a recently opened permanent tourist information center established in the borough.[41]

As most of the borough is still residential, despite recent pressures to convert to commercial, much of the borough's wealth is in the earning power of its residents. 58.9% of the total population is economically active, with an unemployment rate of under one percent. Seventy seven percent are occupied in the commerce and service sectors, most of which are jobs in retail. 20.3% are employed in industry, mostly pharmaceuticals and products for industry.[7] Half of the population works between 33 and 48 hours per week with 29% working more than 48 hours per week.[10] Benito Juárez is the only borough in the city ranked with high level of socioeconomic development, compared to four ranked with a medium level, ten with a low level and one with a very low level. This ranking takes into account the basic lifestyle of families here especially size and quality of housing, access to health services and education, city services, durable goods and more.[43] Within the borough, about twenty percent of the population live in medium level conditions such as those in the Independencia, Nativitas, Portales Oriente, Residenciales and Villa de Cortés neighborhoods. However, the gap between rich and poor is significantly less than in other areas such as Cuajimalpa and Alvaro Obregon.[43] The living standards for the borough are roughly equivalent to that of the United States.[10]

Education

The borough has one of the highest education levels in Mexico City. 98.9% of the population is literate, a higher rate than Mexico City, with an average of 12.6 years of schooling.[44][7] Three percent lack primary school education; fifteen percent lack middle school; twenty nine percent lack high school and fifty five percent have not attended higher education. Gender gap in education has narrowed from 6.9 years for women compared to 10 years for men in 1980 to 9.6 years for women and 10.5 years for men in 2000.[10]

The borough has 488 schools and other educational campuses of which 147 are public and 341 are private. Public schools include thirty two early education centers, thirty six kindergartens, fifty six primary schools, twenty two middle schools, one preparatory high school, a vocational/technical high school and eighteen universities. Private institutions include one early education center, 109 kindergartens, 104 primary schools, fifty five middle schools and thirty nine preparatory high schools.[44] The borough has 6.4% of all preschools in the city, 5.2% of the primary schools, 6.5% of middle schools, 4.9% of preparatory schools and ten percent of vocational/technical schools.[7]

Colleges and universities

Primary and secondary schools

International schools include:

- Colegio Suizo de México (Schweizerschule Mexiko) – Colonia del Valle[45]

Other private schools include:

- Colegio La Salle Simón Bolívar has two campuses in Mixcoac.[46]

- Escuela Sierra Nevada – Centro Educativo Nemi in Colonia del Valle[47]

- Escuela Mexicana del Valle / Americana in Colonia del Valle

- Tomás Alva Edison School in Colonia del Valle[48]

- Instituto México Primaria in Colonia del Valle

- Instituto México Secundaria in Xoco

- Instituto Simón Bolívar in Xoco[49]

- Colegio la Florida

- Colegio Williams Mixcoac Campus[50]

- Colegio Nuevo Continente – Campus Ciudad de México in Colonia del Valle[51]

- Instituto Víctor Hugo[52]

Transportation

It has 102.5 km of primary roadway, making up 10.9% of that of Mexico City. As of 2003, there were 373,485 vehicles registered in the borough, with over 96% to private owners. This is about ten percent of all cars registered in the city.[7] There are 12,448,999 meters of paved roads with 89.90 km of these as main thoroughfares and 631.1 km of secondary roads.[5] The traffic congestion slows the pace to about ten kilometers on average and as low as 4.3 during rush hours. There are 290,346 autos registered.[28]

A dozen major roadways that cross the borough. One system of streets that criss-cross the area is the "Eje" (Axis) roads which include Eje 4 Sur, Eje 5 Sur, Eje 6 Sur, Eje 7 Sur, Eje 7-A Sur, Eje 8 Sur, Eje 3 Poniente, Eje 2 Poniente and Eje Central. In addition, part of the Circuito Interior loop passes through parts of the borough locally known as Avenida Revolución and Río Churubusco. Other major roadways include Boulevard Adolfo López Mateos (Periférico), Viaducto Miguel Alemán, Viaducto Río Becerra and Calzada de Tlalpan.[26]

There are eighteen Metro stations and forty-four bus routes.[28] In 2005, the city government built the first Metrobus line on Avenida Insurgentes. Line 1 crosses the borough between Viaducto and Barranca del Muerto stops. Since then two more Metrobus lines have been built that cross the borough as well. Line 2 crosses east-west and Line three crosses along Avenida Cuauhtémoc.[26] Several Metro lines cross the borough. Currently operating lines include Line 3, Line 9 and Line 7. Construction of a new line, Line 12, was finished in 2012. This line cuts east-west through the borough connecting Mixcoac to Tlahuac.[42]

- Metro stations

The borough is planning two major bike routes through the area in order to support a citywide effort to promote this form of transportation. These will be concentrated on Pilares and Adolfo Prieto streets, for east-west and north-south traffic respectively, connecting with bike paths in other boroughs.[53]

See also

References

- ↑ "Delegación Benito Juárez" (PDF) (in Spanish). Sistema de Información Económica, Geográfica y Estadística. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 3, 2008. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- ↑ "DelegacionBenitoJuarez.gob.mx • Datos estadísticos". Archived from the original on January 22, 2009. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- ↑ "Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020 - SCITEL" (in Spanish). INEGI. Retrieved 2021-01-27.

- ↑ PNUD México. "Índice de Desarrollo Humano Municipal en México". Portal de Información Social del Estado de Guanajuato.

- 1 2 3 4 "Límites y Colindancias" [Borders and neighboring entities] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Benito Juárez. 2009. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Los orígenes" [Origins] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Benito Juárez. 2009. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Delegación Benito Juárez" [Benito Juárez Borough] (PDF) (in Spanish). Mexico City: Secretaría del Desarrollo Económico. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 22, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Datos estadísticos" [Statistics] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Benito Juárez. 2009. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Angélica Enciso L. (February 15, 2011). "La delegación Benito Juárez, el otro extremo en índice de calidad de vida" [The Benito Juárez borough, the other extreme of the socioeconomic index]. La Jornada (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 "Breviario 2000 Benito Juárez, D.F." [Benito Juarez, Federal District Brief 2000] (PDF) (in Spanish). Mexico City: Consejo de Población del DF (COPODF). 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 16, 2012. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- 1 2 "Vivienda" [Housing] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Benito Juárez. 2009. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ↑ "World Trade Center Mexico". HIR Expo Internacional. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ↑ "Complejo WTC Torre WTC Historia" [WTC Complex, WTC Tower History] (in Spanish). Archived from the original on October 1, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Historia de la Plaza México" [History of the Plaza México] (in Spanish). Plaza de Toros México. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Estadio Azul" (in Spanish). Club Deportivo Social y Cultural Cruz Azul A.C. 2011. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ↑ "¿Qué es el Polyforum?" [Qwhat is the Polyforum?] (in Spanish). Siqueiros Foundation. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Concepción" [Conception] (in Spanish). Instituto Cultural Siqueiros. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- 1 2 "Cultura" [Culture] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Benito Juárez. 2009. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Línea Cronológica" [Time line] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Benito Juárez. 2009. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Deportivos Delegación Benito Juárez" [Benito Juarez, Federal District Sports] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Instituto del Deporte del Distrito Federal. Archived from the original on October 1, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Antecedentes Históricos" [Historical antecedents] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Benito Juárez. 2009. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ↑ Yascara Lopez (March 17, 2001). "Modificara la Delegacion Benito Juarez su logotipo" [Benito Juárez borough will modify its logo]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 "Vías de Comunicación" [Transit] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Benito Juárez. 2009. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "De la Colonia a la Reforma" [From the colonial period to the Reform era] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Benito Juárez. 2009. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "La Revolución" [The Revolution] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Benito Juárez. 2009. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- 1 2 3 "Vialidades" [Main roads] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Benito Juárez. 2009. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Siglo XX" [20th century] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Benito Juárez. 2009. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mirtha Hernandez (November 8, 2004). "Viven urbes tirania del trafico / Benito Juarez: tradicion" [Cities experience the tyranny of traffic/Benito Juarez:Tradition]. Reforma. Mexico City. p. 2.

- ↑ Distrito Federal División Territorial de 1810 a 1995 (PDF) (in Spanish). Mexico: INEGI. 1996. ISBN 970-13-1494-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Población" [Population] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Benito Juárez. 2009. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Los primeros centros comerciales de la capital". El Universal. 20 July 2018.

- 1 2 Johana Robles (June 26, 2007). "Crecen casas y disminuye población en Benito Juárez". El Universal. Mexico City. p. 1.

- ↑ Jorge Carlos Díaz Cuervo (October 19, 2007). "¿Qué le pasó a Benito Juárez?". Economista. Mexico City. p. 1.

- ↑ Lili Valadez (March 17, 2001). "Anuncian cambios a plan urbano para delegacion Benito Juarez en el DF; [Source: El Universal]" [Announce changes to the urban plan for Benito Juarez borough in Mexico City]. Noticias Financieras (in Spanish). Miami. p. 1.

- ↑ Anayansin Insunza (October 26, 2004). "Es Benito Juarez diamante del DF" [Benito Juarez is a diamond in the Federal District]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 Rafael Cabrera (July 29, 2006). "Tiene la Benito Juárez 11 colonias peligrosas". Reforma. Mexico City. p. 7.

- 1 2 Juan Corona (December 21, 2010). "Piden más policías para Benito Juárez" [Request more pólice for Benito Juarez]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 1.

- 1 2 Ricardo Rivera (December 14, 2008). "Aumentan los delitos en la Benito Juárez" [Felonies rise in Benito Juarez]. Reforma (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 7.

- ↑ Arturo Sierra (February 5, 2007). "Importa ladrones Benito Juárez" [Benito Juarez imports robbers]. Reforma. Mexico City. p. 7.

- ↑ Karla Ramirez (March 9, 2007). "Ganan Coyoacán y Benito Juárez". Reforma. Mexico City. p. 1.

- 1 2 "Destaca Sectur-DF creación de Circuitos en Benito Juárez" [Secretary of Tourism unveils the creation of tourist routes in Benito Juárez]. Radio Formula (in Spanish). Mexico City. June 21, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- 1 2 Karla Mora (June 22, 2011). "Fotos: Trabaja "La Rielera" de L12 en Eje Central" [Photos: "La Rielera" of Line 12 at Eje Central]. El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- 1 2 Jessica Castillejos (April 14, 2011). "La Benito Juárez alcanzó el nivel alto en desarrollo social" [Benito Juárez reached a high level of socioeconomic development]. El Excelsior (in Spanish). Mexico City. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- 1 2 "Educación" [Education] (in Spanish). Mexico City: Borough of Benito Juárez. 2009. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Contact." Colegio Suizo de México. Retrieved on 14 March 2014. "CAMPUS MÉXICO El Colegio Europeo en la Colonia del Valle Nicolás San Juan 917 Col. Del Valle C.P. 03100, México D.F." and "CAMPUS CUERNAVACA El Colegio Europeo en Cuernavaca Calle Amates s/n Col. Lomas de Ahuatlán C.P. 62130, Cuernavaca, Morelos." and "CAMPUS QUERÉTARO El Colegio Europeo en Querétaro Circuito la Cima No. 901 Fracc. La Cima C.P. 76146, Querétaro, Querétaro"

- ↑ "Contacto." Colegio La Salle Simón Bolívar. Retrieved on April 14, 2016. "Galicia #8 Col. Insurgentes Mixcoac C.P. 03920 México, D.F." and "Av. Río Mixcoac #275 Col. Florida C.P. 01030 México, D.F."

- ↑ "Contact Archived 2016-11-10 at the Wayback Machine." Escuela Sierra Nevada. Retrieved on April 5, 2016. "Centro Educativo Nemi Gabriel Mancera 733, Col. del Valle, Benito Juárez México D.F. CP 03810 "

- ↑ "TAE Profile." Tomás Alva Edison School. p. 4. Retrieved on April 14, 2016. "Preschool Heriberto Frías 1407 Colonia del Valle México, D.F., C.P. 03100" and "Elementary School Manzanas 11 Colonia del Valle México, D.F., C.P. 03100" and "Middle School Amores 1213 Colonia del Valle México, D.F., C.P. 03100" and "High School Heriberto Frías 1401 Colonia del Valle México, D.F., C.P. 03100"

- ↑ "Dirección" (Archive). Instituto Simón Bolívar. Retrieved on May 31, 2014. "Mayorazgo de Solís no. 65, Col. Xoco Del. Benito Juárez CP. 03330 Distrito Federal."

- ↑ "CAMPUS Archived June 11, 2016, at the Wayback Machine." Colegio Williams. Retrieved on April 15, 2016. "Campus Mixcoac Empresa No. 8 Col. Mixcoac Deleg. Benito Juárez México D.F., C.P. 03910"

- ↑ "Inicio." Colegio Nuevo Continente. Retrieved on April 20, 2016. "Nicolás San Juan No. 1141, Col. Del Valle, México DF. CP. 03100"

- ↑ "Instituto Victor Hugo. Retrieved on June 20, 2023. "DR. BARRAGAN, 518, COL NARVARTE, BENITO JUAREZ, DF, C.P. 03020"

- ↑ Angelica Simon (April 20, 2006). "Cruzarán 2 ciclopistas la delegación Benito Juárez" [Two bicycle lanes will cross the Benito Juárez borough]. El Universal (in Spanish). Mexico City. p. 1.

External links

- (in Spanish) Alcaldía de Benito Juárez website