Beeldenstorm (pronounced [ˈbeːldə(n)ˌstɔr(ə)m]) in Dutch and Bildersturm [ˈbɪldɐˌʃtʊʁm] in German (roughly translatable from both languages as 'attack on the images or statues') are terms used for outbreaks of destruction of religious images that occurred in Europe in the 16th century, known in English as the Great Iconoclasm or Iconoclastic Fury and in French as the Furie iconoclaste. During these spates of iconoclasm, Catholic art and many forms of church fittings and decoration were destroyed in unofficial or mob actions by Calvinist Protestant crowds as part of the Protestant Reformation.[2][3] Most of the destruction was of art in churches and public places.[4]

The Dutch term usually specifically refers to the wave of disorderly attacks in the summer of 1566 that spread rapidly through the Low Countries from south to north. Similar outbreaks of iconoclasm took place in other parts of Europe, especially in Switzerland and the Holy Roman Empire in the period between 1522 and 1566, notably Zürich (in 1523), Copenhagen (1530), Münster (1534), Geneva (1535), and Augsburg (1537).[5]

In England, there was both government-sponsored removal of images and also spontaneous attacks from 1535 onwards, and in Scotland from 1559.[5] In France, there were several outbreaks as part of the Wars of Religion from 1560 onwards.

Background

In France, unofficial episodes of large scale destruction of art in churches by Huguenot Calvinists had begun in 1560; unlike in the Low Countries, they were often physically resisted and repulsed by Catholic crowds, but were to continue throughout the French Wars of Religion.[6] In Anglican England much destruction had already taken place in an organized fashion under orders from the government,[7] while in Northern Europe, groups of Calvinists marched through churches and removed images, a move which "provoked reactive riots by Lutheran mobs" in Germany and "antagonized the neighbouring Eastern Orthodox" in the Baltic region.[2][8]

In Germany, Switzerland and England, conversion to Protestantism had been enforced on the whole population at the level of a city, principality or kingdom, with varying degrees of discrimination, persecution or expulsion applied to those who insisted on remaining Catholic. The Low Countries, Flanders, Brabant and Holland[9] were part of the inheritance of Philip II of Spain, who was a devout Catholic and self-proclaimed protector of the Counter-Reformation; he suppressed Protestantism through his Governor-general Margaret of Parma, the illegitimate daughter of Emperor Charles V, who was herself more willing to compromise. Protestants so far represented only a relatively small proportion of the Netherlandish population, but including disproportionate numbers from the nobility and upper bourgeoisie; nevertheless, but the Catholic Church had evidently lost the loyalty of the population, and traditional Catholic anti-clericalism was now dominant.[10]

The region affected was perhaps the richest in Europe, but still seethed with economic discontent among parts of the population, and had suffered a poor harvest and hard winter. However, recent historians are generally less inclined to see the movement as prompted by these factors than was the case a few decades ago.[11][12]

.jpg.webp)

The Beeldenstorm grew out of a turn in the behaviour of Low Country Protestants starting around 1560, who became increasingly open in their religion, despite penal sanctions. Catholic preachers were interrupted in sermons, and raids were organized to rescue Protestant prisoners from jail, who then often fled into exile in France or England. Protestant views were spread by a large movement of "field sermons" or open-air sermons (Dutch: hagepreken) held outside towns, and therefore out of the jurisdiction of the town authorities. The first took place on the Cloostervelt near Hondschoote, in what is now the arrondissement of Dunkirk in French Flanders, very close to where the attacks later began, and the first one to be armed against disruption was held near Boeschepe on 12 July 1562, two months after religious war had broken out again over the (then) French border just nearby.[13]

These open-air sermons, mostly by Anabaptist or Mennonite preachers, spread through the country, attracting huge crowds, though not necessarily of those leaning to Protestantism, and in many places immediately preceded the iconoclastic attacks of August 1566. Prosecutions for heresy continued, especially in the south, although they were erratic, and in some places clergy of clearly heretical views were appointed to churches. By 1565 the authorities seem to have realized that persecution was not the answer, and the level of prosecutions slackened, and the Protestants became increasingly confident in the open.[14] A letter of 22 July 1566 from local officials to the Regent, warned that "the scandalous pillage of churches, monasteries and abbeys" was imminent.[15]

Low Countries iconoclastic attacks in 1566

On 10 August 1566, the feast-day of Saint Lawrence, at the end of the pilgrimage from Hondschoote to Steenvoorde, the chapel of the Sint-Laurensklooster was defaced by a crowd who invaded the building. It has been suggested that the rioters connected the saint especially with Philip II, whose monastery palace of the Escorial near Madrid was dedicated to Lawrence, and was just nearing completion in 1566.[16] Iconoclastic attacks spread rapidly northwards and resulted in the destruction of not only images but all sorts of decoration and fittings in churches and other church or clergy property. However, there was relatively little loss of life, unlike similar outbreaks in France, where the clergy were often killed, and some iconoclasts too.[17]

The attacks reached the commercial centre of the Low Countries, Antwerp, on 20 August, and on 22 August Ghent, where the cathedral, eight churches, twenty-five monasteries and convents, ten hospitals and seven chapels were wrecked. From there, it further spread east and north, reaching Amsterdam, then a much smaller town, by 23 August, and continuing in the far north and east into October, although the main towns were mostly attacked in August. Valenciennes ("Valencijn" on the map) was the most southerly town attacked. In the east, Maastricht on 20 September and Venlo on 5 October saw attacks, but generally the outbreaks were restricted to more westerly and northern areas.[18] Over 400 churches were attacked in Flanders alone.[19]

The eye-witness Richard Clough, a Welsh Protestant merchant then in Antwerp, saw: "all the churches, chapels and houses of religion utterly defaced, and no kind of thing left whole within them, but broken and utterly destroyed, being done after such order and by so few folks that it is to be marvelled at." The Church of Our Lady in Antwerp, later made the cathedral (illustrated at top): "looked like a hell, with above 10,000 torches burning, and such a noise as if heaven and earth had got together, with falling of images and beating down of costly works, such sort that the spoil was so great that a man could not well pass through the church. So that in fine [short], I cannot write you in x sheets of paper the strange sight I saw there, organs and all destroyed."[20][21]

Nicolas Sander, an English Catholic exile who was a professor of theology at Louvain, described the destruction in the same church:

... these fresh followers of this new preaching threw down the graven [sculpted] and defaced the painted images, not only of Our Lady but of all others in the town. They tore the curtains, dashed in pieces the carved work of brass and stone, brake the altars, spoilt the clothes and corporesses, wrested the irons, conveyed away or brake the chalices and vestiments, pulled up the brass of the gravestones, not sparing the glass and seats which were made about the pillars of the church for men to sit in. ... the Blessed Sacrament of the altar ... they trod under their feet and (horrible it is to say!) shed their stinking piss upon it ... these false bretheren burned and rent not only all kind of Church books, but, moreover, destroyed whole libraries of books of all sciences and tongues, yea the Holy Scriptures and the ancient fathers, and tore in pieces the maps and charts of the descriptions of countries.[22]

Such details are corroborated by many other sources. Accounts of the actions of the iconoclasts from eyewitnesses and the records of the later trials of many of them make it clear that there was often a considerable element of carnival to the outbreaks, with much mockery of the images and fittings such as fonts recorded as the iconoclasts went about their work. Alcohol features largely in very many accounts, perhaps in some cases because in Netherlandish law being drunk could be regarded as a mitigating factor in criminal sentencing.[23]

The destruction frequently included ransacking the priest's house, and sometimes private houses suspected of sheltering church goods. There was much looting of common household goods from clergy houses and monasteries, and some street robberies of women's jewellery by the crowd; after the images were smashed and the property occupied, "men fed their stomachs in a carnivalesque indulgence of beer, bread, butter and cheese, while women carted off provisions for the kitchen or bedroom".[24]

There are many accounts of rituals of inversion, in which the church sometimes stood for the whole social order. Children sometimes participated enthusiastically, and street games afterwards became play battles between "papists" and "beggars". One child was killed in Amsterdam by a stone thrown in such a game.[25] Elsewhere the iconoclasts seemed to treat their actions as a job of work; in one city the group waited for the bell rung to mark the start of the working day before beginning their work. The tombs and memorial inscriptions of the patriciate and nobility, and in some cases royalty, were defaced or destroyed in several places, although secular public buildings such as town halls, and the palaces of the nobility, were not attacked.[26] In Ghent, on the one hand the memorial in a church to Charles V's sister Isabel (and so Philip's aunt) was carefully left alone, but a statue in the street of Charles V and the Virgin was destroyed.[27]

The actions were controversial among Protestants, some of whom implausibly tried to blame Catholic agent provocateurs,[28] as it became clear that "the more popular elements of the dissident movement were out of control".[29] Protestant ministers and activists returning from exile in England and elsewhere played a significant role, and individual wealthy Protestants were widely suspected of hiring men to do the work in some places, especially Antwerp.[30]

In some rural areas gangs of iconoclasts moved across country between village churches and monasteries for several days.[4][31] Elsewhere there were large crowds involved, sometimes locals, and sometimes from outside the area. In some places the nobility gave assistance, ordering the clearing of churches on their estates. Local magistracies were often opposed, but ineffective in stopping the destruction.[32] In many towns the archer's guild, who had a function in controlling public order, took no steps against the crowds.[33]

In 1566, unlike the situation after the Eighty Years' War and today, Protestantism in the Low Countries was mainly concentrated in the south (roughly modern Belgium), and much weaker in the north (roughly now the Netherlands). Iconoclasm in the north began later, after news of the events in Antwerp was received, and was more successfully resisted by local authorities in some towns, though still succeeding in most.[34] Once again socially prominent laymen often took the lead.[35] In many places there were, or were later said to have been, false claims of official commissions from some local authority to perform the actions, and by the end of the outbreak some northern towns removed images by order of the local authority, presumably to prevent the disorder that would accompany a mob action.[36]

Analysis of the records of the later trials shows a wide range of occupations, covering craftsmen and small tradespeople, especially in the textile trade, and also a variety of church employees, at a fairly low level. Where wealth and property are recorded, it is "modest at best".[37]

"Stille beeldenstorm" of 1581 in Antwerp

Antwerp experienced a further period of iconoclasm in 1581, after a Calvinist city council was elected and purged the city's clergy and guilds of Catholic office-holders. This is known as the "quiet" or "stille" beeldenstorm, as the removal of images was carried out by the institutions they belonged to, the council itself, churches and the guilds. Some images were sold rather than destroyed, but most seem to have been lost. In the summer of 1584 Antwerp was besieged by the Duke of Parma's Spanish army, falling a year later.[38]

Artistic losses

Rarely was any thought given to the artistic heritage of these cities in 1566, though families were sometimes able to protect the church monuments of their ancestors, and in Delft the syndics of the painters' Guild of Saint Luke were able to rescue the altarpiece by Maarten van Heemskerck, which the guild had commissioned only 15 years earlier.[39]

The van Eycks' Ghent Altarpiece, then as now famous as a supreme example of Early Netherlandish painting and already a major tourist attraction, just restored in 1550, was saved by dismantling it and hiding it in the cathedral tower. A first attack on 19 August was deterred by a small number of guards. When a larger attack was made at night two days later the iconoclasts had provided themselves with a tree trunk as a battering ram, and succeeded in breaking through the doors.[40]

By then the panels had been removed from the frame and hidden, with the guards, on the narrow spiral staircase up the tower, with a locked door at ground level. They were not detected and the crowd left after destroying what else they could find.[40] The panels were then moved to the town hall, and only returned to view in 1569, by which time the elaborate frame had disappeared.[41] The artistic and literary losses were elaborately described by Marcus van Vaernewyck in his journal Van die beroerlicke tijden in die Nederlanden en voornamelick in Ghendt 1566-1568. The original manuscript of his journal is still preserved in the Ghent University Library.[42]

Despite militia guards, two of the three main churches in Leiden were attacked; in the Pieterskerk the choirbooks and altarpiece by Lucas van Leyden were preserved.[43] In the Oude Kerk in Amsterdam an altarpiece with a central panel by Jan van Scorel and side panels painted on both sides by Maarten van Heemskerck was lost.[44] The most important works of several painters, especially those like Pieter Aertsen who worked in Antwerp,[45] were all destroyed, leading to a somewhat distorted view of the art history of the period. An altarpiece in Culemborg had been commissioned in 1557 from the painter Jan Dey, was then destroyed in 1566 and in 1570 recommissioned from Dey, apparently as a copy of the first. However the new work was only in place for five years before it was removed when the town went officially Calvinist.[46]

Consequences

On 23 August Margaret of Parma, the Habsburg Regent or Governor-general, whose capital of Brussels was unaffected by the movement, agreed to an "Accord" with the group of aristocratic Protestant leaders known as the "Compromise" or Geuzen ("Beggars"), by which freedom of religion was granted, in exchange for allowing Catholics to worship unmolested and an end to the violence. Instead, "the outbreak of the iconoclastic fury began an almost uninterrupted series of skirmishes, campaigns, plunder, pirate-raids, and other acts of violence. Not all areas suffered violence at the same time or to the same extent, but practically none remained unscathed."[47]

Many elite Protestants were now alarmed by the forces unleashed, and some of the nobility began to shift towards support of the government. Implementing the somewhat vague terms of the agreement led to further tensions, and William of Orange, appointed by Margaret to resolve the situation in Antwerp, tried and failed to produce a wider settlement that all parties could live with. Instead unrest continued and the episode fed into the causes of the Dutch Revolt which was to erupt two years later.[48]

On 29 August 1566 Margaret wrote a somewhat panicked letter to Philip, "claiming that half the population were infected with heresy, and that over 200,000 people were up in arms against her authority".[49] Philip decided to send the Duke of Alba with an army; he would have led them himself but was kept in Spain by other matters, especially the increasingly evident insanity of his heir, Carlos, Prince of Asturias.[50] When Alba arrived the following year, and soon replaced Margaret as Governor-general, his heavy-handed repression, which included the execution of many convicted of iconoclastic attacks the summer before, only made the situation worse.[49]

Antwerp was then Europe's largest financial and international trading centre, taking as much as 75 or 80% of English exports of cloth,[51] and the disturbances created serious and well-justified fears that its position as such was under threat. Sir Thomas Gresham, the English financier who arranged Elizabeth I's borrowings, and whose agent in Antwerp was Clough, left London for Antwerp on 23 August, only hearing about the Antwerp attacks en route; he needed to roll-over 32,000 Flemish pounds and borrow another 20,000 to finance her expenses in Ireland. Dining with William of Orange on his arrival, he was asked if "the English were minded to depart this town or not", and wrote to William Cecil, Elizabeth's chief minister, "in alarm that he "liked none of their proceedings" but "apprehended great mischief", and urged that the English government "should do very well in time to consider some other realm and place" for marketing English products. It was a message that helped shape the course of events."[52]

The English had found the Antwerp money market short of funds since earlier in the year, and now made use of Cologne and Augsburg as well, but as events unfolded in the next year, and the personal position of some leading lenders became precarious, the English found to their surprise that repayments were no longer pressed for, probably as the lenders were happy to keep their money abroad on loan to a secure borrower.[53] The Dutch Revolt, which from 1585 onwards included a Dutch blockade of the River Scheldt leading to the city, was to finally destroy Antwerp as a major trading centre.

In many places there were attempts by Calvinist preachers to take over the ransacked buildings. These were usually repulsed in the period after the attacks. In the months afterwards there were attempted negotiations in many cities, by William of Orange and others, to allocate certain churches to accommodate the local Protestants, often divided into Lutherans and Calvinists. These had mostly failed within a few weeks, not least because Margaret's government rejected them; she had already had an earlier attempt at compromise overruled by Philip a few months earlier, and been embarrassingly forced to retract a decree.[54] Instead there was a wave of building or adapting Calvinist "temples", though in the end none of these were to remain in use by the following year, and their layouts, which seem to have echoed early Swiss and Scottish Calvinist designs, are now largely unknown.[55]

Once the revolt proper had started, there were many further instances of clearing churches, some still unofficial and disorderly, but as cities became officially Protestant, increasingly undertaken by official order, like the Amsterdam Alteratie ("Alteration") of 1578. Altars, to which Calvinists, unlike Lutherans, took strong exception, were typically completely removed, and in some large churches, like Utrecht Cathedral, large tomb monuments put where they stood, partly to make their return more difficult if political conditions changed. As the Eighty Years' War concluded, in the cities and areas that had become Protestant, the old Catholic churches were nearly all taken over by the new established faith, the Calvinist Dutch Reformed Church, while other congregations were left to find their own buildings.[56]

The bare and empty state of those churches left in Catholic hands after the hostilities eventually ended prompted a large programme of restocking with Catholic art, which had much to do with the vigour of Northern Mannerism and later Flemish Baroque painting, and many Gothic churches were given Baroque makeovers.[57] In the north, now strongly Protestant, religious art largely disappeared, and Dutch Golden Age painting concentrated on a wide range of secular subjects, such as genre painting, landscape art and still-lifes, with results that might sometimes have surprised the Protestant ministers who initiated the movement. According to one scholar, this "was not only a dramatic change in the function of art, it was the context in which our present concept of art, what the literary critic M. H. Abrams called "art as such", first began to take shape", replacing a "construction model" where art theory concerned itself with how makers created their works, with a "contemplation model" concerned with the effect of finished works on a "lone perceiver" or viewer.[58]

Images

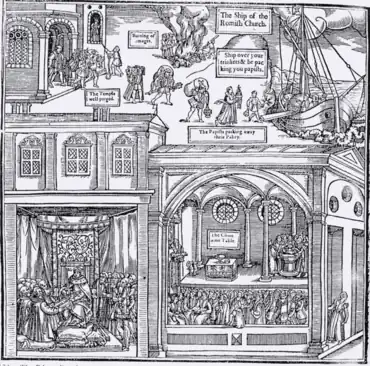

Woodcut of 1563 from Foxe's Book of Martyrs

Woodcut of 1563 from Foxe's Book of Martyrs Defaced tomb effigy of Bishop Guy of Avesnes, Utrecht cathedral

Defaced tomb effigy of Bishop Guy of Avesnes, Utrecht cathedral

See also

Notes

- ↑ analysed in Arnade, 146 (quoted); see also Art through time Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Marshall, Peter (22 October 2009). The Reformation. Oxford University Press. p. 98. ISBN 9780191578885.

Iconoclastic incidents during the Calvinist 'Second Reformation' in Germany provoked reactive riots by Lutheran mobs, while Protestant image-breaking in the Baltic region deeply antagonized the neighbouring Eastern Orthodox, a group with whom reformers might have hoped to make common cause.

- ↑ Byfield, Ted (2002). A Century of Giants, A.D. 1500 to 1600: In an Age of Spiritual Genius, Western Christendom Shatters. Christian History Project. p. 297. ISBN 9780968987391.

Devoutly Catholic but opposed to Inquisition tactics, they backed William of Orange in subduing the Calvinist uprising of the Dutch beeldenstorm on behalf of regent Margaret of Parma, and had come willingly to the council at her invitation.

- 1 2 Kleiner, Fred S. (1 January 2010). Gardner's Art through the Ages: A Concise History of Western Art. Cengage Learning. p. 254. ISBN 9781424069224.

In an episode known as the Great Iconoclasm, bands of Calvinists visited Catholic churches in the Netherlands in 1566, shattering stained-glass windows, smashing statues, and destroying paintings and other artworks they perceived as idolatrous.

- 1 2 John Phillips, Reformation of Images: Destruction of Art in England, 1535–1660, (Berkeley: University of California Press) 1973.

- ↑ Eire, 279–280

- ↑ Buchanan, Colin (4 August 2009). The A to Z of Anglicanism. Scarecrow Press. p. 26. ISBN 9780810870086.

Royal Injunctions order the reading of biblical passages in English at the mass, along with the destruction of images and the provision of a "poor men's box" for alms.

- ↑ Lamport, Mark A. (31 August 2017). Encyclopedia of Martin Luther and the Reformation. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 138. ISBN 9781442271593.

Lutherans continued to worship in pre-Reformation churches, generally with few alterations to the interior. It has even been suggested that in Germany to this day one finds more ancient Marian altarpieces in Lutheran than in Catholic churches. Thus in Germany and in Scandinavia many pieces of medieval art and architecture survived. Joseph Leo Koerner has noted that Lutherans, seeing themselves in the tradition of the ancient, apostolic church, sought to defend as well as reform the use of images. "An empty, white-washed church proclaimed a wholly spiritualized cult, at odds with Luther's doctrine of Christ's real presence in the sacraments" (Koerner 2004, 58). In fact, in the 16th century some of the strongest opposition to destruction of images came not from Catholics but from Lutherans against Calvinists: "You black Calvinist, you give permission to smash our pictures and hack our crosses; we are going to smash you and your Calvinist priests in return" (Koerner 2004, 58). Works of art continued to be displayed in Lutheran churches, often including an imposing large crucifix in the sanctuary, a clear reference to Luther's theologia crucis. ... In contrast, Reformed (Calvinist) churches are strikingly different. Usually unadorned and somewhat lacking in aesthetic appeal, pictures, sculptures, and ornate altar-pieces are largely absent; there are few or no candles; and crucifixes or crosses are also mostly absent.

- ↑ What is now approximately Belgian Limburg was part of the Bishopric of Liège and ruled by the bishop (shown in brown on the map).

- ↑ Elliott, 90–91

- ↑ Arnade, 95–98, and 116, especially note 105 (where "reputation" is presumably a misprint for "refutation"). Elliott, 89–91, first written in 1968, reflects a version of the older view, for which the German Marxist historian Erich Kuttner was the standard-bearer.

- ↑ Pollmann, 170–175.

- ↑ Petegree, 74–75

- ↑ Petegree, 82–86

- ↑ Arnade, 97

- ↑ Arnade, 103–104

- ↑ Arnade, 116

- ↑ See map with dates in Petegree, 118; Arnade, 90–91

- ↑ Eire, 280

- ↑ Spicer, 109 (spelling modernized); see also Arnade, 146–148

- ↑ Eye-witness Account of Image-breaking at Antwerp, Universiteit Leiden Archived 2012-07-09 at archive.today

- ↑ Miola, 58–59, 59 quoted

- ↑ Arnade, 105–111

- ↑ Arnade, 111–112 (quote from 112); 102 for women's jewellery robbed.

- ↑ Arnade, 111–114; for the whole paragraph: 104–122

- ↑ Arnade, 116–124

- ↑ Arnade, 119–120

- ↑ Petegree, 117–119

- ↑ Wells, 91

- ↑ Petegree, 116–117, and elsewhere, on returning exiles; Arnade, 146–147 on paid iconoclasts

- ↑ Arnade, 101–102; 104–109

- ↑ Petegree, 119–124; Arnade, 120–122

- ↑ Arnade, 120

- ↑ Brouwer, Maria (11 August 2016). Governmental Forms and Economic Development: From Medieval to Modern Times. Springer. p. 224. ISBN 9783319420400.

The city of Amsterdam pursued a policy of restraint against the Calvinists. The iconoclast movement reached Amsterdam in August 1566, but the city government had moved and stored away many church possessions before the iconoclasts reached the city. All churches were closed to tame the fury.

- ↑ Petegree, 124–128

- ↑ Arnade, 120–122

- ↑ Arnade, 102

- ↑ Freedberg, 133

- ↑ Montias, 4

- 1 2 Charney, 72–73 - a populist account; when he says April he means August, and "The Lamb" refers to the altarpiece. Petegree, 118 has the Beeldenstorm reaching Ghent on 22 August. See also Arnade, 118

- ↑ Ridderbos, Bernhard; Veen, Henk Th van; Buren, Anne van (25 March 2018). Early Netherlandish Paintings: Rediscovery, Reception and Research. Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9789053566145 – via Google Books.

- ↑ "Van die beroerlicke tijden in die Nederlanden /Marcus Van Vaernewijck[manuscript]". lib.ugent.be. Retrieved 2020-08-24.

- ↑ "Iconoclasm - Pieterskerk Leiden". 10 September 2012. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012.

- ↑ Stechow, Wolfgang (25 March 1966). Northern Renaissance Art, 1400-1600: Sources and Documents. Northwestern University Press. ISBN 9780810108493 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Gustav Friedrich Waagen,

- ↑ Jacobs, Lynn F., review of Liesbeth M. Helmus, Schilderen in opdracht: Noord-Nederlandse contracten voor altaarstukken 1485–1570. Utrecht: Centraal Museum, 2010, ISBN 978-90-5983-021-9. Historians of Netherlandish art website. accessed 4 March 2011 Archived 26 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Lesger, 110

- ↑ Elliott, 91–93; Petegree, 132–134; Wells, 89–91; Arnade, 100

- 1 2 Luu, Liên (25 March 2018). Immigrants and the Industries of London, 1500-1700. Ashgate. ISBN 9780754603306 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Gelderen, Martin van (3 October 2002). The Political Thought of the Dutch Revolt 1555-1590. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521891639 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Ramsay, 62–63

- ↑ Ramsay, 50

- ↑ Ramsay, 50–51

- ↑ Ramsay, 48

- ↑ Spicer, 110–118

- ↑ Spicer, 116–124, and following pages

- ↑ Vlieghe, 4, 13

- ↑ Wagner (short quotes from Abrams), 131

References

- Arnade, Peter J., Beggars, Iconoclasts, and Civic Patriots: the Political Culture of the Dutch Revolt, Cornell University Press, 2008, ISBN 0-8014-7496-5, ISBN 978-0-8014-7496-5

- Charney, Noah, Stealing the Mystic Lamb: The True Story of the World's Most Coveted Masterpiece, PublicAffairs, 2010, ISBN 1-58648-800-7, ISBN 978-1-58648-800-0

- Eire, Carlos M.N., War Against the Idols: The Reformation of Worship from Erasmus to Calvin, Cambridge University Press, 1989, ISBN 0-521-37984-9, ISBN 978-0-521-37984-7

- Elliott, J. H., Europe divided, 1559–1598, many edns, pages refs from Blackwell classic histories of Europe, Wiley-Blackwell, 2nd edn. 2000 (1st edn 1968), ISBN 0-631-21780-0, ISBN 978-0-631-21780-0

- Freedberg, David, "Painting and the Counter-Reformation", from the catalogue to The Age of Rubens, 1993, Boston/Toledo, Ohio, doi:10.7916/D8639ZTP

- Lesger, Clé, The rise of the Amsterdam market and information exchange: merchants, commercial expansion and change in the spatial economy of the Low Countries, c. 1550–1630, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2006, ISBN 0-7546-5220-3, ISBN 978-0-7546-5220-5

- Miola, Robert S, Early modern Catholicism: an anthology of primary sources, Oxford University Press, 2007, ISBN 0-19-925985-2, ISBN 978-0-19-925985-4

- Montias, John Michael, Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History, Princeton University Press, 1991, ISBN 0-691-00289-4, ISBN 978-0-691-00289-7

- Petegree, Andrew, Emden and the Dutch revolt: exile and the development of reformed Protestantism, Oxford University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-19-822739-6, ISBN 978-0-19-822739-7

- Pollmann, Judith, "Iconoclasts Anonymous: Why did it take Historians so long to identify the Image-breakers of 1566?". BMGN: Low Countries Historical Review, vol. 131, no. 1, March 2016, pp. 155–176, doi:10.18352/bmgn-lchr.10184

- Ramsay, George Daniel, The Queen's merchants and the revolt of the Netherlands: the end of the Antwerp mart, Part 2 of The end of the Antwerp mart, Manchester University Press, 1986, ISBN 0-7190-1849-8, ISBN 978-0-7190-1849-7

- Spicer, Andrew, Calvinist churches in early modern Europe, Manchester University Press, 2007, ISBN 0-7190-5487-7, ISBN 978-0-7190-5487-7

- Vlieghe, H., Flemish art and architecture, 1585–1700. Yale University Press Pelican history of art, 1998, Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-07038-1

- Wagner, Roger, "Art and Faith", Ch. 10 in: Harries, Richard and Brierley, Michael W. (eds), Public life and the place of the church: reflections to honour the Bishop of Oxford, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd, 2006, ISBN 0-7546-5301-3, ISBN 978-0-7546-5301-1

- Wells, Guy, "The Unlikely Machiavellian: William of Orange and the Princely Virtues", in Mack, Phyllis and Jacob, Margaret C. (eds), Politics and Culture in Early Modern Europe: Essays in Honour of H. G. Koenigsberger, Cambridge University Press, 1987, ISBN 0-521-52702-3, ISBN 978-0-521-52702-6

Further reading

- Duke, Alastair, "Calvinists and 'Papist Idolatry': The Mentality of the Image-breakers in 1566", in Pollmann, Judith and Spicer, Andrew (eds), Dissident Identities in the Early Modern Low Countries, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd, 2009, ISBN 978-0-7546-5679-1

- Freedberg, David, Iconoclasm and painting in the revolt of the Netherlands, 1566–1609, Garland, 1988 ISBN 978-0-8240-0087-5