| Taenia saginata | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Platyhelminthes |

| Class: | Cestoda |

| Order: | Cyclophyllidea |

| Family: | Taeniidae |

| Genus: | Taenia |

| Species: | T. saginata |

| Binomial name | |

| Taenia saginata Goeze, 1782 | |

Taenia saginata (synonym Taeniarhynchus saginatus), commonly known as the beef tapeworm, is a zoonotic tapeworm belonging to the order Cyclophyllidea and genus Taenia. It is an intestinal parasite in humans causing taeniasis (a type of helminthiasis) and cysticercosis in cattle. Cattle are the intermediate hosts, where larval development occurs, while humans are definitive hosts harbouring the adult worms. It is found globally and most prevalently where cattle are raised and beef is consumed. It is relatively common in Africa, Europe, Southeast Asia, South Asia, and Latin America.[1] Humans are generally infected as a result of eating raw or undercooked beef which contains the infective larvae, called cysticerci. As hermaphrodites, each body segment called proglottid has complete sets of both male and female reproductive systems. Thus, reproduction is by self-fertilisation. From humans, embryonated eggs, called oncospheres, are released with faeces and are transmitted to cattle through contaminated fodder. Oncospheres develop inside muscle, liver, and lungs of cattle into infective cysticerci.[2]

T. saginata has a strong resemblance to the other human tapeworms, such as Taenia asiatica and Taenia solium, in structure and biology, except for few details. It is typically larger and longer, with more proglottids, more testes, and higher branching of the uteri. It also lacks an armed scolex unlike other Taenia. Like the other tapeworms, it causes taeniasis inside the human intestine, but does not cause cysticercosis. Its infection is relatively harmless and clinically asymptomatic.[3][4]

Description

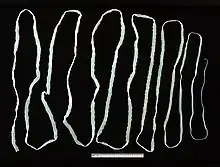

T. saginata is the largest of species in the genus Taenia. An adult worm is normally 4 to 10 m in length, but can become very large; specimens over 22 m long are reported. Typical of cestodes, its body is flattened dorsoventrally and heavily segmented. It is entirely covered by a tegument. The body is white in colour and consists of three portions: scolex, neck, and strobila. The scolex has four suckers, but they have no hooks. Lack of hooks and a rostellum is an identifying feature from other Taenia species.[4] The rest of the body proper, the strobila, is basically a chain of numerous body segments called proglottids. The neck is the shortest part of the body, and consists of immature proglottids. The midstrobila is made of mature proglottids that eventually lead to the gravid proglottids, which are at the posterior end. An individual can have as many as 1000 to 2000 proglottids.[5]

T. saginata does not have a digestive system, mouth, anus, or digestive tract. It derives nutrients from the host through its tegument, as the tegument is completely covered with absorptive hair-like microtriches. It is also an acoelomate, having no body cavity. The inside of each mature proglottid is filled with muscular layers and complete male and female reproductive systems, including the tubular unbranched uterus, ovary, genital pore, testes, and vitelline gland. In the gravid proglottid, the uterus contains up to 15 side branches filled with eggs.[3][6]

Life cycle

Intermediate host

Cattle acquire the embryonated eggs, the oncospheres, when they eat contaminated food. Oncospheres enter the duodenum, the anterior portion of the small intestine, and hatch there under the influence of gastric juices. The embryonic membranes are removed, liberating free hexacanth ("six-hooked") larvae. With their hooks, they attach to the intestinal wall and penetrate the intestinal mucosa into the blood vessels. The larvae can move to all parts of the body by the general circulatory system, and finally settle in skeletal muscles within 70 days. Inside the tissue, they cast off their hooks and instead develop a protective cuticular shell, called the cyst. Thus, they become fluid-filled cysticerci. Cysterci can also form in lungs and liver. The inner membrane of the cysticercus soon develops numerous protoscolices (small scolices) that are invertedly attached to the inner surface. The cysticercus of T. saginata is specifically named cysticercus bovis to differentiate from that of T. solium, cysticercus cellulosae.[3][6]

Definitive host

Humans contract infective cysticerci by eating raw or undercooked meat. Once reaching the jejunum, the inverted scolex becomes evaginated to the exterior under stimuli from the digestive enzymes of the host. Using the scolex, it attaches to the intestinal wall. The larva mature into adults about 5 to 12 weeks later. Adult worms can live about 25 years in the host.[3] Usually, only a single worm is present at a time, but multiple worms are also reported. In each mature proglottid, self-fertilisation produces zygotes, which divide and differentiate into embryonated eggs called oncospheres. With thousands of oncospheres, the oldest gravid proglottids detach. Unlike in other Taenia, gravid proglottids are shed individually. In some cases, the proglottid ruptures inside the intestine, and the eggs are released. The free proglottids and liberated eggs are removed by peristalsis into the environment. On the ground, the proglottids are motile and shed eggs as they move. These oncospheres in an external environment can remain viable for several days to weeks in sewage, rivers, and pastures.[3][6][7]

Genome

Epidemiology

The disease is relatively common in Africa, some parts of Eastern Europe, the Philippines, and Latin America.[2] There is also a widespread occurrence of the parasite throughout East, Southeast, and South Asia.[8] This parasite is found anywhere where beef is eaten, including countries such as the United States, with strict federal sanitation policies. In the US, the incidence of infection is low, but 25% of cattle sold are still infected.[6] However, not all slaughterhouses are federally inspected.[9] The total global infection is estimated to be between 40 and 60 million.[1] It is most prevalent in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East.[7]

Religious beliefs may also play a role in infection rates. In India, Muslims can have a higher rate of infection compared to Hindus, who do not eat beef.[9]

Infection

Symptoms

T. saginata infection is usually asymptomatic, but heavy infection often results in weight loss, dizziness, abdominal pain, diarrhea, headaches, nausea, constipation, chronic indigestion, and loss of appetite. Intestinal obstruction in humans can be alleviated by surgery. The tapeworm can also expel antigens that can cause an allergic reaction in the individual.[10] It is also a rare cause of ileus, pancreatitis, cholecystitis, and cholangitis.[11] Taenia saginata has been reported as a cause of gallbladder perforation if left untreated in some cases.[12] Taenia saginata adult worms can live in the host for up to 25 years and most infections will last 2 to 3 years without treatment.[13]

The Taenia saginata remains asymptomatic due to the fact the organism does not present cysticerci in humans. Therefore, there is no presence of cysticercosis in humans either. Typically, cysticercosis is a parasitical tissue infection which infect the brain and muscle tissues. However the Taenia saginata can cause taeniasis, which is an infection. Taeniasis causes weight loss, pain and blockages in the intestines which can potentially become life-threatening.[14]

Diagnosis

The basic diagnosis is done from a stool sample. Feces are examined to find parasite eggs. The eggs look like other eggs from the family Taeniidae, so it is only possible to identify the eggs to the family, not to the species level. Since it is difficult to diagnose using eggs alone, looking at the scolex or the gravid proglottids can help identify it as Taenia saginata.[6] Proglottids sometimes trickle down the thighs of infected humans and are visible with unaided eye, so can aid with identification. Observation of scolex help distinguish between T. saginata, T. solium and T. asiatica. When the uterus is injected with India ink, its branches become visible. Counting the uterine branches enables some identification (T. saginata uteri have 12 or more branches on each side, while other species such as T. solium only have five to 10).[2]

Differentiation of the species of Taenia, such as T. solium and T. asiatica, is notoriously difficult because of their close morphological resemblance, and their eggs are more or less identical. Identification often requires histological observation of the uterine branches and PCR detection of ribosomal 5.8S gene.[15] The uteri of T. saginata stem out from the center to form 12 to 20 branches, but in contrast to its closely related Taenia species, the branches are much less in number and comparatively thicker; in addition, the ovaries are bilobed and testes are twice as many.[16]

Eosinophilia and elevated IgE levels are chief hematological findings. Also Ziehl–Neelsen stain can be used to differentiate between mature T. saginata and T. solium, in most cases T. saginata will stain while T. solium will not, but the method is not strictly reliable.[17]

Prevention

Adequate cooking at 56 °C (133 °F) for 5 minutes of beef viscera destroys cysticerci. Refrigeration, freezing at −10 °C (14 °F) for 9 days or long periods of salting is lethal to cysticerci. Inspection of beef and proper disposal of human excreta are also important measures.[10]

Treatment

Taeniasis is easily treated with praziquantel (5–10 mg/kg, single-administration) or niclosamide (adults and children over 6 years: 2 g, single-administration after a light breakfast, followed after 2 hours by a laxative; children aged 2–6 years: 1 g; children under 2 years: 500 mg).[10] Albendazole is also highly effective for treatment of cattle infection.[18] During the 1940s, the preferred treatment was oleoresin of aspidium, which would be introduced into the duodenum via a Rehfuss tube.[19]

See also

References

- 1 2 Eckert J. (2005). "Helminths". In Kayser, F.H.; Bienz, K.A.; Eckert, J.; Zinkernagel, R.M. (eds.). Medical Microbiology. Stuttgart: Thieme. pp. 560–562. ISBN 9781588902450.

- 1 2 3 Somers, Kenneth D.; Morse, Stephen A. (2010). Lange Microbiology and Infectious Diseases Flash Cards (2nd ed.). New York: Lange Medical Books/ McGraw-Hill. pp. 184–186. ISBN 9780071628792.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bogitsh, Burton J.; Carter, Clint E. (2013). Human Parasitology (4th ed.). Amsterdam: Academic Press. pp. 244–245. ISBN 9780124159150.

- 1 2 Winn Jr. Washington; Allen, Stephen; Janda, William; Koneman, Elmer; Procop, Gary; Schreckenberger, Paul; Woods, Gail (2006). Koneman's Color Atlas and Textbook of Diagnostic Microbiology (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1282–1284. ISBN 9780781730143.

- ↑ Patel, Nayan M.; Tatar, Eric L. (2007). "Unusual colonoscopy finding: Taenia saginata proglottid". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 13 (41): 5540–5541. doi:10.3748/wjg.v13.i41.5540. PMC 4171297. PMID 17907306.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Roberts, Larry S.; Janovy, John Jr. (2009). Gerald D. Schmidt & Larry S. Roberts' Foundations of parasitology (8th ed.). Boston: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-128458-5.

- 1 2 Ortega, Ynes R. (2006). Foodborne parasites. New York: Springer. pp. 207–210. ISBN 9780387311975.

- ↑ Eichenberger, Ramon M.; Thomas, Lian F.; Gabriël, Sarah; Bobić, Branco; Devleesschauwer, Brecht; Robertson, Lucy J.; Saratsis, Anastasios; Torgerson, Paul R.; Braae, Uffe C. (May 7, 2020). Dermauw, Veronique; Dorny, Pierre (eds.). "Epidemiology of Taenia saginata taeniosis/cysticercosis: a systematic review of the distribution in East, Southeast and South Asia". Parasites & Vectors. 13 (1): 234. doi:10.1186/s13071-020-04095-1. PMC 7206752. PMID 32381027.

- 1 2 Roberts, Larry S.; Janovy, JR, John; Nadler, Steve (2013). Gerald D. Schmidt & Larry S. Roberts' Foundations of Parasitology (9th ed.). New York, NY: McGrawHill. pp. 330–332. ISBN 978-0-07-352419-1.

- 1 2 3 "Taeniasis/Cysticercosis". WHO Fact sheet no. 376. World Health Organization. 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ↑ Uygur-Bayramiçli, O; Ak, O; Dabak, R; Demirhan, G; Ozer, S (2012). "Taenia saginata a rare cause of acute cholangitis: a case report". Acta Clinica Belgica. 67 (6): 436–7. doi:10.1179/ACB.67.6.2062709. PMID 23340150.

- ↑ Hendrickx, Emilie, et al. "Epidemiology of Taenia Saginata Taeniosis/Cysticercosis: A Systematic Review of the Distribution in West and Central Africa." Parasites & Vectors, vol. 12, no. 1, 2019, doi:10.1186/s13071-019-3584-7.

- ↑ "Taeniasis/Cysticercosis." World Health Organization, World Health Organization, www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/taeniasis-cysticercosis.

- ↑ Mehlhorn, Heinz (2016). Encyclopedia of parasitology (Fourth ed.). Berlin, Germany: Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 184–186. ISBN 978-3662439777.

- ↑ González LM, Montero E, Harrison LJ, Parkhouse RM, Garate T (2000). "Differential diagnosis of Taenia saginata and Taenia solium infection by PCR". J Clin Microbiol. 38 (2): 737–744. doi:10.1128/JCM.38.2.737-744.2000. PMC 86191. PMID 10655377.

- ↑ Zarlenga DS. (1991). "The differentiation of a newly described Asian taeniid from Taenia saginata using enzymatically amplified non-transcribed ribosomal DNA repeat sequences". Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 22 (suppl): 251–255. PMID 1822899.

- ↑ Juan A. Jimenez; Silvia Rodriguez; Luz M. Moyano; Yesenia Castillo; Héctor H. García (2010). "Differentiating Taenia eggs found in human stools - Does Ziehl Neelsen staining help?". Tropical Medicine & International Health. 15 (9): 1077–1081. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02579.x. PMC 3428859. PMID 20579318.

- ↑ Lopes, Welber Daniel Zanetti; Cruz Breno Cayeiro; Soares, Vando Edésio; Nunes, Jorge Luis N.; Teixeira, Weslen Fabricio Pires; Maciel, Willian Giquelin; Buzzulini, Carolina; Pereira, João Carlos Melo; Felippelli, Gustavo; Soccol, Vanette Thomaz; de Oliveira, Gilson Pereira; da Costa, Alvimar José (2014). "Historic of therapeutic efficacy of albendazol sulphoxide administered in different routes, dosages and treatment schemes, against Taenia saginata cysticercus in cattle experimentally infected". Experimental Parasitology. 137 (1): 14–20. doi:10.1016/j.exppara.2013.11.007. PMID 24309372.

- ↑ "Clinical Aspects and Treatment of the More Common Intestinal Parasites of Man (TB-33)". Veterans Administration Technical Bulletin 1946 & 1947. 10: 1–14. 1948.