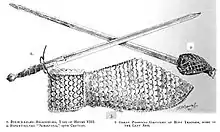

The basket-hilted sword is a sword type of the early modern era characterised by a basket-shaped guard that protects the hand. The basket hilt is a development of the quillons added to swords' crossguards since the Late Middle Ages. In modern times, this variety of sword is also sometimes referred to as the broadsword.[1][2]

The basket-hilted sword was generally in use as a military sword. True broadsword possesses a double-edged blade, while similar wide-bladed swords with a single sharpened edge and a thickened back are called backswords. Various forms of basket-hilt were mounted on both broadsword and backsword blades.[3]

One of the weapon types in the modern German dueling sport of Mensur ("academic fencing") is the basket-hilted Korbschläger.[4]

Morphology

The basket-hilted sword is a development of the 16th century, rising to popularity in the 17th century and remaining in widespread use throughout the 18th century, used especially by heavy cavalry up to the Napoleonic era.

One of the earliest basket-hilted swords was recovered from the wreck of the Mary Rose, an English warship lost in 1545. Before the find, the earliest positive dating had been two swords from around the time of the English Civil War.[5] At first the wire guard was a simple design but as time passed it became increasingly sculpted and ornate.[6]

The basket-hilted sword was a cut and thrust sword which found the most use in a military context, contrasting with the rapier, the similarly heavy, thrust-oriented sword most often worn with civilian dress which evolved from the espada ropera or spada da lato type during the same period. The term "broadsword" was used in the 17th and 18th centuries, referring to double-edged basket-hilted swords. The term was introduced to distinguish these cut and thrust swords from the smaller and narrower smallsword.

By the 17th century there were regional variations of basket-hilts: the Walloon hilt, the Sinclair hilt, schiavona, mortuary sword, Scottish broadsword, and some types of eastern European pallasches.[7][8][9] The mortuary and claybeg variants were commonly used in the British isles, whether domestically produced or acquired through trade with Italy and Germany. They also influenced the 18th-century cavalry sabre.[10]

During the 18th century, the fashion of duelling in Europe focused on the lighter small sword, and fencing with the broadsword came to be seen as a speciality of Scotland. A number of fencing manuals teaching fencing with the Scottish broadsword were published throughout the 18th century.

Descendants of the basket-hilted sword, albeit in the form of backswords with reduced "half" or "three-quarter" baskets, remained in use in cavalry during the Napoleonic era and throughout the 19th century, specifically as the 1796 Heavy Cavalry Sword, the Gothic Hilted British Infantry Swords of the 1820s to 1890s, the 1897 Pattern British Infantry Officer's Sword and as the Pattern 1908 and 1912 cavalry swords down to the eve of World War I. One of the last active use of the scottish broadsword in war was in World War II by Major Jack Churchill.

Subtypes

Schiavona

The Schiavona was a Renaissance sword that became popular in Italy during the 16th and 17th centuries.[11] Stemming from the 16th-century sword of the Balkan mercenaries who formed the bodyguard of the Doge of Venice, the name came from the fact that the guard consisted largely of the Schiavoni, Istrian and Dalmatian Slavs.[9] It was widely recognizable for its "cat's-head pommel" and distinctive handguard made up of many leaf-shaped brass or iron bars that were attached to the cross-bar and knucklebow rather than the pommel.[9]

Classified as a true broadsword, this war sword had a wider blade than its contemporary civilian rapiers. While a rapier is primarily a thrusting sword, a schiavona is a cut and thrust sword that has extra weight for greater penetration. It was basket-hilted (often with an imbedded quillon for an upper guard) and its blade was double edged. A surviving blade measures 93.2 cm (36.7 in) × 3.4 cm (1.3 in) × 0.45 cm (0.18 in) and bears two fullers or grooves running about 1/4 the length of the blade. Weighing in at around 1.1 kg (2.4 lb), this blade was useful for both cut and thrust.[12]

The schiavona became popular among the armies of those who traded with Italy during the 17th century and was the weapon of choice for many heavy cavalry.[13] It was popular among mercenary soldiers and wealthy civilians alike; examples decorated with gilding and precious stones were imported by the upper classes to be worn as a combination of fashion accessory and defensive weapon.[14]

Mortuary sword

A similar weapon was the cut-and-thrust mortuary sword which was used after 1625 by cavalry during the English Civil War. This (usually) two-edged sword sported a half-basket hilt with a straight blade some 90–105 cm long. These hilts were often of very intricate sculpting and design.

After the execution of King Charles I (1649), basket-hilted swords were made which depicted the face or death mask of the "martyred" king on the hilt. These swords came to be known as "mortuary swords", and the term has been extended to refer to the entire type of Civil War–era broadswords by some 20th-century authors.[15] Other scholars dispute that the faces etched on the hilt are Charles I. There are examples used on both sides of the conflict and the face imagery appeared before Charles I died.[16]

One possible explanation for the "Mortuary" name is that in the decades after the English Civil Wars, the arms of war heroes were donated to churches. The Churches painted the swords black and used them in funeral displays until the 19th century when many were sold into the antique market.[16]

This sword was Oliver Cromwell's weapon of choice; the one he owned is now held by the Royal Armories, and displayed at the Tower of London.[17] Two Mortuary swords also reputed to belong to Cromwell are at the Cromwell Museum and another at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[18][19] Mortuary swords remained in use until around 1670.[10]

Scottish broadsword

A common weapon among the clansmen during the Jacobite rebellions of the late 17th and early 18th centuries was the Scottish basket hilted broadsword, commonly known as claidheamh mor or claymore meaning "great sword" in Gaelic. Some authors suggest that claybeg should be used instead, from a purported Gaelic claidheamh beag "small sword". This does not parallel Scottish Gaelic usage. According to the Gaelic Dictionary by R. A. Armstrong (1825), claidheamh mór "big/great sword" translates to "broadsword", and claidheamh dà làimh to "two-handed sword", while claidheamh beag "small sword" is given as a translation of "Bilbo".[20]

Sinclair Hilt

The "Sinclair Hilt" is the name given by Victorian antiquarians, in the late 19th century, to Scandinavian swords that "bear a certain resemblance" to swords used in the Scottish Highlands in the 17th and 18th centuries. They named the sword for George Sinclair, a Scottish mercenary who died in the battle of Kringen in Norway.(d. 1612).[21]

Walloon sword

The so-called walloon sword (épée wallone)[22] or haudegen (hewing sword) was common in Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands and Scandinavia in the Thirty Years' War and Baroque era. The historian and sword typologist Ewart Oakeshott proposed an English origin for this type of sword, with subsequent development in the Netherlands and Germany.[23] Basket-hilted rapiers and sword-rapiers, characterised by pierced shell-guards, made during the same period are known as Pappenheimer rapiers.

The Walloon sword was favoured by both the military and civilian gentry.[24] A distinctive feature of the Walloon sword is the presence of a thumb-ring, and it was therefore not ambidextrous. The most common hilt type featured a double shell guard and half-basket, though examples exist with hand protection ranging from a shell and single knuckle-bow to a full basket.[25] The hilt may have influenced the design of 18th century continental hunting hangers.

Following their campaign in the Netherlands in 1672 (when many of these German-made swords were captured from the Dutch), the French began producing this weapon as their first regulation sword.[26] Weapons of this design were also issued to the Swedish army from the time of Gustavus Adolphus until as late as the 1850s.[27]

Venetian schiavona, type 2a, of the late 17th century

Venetian schiavona, type 2a, of the late 17th century British Pattern 1788 Heavy Cavalry Sword

British Pattern 1788 Heavy Cavalry Sword A Scottish broadsword of the claidheamh cuil or "back-sword" type

A Scottish broadsword of the claidheamh cuil or "back-sword" type Swiss-made Walloon sword

Swiss-made Walloon sword George Sinclair's forces land in Norway, 1612. The soldier in the center is armed with a Sinclair hilt broadsword and wears a comb morion.

George Sinclair's forces land in Norway, 1612. The soldier in the center is armed with a Sinclair hilt broadsword and wears a comb morion. "The Advantage of Shifting the Leg", plate from Henry Angelo & Son's Hungarian and Highland Broadsword (1799).

"The Advantage of Shifting the Leg", plate from Henry Angelo & Son's Hungarian and Highland Broadsword (1799).

See also

- Backsword

- Claymore

- Elizabethan fencing

- Historical fencing in Scotland

- Pata (sword), similar guarding concept

- Swiss arms and armour

Notes

- ↑ "Broadswords". thearma.org. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ↑ Oakeshott, Ewart (2012) [1980]. European Weapons and Armour: From the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 156, 173, 175. ISBN 978-1-84383-720-6.

- ↑ Martyn, pp. 6, 29

- ↑ see Korbschläger article in German Wikipedia.

- ↑ BBC News, "Sword from Mary Rose on display", 26 July 2007. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ↑ Oakeshott, Ewart, The Sword in the Age of Chivalry (1964).

- ↑ Henry Charles Howard Suffolk and Berkshire (Earl of), Hedley Peek, Frederick George Aflalo, The Encyclopaedia of Sport & Games, Volume 1 (1911), pp. 349–355.

- ↑ "Forms of European Edged Weaponry". MyArmoury.com.

- 1 2 3 Robinson, Nathan. "The Schiavona and its influences." MyArmoury.com. Retrieved on 4 December 2008.

- 1 2 Goodwin, William. "Mortuary Hilt Sword." MyArmoury.com. Retrieved on 4 December 2008.

- ↑ "Bink, J, A 17th century Masterpiece (Dec 8, 2008)". Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- ↑ "Schiavona - Historical Reference - Currently Unavailable". Reliks Swords, Knives and Collectibles.

- ↑ "schiavona - Everything2.com". everything2.com.

- ↑ Ross Dean, Antique andReplica Schiavonas (Dec 8 2008)

- ↑ "Many of these baskets were decorated with embossed heads‥taken to represent the executed King Charles I, and for this reason they are often described as mortuary swords." Frederick Wilkinson, Swords & daggers (1967), i.24. See also Cromwellian Scotland - Mortuary Sword

- 1 2 Mowbray, Stuart (1 May 2013). British Military Swords, Volume I: 1600 to 1660 The English Civil Wars and the Birth of the British Standing Army. Andrew Mowbray Publishers, Inc. pp. 178–180. ISBN 978-1931464611.

- ↑ "Sword - Mortuary sword Reputed to have been Cromwell's". Royal Armouries collections. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ↑ "Arms and Armour | Key Collections | Key Collections | Cromwell". www.cromwellmuseum.org. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ↑ "Broadsword of Oliver Cromwell". philamuseum.org. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ↑ A Gaelic Dictionary, p. 120. see also Wagner, Paul; Christopher Thompson (2005). "The words "claymore" and "broadsword"". SPADA. Highland Village, Texas: The Chivalry Bookshelf. 2: 111–117.. Dwelly's Illustrated Gaelic to English Dictionary (Gairm Publications, Glasgow, 1988, p. 202); Culloden – The Swords and the Sorrows (The National Trust for Scotland, Glasgow, 1996).

- ↑ Oakeshott, E. (2012) [1980]. European Weapons and Armour: From the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. pp. 172–173. ISBN 978-1-84383-720-6.

- ↑ Vladimir Brnardic, Darko Pavlovic, Imperial Armies of the Thirty Years' War (2): Cavalry, Osprey Publishing, 2010, ISBN 978-1-84603-997-3, p.20 Archived 21 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Oakeshott, p. 172

- ↑ Grandy, Bill. "Pappenheimer Sword". myArmoury.com.

- ↑ "European XVIIe Century Cavalry Walloon Broadsword". Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ↑ Robinson, Nathan. "Walloon Swords". myArmoury.com.

- ↑ "Armemuseum - Varjor". Archived from the original on 11 May 2009. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

References

- C. Martyn, The British Cavalry Sword from 1800, Pen and Sword Books, Barnsley (2004).

- R. E. Oakeshott, European weapons and armour: From the Renaissance to the industrial revolution (1980).

External links

- Scottish basket-hilted swords in the National Museum of Scotland, Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, and the Trades House of Glasgow.

- The basket-hilted sword. Description and photos (interestingswords.com)

- Schiavona – Venetian basket-hilted sword (interestingswords.com)