State of Baroda | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1721–1949 | |||||||||

Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||

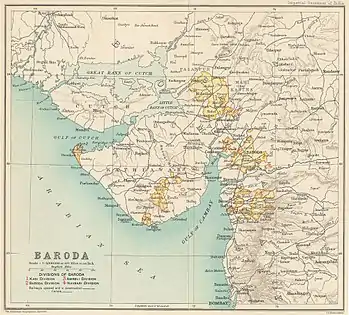

Baroda State in 1901. | |||||||||

| Status | State Within the Maratha Confederacy (1721–1818) Protectorate of the East India Company (1818–1857) Princely State of the British Raj (1857–1947) State of the Dominion of India (1947–1949) | ||||||||

| Capital | Baroda (Vadodara) | ||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism (State) Islam Jainism Christianity Zoroastrianism | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Baroda | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Raja | |||||||||

• 1721 – 1732 (first) | Pilaji Rao Gaekwad | ||||||||

• 1939 – 1949 (last)[lower-alpha 1] | Pratap Singh Rao Gaekwad | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1721 | ||||||||

| 1949 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Gujarat, Republic of India (after independence of India in 1947) | ||||||||

Baroda State was a princely state in present-day Gujarat, ruled by the Gaekwad dynasty of the Maratha Confederacy from its formation in 1721 until its accession to the newly formed Dominion of India in 1949. With the city of Baroda (Vadodara) as its capital, during the British Raj its relations with the British were managed by the Baroda Residency. The revenue of the state in 1901 was Rs. 13,661,000.[1] Baroda formally acceded to the Dominion of India, on 1 May 1949, before which an interim government was formed in the state.[2]

History

Early history

Baroda derives its native name Vadodara from the Sanskrit word vatodara, meaning 'in the heart of the Banyan (Vata) tree. It also has another name, Virakshetra or Virawati (land of warriors), mentioned alongside Vadodara by the 17th century Gujarati poet Premanand Bhatt, native to the city. Its name has been mentioned as Brodera by early English travellers and merchants, from which its later name Baroda was derived.[3] Geographically it comprised several disjointed tracts of land, measuring over 1000 square miles, spread across the present Gujarat state; these were subdivided into four prant (states), namely Kadi, Baroda, Navsari and Amreli, which included coastal portions of the state, in the Okhamadal region near Dwarka and Kodinar near Diu.[4]

The Marathas first attacked Gujarat in 1705. By 1712, a Maratha leader Khande Rao Dabhade grew powerful in the region and when he returned to Satara in 1716, he was made the senapati (commander in chief). Thereafter during the "Battle of Balapur" in 1721, one of his officers, Damaji Gaekwad was awarded the title Shamsher Bahadur or Distinguished Swordsman. Damaji died in 1721 and was succeeded by his nephew Pilajirao.[5]

Thus the Baroda State was founded in 1721, when the Maratha general Pilaji Gaekwad conquered Songadh from the Mughals. Before this Pilajirao was appointed as general to collect revenues from Gujarat by the Peshwa, the Prime Minister of the Maratha Empire, who had taken over the region north and south of Surat from the Mughals to established the Sarkar of Surat. Songadh remained the headquarters of the "House of Gaekwad" until 1866.[6][7] After the Second Anglo-Maratha War (1803–1805), the East India Company wrested control of much of Gujarat from the Marathas. However, the Gaekwads of Baroda (Vadodara), made a separate peace with the British, entering into a subsidiary alliance which acknowledged British suzerainty and control of the state's external affairs in return for retaining internal autonomy.

Princely state

Following the death of Sir Khanderao Gaekwad (1828–1870), the popular Maharaja of Baroda, in 1870, it was expected that his brother, Malharrao (1831–1882), would succeed him. However, Malharrao had already proven himself to be of the vilest character and had been imprisoned earlier for conspiring to assassinate Khanderao. As Khanderao's widow, Maharani Jamnabai (1853–1898) was already pregnant with a posthumous child, the succession was delayed until the gender of the child could be proven. The child proved to be a daughter, and so upon her birth on 5 July 1871, Malharrao ascended the throne.

Malharrao spent money liberally, nearly emptying the Barodan state coffers (he commissioned a pair of solid gold cannon and a carpet of pearls, among other expenses) and soon reports reached the Resident of Malharrao's gross tyranny and cruelty. Malharrao further attempted to cover up his deeds by poisoning the Resident, Colonel R. Phayre C.B. with a compound of arsenic. By order of the Secretary of State for India, Lord Salisbury, Malharrao was deposed on 10 April 1875 and exiled to Madras, where he died in obscurity in 1882.[8] With the throne of Baroda now vacant, Maharani Jamnabai called on the heads of the extended branches of the dynasty to come to Baroda and present themselves and their sons in order to decide upon a successor.

Kashirao and his three sons, Anandrao (1857–1917), Gopalrao (1863–1938) and Sampatrao (1865–1934) walked to Baroda from Kavlana-a distance of some 600 kilometres - to present themselves to Jamnabai.

Eventually, Gopalrao was selected by the British Government as successor and was accordingly adopted by Maharani Jamnabai, on 27 May 1875. He was also given a new name, Sayajirao. On 16 June 1875, he ascended the throne as Sayajirao Gaekwad III, but being a minor, reigned under a Council of Regency until he came of age and was invested with full ruling powers on 28 December 1881. founding numerous institutions,

20th century

Various important state institutions were founded in the early 20th century, including the Bank of Baroda on 20 July 1908. In 1908, Sayajirao also founded the Baroda Legislative Assembly (also known as the Baroda Dhara Sabha).[9]

By the beginning of the 20th century, the relations of the British with the four largest princely states—Hyderabad, Mysore, Jammu and Kashmir, and Baroda were managed by a British Resident under the direct authority the Governor-General of India.[10] In 1911, Baroda State spanned 3,239 km2 (1,251 sq mi), and the population was 2,032,798 persons as per the 1911 census of India.[11] The state was very wealthy. The Pittsburgh Press reported in 1927 that the diamond necklace, which contained the Star of the South diamond, was a part of a royal collection worth $10,000,000 at the time, housed in the Nazarbaug Palace (built 1721) in Baroda city; another important part of the collection was a cloth embroidered with precious stones and seed pearls, made to cover the tomb of Mohammed.[12][13]

Dr. B.R.Ambedkar writes about his experience with untouchability in Baroda in the second chapter of his autobiographical book, Waiting for a Visa.[14]

In 1937, the princely states of the Baroda Residency were merged with those of the agencies adjacent to the northern part of the Bombay Presidency — Rewa Kantha Agency, Surat Agency, Nasik Agency, Kaira Agency and Thana Agency — in order to form the Baroda and Gujarat States Agency.[15] A few years before independence the process of the 'Attachment Scheme' began in order to integrate the smallest princely states, estates and thanas. Baroda State was one of the main beneficiaries of this measure by being able to add about 15,000 km2 and half a million inhabitants to the state. The merged states were Pethapur on 1 February 1940, the Katosan Thana, with Deloli, Kalsapura, Maguna, Memadpura, Rampura, Ranipura, Tejpura, Varsora, the Palaj Taluka and both Ijpura States between June and July 1940. These were followed on 10 July 1943 by the states of Ambliara, Ghorasar, Ilol, Katosan, Khadal, Patdi, Punadra, Ranasan, Wasoda and Wao[16] Also many small Talukas of the region were merged. On 24 July 1943 Sachodar State and a few small places that had no own jurisdiction were annexed. By December of the same year the small states of Bajana, Bhilka, Malpur, Mansa and Vadia followed suit.[17]

Finally on 5 November 1944 the Baroda and Gujarat States Agency was merged with the Western India States Agency (WISA) to form the larger Baroda, Western India and Gujarat States Agency.

After the independence of India, which initially did not include Baroda or many other princely states, an interim government under Prime Minister Dr. Jivraj Narayan Mehta, son-in-law of Manubhai Mehta, then Dewan of Baroda state, was inaugurated in the State, on 4 September 1948, by the then Maharaja at a special Durbar in the Laxmi Vilas Palace, Baroda.[18] Finally on 1 May 1949, Baroda State, the third largest state at the time of British India, formally acceded to the Dominion of India,[2][19] Initially, Baroda merged with the Bombay state, and then, on 1 May 1960, when the two new states of Gujarat and Maharashtra were formed, it became part of Gujarat, with Dr. Jivraj Narayan Mehta becoming the first Chief Minister of Gujarat.

Koli revolt

The Koli rebellion was led by two brothers Nathaji Patel and Yamaji Patel, chiefs of Chandap Taluq. During the great Indian Rebellion of 1857, the Kolis of Chandap under Nathaji and Yamaji planning for revolt and Gaekwad of Baroda received that news. So Gaekwad stationed his cavalry at Chandap to control the rebels. But cavalry of Gaekwad was killed and thrown out by Kolis of Chandap. After that Kolis went into Taranga hills and continued their rebellion for few months. In the end of October 1857, the combined forces of British, Idar State and Baroda attacked Kolis and burnt the Chandap village.[20]

In north-west Gujarat, around the southern tip of the Aravali, a number of Koli Talukdars revolted against the triumvirate of the British, Gaekwad and Raja of Idar. Together, these three forces burnt down two Koli villages towards the end of 1857. The Koli chieftains collected an army of 2000 Koli- and Bhil soldiers and attacked Gaekwadi villages near present day Gandhinagar. Adopting guerrilla tactics, they continued their resistance till the end of 1858. While Koli chiefs fought around the river Sabarmati. The Kolis paid a huge price for their resistance to British and Baroda. They were not only defeated in battle and punished for having dared to resist but, in the aftermath, kolis were marginalized by the rest of society as outlaws. Being arms-bearing community, they too were disarmed in early 1858 and also forced to practise agriculture.[21]

Baroda State Railway

The state owned the Gaekwar's Baroda State Railway (GBSR), which started in 1862 as the first narrow-gauge in India. It consisted of 8 miles (13 km) of narrow gauge track from Dabhoi to Miyagam.[22] The railway network extended to Goyagate, Chandod, Bodeli and Samalaya Jn with Dabhoi as its focal point. After independence in 1949 this railway merged with the Bombay, Baroda and Central India Railway. The lines are under conversion to broad gauge currently.[23]

Baroda State Navy

In late 18th century, the Baroda state established a Naval set up at Billimora, a port about 40 miles south of Surat, known as Bunder Billimora Suba Armor. Here a fleet of 50 vessels was stationed, which included mostly sails, cargo vessels for trading and military vessels to secure the sea from Portuguese, Dutch and French.[6]

When political alignments changed, after the Second Anglo-Maratha war, a joint expedition of British and Barodan state troops under Colonel Walker, then resident of Baroda, approached Kathiawad in 1808, and eventually obtained bonds from the chiefs of Okha-mandal and from the maritime states of Kathiawad renouncing piracy. Then in 1813, the Barodan government acquired the parganah of Kodinar (in present Junagadh district), where at port of Velan a small fleet of four frigates with 12-pounder guns on each for the protection of the trade between Bombay and Sindh was established. These four armed vessels were named Anandprasad, Sarsuba, Anamat Vart and Anne Maria, which was purchased from the Shah of Iran, and was known as 'Shah Kai Khusru' until then.[6]

Gaekwad Maharajas of Baroda

- Pilaji Rao Gaekwad (1721–1732)

- Damaji Rao Gaekwad (1732–1768)

- Sayaji Rao I Gaekwad (1768–1778)

- Fateh Singh Rao Gaekwad (1778–1789)

- Manaji Rao Gaekwad (1789–1793)

- Govind Rao Gaekwad (1793–1800)

- Anand Rao Gaekwad (1800–1818)

- Sayaji Rao Gaekwad II (1818–1847)

- Ganpat Rao Gaekwad (1847–1856)

- Khande Rao Gaekwad (1856–1870)

- Malhar Rao Gaekwad (1870–1875)

- Sayajirao Gaekwad III (1875–1939)

- Pratap Singh Rao Gaekwad (1939–1951); ruled from 1939 to 1947, serving as nominal ruler to his death in 1951

Titular Maharajas

- Fatehsinghrao Gaekwad II (1951–1988) titular Maharaj of Baroda until 1971 when All the royal titles in India were officially abolished in 1971 under the Twenty-sixth Amendment of the Constitution of India by Indira Gandhi's government.

Later heads of family

- Ranjitsinh Pratapsinh Gaekwad (1988–2012; pretender)

- Samarjitsinh Gaekwad (2012–present; pretender)

Present line of succession to the Baroda throne

The Gaekwad dynasty follows the standard of male primogeniture in matters of succession. The present line of succession is as follows:

- Shrimant Prince (Maharajkumar) Sangramsinhrao Gaekwad, the Heir Presumptive (6 August 1941–). Uncle of the present Maharaja.

- Shrimant Maharajkumar Pratapsinhrao Sangramsinhrao Gaekwad (26 August 1971–). Only son of Sangramsinhrao Gaekwad.

- Shrimant Rajkumar Sayajirao Khanderao Gaekwad (6 April 1947–). Great-grandson of Sayajirao Gaekwad III by the Maharaja's younger son Shivajirao (1890–1919) and through Shivajirao's son Khanderao (1916–1991). Has two daughters.

- Shrimant Rajkumar Anandrao Khanderao Gaekwad (28 September 1948–). Younger brother of Sayajirao Khanderao Gaekwad. Has two sons.

- Shrimant Shivajirao Anandrao Gaekwar (21 September 1983–). Elder son of Anandrao Khanderao Gaekwad.

- Shrimant Udaysingh Anandrao Gaekwar (3 December 1990–). Younger son of Anandrao Khanderao Gaekwad.

- Shrimant Kr Jeetendrasinh Gautamsinhrao Gaekwad (4 Nov 1960–), son of Late Professor Shrimant Gautamsinhrao Bhadrasinhrao Gaekwad (1936–2006). Great Grandnephew of Maharaja Sir Sayajirao III. Great Grandson of the Maharaja's late elder brother 'Senapati' Anandrao, Himmat Bahadur, CIE (1857–1917). Grandson of Anandrao's son 'Rajyakarya Dhurandhar' 'Dewan' 'Barrister' Bhadrasinhrao Anandrao Gaekwad, CIE (1896–1946).

- Shrimant Satyajitsinhrao Duleepsinhrao Gaekwad (3 March 1962–). Great-grandnephew of Sayajirao Gaekwad III through the Maharaja's elder brother Anandrao, Himmat Bahadur, CIE (1857–1917), through Anandrao's son Chandrasinhrao (born 1894–?) and through his grandson Duleepsinhrao (b. c. 1920–?)

- Shrimant Yudeepsinhrao Satyajitsinhrao Gaekwad (2001–). Son of Satyajitsinhrao.

Diwans of Baroda

List of Diwans of Baroda:[24]

- Bhau Shinde – (17 November 1867 – 24 November 1869)

- Nimbaji Rao Dhole (acting) – (25 November 1869 – November 1870)

- Hariba Dada – (November 1870 – March 1871)

- Gopal Rav Mairal – (22 March 1871 – 1872)

- Balwant Rao Bhicaji Rahurakar – (1872–72) (4 months)

- Balvantrav Khanvelkar – (November 1872 – March 1873)

- Shivaji Rao Khanvelkar – (5 March 1873 – 4 August 1874)

- Dadabhai Naoroji – ( 4 August 1874 – 7 January 1875)

- Rajah Sir T. Madhava Rao – (16 May 1875 – 28 September 1882)

- Khan Bahadur Kazi Shahabuddin – (29 September 1882 – 31 July 1886)

- Diwan Bahadur Lakshman Jagannath Vaidya – (1 August 1886 – 30 May 1890)

- Diwan Bahadur Manibhai Jashbhai – (31 May 1890 – 21 November 1895)

- Diwan Bahadur S. Srinivasa Raghavaiyangar – (15 July 1895 – 2 July 1901)

- Diwan Bahadur R. V. Dhamnaskar – (3 October 1901 – 30 June 1904)

- Kersaspji Rustamji Dadachanji – (1 July 1904 – 28 February 1909)

- Romesh Chunder Dutt, I.C.S – (1 June 1909 – 30 November 1909)

- Rahim Suleman Theba, I.C.S – (1 December 1909 – 3 January 1912)

- Behari Lal Gupta, I.C.S – (4 January 1912 – 16 March 1914)

- V. P. Madhava Rao – (17 March 1914 – 7 May 1916)

- Manubhai Nandshankar Mehta – (8 May 1916 – 1927)

- V. T. Krishnamachari – (1927–1944)

- Bhadrasinh Anandrao Gaekwar – (1944–1945)

- Sir Brojendra Lal Mitter – (1945–1947)

- Sakharam Amrit Sudhalkar – (October 1947 – June 1948)

- Jivraj Narayan Mehta – (1 June 1948 – 1 May 1949)

Historiography

In 2007, Gujarat State Department of Archives started digitising 600,000 files, including Baroda state registers, prints, maps, abhinandan patra or maan patra (felicitation letters) offered to the erstwhile King by different provincial states and organisation, aagna patrika (gazette), huzur orders, and volumes of letters exchanged and agreements of the princely state with other provincial states and the British Raj, currently housed at the 'Southern Circle Record Office' at Vadodara, where a permanent exhibition had also been set up.[25]

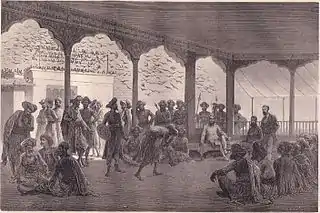

The Gaekwar in his palace |

Procession in 1872 |

Baroda king on the Great Sowari royal procession |

See also

Further reading

- Foote, Robert Bruce (1898). The geology of Baroda State. Addison.

- Mukerjea, Satyavrata. Baroda State. Government Printing, 1921.

- Gadre, A. S. (2007). Important Inscriptions from the Baroda State – (Volume 1). READ BOOKS. ISBN 978-1-4067-1136-3.

- Gupte, Balkrishna Atmaram (1922). Selections from the Historical records of the Hereditary minister of Baroda, consisting of letters from Bombay, Baroda, Poona and Satara governments. University of Calcutta.

- F. A. H. Elliot. The Rulers of Baroda. Baroda State Press 1934. ASIN B0006C35QS.

- Gense, James (1939). The Gaikwads of Baroda. D.B. Taraporevala Sons & Co 1942. ASIN B0007K1PL6.

- Kothekara, Santa. The Gaikwads of Baroda and the East India Company, 1770–1820. Nagpur University. ASIN B0006D2LAI.

- Gaekwad, Fatesinghrao * Biography of Maharaja Sayajirao III by Daji Nagesh Apte (1989). Sayajirao of Baroda: The Prince and the Man. Popular Prakashan. ISBN 978-0-86132-214-5.

- Gaekwar, Sayaji Rao. Speeches and addresses of Sayaji Rao III, Maharaja Gaekwar of Baroda. H. Milford 1933. ASIN B000855T0I.

- Rice, Stanley (1931). Life of Sayaji Rao III, Maharaja of Baroda. Oxford university press 1931. ASIN B00085DDFG.

- Clair, Edward (1911). A Year with the Gaekwar of Baroda. D. Estes & co 1911. ASIN B0008BLVV8.

- MacLeod, John (1999). Sovereignty, Power, Control: Politics in the State of Western India, 1916–1947. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-11343-6.

- Kamerkar, Mani. British Paramountcy: British-Baroda Relations, 1818-1848. Popular Prakashan. ASIN B000JLZE6A.

- Kooiman, Dick (2002). Communalism and Indian Princely States: Travancore, Baroda and Hyderabad in the 1930s. Manohar Pubns. ISBN 978-81-7304-421-2.

- Desai, Govindbhai. Forty Years in Baroda: Being Reminiscences of Forty Years' Service in the Baroda State. Pustakalaya Sahayak Sahakari Mandal 1929. ASIN B0006E18R4.

- Maharaja of Baroda (1980). The Palaces of India. Viking Pr. ISBN 978-0-00-211678-7.

- Doshi, Saryu (1995). The royal bequest: Art treasures of the Baroda Museum and Picture Gallery. India Book House. ISBN 978-81-7508-009-6.

- Moore, Lucy (2005). Maharanis; the extraordinary tale of four Indian queens and their journey from purdah to parliament. Viking Press. ISBN 0-670-03368-5.

Notes

- ↑ before abolition and dilusion in the Republic of India

References

- ↑ "Imperial Gazetteer of India, Volume 7, page 25". dsal.uchicago.edu. Digital South Asia Library. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- 1 2 "Rulers Farewell Message". The Indian Express. 1 May 1949.

- ↑ Gazetteer, p. 25

- ↑ Gazetteer, p. 26

- ↑ Gazetteer, p. 31, 32

- 1 2 3 "280 years ago, Baroda had its own Navy". The Times of India. 27 September 2010. Archived from the original on 3 November 2012.

- ↑ Gazetteer, 32

- ↑ "DEPOSITION OF THE GAEKWAR OF BARODA". The Times of India. 26 April 1875.

- ↑ Kalia, Ravi (2004). Gandhinagar: Building National Identity in Postcolonial India. University of South Carolina Press. p. 37. ISBN 9781570035449.

- ↑ Imperial Gazetteer of India vol. IV (1907), p. 92.

- ↑ Somerset Playne; R. V. Solomon; J. W. Bond; Arnold Wright (2006). "The State of Baroda". Indian states: a biographical, historical, and administrative survey (illustrated ed.). Asian Educational Services. p. 9. ISBN 978-81-206-1965-4.

- ↑ "Baroda City of Palace". The Pittsburgh Press. 14 August 1927.

- ↑ "Gaekwad's Star of the South diamond sold". The Times of India. 28 March 2007. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012.

- ↑ Ambedkar, Dr. Bhimrao (1991). Waiting for a Visa (PDF). Mumbai: Dept. of education, Government of Maharashtra. pp. 4071–4090. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- ↑ History of the State of Gujarat

- ↑ which had been fourth class states in the Mahi Kantha Agency.

- ↑ McLeod, John; Sovereignty, power, control: politics in the States of Western India, 1916–1947; Leiden u.a. 1999; ISBN 90-04-11343-6; p. 160

- ↑ "Gaekwar Inaugurates Responsible Government". The Indian Express. 5 September 1948.

- ↑ "Kher's Appeal to people &Service for Cooperation". The Indian Express. 2 May 1949.

- ↑ Dharaiya, Ramanlal Kakalbhai (1970). Gujarat in 1857. New Delhi, India: Gujarat University. pp. 38 – 40 – 52.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ↑ Yājñika, Acyuta; Sheth, Suchitra (2005). The Shaping of Modern Gujarat: Plurality, Hindutva, and Beyond. New Delhi, India: Penguin Books India. pp. 93–96. ISBN 978-0-14-400038-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ↑ "Indian Railways Some Fascinating Facts: First Gauge Lines". Indian Army Official website.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ Dabhoi-Bodeli broad gauge section to become operational

- ↑ R. V. Solomon; J. W. Bond (2006). Indian States: A Biographical, Historical, and Administrative Survey. Asian Educational Services. p. 24. ISBN 9788120619654.

- ↑ "Erstwhile Gaekwad state's archives being digitised". The Indian Express. 27 December 2007. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012.

Citations

- "Baroda State". Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 7. Oxford at the Clarendon Press. 1908. pp. 25–84.