The Bāburnāma (Chagatay: بابر نامہ, lit. 'History of Babur' or 'Letters of Babur'; alternatively known as Tuzk-e Babri) is the memoirs of Ẓahīr-ud-Dīn Muhammad Bābur (1483–1530), founder of the Mughal Empire and a great-great-great-grandson of Timur. It is written in the Chagatai language, known to Babur as Türki ("Turkic"), the spoken language of the Timurids. During the reign of emperor Akbar, the work was translated into Persian, the usual literary language of the Mughal court, by a Mughal courtier, Abdul Rahim Khan-i-Khanan, in AH 998 (1589–90 CE).[1]

Bābur was an educated Timurid prince and his observations and comments in his memoirs reflect an interest in nature, society, politics and economics. His vivid account of events covers not just his own life, but the history and geography of the areas he lived in as well as the people with whom he came into contact. The book covers topics as diverse as astronomy, geography, statecraft, military matters, weapons and battles, plants and animals, biographies and family chronicles, courtiers and artists, poetry, music and paintings, wine parties, historical monument tours as well as contemplations on human nature.[2]

Though Babur himself does not seem to have commissioned any illustrated versions, his grandson began as soon as he was presented with the finished Persian translation in November 1589. The first of four illustrated copies made under Akbar over the following decade or so was broken up for sale in 1913. Some 70 miniatures are dispersed among various collections, with 20 in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. The three other versions, partly copied from the first, are in the National Museum, New Delhi (almost complete, dated 1597–98), British Library (143 out of an original 183 miniatures, probably early 1590s) with a miniature over two pages in the British Museum,[3] and a copy, mostly lacking the text, with the largest portions in the State Museum of Oriental Art, Moscow (57 folios) and the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore (30 miniatures).[4] Various other collections have isolated miniatures from these versions. Later illustrated manuscripts were also made, though not on as a grand a scale.

Babur is at the centre of most scenes shown. As far is known, no contemporary images of him survive, but from whatever sources they had Akbar's artists devised a fairly consistent representation of him, "with a roundish face and droopy moustache", wearing a Central Asian style of turban and a short-sleeved coat over a robe with long sleeves.[5] Coming from a period after Akbar's workshop had developed their new style of Mughal painting, the illustrated Baburnamas show developments such as landscape views with recession, influenced by Western art seen at court.[6] Generally the scenes are less crowded than in earlier miniatures of "historical" scenes.

Akbar's manuscripts

Most images trimmed of borders

.jpg.webp) Victoria and Albert Museum: Babur and a group of men including his son, Humayun, the next emperor were encamped near Bagram and were told that a rhinoceros had been seen nearby. As Humayun had never seen one before, they rushed to find it.

Victoria and Albert Museum: Babur and a group of men including his son, Humayun, the next emperor were encamped near Bagram and were told that a rhinoceros had been seen nearby. As Humayun had never seen one before, they rushed to find it. Babur and his army emerge from the Khwaja Didar Fort, British Museum

Babur and his army emerge from the Khwaja Didar Fort, British Museum The siege of Isfarah, Baltimore

The siege of Isfarah, Baltimore.jpg.webp) Babur visits a Hindu cave complex near Bagram, Baltimore

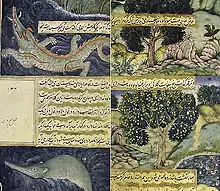

Babur visits a Hindu cave complex near Bagram, Baltimore National Museum, New Delhi, Squirrels, a Peacock and Peahen, Demoiselle Cranes and Fishes

National Museum, New Delhi, Squirrels, a Peacock and Peahen, Demoiselle Cranes and Fishes

Content

According to historian Stephen Frederic Dale, Babur's Chagatai prose is highly Persianized in its sentence structure, morphology, and vocabulary,[7] and also contains many phrases and smaller poems in Persian.

The Bāburnāma begins abruptly with these plain words:[8]

In the month of Ramadan of the year 899 [1494] and in the twelfth year of my age, I became ruler in the country of Farghana.

Bābur describes his fluctuating fortunes as a minor ruler in Central Asia – he took and lost Samarkand twice – and his move to Kabul in 1504. There is a break in all known manuscripts between 1508 and 1519. Annette Beveridge and other scholars believe that the missing part in the middle, and perhaps an account of Babur's earlier childhood, a preface and perhaps an epilogue, were written but the manuscript of those parts lost by the time of Akbar.[9] There are various points in his highly active career, and that of his son Humayun, where parts of the original manuscript might plausibly have been lost.[10]

By 1519 Bābur is established in Kabul and from there launches an invasion into north-western India. The final section of the Bāburnāma covers the years 1525 to 1529 and the establishment of the Mughal empire over what was by his death still a relatively small part of north-western India, which Bābur's descendants would expand and rule for three centuries.

The account of the decisive First Battle of Panipat in 1526 is followed by long descriptions of India, its people, fauna and flora. Various exciting incidents are recounted and illustrated: Babur jumps off his horse just in time to avoid following it into a river, and when his army has formed its boats into a circle a fish jumps into a boat to escape from a crocodile.[11]

The original Chagatai language text does not seem to have existed in many copies, and those that survive are mostly partial. The copy seen in the Mughal Library in the 1620s, and presumably used to base the Persian translation on, seems to have been lost.[12]

In this autobiography, Babur mentions a boy named 'Baburi' as a teenager, on which he was fascinated and lust soaked. This subtle feeling is expressed on pages 120 and 121 of "Baburnama", where he writes: -

(A personal episode and some verses by Babur.)

'Äyisha-sultan Begum whom my father and hers, i.e. my uncle, Sl. Aḥmad Mirzā had betrothed to me, came (this year) to Khujand¹ and I took her in the month of Sha'ban. Though I was not ill-disposed towards her, yet, this being my first marriage, out of modesty and bashfulness, I used to see her once in 10, 15, or 20 days. Later on, when even my first inclination did not last, my bashfulness increased. Then my mother Khänīm used to send me, once a month or every 40 days, with driving and driving, dunnings and worry.

In those leisurely days, I discovered in myself a strange inclination, nay! as the verse says, 'I maddened and afflicted myself' for a boy in the camp-bazar, his very name, Bāburī, fitting in. Up till then, I had had no inclination for anyone, indeed of love and desire, either by hear-say or experience, I had not heard, I had not talked. At that time I composed Persian couplets, one or two at a time; this is one of them:

May none be as I, humbled and wretched and love-sick: No beloved as thou art to me, cruel and careless.

From time to time Bāburi used to come to my presence but out of modesty and bashfulness, I could never look straight at him; how then could I make conversation (ikhtilät) and recital (hikayat)? In my joy and agitation I could not thank him (for coming); how was it possible for me to reproach him with going away? What power had I to command the duty of service to myself? One day, during that time of desire and passion when I was going with companions along a lane and suddenly met him face to face, I got into such a state of confusion that I almost went right off. To look straight at him torments and shames, I went on. A (Persian) couplet of Muhammad Salih's came into my mind.

— Baburi Andijani, in Jahiruddin Muhammad Babur, Baburnama, Page 120 FARGHANA (q. Babur's first marriage.)

Translations

It was first translated into English by John Leyden and William Erskine as Memoirs of Zehir-Ed-Din Muhammed Baber: Emperor of Hindustan,[16] later by the British orientalist scholar Annette Beveridge,[17][18] and most recently by Wheeler Thackston, who was a professor at Harvard University.[19]

Widely translated, the Bāburnāma forms part of textbooks in no fewer than 25 countries – mostly in Central, Western, and Southern Asia.

Context

The Baburnama fits into a tradition of imperial autobiographies or official court biographies, seen in various parts of the world. In South Asia these go back to the Ashokavadana and Harshacharita from ancient India, the medieval Prithviraj Raso, and were continued by the Mughals with the Akbarnama (biography), Tuzk-e-Jahangiri or Jahangir-nameh (memoirs), and Shahjahannama (genre of flattering biographies).

Akbar's ancestor Timur had been celebrated in a number of works, mostly called Zafarnama "Book of Victories", the best known of which was also produced in an illustrated copy in the 1590s by Akbar's workshop. A work purporting to be Timur's autobiography, which turned up in Jahangir's library in the 1620s, is now regarded as a fake of that period.[20]

Praise

Babur's autobiography has received widespread acclaim from modern scholars. Quoting Henry Beveridge, Stanley Lane-Poole writes:

His autobiography is one of those priceless records which are for all time, and is fit to rank with the confessions of St. Augustine and Rousseau, and the memoirs of Gibbon and Newton. In Asia it stands almost alone.[21]

Lane-Poole goes on to write:

his Memoirs are no rough soldier's chronicle of marches and countermarches...they contain the personal impressions and acute reflections of a cultivated man of the world, well read in Eastern literature, a close and curious observer, quick in perception, a discerning judge of persons, and a devoted lover of nature; one, moreover, who was well able to express his thoughts and observations in clear and vigorous language. The shrewd comments and lively impressions which break in upon the narrative give Babur's reminiscences a unique and penetrating flavour. The man's own character is so fresh and buoyant, so free from convention and cant, so rich in hope, courage, resolve, and at the same time so warm and friendly, so very human, that it conquers one's admiring sympathy.The utter frankness of self-revelation, the unconscious portraiture of all his virtues and follies, his obvious truthfulness and a fine sense of honour, give the Memoirs an authority which is equal to their charm. If ever there were a case when the testimony of a single historical document, unsupported by other evidence, should be accepted as sufficient proof, it is the case with Babur's memoirs. No reader of this prince of autobiographers can doubt his honesty or his competence as witness and chronicler.[21]

Writing about the time Babur came to India, the historian Bamber Gascoigne comments:

He was occupied at this time in linking in narrative form the jottings which he had made throughout his life as a rough diary, but he also found time for a magnificent and very detailed forty page account of his new acquisition—Hindustan. In it he explains the social structure and the caste system, the geographical outlines and the recent history; he marvels at such details as the Indian method of counting and time-keeping, the inadequacy of the lighting arrangements, the profusion of Indian craftsmen, or the want of good manners, decent trousers and cool streams; but his main emphasis is on the flora and fauna of the country, which he notes with the care of a born naturalist and describes with the eye of a painter...He separates and describes, for example, five types of parrots; he explains how plantain produces banana; and with astonishing scientific observation he announces that the rhinoceros 'resembles the horse more than any other animal' (according to modern zoologists, the order Perissodactyla has only two surviving sub-orders; one includes the rhinoceros, the other the horse). In other parts of the book too he goes into raptures over such images as the changing colors of a flock of geese on the horizon, or of some beautiful leaves on an apple tree. His progression with all its ups and downs from tiny Ferghana to Hindustan would in itself ensure him a minor place in the league of his great ancestors, Timur and Jenghiz Khan; but the sensitivity and integrity with which he recorded this personal odyssey, from buccaneer with royal blood in his veins reveling in each adventure to emperor eyeing in fascinated amazement every detail of his prize, gives him an added distinction which very few men of action achieve.[22]

Illustrations from the Manuscript of Baburnama (Memoirs of Babur)

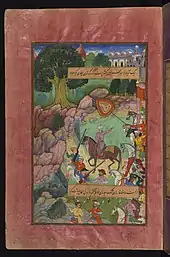

The battle of Sultan Ḥusayn Mīrzā against Sultan Masʿūd Mīrzā at Hiṣṣār

The battle of Sultan Ḥusayn Mīrzā against Sultan Masʿūd Mīrzā at Hiṣṣār.jpg.webp) Animals of Hindustan small deer and cows called gīnī, Walters

Animals of Hindustan small deer and cows called gīnī, Walters Foray to Kohat, Walters

Foray to Kohat, Walters

Notes

- ↑ "Biography of Abdur Rahim Khankhana". Archived from the original on 2006-01-17. Retrieved 2006-10-28.

- ↑ ud-Dīn Muhammad, Zahīr (2006). Babur Nama : journal of Emperor Babur. Hiro, Dilip., Beveridge, Annette Susannah. New Delhi: Penguin Books. pp. xxv. ISBN 9780144001491. OCLC 144520584.

- ↑ Losty, 39; British Museum page

- ↑ Losty, 39, with pages at 40–44

- ↑ Crill and Jariwala, 60

- ↑ Crill and Jariwala, 24–26

- ↑ Dale, Stephen Frederic (2004). The garden of the eight paradises: Bābur and the culture of Empire in Central Asia, Afghanistan and India (1483–1530). Brill. pp. 15, 150. ISBN 90-04-13707-6.

- ↑ English translation

- ↑ Beveridge, xxxii, xxxvii-xxxviii

- ↑ Beveridge, xxxv

- ↑ Losty, 44

- ↑ Beveridge, xxxix-xliii

- ↑ Khair, Tabish; Leer, Martin; Edwards, Justin D.; Ziadeh, Hanna (2005). Other Routes: 1500 Years of African and Asian Travel Writing. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-34693-3.

- ↑ "Journal of Babur". Hindustan Times. 2006-03-14. Retrieved 2021-09-11.

- ↑ Salam, Ziya Us (2014-02-15). "An emperor with foibles". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2021-09-11.

- ↑ Bābur (Emperor of Hindustān) (1826). Memoirs of Zehir-Ed-Din Muhammed Baber: emperor of Hindustan. Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

- ↑ Babur (1922). Beveridge, Annette Susannah (ed.). The Babur-nama in English (Memoirs of Babur) - Volume I. London: Luzac and Co. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ Babur (1922). Beveridge, Annette Susannah (ed.). The Babur-nama in English (Memoirs of Babur) - Volume II. London: Luzac and Co. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ Babur (2002). The Baburnama : memoirs of Babur, prince and emperor. Translated by Thackston, Wheeler. New York: Modern Library. ISBN 0375761373.

- ↑ Baburnama at Encyclopædia Iranica

- 1 2 Lane-pool, Stanley. "Babar". The Clarendon Press. pp. 12–13. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ Gascoigne, Bamber (1971). The Great Moghuls. London: Jonathan Cape; New York: Harper & Row. pp. 37–38, 42. ISBN 9780060114671.

References

- Beveridge, Annette, Introduction to her translation, The Babur-nama in English (Memoirs of Babur) at Internet Archive

- Crill, Rosemary, and Jariwala, Kapil. The Indian Portrait, 1560–1860, National Portrait Gallery, London, 2010, ISBN 9781855144095

- Losty, J. P. Roy, Malini (eds), Mughal India: Art, Culture and Empire, 2013, British Library, ISBN 0712358706, 9780712358705

Editions of the text in English

- The Babur-nama in English (Memoirs of Babur) (1922) Volume 1 by Annette Susannah Beveridge at the Internet Archive

- The Babur-nama in English (Memoirs of Babur) (1922) Volume 2 by Annette Susannah Beveridge at the Internet Archive

- The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor, Zahir-ud-din Mohammad Babur, Translated, edited and annotated by Wheeler M. Thackston. 2002 Modern Library Classics Edition, New York. ISBN 0-375-76137-3

- Babur Nama: Journal of Emperor Babur, Zahir Uddin Muhammad Babur, Translated from Chagatai Turkic by Annette Susannah Beveridge. Abridged (1/3 of the original), edited and introduced by Dilip Hiro. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-400149-1; ISBN 0-14-400149-7.