| Baboquivari Peak Wilderness | |

|---|---|

View of the east face of Baboquivari Peak | |

| |

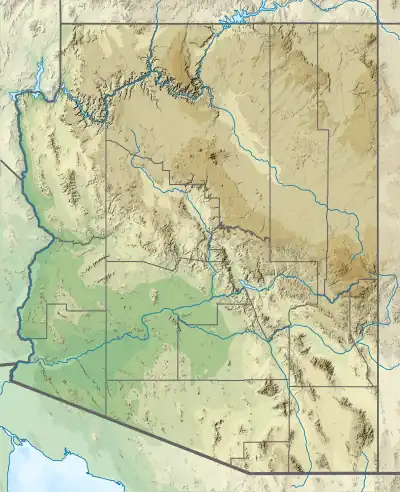

| Location | Pima County, Arizona, U.S. |

| Nearest city | Tucson, Arizona |

| Coordinates | 31°47′29″N 111°34′32″W / 31.7914724°N 111.5756642°W[1] |

| Area | 2,065 acres (836 ha) |

| Designated | 1990 |

| Governing body | Bureau of Land Management |

The Baboquivari Peak Wilderness or La Bestia is a 2,065-acre (8 km2) wilderness area in the U.S. state of Arizona. It is located in the Baboquivari Mountains 50 miles (80 km) southwest of Tucson, Arizona.[2] It is administered by the Bureau of Land Management. The United States Congress designated the Baboquivari Peak Wilderness in 1990. It is the smallest such designated wilderness in the state of Arizona. Today, the 2,900,000-acre (12,000 km2) Tohono O'odham Nation (second largest reservation in the United States) lies to the west. Baboquivari Peak's elevation is 7,730 feet (2,356 m). It is a popular site for many climbers, tourists and other visitors to Arizona and can be seen in the distance from the Kitt Peak National Observatory. The mountain was well known as a place to find flint for arrow points. BA BO QUAY VI RA, is translated as the place for the mother lode of flint (America, Land of the Rising Sun—Don Smithana).

Baboquivari Peak is a technical summit, meaning that it is only accessible by technical (class 5) rock climbing according to the Yosemite Decimal System. The wilderness is reported to have some of the best backcountry rock climbing in Arizona. It can be visited any time of the year; however, outside visitors who are not members of the Tohono O'odham nation, must first procure a permit to be on the reservation. Also, summer afternoons are usually too hot for hiking, and winter can bring an occasional snow shower to the peak's highest elevations. Sightings of jaguars have been recorded in the Baboquivaris during the last decades.[3]

Cultural significance

Baboquivari Peak is the most sacred place to the Tohono O'odham people. It is the center of the Tohono O'odham cosmology and the home of the creator, I'itoi. According to tribal legend, he resides in a cave below the base of the mountain.[4]

This mountain is regarded by the O'odham nation as the navel of the world – a place where the earth opened and the people emerged after the great flood. Baboquivari Peak is also sometimes referred to as I'Itoi Mountain. In the native O'odham language, it is referred to as Waw Kiwulik. Waw refers to a cliff or rocky outcropping (as opposed to the more general do'ag "mountain"). Kiwulik (sometimes spelled kiwulk or giwulk) is a stative verb meaning "(be) narrow, (be) constricted".[5] The O'odham people believe that he watches over their people to this day.[4][6]

Baboquivari Peak was mentioned in the journals of Jesuit missionary Padre Kino, who made many expeditions into this region of the Sonoran Desert, beginning in 1699, establishing Spanish Missions in the area.[7][8]

Legend surrounding Baboquivari

According to O'odham nation legend at the beginning of the Spanish conquest of what is present day Arizona, a certain Spanish officer and his men tried to dig their way into Baboquivari. Suddenly, the ground under them opened and Baboquivari swallowed them. This legend has similarities to Francisco Vásquez de Coronado search for the Seven Cities of Cibola and a place called Quivira, where, he was told, he could get his hands on unlimited quantities of gold.[9]

Climbing history

Baboquivari peak is a technical summit, meaning that it is only accessible by technical (class 5) rock climbing according to the Yosemite Decimal System. The easiest route to the peak is the Standard Route, rated at 5.4.

Dr. Robert Humphrey Forbes (1867–1968), a professor of agriculture at the University of Arizona, and Sr. Lorenzo Montoya made the first recorded ascent of the peak on July 12, 1898, after five attempts. Their approach, from the east face of the peak, is now known as the Forbes route or Forbes-Montoya route.[10] In the 1930s, the Arizona Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) installed wood-and-metal stairs on the west face along a long slabby feature called the Great Ramp, which merges with the original Forbes-Montoya route; a wood-and-metal ladder on what is now called the Ladder Pitch, and an observation tower at the summit. These structures were intended to make it easier to reach and enjoy the summit. They aged and were eventually dismantled, but wood and metal remnants remain along this route, now known to climbers as the Standard Route or the western approach to the Forbes Route.

Natural features

There are a considerable number of topographic features within the Baboquivari Mountains, one of the most notable being Fresnal Canyon. Numerous flora and fauna species are found in the Baboquivari Peak Wilderness; among these is the desert tree Bursera fagaroides.[11]

See also

References

- ↑ "Baboquivari Peak Wilderness". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ↑ "Baboquivari Peak Wilderness Area". Bureau of Land Management. Archived from the original on June 17, 2015. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ Mccain, Emil B.; Childs, Jack L. (2008). "Evidence of resident jaguars (Panthera onca) in the Southwestern United States and the implications for conservation" (PDF). Journal of Mammalogy. 89 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1644/07-mamm-f-268.1. S2CID 58923352. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- 1 2 "Baboquivari Mountain Petroglyphs, AZ (Tohono O'odham)". The Pluralism Project. 2004. Archived from the original on September 24, 2014. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ Saxton, Dean; Saxton, Lucille; Enos, Susie (1983). Tohono O'odham/Pima to English, English to Tohono O'odham/Pima Dictionary. Tucson, AZ: The University of Arizona Press. ISBN 9780816519422.

- ↑ "Kitt Peak National Observatory". National Optical Astronomy Observatory. Archived from the original on February 4, 2015. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Baboquivari Peak Wilderness and Coyote Mountain Wilderness" (PDF). Bureau of Land Management. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ Green, Stewart M. (1999). Rock Climbing Arizona. FalconGuides. p. 89. ISBN 9781560448136.

- ↑ Matlock, Gene (2000). India Once Rule the Americas!. iUniverse. p. 31. ISBN 978-0595134687.

- ↑ Backcountry Rockclimbing in Southern Arizona, Second Edition (1997), p. 131, by Bob Kerry. ISBN 0964113716. (353 pages)

- ↑ Hogan, C. Michael (October 11, 2009). "Elephant Tree Bursera microphylla". iGoTerra. Archived from the original on December 29, 2014. Retrieved January 17, 2015.