BP Pedestrian Bridge | |

|---|---|

The BP Bridge viewed from The Buckingham in Lakeshore East (June 12, 2008) | |

| Coordinates | 41°52′58″N 87°37′14″W / 41.8828°N 87.6206°W |

| Carries | Pedestrians |

| Crosses | Columbus Drive |

| Locale | Chicago (Cook County, Illinois) United States |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | girder bridge |

| Material | Stainless steel, reinforced concrete, and hardwood |

| Total length | 935 feet (285.0 m) |

| Width | 20 feet (6.1 m) |

| Clearance below | 14 feet 6 inches (4.4 m) |

| History | |

| Designer | Frank Gehry |

| Engineering design by | Skidmore, Owings and Merrill |

| Construction end | May 22, 2004 |

| Opened | July 16, 2004 |

| Location | |

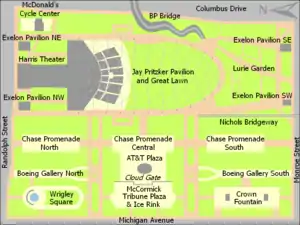

The BP Pedestrian Bridge, or simply BP Bridge, is a girder footbridge in the Loop community area of Chicago, United States. It spans Columbus Drive to connect Maggie Daley Park (formerly, Daley Bicentennial Plaza) with Millennium Park, both parts of the larger Grant Park. Designed by Pritzker Prize-winning architect Frank Gehry and structurally engineered by Skidmore, Owings and Merrill, it opened along with the rest of Millennium Park on July 16, 2004.[1] Gehry had been courted by the city to design the bridge and the neighboring Jay Pritzker Pavilion, and eventually agreed to do so after the Pritzker family funded the Pavilion.[2][3][4]

Named for energy firm BP, which donated $5 million toward its construction, it is the first Gehry-designed bridge to have been completed.[5] BP Bridge is described as snakelike because of its curving form.[6] Designed to bear a heavy load without structural problems caused by its own weight, it has won awards for its use of sheet metal. The bridge is known for its aesthetics, and Gehry's style is seen in its biomorphic allusions and extensive sculptural use of stainless steel plates to express abstraction.

The pedestrian bridge serves as a noise barrier for traffic sounds from Columbus Drive. It is a connecting link between Millennium Park and destinations to the east, such as the nearby lakefront, other parts of Grant Park and a parking garage.[7] BP Bridge uses a concealed box girder design with a concrete base, and its deck is covered by hardwood floor boards.[8] It is designed without handrails, using stainless steel parapets instead. The total length is 935 feet (285 m), with a five percent slope on its inclined surfaces that makes it barrier free and accessible. Although the bridge is closed in winter because ice cannot be safely removed from its wooden walkway, it has received favorable reviews for its design and aesthetics.

Design

Preliminary plans

Since the mid-19th century, Grant Park has been Chicago's "front yard", with Lake Michigan to the east and the Loop to the west. Columbus Drive runs north–south through Grant Park, with Daley Bicentennial Plaza in the northeast corner of the park. West of Columbus Drive, the northwest corner of the park had been Illinois Central rail yards and parking lots until 1997, when it became available for development by the city as Millennium Park. Millennium Park is also north of Monroe Street and the Art Institute, east of Michigan Avenue, and south of Randolph Street.[9] For 2007, Millennium Park trailed only Navy Pier as a Chicago tourist attraction.[10]

In February 1999, the city announced it was negotiating with Frank Gehry to design a proscenium arch and orchestra enclosure for a band shell in the new park, as well as a pedestrian bridge crossing Columbus Drive between Millennium Park and Daley Bicentennial Plaza. The city also sought donors to cover the cost of Gehry's work, which would eventually become Jay Pritzker Pavilion and the BP Pedestrian Bridge.[11][12] At the time, the Chicago Tribune dubbed Gehry "the hottest architect in the universe" in reference to the acclaim for his Guggenheim Museum Bilbao.[13] Millennium Park project manager Edward Uhlir said "Frank is just the cutting edge of the next century of architecture", and noted that no other architect was being sought.[11] Gehry was approached several times by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill architect Adrian Smith on behalf of the city.[3] In April 1999, the city announced that the Pritzker family had donated $15 million to fund Gehry's band shell and an additional nine donors committed a total of $10 million more to the park.[2][14] That same day, Gehry agreed to the design request.[4]

In November 1999, when he unveiled his initial plans for the bridge and band shell, Gehry admitted the bridge's design was underdeveloped because funding for it was not yet committed. Even at this early point, the need for a sound barrier for Columbus Drive traffic noise was recognized, although Gehry indicated this might take the form of a berm, or raised barrier.[15] The need to fund a bridge to span the eight-lane Columbus Drive was evident, but some planning for the park was delayed in anticipation of details on the redesign of Soldier Field.[16] In January 2000, the city announced plans to expand the park to include features that became Cloud Gate, Crown Fountain, the McDonald's Cycle Center, and the BP Pedestrian Bridge.[17] Later that month, Gehry unveiled his next design, which depicted a winding bridge.[18]

While the neighboring Jay Pritzker Pavilion changed relatively little from Gehry's 1999 design when built, the bridge went through several proposed designs.[19] The proposal made in early 2000, which was expected to be executed in 2002, included a bridge that was a mere 170 feet (51.8 m) long and 20 feet (6.1 m) wide.[20] That design was not approved, and Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley's disapproval of Gehry's subsequent design of an 800–900-foot (240–270 m) bridge caused Gehry to come up with ten more designs.[21] The first of these plans was for a Z-shaped bridge that would have run northwest–southeast with western ramps in Millennium Park, leading south, and eastern ramps in the empty north section of Daley Bicentennial Plaza, leading north. It would have required elevators to conform to the Americans with Disabilities Act.[19] This plan was abandoned because it would have segregated the handicapped.[22] Gehry had only designed two bridges previously, both in the mid-1990s (Pferdeturm USTRA Bridge in Hanover, Germany and Financial Times Millennium Bridge in London, United Kingdom) but neither was built.[19]

Final plan

The final design for the bridge was revealed in an exhibit at the Chicago Cultural Center on June 10, 2000.[21] As designed and built, the bridge is 935 feet (285.0 m) long and 20 feet (6.1 m) wide, with a 14-foot-6-inch (4.42 m) Columbus Drive clearance.[23][24] The clearance was designed to slightly exceed the 14-foot (4.3 m) standard set by the United States Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration for urban area interstate bridge clearances, and to allow for additional future layers of pavement below.[25] This height is also greater than the maximum vehicle height of 13 feet 6 inches (4.1 m) set by the Illinois Vehicle Code.[26] According to the Chicago Tribune the width of the "trenchlike" area spanned is approximately 150 feet (46 m),[21] while The New York Times reports the bridge is over ten times longer than Columbus Drive is wide.[27]

BP Bridge begins in Millennium Park between the trellis system over the Jay Pritzker Pavilion's great lawn and the Lurie Garden; the design was changed so that the west ramp coincided with the boardwalk of the Lurie Garden seam.[28][29] The bridge winds its way northward along the eastern edge of Millennium Park before crossing Columbus Drive in a C-shaped curve, above underground parking garage entrances. In Daley Bicentennial Plaza the bridge has an S-shape, then turns east. BP Bridge is designed so that its inclined surfaces have a continuous five percent slope rather than landings and switchback ramps, which provides easy access for the physically challenged.[21][30] The gently sloped ramp eliminates the need for lifts or any of the other common types of ramps (L-shaped, switchback, U-shaped, straight),[31] and helped the park earn the 2005 Barrier-Free America Award for its exemplary barrier-free design.[32]

Gehry had hoped to design the bridge so that it could be constructed without a support column in the center of Columbus Drive. However, Chicago Tribune architecture critic Blair Kamin notes that if he had done so, the bridge might not have been as sleek.[6] Building the bridge without the column would have required load-bearing cantilevers (beams supported only on one side) from structural positions on opposite sides of the street; this would have been expensive and labor-intensive, because it would have required excavating large portions of the parking garages on both sides of the street. Moreover, on the Daley Bicentennial Plaza side, the optimal location for the supporting cantilever would have been at the location of the Monroe Street Garage. Thus, the preferred bridge design was altered to avoid problems related to the underground parking garages.[33]

The bridge is both a connector and a viewing platform for the park.[6] It was designed to link the Historic Michigan Boulevard District and the entire Loop to the west with the Lake Michigan lakefront to the east. It was also designed to be a berm noise barrier blocking noise on the eight-lane Columbus Drive from the Park's outdoor band shell (Jay Pritzker Pavilion), by deflecting traffic sounds upward.[34]

The bridge, which uses steel girders, reinforced concrete abutments and deck slabs, hardwood deck, and a stainless steel veneer, cost between $12.1 and $14.5 million.[34][35][36] It contains large sculptural plates of curvilinear stainless steel instead of more standard flat plates.[1] The bridge's curvilinear design gives it a flowing, natural look, instead of the linear, rigid form of standard bridges. Although its steel girders rest on concrete pylons and most of the bridge is solid concrete, the bridge uses a hollow box girder design to minimize weight, as the ground that supports the bridge covers underground parking garages.[8][37] The concrete base and box girder are flanked by a hollow stainless steel skeleton.[8] Despite its hollow structure, and the fact that it is designed as a concealed beam bridge, the footbridge is built to highway standards and can support a full capacity load of pedestrians.[37] The bridge is designed without standard handrails and uses waist-high parapets as guard rails instead.[6]

Construction

The bridge was built using 22-gauge stainless steel type 316 plates (0.031 inches or 0.79 millimeters thick), with an angel hair finish and a flat interlocking panel process. Stainless steel type 316 is known for its excellent welding characteristics, as well as for its resistance to pitting.[38] According to the Chicago Tribune, the bridge materials used in construction include 2,000 rot-resistant Brazilian hardwood boards for the deck, 115,000 stainless steel screws and 9,800 stainless steel shingle plates.[28][37] According to Architecture Metal Expertise, the bridge has "10,400 stainless steel trapezoidal panels in 17 different shop fabricated configurations [which] involved 1,000 shop hours".[34] The sheet metal work totaled 5,900 field hours over a six-month period.[34] During construction, about 200 shingles were installed per day.[39] The bridge includes two types of structural steel: steel that is 2.0 inches or 5.1 centimetres thick and 20.0 inches or 51 centimetres in diameter for the approaches and box girders for the span.[40]

CATIA software was used to handle the complex geometric layout.[41] To ensure accurate fitting and alignment to the sloping, curving sides of the bridge, 4,400 custom-made convex, concave and radiused cladding panels were fabricated on site by sheet metal contractor Custom Metal Fabricators (CMF). CMF used 57,000 square feet (5,300 m2) of stainless steel sheet to cover the sides, which have a combined perimeter length of 1,728 feet (526.7 m). CMF built special heated enclosures so that work could continue on site through the winter. They designed, fabricated and installed custom type 4 brushed stainless steel parapets serving in the place of handrails on the bridge. CMF earned the 2005 Tom Guilfoy Memorial Architectural Sheet Metal Award, by the California chapter of the Sheet Metal and Air Conditioning Contractors' National Association for the project.[34] In 2005 it received a Merit Award from the National Steel Bridge Alliance, and an Excellence in Structural Engineering award from the Structural Engineers Association of Illinois.[42]

On the day that the two halves of the bridge were joined, each side of Columbus Drive was closed for a 12-hour period and a 360-short-ton (320-long-ton; 330 t) crane was used to install the girders. Before bringing the crane to the location, screw jacks were used to shore up the underground garage roof to hold the crane's weight.[43]

The landscaping surrounding the bridge was redesigned by landscape architect Terry Guen. Honey locusts, ash and maple trees were removed and replaced with three varieties of magnolia and more than two dozen ornamental and canopy trees along the eastern foot of the bridge in Daley Bicentennial Plaza. Other preliminary construction work included setting reinforcing rods for the bridge in the concrete roof deck of the parking garage located under the park.[23]

Use and controversies

Before its official opening, the bridge had a May 22, 2004, private ribbon-cutting ceremony attended by Gehry and Mayor Daley. During the weekend of the ribbon-cutting, Gehry was awarded an honorary degree from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago.[44] The BP Pedestrian Bridge officially opened, along with the rest of Millennium Park, on July 16, 2004.[1][37] It remained unnamed at the ribbon-cutting,[37] but before the July park opening, energy firm BP had paid $5 million for the bridge sponsorship and naming rights.[45]

Timothy Gilfoyle, author of Millennium Park: Creating a Chicago Landmark, notes that a controversy surrounds the "tasteless" corporate naming of several of the Park's features, including the bridge, which was named after an oil company.[46] It is well documented that naming rights were sold for high fees,[47] and Gilfoyle was not the only one who chastised park officials for selling naming rights to the highest bidder. Public interest groups have crusaded against commercialization of Chicago parks.[48] However, many of the donors have a long history of local philanthropy and the funds were essential to providing necessary financing for several features of the park.[45]

After the park opened, some of the bridge's foibles became apparent. The bridge has had to be closed during the winter because freezing conditions make it unsafe.[49] Since the bridge is over an expressway-like trench of Columbus Drive, shoveling the snow onto passing cars is not an option and the Brazilian hardwood would be damaged by rock salt.[50] The city not only mandates that the bridge be swept and washed daily, but also that the parapets be wiped free of fingerprints.[51]

The bridge has also had controversial closures in the summer, which were related to larger park concerns. On September 8, 2005, Toyota Motor Sales USA paid $800,000 to rent the bridge and all but four venues in the park from 6 a.m. to 11 p.m.[52][53] On August 7, 2006, Allstate paid $700,000 to rent the bridge and most of the park for a day.[54][55] The exclusion of commuters who normally walk through the park and tourists lured by its attractions was controversial, though the city said the money raised paid for free public programs in Millennium Park.[52]

Aesthetics

The bridge is noted for its sculptural characteristics and Kamin describes it as a delightful pleasure that was designed to emphasize its artistic elements while de-emphasizing its concrete and steel support system.[6] The New York Times notes that the artist Anish Kapoor's attempts to hide the seams of Cloud Gate were an interesting contrast to Gehry's architectural efforts. Gehry took pride in making the BP Pedestrian Bridge flaunt its seams.[27]

Beginning with Gehry's earliest bridge designs, the bridge was expected to complement the neighboring Pritzker Pavilion.[20] Some have suggested that the bridge and the pavilion are mere extensions of Gehry's work in other cities. For example, according to Gilfoyle, both structures embody Gehry's established asymmetrical style, evoking fluid, continuous motion and sculptural abstraction. They also feature metallic facades and aesthetic curves, but they are said to be more refined, reduced and dynamic than much of his other work.[57]

Since the 1960s, Gehry has made artistic use of scaled animals such as fish and snakes, which first appeared in his architectural designs in the 1980s.[58][59][60] Many references to the bridge describe it as snakelike for its winding path,[6][34][44] and some even refer to the stainless steel plates as scales with discussion of reptilian forms.[19][41] Kamin calls it "a bridge that resembles a giant silver snake, complete with a scaly skin",[6] while Gehry said he thought the bridge looked like a river, but added he might be the only one who thought that.[44]

The way the bridge flows in a continuum of unexpected directions is a break from Gehry's other work and other more traditional urban and architectural forms nearby.[57] Pulitzer Prize-winning architecture critic Kamin gave the bridge four stars (out of a possible four) in his review and admires how "computers have given Gehry unparalleled formal freedom" to design "the complexity of its geometry" and multidimensional curvatures.[6] The bridge provides views of both the Historic Michigan Boulevard District and Lake Michigan in a way that Kamin says makes it a belvedere.[6][61] Kamin also recommends anyone having a bad day to stroll across the bridge, adding, "You won't get where you're going quickly, but you'll feel a whole lot better once you're done."[6]

Credits

- Commissioned by – The City of Chicago[11]

- Architect – Gehry Partners, LLP[62]

- Landscape Architect - Terry Guen Design Associates

- Project manager – US Equities[62]

- Construction manager – URS Construction Services[62]

- Structural engineer – Skidmore, Owings and Merrill[62]

- Mechanical and electrical engineer – McDonough Associates[62]

- Contractor – Walsh Construction[62]

- Subcontractor – Permasteelisa Cladding Technologies Ltd.[63]

- Steel supplier – Littell Steel Company[35]

- Steel construction – Imperial Construction Associates[35]

- Sheet metal contractor – Custom Metal Fabricators Inc.[34]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 "Category: Intensive Industrial/Commercial". Green Roofs for Healthy Cities. 2005. Archived from the original on June 8, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- 1 2 Spielman, Fran (April 28, 1999). "Room for Grant Park to grow". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on December 20, 2014. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- 1 2 Kamin, Blair (April 18, 1999). "A World-Class Designer Turns His Eye To Architecture's First City". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- 1 2 De LaFuente, Della (April 28, 1999). "Architect on board to help build bridge to 21st century". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on December 20, 2014. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ↑ Cohen, Laurie (July 2, 2001). "Band shell cost heads skyward – Millennium Park's new concert venue may top $40 million". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Archived from the original on December 20, 2014. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Kamin, Blair (July 18, 2004). "BP Bridge – **** – Crossing Columbus Drive – Frank Gehry, Los Angeles". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Archived from the original on December 20, 2014. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ↑ Daniel, Caroline (July 20, 2004). "How a steel bean gave Chicago fresh pride". The Financial Times. The Financial Times Ltd. Retrieved July 31, 2008.

- 1 2 3 Gilfoyle, pp. 196–201.

- ↑ Gilfoyle, Timothy J. (August 6, 2006). "Millennium Park". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 12, 2017. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ↑ "Crain's List Largest Tourist Attractions (Sightseeing): Ranked by 2007 attendance". Crain's Chicago Business. August 6, 2008. p. 22.

- 1 2 3 Bey, Lee (February 18, 1999). "Building for future – Modern architect sought for park". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved May 21, 2009.

- ↑ "The City". Daily Herald. Newsbank. February 18, 1999. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ↑ Warren, Ellen and Teresa Wiltz (February 17, 1999). "City Has Designs On Ace Architect For Its Band Shell". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ↑ "Millennium Park Gets Millions". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. April 27, 1999. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ↑ Kamin, Blair (November 4, 1999). "Architect's Band Shell Design Filled With Heavy-Metal Twists". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ↑ Kamin, Blair (November 23, 1999). "Timing Crucial Plotting Grant Park's Future". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ↑ Song, Lisa (January 7, 2000). "City Tweaks Millennium Park Design". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ↑ Donato, Marla (January 28, 2000). "Defiant Architect Back With Revised Grant Park Bridge Design". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Gilfoyle, pp. 239–41.

- 1 2 Kamin, Blair (March 20, 2000). "Lakefront Park Plans To Include Visitors' Bridge". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Kamin, Blair (June 23, 2000). "Gehry's Design: A Bridge Too Far Out?". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ↑ Sharoff, p. 95

- 1 2 Moffett, Nancy (May 26, 2003). "Millennium Park getting a touch of the South". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved May 31, 2008.

- ↑ Frey, Mary Cameron (May 24, 2004). "Our Town's newest bridge". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ↑ "Bridge Technology". United States Department of Transportation – Federal Highway Administration – Infrastructure. July 7, 2006. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved October 2, 2008.

- ↑ "(625 ILCS 5/15‑103) Illinois Vehicle Code". Illinois General Assembly. Archived from the original on January 19, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2009. Note: The code states that vehicle height statewide measured from the under side of the tire to the top of the vehicle, inclusive of load, that shall not exceed 13 feet 6 inches (4.1 m).

- 1 2 Bernstein, Fred A. (July 18, 2004). "Art/Architecture; Big Shoulders, Big Donors, Big Art". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 8, 2008. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- 1 2 Gilfoyle, p. 243.

- ↑ Gilfoyle, pp. 303, 308.

- ↑ "Art & Architecture: BP Bridge". City of Chicago. Archived from the original on May 26, 2008. Retrieved May 31, 2008.

- ↑ "Accessible Housing by Design—Ramps". Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation. August 2008. Archived from the original on May 13, 2008. Retrieved August 5, 2008.

- ↑ Deyer, Joshua (July 2005). "Chicago's New Class Act". PN. Paralyzed Veterans of America. Archived from the original on April 13, 2019. Retrieved May 31, 2008.

- ↑ Gilfoyle, p. 200.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Form And Function Come Together To Create A Pedestrian Bridge For Chicago: Millennium Park BP Pedestrian Bridge, Chicago, Ill". Architectural Metal Expertise. SMILMCF. Archived from the original on May 9, 2012. Retrieved May 31, 2008.

- 1 2 3 BP Pedestrian Bridge at Structurae Retrieved on July 25, 2008.

- ↑ Herrmann, Andrew (July 15, 2004). "Sun-Times Insight". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Janega, James (May 22, 2004). "Curvy bridge bends all the rules – With its whimsical, wavy design, the new Millennium Park bridge has Chicagoans likening it to a skateboard, a snake—even a spaceship". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Archived from the original on December 20, 2014. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ↑ "Grade Data Sheet 316 316L 316H" (PDF). Atlas Specialty Metals. May 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 22, 2008. Retrieved June 5, 2009.

- ↑ Sharoff, p. 105

- ↑ Sharoff, p. 100

- 1 2 Sharoff, p. 103

- ↑ "Millennium Park – BP Pedestrian Bridge". Skidmore, Owings and Merrill. Archived from the original on May 22, 2009. Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- ↑ Sharoff, p. 109

- 1 2 3 Nance, Kevin (May 23, 2005). "Snakelike walkway by Gehry dedicated at Millennium Park". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- 1 2 Smith, Sid (July 15, 2004). "Sponsors put money where their names are". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- ↑ Gilfoyle, p. 345.

- ↑ Kinzer, Stephen (July 13, 2004). "Letter from Chicago; A Prized Project, a Mayor and Persistent Criticism". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 8, 2012. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ↑ Spielman, Fran (September 2, 2004). "Corporate logos in parks? Daley thinks it's 'fantastic' // Says companies deserve it if they foot the bill". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- ↑ Nance, Kevin (December 16, 2005). "Museum seeks $63 mil. more: Art Institute needs donations to build addition, bridge". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ↑ Mihalopoulos, Dan and Hal Dardick (January 7, 2005). "Park spares the salt and closes the bridge". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ↑ Spielman, Fran (December 16, 2005). "New amenities for Millennium Park?: Company proposes baby strollers, Disney training for workers". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on May 4, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- 1 2 Ahmed-Ullah, Noreen S. (September 9, 2005). "No Walk In The Park – Toyota VIPs receive Millennium Park 's red-carpet treatment; everyone else told to just keep on going". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014. Retrieved July 26, 2008.

- ↑ Dardick, Hal (May 6, 2005). "This Sept. 8, No Bean For You – Unless you're a Toyota dealer. In that case, feel free to frolic because the carmaker paid $800,000 to own the park for the day". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014. Retrieved July 26, 2008.

- ↑ Herrmann, Andrew (May 4, 2006). "Allstate pays $200,000 to book Millennium Park for one day". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Archived from the original on December 17, 2014. Retrieved July 26, 2008.

- ↑ The four venues in Millennium Park that were not rented by Toyota were Wrigley Square, Lurie Garden, the McDonald's Cycle Center and Crown Fountain. Allstate acquired the visitation rights to Pritzker Pavilion, BP Bridge, Lurie Garden and the Chase Promenades, and only had exclusive access to Cloud Gate after 4 p.m.

- ↑ As of 2009, the recently constructed Legacy Tower blocks the view of the bridge and Millennium Park from Sears Tower at least partially.

- 1 2 Gilfoyle, pp. 229–231.

- ↑ Jencks, Charles (2002). The new paradigm in architecture: the language of post-modernism. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-300-09513-5.

- ↑ Waters, John Kevin (2003). Blobitecture: Waveform Architecture and Digital Design. p. 161. ISBN 978-1-59253-000-7.

- ↑ Feuerstein, Günther (2001). Biomorphic Architecture: Menschen- und Tiergestalten in der Architektur. p. 131. ISBN 978-3-930698-87-5.

- ↑ Gilfoyle, p. 272.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Facts and Dimensions of BP Bridge". City of Chicago. Archived from the original on May 3, 2008. Retrieved May 31, 2008.

- ↑ "BP Bridge at Millennium Park". Radius Track Corporation. Archived from the original on February 15, 2019. Retrieved September 28, 2011.

References

- Gilfoyle, Timothy J. (2006). Millennium Park: Creating a Chicago Landmark. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-29349-3.

- Sharoff, Robert (2004). Better than Perfect: The Making of Chicago's Millennium Park. Walsh Construction Company.

.jpg.webp)